Chapter Five

THE WENLOCK EDGE PROJECT

MY SMALL FARM, which stretches up to the edge of the woods which clothe the top of Wenlock Edge, was originally carved out of the open fields of the mediaeval village community. A relic of the original enclosure was a long narrow paddock bordering a stream, which was called the ‘The Slang’, a name for one of the strips into which the open fields were divided. The communal lands were equitably laid out to enable each of the villagers to have his share of the different types of land which the parish comprised: cornfields, upland pastures and lowland meadows. In certain lights the strip-pattern can be clearly discerned on my largest field.

In laying out Highwood Hill, as I called the farm after one of the woods above it, I originally designated five small pasture fields and two orchards, in one of which I kept a flock of free-range hens, as the cash-component. These were eventually taken over by a community.

My self-sufficiency efforts were concentrated on the ‘bailey’, which is a tongue of land of about one acre, beside and behind the cottage, and the adjacent depression which the archaeologist surmised had been a monastic fish-pond. While this was mainly occupied by a plastic tunnel for winter vegetables, I divided the ‘bailey’ into a garden of herbs and perennial vegetables, which meant digging up the lawn; a blackcurrant plantation; a tiny orchard of apples, pears and damsons; and a large vegetable garden. The small orchard, about one-eighth of an acre, was to become my model forest garden.

The small garden of herbs and perennial vegetables lay literally outside the kitchen door, on the south-west side of the cottage – an ideal position. It was a suntrap, protected from north and east winds, and the person preparing a meal could nip out, just before serving it, to pick a handful of fragrant greenery, fresh from the soil, to add to salad, soup or stew. We found many uses for the plants that grew there. Lovage, that statuesque plant which can grow over eight feet tall, can be used as a piquant substitute for celery, to which it is related. Lemon-balm, eau-de-cologne mint and peppermint can give an original tang to fruit-salads. Sweet cicely can reduce the tartness of stewed gooseberries or blackcurrant pie. Good King Henry, a wild form of spinach, also known as ‘Lincolnshire asparagus’, can be added to stews, as can the young leaves of dwarf comfrey – one of the few herbs that continue to put out leaves during the winter. The leaves of sorrel, with their mild lemon flavour, and wild garlic, with its not-somild reminder of its cultivated cousin, make an interesting substitute for lettuce in salads.

From the first, these exciting plants inspired experiment. I realised that perennial herbs, with their deep roots tapping the minerals in the subsoil, could make an invaluable contribution to nutrition over and above their curative and prophylactic powers. I tried passing them through the juiceextractor together with our home-grown apples, pears and blackcurrants, to produce delicious non-alcoholic ‘liqueurs’. Peppermint, eau-de-cologne mint and other herbs, added to apples, plums, damsons and dried apricots – the whole pressed through a colander after stewing – produced uncommon jams, ‘cheeses’ and chutneys. Moreover, honey from our own hives, the inhabitants of which were particularly attracted to the blueish flowers of balm and comfrey, added yet another dimension of nourishment and flavour. A range of ‘Herb and Honey Products’, which I developed, included Rejuce, a herbal slimming drink, and attracted the attention of a director of a newly formed health-food manufacturing company, which I was invited to join. Unfortunately the time did not seem ripe for its activities and after a short period, it folded up.

But I continued to work – or rather not-work – our herb-garden. The plants, I found, could look after themselves very nicely, thank you. All they needed was a dressing of straw or compost in the winter, and every spring they faithfully re-appeared, sending out fresh shoots and leaves for months on end. Pests and diseases were conspicuous by their absence.

My creative faculties were also attracted to another traditional aspect of these fascinating plants: their reputed ability to extend their vigour, health, disease-resistance and pest-resistance to neighbouring plants. At the far end of the ‘bailey’ Harry and Victor Tipton laid out a large garden of conventional vegetables. Among these I planted rows of applemint, borage and other herbs – and the vegetables seemed to like them. They grew well, even though the herbs rapidly became rather too rampant. I saw cabbages struggling manfully through mini-jungles of borage. Borage, though an annual, is an avid self-seeder and, in its second year, the vegetable garden seemed to shimmer in the electric-blue haze of its ever-present flowers.

Another experiment I made in the vegetable garden was a system of ‘organic irrigation’. I got a local engineer to make an adjustable valve that could be fitted to the pipe from which the spring emerged beside the cottage. To this was attached a length of alkathene piping extending to the far end of the vegetable garden, which was on a gentle slope. Taps were fitted at intervals of about twenty yards. Channels were then dug by mattock from top to bottom of the vegetable garden, on both sides, and between the rows of vegetables. In order to water a double-row of vegetables, all that was necessary was to turn on the nearest tap and direct the water to the vegetables by mattock, smoothing and hardening the channel bottoms. Water was also switched from channel to channel by means of small dams of compost or manure. That was where the ‘organic’ element came in, as particles of compost or manure were washed down the channels, to which was added liquid seaweed. The whole area was thus, in time, thoroughly fertilised.

Fig. 5 Fan-trained plum tree with blackcurrant bush

The task of clearing the channels of loose mud and mole-hills and constructing new channels was greatly facilitated by the force of water gushing from the taps. The mattock was used as a multi-purpose tool: while digging channels, one also hoed, weeded and earthed up the vegetables. The whole system was beautifully simple, easy and cheap.

However, in comparing the garden of conventional vegetables with the garden of herbs and perennial vegetables, it was obvious which demanded the least work. In growing annual plants one can’t avoid the arduous and fiddlesome chores of digging, raking, preparing seed-beds, sowing, transplanting, thinning out, hoeing, weeding, watering and fertilising. But the herbs and perennial vegetables, once established, needed little or no watering or fertilising, because their deep roots drew up water and minerals from the subsoil, for the benefit of themselves and each other, and they did not even need hoeing and weeding, as they quickly spread over the whole surface of the soil, suppressing all competitors, while their intricate tangle of roots maintained a porous soil-structure. All they did need was periodical thinning-out, to prevent them from encroaching on each other, but, as they constituted an important part of our daily diet, a fair proportion of the thinnings found its way into the kitchen.

Pondering on the contrast between the two gardens, it came to me that, if one could devise an integrated system of land-use consisting mainly of perennial plants – fruit and nut trees and bushes together with perennial vegetables and herbs – as well as a diet based on this mix, the task of achieving self-sufficiency would be vastly simplified. This is how I discovered agroforestry.

The decisive event which enabled me to work out a demonstration of how agroforestry could be applied in the conditions of western, largely urban, civilisation, where in general only small plots of land are available for self-sufficiency enthusiasts, was the advent of Garnet Jones. Living in the village at the bottom of the hill, he is a Celt of magnificent physique, who comes from an old yeoman family in the wilds of Mid-Wales. While his whole nature is steeped in traditional country lore and his roots are deep in the soil, he has an alert and lively mind, receptive to new ideas. A true yeoman, he can turn his hand to a wide variety of practical tasks, and, having also worked on the railway, he shows something akin to genius as an engineer. He is of the stuff of the countrymen, who, torn from the soil, pioneered the Industrial Revolution in the Ironbridge Gorge area of Shropshire and elsewhere in Britain. His enthusiastic participation in the Wenlock Edge Project has been intensely stimulating, while his muscle-power and brain-power have been invaluable. The creation of the project has been a partnership between us.

The project now comprises a number of sectors:

1. The main Forest Garden, literally the centrepiece.

2. The Ante(i) Forest Garden (AFG), so called because it comes before (ante) the main forest garden and contains plants requiring full sunlight and/or acid soil, which are therefore antagonistic (anti) to forest garden conditions.

3. The Homegarden, an area about twenty metres square immediately adjacent to the house, containing fruit, vegetables and herbs, which, for some mysterious reason, is exceptionally productive. So-called because ‘homegarden’ is the term by which most tropical forest gardens are known.

4. Where It All Began, a strip of economic plants surrounding an old Improved Fertility pear outside the back door – a tiny microcosm of the whole project.

5. The Patio Garden, a small assembly of plants in tubs, designed to demonstrate that even towndwellers with only small paved yards can enjoy some of the benefits of the Forest Garden.

6. The Wild-life Sanctuary, a prehistoric packhorse track, possibly a stone axe trading route, which constitutes a very deep cutting or ‘hollow-way’ along the garden’s northern boundary. As it contains some magnificent old trees, it can be regarded as a strip of ancient, natural forest. It is left completely undisturbed and is scheduled as a Prime Site of Conservation Interest.

7. The Osier Coppice, cut once a year for basketry.

8. The Arboretum, containing specimen trees of special interest, including Shagbark Hicory (Carya ovata), which has been described as ‘the most valuable nut-producing species in the USA’; Silver Maple (Acer saccharinum); Arolla Pine (Pinus cembra); Maidenhair Tree (Ginkgo biloba) and Dawn Redwood (Metasequoia glyptostroboides), two ‘living fossils,’ typical of the vegetation that created the coal measures 100 million years ago; Antarctic Beech (Nothofagus antarctica), probably the most southern tree in the world; Red-twigged Lime (Tilia platyphylios rubra); Red Oak (Quercus rubra), an American species noted for its brilliant autumn colouring; Service Tree (Sorbus domestica), which bears small edible fruit known as ‘chequerberries‘, German Walnut (Juglans regia, var. Buccaneer), an early-fruiting variety, and White Mulberry (Morus alba), which produces both edible fruit and leaves which are used for feeding silkworms.

9. The Circle-dancing Area, a small open space surrounding the Massingham Oak, where dancing takes place during seasonal festivals. It is overlooked by the Tree House, built part-way up a living ash, which constitutes an irresistible attraction for children. Also nearby is the Ecological House, a small cabin built very expertly by Garnet (who also built the Tree House), which is lit by a wind-generator and contains a small collection of interesting examples of craftwork from several parts of the world.

Fig. 6 Circle-dancing round the oak tree, with the Chinese goddess of mercy

10. The Winter Garden, a number of beds and a mound, mostly unshaded, designed for winter vegetables.

11. Forest Garden No. 2, a small multi-storey plantation surrounding the Kagawa Plum.

12. The Bog Garden, a plantation of reeds and other plants requiring damp conditions, irrigated by Garnet’s waterwheel in the Packhorse Track.

The main Forest Garden has contained over 100 species and varieties of plant in its very limited area – about that of a large town garden – but some have not been fully adapted to the conditions and have died off. At present the number of species and varieties is at least seventy and others are being added every year. Like the natural forest, it is a largely self-regulating, developing ecosystem that requires minimal maintenance.

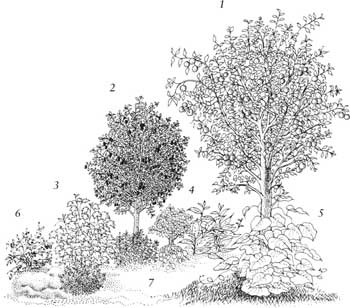

Fig. 7 Cross-section of temperate forest garden, showing seven ‘storeys’:

1. Canopy – largest fruit trees. 2. Lower fruit trees – dwarfing fruit trees. 3. Shrubs – currants and berries. 4. Herbaceacous – herbs such as comfrey. 5. Vertical-climbing berries and vines. 6. Soil surface – dewberries and creeping herbs. 7. Rhizosphere – vegetables and root layer.

The ‘storeys’ comprise:

‘Canopy’: standard or half-standard fruit trees;

‘Low-tree layer’: fruit and nut trees on dwarfing rootstocks and bamboo;

‘Shrub layer’: currant and gooseberry bushes and Rosa rugosa;

‘Herbaceous layer’: herbs and perennial vegetables;

‘Ground-cover layer’: creeping plants such as rubus species;

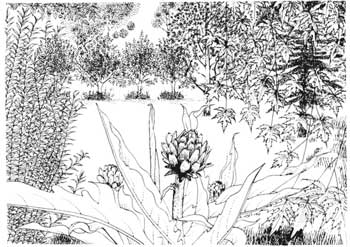

Fig. 8 An artist’s impression of the forest garden

‘Rhizosphere’: shade-tolerant and winter root-plants;

‘Vertical layer’: climbing berries, nasturtiums, runner beans and vines, trained up trees, over fences and over a shed.

The system is self-perpetuating, because almost all the plants are perennial or active self-seeders, such as borage and cress; self-fertilising, because deep-rooting trees, bushes and herbs draw upon minerals in the subsoil and make them available to their neighbours, and because the system includes edible legumes which inject nitrogen into the soil and mineral-rich plants such as buckwheat, which inject calcium; self-watering, because deep-rooting plants tap the spring-veins in the subsoil, even at times of drought, and pump up water for the benefit of the whole system; self-mulching and self-weed-suppressing, because rapidly spreading herbs, such as mints and balm, soon cover all the ground between the trees and bushes and thus create a permanent ‘living mulch’; self-pollinating because the trees are carefully selected to be mutually compatible or self-fertile, and because the flowering herbs attract pollinating insects; self-healing, because the scheme includes a number of aromatic herbs, which undoubtedly deter pests and disease-germs and exhale healing radiations; resistant to pests and disease, because of the aromatic plants, and because any complex comprising a wide spectrum of different plants does not allow the build-up of epidemics such as affects monocultures.

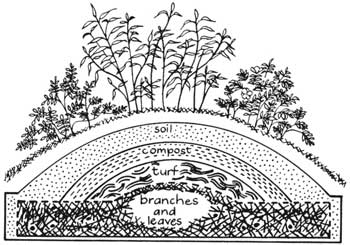

Fig. 9 Rose-mound showing construction layers

This forest garden model, which could be reproduced even in smaller areas, and in town gardens and wastelands, could, when well established, enable a family to enjoy a considerable degree of self-sufficiency for some seven months in the year, in the very best foods for building up positive health.

The Ante(i) Forest Garden, with its annual vegetables, sun-loving herbs and strawberries, as well as some fruit trees and bushes, is conveniently situated immediately outside the back door – one minute’s walk from the kitchen. And, in approaching it, the first sight that meets one’s eyes is Where it All Began: my first experiment in companion planting or plant symbiosis. It consists of a small Improved Fertility pear closely surrounded by black, white and red currants and herbs. I can never remember the little pear-tree or the currants failing to give bumper crops, a sign that they seem to enjoy each others’ company as well as that of the herbs. A tiny area, yet intensely productive, year after year.

Just inside the gate is another mini-plantation: the Patio Garden, designed to demonstrate to the town dweller that it is possible to have a forest garden even if one has no garden at all, but only a paved yard. It comprises plants in tubs and trained up a trellis. Most of the plants are lime-haters, so they wouldn’t thrive in ordinary soil anyhow. Growing in ericacious (or ‘heath-soil’) compost and peat, they include four blueberries and a witch-hazel. There is also a dwarf ‘Lilliput’ apple and an ornamental gooseberry as well as the – to me – inevitable herbs. Two dwarf roses enhance the gaiety of the scene.

Fig. 10 Bouché-Thomas hedge

Nearby are two further ‘anti’ beds, containing plants that would not enjoy forest garden conditions, because, in their native state, they grow in treeless bogs, heaths and grassland. The bog-garden comprises peat spread over a plastic sheet to restrict drainage; it contains cranberries and other vaccinium species as well as a flowering rush and Siberian iris. The sun-loving herb garden comprises typical downland plants, such as thyme, marjoram, yarrow and rue, growing in a light soil, also mixed with peat.

Another device of interest to the town dweller with very restricted space is the mound-garden. Originating in China, like so many other down-to-earth practical ideas, mound planting has been taken up with enthusiasm in Germany, where it is called ‘Hugelkultur’. Unlike the raised bed system, which involves double-digging, you start the mound by making a trench about one-foot deep. This is piled up with woody material, such as small branches, hedge cuttings and prunings, to make a firm but highly porous core, enabling air, water and sunshine to circulate freely. This framework is then covered with sods, placed grass-side downwards, followed by a layer of compost, the whole being topped with soil. Plants are grown both on the top and sides of the mound, so that the space-saving advantages are obvious. It should be said, however, that the mounds gradually sink, so that they have to be periodically renewed. The AFG contains three such mounds.

Fig. 11 The Packhorse Trail

Fig. 12 Arch of Gaia

Along the north boundary of the AFG is a ‘Bouché-Thomas’ hedge, consisting of apple trees planted diagonally so that they grow into each other and so create a rigid fence. I first learned about this system in an article by the gardener of Caldey Island monastery, off South Wales, where the system was formerly used to provide windbreaks for asparagus.

Approached through the wrought-iron ‘Arch of Gaia‘, created by my next-door neighbour in the valley, who lived with his wife and a multitude of dogs and cats by the packhorse bridge, the arboretum contains a wide variety of trees, as well as the ecological house ‘Cookery Nook’ with its wind-generator and a waterwheel, which will be described in more detail in later chapters.

As with my animals, so I have developed warm personal relationships with many of my trees. Until I came into intimate daily contact with a large concourse of young trees, with a wide diversity of shapes, colours, sizes, habits and uses, I never realised how fascinatingly individual trees can be. In early spring it is a daily thrill to watch the ways in which different trees spring into new life. Some of my most valued trees – which are not necessarily the most valuable – have been named after people to whom they have been dedicated; people, some famous, some obscure, who have influenced my life and thought.

The practice of tree dedication began when a couple, David and Stella Griffiths of Middlesbrough, who showed an interest in my agroforestry experiments, expressed a wish to plant four trees in memory of their parents. They asked me to choose the trees which I considered most suitable, and I bought from a local nursery four wild cherries – a species that will for ever be associated with Shropshire through A E Housman’s lines:

Loveliest of trees, the cherry now

Is hung with bloom along the bough,

And stands about the woodland ride

Wearing white for Eastertide.

The cherries were planted in the AFG as the arboretum had not them been started.

Pride of place in the arboretum must go to the English oak commemorating H.J. Massingham, that eloquent defender of the English rural tradition to whom I owe so much.

Other trees and their dedicatees include:

Atlas Cedar: Richard St. Barbe Baker and his great scheme for Sahara reclamation;

Southern Beech (Nothofagus antartica): Edward Adrian Wilson, naturalist, doctor and antarctic explorer, who died with Scott;

Western Red Cedar (the totem pole tree): Chief Seathl, whose ecological-ethical philosophy is relevant to some of the profoundest problems of today;

Shagbark Hickory: Tsikatsitsiakwa (known as ‘Katsi’), a Mohawk maiden who established a Permaculture group in New York State;

Shropshire Damson: Mary Webb, the novelist, a Shropshire damsel;

Sugar Maple: Helen Nearing, whose classic on self-sufficiency Living the Good Life was written in collaboration with her husband Scott;

Red Lime: Blanche Cazalis, a charming Parisian artist who introduced me to Tisane de Tilleul, lime-flower tea;

Chestnut Marron de Lyon: Claude Monet, my most beloved of landscape painters;

Scots Pine: Marjory Kennedy-Fraser, collector and arranger of Hebridean folk-songs;

Fir (Abies grandis): Leos Janacek, the composer who put his beloved Moravian forests into his opera The Cunning Little Vixen;

Arolla Pine: Rainer Maria Rilke, the German-Czech poet to whose tower-retreat in Switzerland I made a pilgrimage during my last holiday abroad;

Walnut ‘Buccaneer’ (a German hybrid): Johann Wolfgang Goethe, universal genius, whose pioneer botanical work revealed the Urpflanze, the primal plant;

Japanese Red Cedar: Toyohiko Kagawa, another universal genius who originated Forest Farming;

Apple Court Pendu Plat (said to go back to Roman times): Virgil, epic poet who also created an agricultural masterpiece, the Georgics;

Apple ‘Flower of Kent’: said to be the tree that inspired Isaac Newton’s Theory of Gravity;

Monkey Puzzle (Araucaria araucana – from Chile): Victor Jara, the Chilean folk-singer martyred in 1973;

Himalayan Whitebeam: Murlidhar Devidas Amte, whose heroic struggles on behalf of leprosy sufferers, of Indian aborigines and their rainforest home have been of truly Himalayan proportions.