44 Become a submariner

WHAT IT IS Life beneath the ocean waves

WHY YOU WON’T DO IT Aside from the claustrophobia, it’s a killer for your social life

Anyone who has read Jules Verne’s Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea or watched Das Boot is unlikely to feel entirely confident about rushing off to become a submariner. Nonetheless, there still seem to be plenty of hardy souls who hear the calling to lock themselves in a small tin can and live on the ocean floor – maybe you’re one of them?

Today, submarines have a wide variety of uses ranging from tourism through oil exploration to oceanographic study. However, the most common way to become a submariner is still by joining your country’s navy.

They’ll put you through a vigorous programme of training, testing you to make sure you’re physically, psychologically and temperamentally suited to the job: if you’ve got even a whiff of claustrophobia about you, it’ll be found out and you’ll be restricted to surface operations. Try to remember it’s for your own good – you’re going to be in a small space that you can’t leave for weeks or even months at a time. To give you an idea of what you might face, a Royal Navy Trafalgar Class boat (submarines are always ‘boats’, never ‘ships’) is only 85 metres (280 ft) long, 10 metres (33 ft) high and 10 metres (33 ft) wide, and it has to function as home and workplace for 130 men for six months at a stretch. It all sounds a lot less jolly than, say, living with the Beatles on their famous Yellow Submarine.

Fortunately, seasickness tends not to be too much of a problem – you might think that bumping along at the bottom of the sea would guarantee nausea, but in fact the water down there is considerably calmer than it is on the surface.

A submarine requires all sorts of specialist professions on board, from engineers to cooks. It is vital that everyone works in harmony at all times, and because of the peculiar demands upon them, naval submariners are almost always volunteers, even in wartime. In virtually every navy, submariners are male only. This can lead to a certain level of tension and, dare it be said, ‘frustration’ among crew. The average age of a submariner is 21. Relationships are, not surprisingly, difficult to keep going underwater. Marriage breakdown is not uncommon among submariners.

You’ll also have to cope with boredom, although you should at least have plenty of opportunity to catch that film you missed at the cinema or finally finish that book (ideally not The Hunt for Red October). You will probably work a regimented shift pattern of six hours on and six hours off. Four meals are served a day, with the crew usually managing to eat at two of the sittings. Due to the absence of space for exercise, many submariners complain of putting on weight during a voyage.

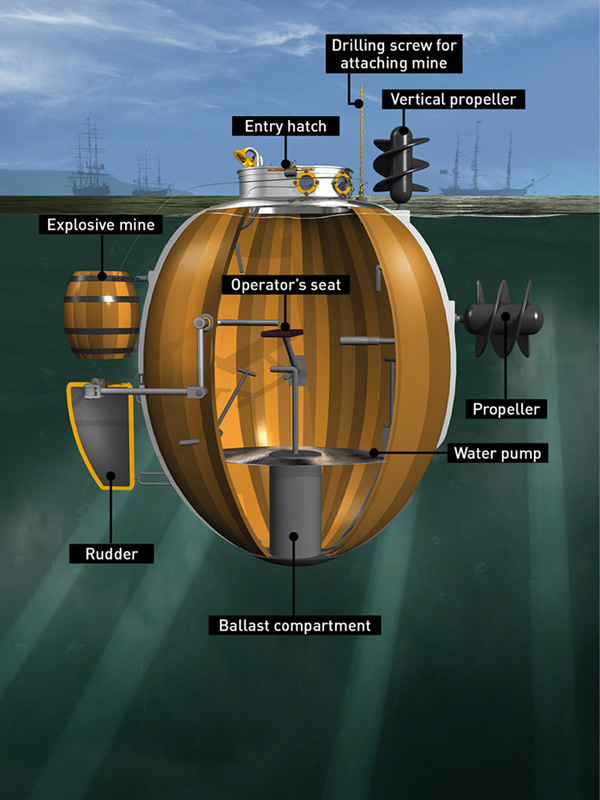

BARREL OF FUN Today’s submarines are luxurious compared to their predecessors. This cutaway shows the interior of the Turtle, the world’s first military submersible. Built in Connecticut in 1775, it was a one-man vessel intended for use against British warships in the Revolutionary War, but proved ineffective.

To save space, bunks are normally stacked in threes. Your privacy (what there is of it) is preserved by a curtain, and aside from your bunk, you might only have a shelf or locker to call your own. If you’re unlucky you may even have to ‘hot bunk’ – grabbing whichever bunk comes free at the shift changeover. What’s more, fresh water is at a premium so you may have to go for several days, or even weeks, without showering.

For security reasons, communication with the outside world is minimal, although satellite technology makes it possible to keep in contact with vessels virtually anywhere. A captain will often have to decide whether a submariner should be told some bad news while he is powerless to do anything about it.

While modern submarines have every safety provision imaginable, disasters can still happen: in 2000, for instance, the Russian sub K-141 Kursk sunk in the Barents Sea with the loss of all 118 hands. If something goes really wrong down there, you are in trouble. So if you’re determined to travel in a sub, why not take an easier option than joining the navy? If you have deep pockets, you could fork out for a trip to see the wreck of the Titanic in a sub. Prices start at around US$60,000 per person.

TIN OF SARDINES Crew members relax in their bunks aboard the Ohio-class nuclear submarine USS Alabama – the red light provides safe levels of constant illumination without disrupting sleep. It might not be spacious, but it’s a lot more comfortable than conditions aboard the early submersible Turtle (shown earlier), used against British ships in the War of Independence.