Chapter Eleven

AGROFORESTRY

AGAINST WORLD WANT

THE BEST ANSWERS to Third World problems can generally be found in the Third World itself. Its people have vast reserves of skill, resourcefulness, creativity, inventiveness, energy, survival techniques and will to win, of which most Westerners seem largely unaware. But since many Western aid schemes, notably the ‘Green Revolution’ and a number of big dams, have proved costly failures, an increasing number of relief workers and agronomists have, from the mid-1970s onwards, been taking a close scientific interest in indigenous methods. When asked to solve the problems of a particular valley, far-sighted administrators have learnt to turn, not to Western mechanical and chemical know-how, but to systems practised in the next valley.

Of course this does not mean that Western expertise in many fields has no role to play in tackling the Third World’s colossal and multifarious problems. In the realm of forestry one name must stand out, that of a man of enormous energy and all-encompassing vision, who foreshadowed and inspired the present worldwide Green movement, and even shared Gandhi’s convictions linking a post-industrial society with lasting peace. This man was Richard St. Barbe Baker, who, as a young forester in 1922, founded the Men of the Trees in Kenya, a country that is now playing a leading role in many departments of tree-planting and which holds the headquarters of the International Council for Research in Agroforestry.

In his book My Life My Trees St. Barbe describes the devastation of the forests in the Kenya highlands caused by nomadic herdsmen, land-hungry white farmers and logging contractors. The young forester’s response was to demarcate a wide area and get it gazetted as a forest reserve. With the co-operation of a man who was to be his lifelong friend and colleague, the Kikuyu chief Josiah Njonjo, St. Barbe had thousands of indigenous trees planted between rows of corn and yams – an agroforestry system. At the same time he started Kenya’s first large tree nursery, planting olives in conjunction with Mutarakwa cedars, an association found in the natural forest. Thus, from the first, as he admitted, St. Barbe took advantage of the local tradition of mixed cropping.

Later St. Barbe became responsible for the sustainable development of mahogany rainforests in Nigeria, where he observed another example of plant symbiosis.

Each mahogany is surrounded by numerous trees belonging to other families, amongst which is that important family of Leguminosae – the soil improvers. These I have observed to be good nurse trees for the mahoganies. The more important species of mahogany require the services of a succession of nurse trees throughout their life to bring them to perfection. Some of these provide just sufficient competition to coax the young sapling upwards. Others do their work in secret under the surface of the soil, interlacing the roots, a sort of symbiosis, like the mycelium, which starts as an independent web-like growth, surrounds the sheath of plant rootlets and prepares food that can be assimilated by the growing trees.

In the 1950s and 1960s St. Barbe undertook two extensive expeditions through and round the Sahara, and put forward a breath-taking plan for the reclamation of the world’s largest desert by progressive tree-planting.

In their foreword to his book Sahara Conquest John Hutchings and Knut H. Scharnhorst write:

This outstanding book introduces us – in a bold yet down to earth manner – to a new way of thinking. Against the sombre background of a world-wide population explosion with its serious food problems the author calls for immediate, concerted efforts to restore to the world in general and to the Sahara in particular, the potential productiveness of abused and abandoned land. Man must stop defying the laws governing him in his relations to Nature, especially the basic law of balances. Instead, the nations must adopt and adapt the principles of ecology in dealing with human problems. This goes – in the author’s opinion – not only for re-afforestation but, logically, also for reduction of animal husbandry to adequate proportions. Never has ecology had a more objective and articulate spokesman than in Richard St. Barbe Baker, who also more than any other Westerner loves Africa and her people.

Co-operation on a large, international scale, such as Mr. Baker invites in the case of the Sahara, would go far to change the political climate of the nations. Just as Mr. Baker’s reclamation plan envisages the creation of micro-climates in the Sahara, that will eventually coalesce into a beneficial climate over the whole area, so will the total African venture in itself act like a micro-climate, which will gradually expand to the whole of our fractious and contending planet.

What is here presented is not just an abstract scheme proposed by a poet dreamer (though the author is indeed a poet). It is the plan of a practical forester, who has spent his life in the pursuit and study of his subject from every technical point of view, who has travelled the world over and who has seen for himself the cancerous condition in which the surface of our planet finds itself…

Mr. Baker is an acknowledged world authority, who can point to huge areas reclaimed or saved by his inspiration and who here assures us that with up to date knowledge and modern techniques a million square miles of the Sahara can now be reclaimed. In a sorely perplexed world, this book is a sweeping Charter of Sanity that points the way to sound prosperity, wellbeing and peace, not only for the Uniting States of the Sahara, but for all of us.

In fact St. Barbe did not put forward a detailed programme but encouraged the Saharan states which he visited to proceed with schemes best suited to their individual talents, policies and resources. He was particularly impressed by large-scale desert colonisation schemes being pioneered by Egypt, one of which involved 5-acre family orange groves with leguminous crops such as peanuts and cowpeas growing beneath the trees.

While water for some of the projects was provided by irrigation channels from the Nile, in other cases wells were sunk, some of depths as great as 3,600 feet. Ancient wells, some going back to Roman and pre-Roman times, were discovered and opened up. There is said to be an underground sea the size of France beneath the Sahara. This could doubtless be made available for irrigation by modern oil-drilling techniques.

The remains of ancient civilisations have been found near the centre of the Sahara. Their water-supplies must have been assured by the presence of forests, but when these were cut down and regeneration made impossible by browsing animals, the water-table, maintained by the trees’ roots, would have sunk to great depths.

St. Barbe’s vision of a Green Belt round the Sahara was revived at an exhibition in London in October 1989, sponsored by a number of relief agencies. The exhibition did not envisage an endeavour to plant a continuous shelterbelt round the desert’s entire perimeter, but a mosaic of protective zones, comprising forests of drought-resistant trees and crops, which would eventually merge.

Innumerable forms of land-use practised in Africa, Asia and Latin America, whether traditional or extemporised, have agroforestry characteristics. It is being increasingly recognised that symbiotic systems, involving the integration of trees with other crop-plants, constitute a vast and complex subject of study, which contains the seeds of a comprehensive new-old technology for meeting all basic human physical needs.

Paul Harrison in The Greening of Africa praises ‘the resourcefulness and energy of Africa’s farmers’ and adds:

There is here a tremendous untapped potential for rapid innovation… Africa’s peasants, in my experience, are among the most inventive and adaptable in the world. They have to be, because they are dealing with the most varied and unpredictable environment in the world. They are always open to new varieties, even new crops, that can make the best of their limited resources… British anthropologist Paul Richards has shown that traditional farmers, untouched by conventional development projects, select and breed their own improved varieties, carefully adapted to the needs of their location… In no other continent is there such a diversity of farming methods… They have developed dozens of ways of moulding the soil, planting sometimes in ridges and mounds in wet areas to improve drainage, sometimes in furrows and hollows in dry areas, to collect scarce water.

Patterns of intercropping are even more diverse. In northern Nigeria as many as 156 separate crop combinations have been observed.

In south-eastern Nigeria, to meet the challenge of one of Africa’s most densely-populated areas, a sophisticated system of forest gardening has been developed. ‘Compound farms’, some very small, are established in the immediate vicinity of homesteads. A very wide diversity of trees, bushes and other crop plants are grown, designed to meet all the basic needs of the farmers and their families: fruits; vegetables (including perennial tree vegetables); timber for building, staking and fencing; fuel; fertilisers; leaf wrappers; medicines; fibres for ropes, stuffing mattresses and thatching; calabashes for containers; charcoal; wood for tool handles; snake repellents; gums; dyes; kitchen utensils; spices and water purifiers. Many of the trees are used for multiple purposes. So sophisticated and complex is the ‘architecture’ of some of the gardens that as many as nine storeys have been counted: from high emergent coconut and oil palms to medium-sized trees such as breadfruit and pear and lower trees such as mango, orange and lime. On a still lower level grow papaya and bananas, with pepper bushes occupying the shrub layer. Maize and vegetables constitute the herbaceous layer, while melons, peanuts and other horizontally spreading plants cover the ground, and root vegetables occupy the rhizosphere. The vertical dimension is formed by yam vines trained up trees. The genetic diversity of the plants makes the gardens important as germplasm banks, supplying replacements for genes lost as a result of forest destruction. The system, which is believed to have originated 1,000 years ago, and so has been tried and tested over the centuries, could serve as a model for many other parts of Africa – and the world. People who have evolved and are prepared to maintain such a complicated system must be determined to survive at all costs!

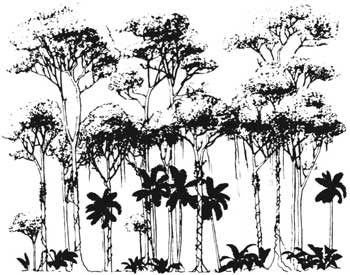

Fig. 22 Chagga forest garden (illustration © IIED)

Another forest garden system with more commercial implications has been developed by the Chagga people of Tanzania amid glorious scenery on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro. The special sophistication of this system lies in the network of skilfully aligned irrigation channels designed to make full use of the melting snows. The network, which is very complicated, is managed co-operatively by all the smallholders and is so arranged that each one gets his fair share.

The Chaggas were originally members of a number of different tribes who, over a century ago, moved into the dense montane rain forest on the lower slopes of the great mountain, which covers an area of more than 3,000 square kilometres, and rises to 5,895 metres above sea level. When the first missionaries reported seeing a snow-capped mountain just south of the Equator, their superiors refused to believe them. The pioneer Chagga settlers refrained from felling the larger and more valuable trees in the forest, but planted bananas and other fruit and vegetables in their shade. Now the individual plots, which average 0.68 hectares in size, each one maintaining a family of about ten people, generally have a sevenstorey structure. At the top are the tall timber trees, including teak, of the natural forest. In their shade grow shorter trees, providing fuel and fodder. Lower still is the fruit storey, mainly comprising bananas but including other fruit and fodder trees as well. Next comes the coffee layer, which also includes some medicinal plants. The herbaceous layer comprises vegetables such as beans, cabbages, cowpeas, onions and tomatoes, as well as maize, and also young saplings of natural species which have been allowed to survive. The rhizosphere is occupied by potatoes, taro and other root crops, while a vertical dimension is created by yams which are trained up trees.

Over a hundred different species are grown, supplying most of the families’ personal needs throughout the year, as well as bananas and coffee which are sold. The Chagga area contributes more than fifty per cent of Tanzania’s coffee output and therefore makes an important contribution to the country’s GNP. The most valuable products are the choice timber trees.

An intensely interesting feature of the system, which deserves scientific research, is that a number of plants are grown for their symbiotic qualities, in repelling nematodes and other pests. Chemicals are seldom used.

Great expertise is shown in managing the system, as the smallholders have an intimate knowledge of all the plants and their ecological requirements. For example, when the time is ripe, the canopy is opened out to facilitate the fruiting of the coffee bushes, while each banana clump is pruned to ensure that it has three to five pseudostems of different ages, thus making for continuous harvesting. Young timber trees are grown in close proximity to other plants to encourage straight stems with few branches. The wide diversity of very carefully chosen plants is an insurance against both epidemics and crop failures. If one crop fails, another is likely to be a resounding success.

Fig. 23 Profile of tropical rainforest showing storeys (illustration ©IIED)

Tenure of each forest garden, or vihamba, is hereditary, and is based on a very strong conviction that a close link exists between a person’s ancestors and the soil. Traditionally the land was divided only between the deceased owner’s sons but now the daughters are included. Each family, also has another plot, called a kishamba, held by annual tenancy, in the plains. These plots are mainly used for annual crops, though a few trees are grown in them, mainly for fuel.

This combination of upland and lowland husbandry reminds me of a system which I found operating in the Val d’Anniviers in Switzerland. There, dairy farming was the main occupation in the mountains while each family also had a share in a vineyard in the Rhone Valley. At the beginning of spring all the men marched down to the valley to work in the vineyards, carrying their hoes and headed by a fife band, leaving the women to look after the cattle.

Another very interesting forest garden system in a mountainous rainforest area is that of Maninjau, an extinct volcano on the island of Sumatra. The setting is dramatic in the extreme: steep mountainsides clothed with remnants of primaeval forest sloping down to a volcanic lake, subject to dangerous landslides and violent storms.

Fig. 24 Mangrove tree

Just as the inhabitants of Saxon England left patches of virgin forest undisturbed close to their villages, to supply them with timber, herbs and other necessities, so the inhabitants of Maninjau build their villages round tongues of natural rainforest. Above the 900-metre line is a large Staterun forest reserve, from which the villagers are forbidden to collect wood and rattans (creepers). In the buffer-zone between the forest and villages are the majority of the forest gardens, though smaller homegardens surround many of the houses. In these the villagers plant their most valued fruit trees, for security reasons. The villagers also cultivate rice in permanent irrigated fields at the bottom of the slopes and by the lakeside. The land in general is owned communally by the clan.

The forest gardens are densely planted with a wide diversity of trees and other deep-rooting perennials, to guard against landslides and erosion. Annual vegetables and maize are grown beneath the trees and also in the ricefields, between harvests. All the gardens are dominated by six specially favoured trees and bushes: durian, cinnamon, nutmeg, coffee, Pterospermum javanicum, a large timber tree commonly grown in association with durian, and Toona sinensis, a medium-sized timber tree regarded as particularly suitable as a shade-tree for nutmeg and coffee. At the head of all these trees in local preference must come the durian, whose large, spiny fruits are loved by millions of people in Southeast Asia but detested by others for their sewage-like smell. Appropriately enough, durian rinds are used for manuring coffee bushes, which, together with nutmeg trees, are often grown beneath the shade of the durian trees. Among other fruit grown or collected from the wild are bananas, papayas, guavas, mulberries, mangoes and mangosteens. Many bamboos are grown both for their edible shoots and for construction purposes. The peasants have an intimate knowledge of their plants’ ecological and cultural requirements. Almost all the work is done by family labour; very little machinery and no chemical fertilisers are used. The whole system is highly stable and sustainable, and yet readily adaptable to changing needs and economic conditions. To counter the unreliability and fluctuations of market demands for the cash crops – coffee, cinnamon and nutmeg – the peasants maintain a solid nucleus of subsistence crops, so they are never obliged to go short of necessities.

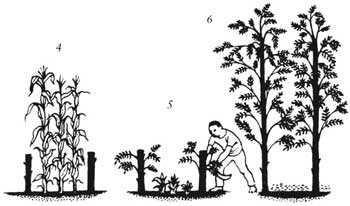

Fig. 25 Alley-cropping with leguminous trees like Leucaena. In the first year the seedlings are planted with the crops (1,2), then allowed to shoot up in the dry season (3).

In subsequent years, the trees are pruned for wood, fodder and mulch while crops are growing (4,5), and allowed their head again in the dry season (6).

As in the case of other forest garden systems, the wide diversity of home-bred and semi-wild species provides a gene bank which is potentially of great value for plant-breeders in other parts of the world, who find many sources of supply dried up by the destruction of the natural forests.

That the rainforest peoples should be allowed to survive and develop in their own indigenous ways, aided and supported by legitimate, constructive forms of Western technology, mostly in its ‘intermediate’ or ‘alternative’ forms, is of importance to us all. One American psychologist, Jean Liedloff, has even created a system of psychology and child care which she calls The Continuum Concept, based on several years’ intimate contact with the Ye’cuana, a tribe of Amazonian Indians. Briefly, the Continuum Concept describes the security derived from the extension of maternal protectiveness and stimulus, which has been the main biological means responsible for the evolution of the higher animals and human beings, into the sphere of communal living. The autonomous village community, which is the highest unit of Ye’cuana society, is the solid, supportive matrix within which almost all activity takes place. In an emergency, any member of the community can rely on the wholehearted aid and support of the rest. Social responsibility rather than competitiveness characterises the whole of Ye’cuana life, and, as everyone, from earliest childhood, is expected to act altruistically without compulsion, unbroken harmony is the general rule.

The forest community is so deeply embedded in its environment that it conforms to the laws of its ecosystem as implicitly as do the animals and plants. Peter Bunyard in The Colombian Amazon writes:

The dynamic of the forest and the interchange of matter between one species and another, including that of life-force, provides the Indians with a ready model of their own existence within the community of the maloca (communal house). Hence the local economy both within the community and with neighbouring communities relies heavily on the principle of exchange and reciprocity both within themselves as human beings and with nature… Gerardo Reichel-Dolmatoff has good evidence that the rituals and beliefs of the Indians of the eastern part of the Colombian Amazon are based solidly on their conscious experience of how the ecosystem works and is an attempt to reflect that natural functioning within their own cosmologies.

A dominant feature of all true, unspoilt forest people is a respect for the environment, amounting sometimes to religious reverence, based on intimate, inherited understanding of its flora and fauna, its processes and rhythms. The Yanomani of the Amazon rainforest, the largest unacculturated tribe in the Americas, have an amazingly varied diet and pharmacopoeia derived from both wild and cultivated sources. While they collect more than 500 different wild plants, including many fruits, they also clear small areas in the forest, called chagras, in which they create temporary but highly diversified forest gardens. These, after a short time, they allow to become overgrown, in order to restore the fertility of the thin rainforest soils, while they move on to clear other patches. The forest gardens thus become constituents of the forest ecosystem, which is thereby enriched, becoming even more productive of economically valuable plants.

The Ye’cuana village community apportions its cultivating and foraging area into a number of distinct zones. Immediately round the village or maloca lies the forest garden, in which they plant their favourite fruittrees, such as peach palm, papaya, pear, mango, lemon and maraca, a kind of cacao. Next comes the nearby forest, from which the people reckon to collect some 170 different species of wild plant, not only for food but also for timber, fuel, medicines, utensils and dyes. In this and the more distant forested areas are found sites destined for chagras as well as rastrojos, which are abandoned forest gardens in various stages of regeneration, which are still visited for their surviving fruit-trees. There are also various wetland areas, including cananguchales, permanently or seasonally flooded, which contain a tree called canangucho, which is much prized for its fruit.

The Baka of the Central African rainforest divide their lives into settled periods, when they do some cultivation, and a nomadic phase which begins with the onset of the rainy season and the fruiting of the wild mango tree. Their camps comprise small igloo-shaped huts woven by the women from wild saplings and thatched with large leaves.

One of the supreme benefits that the human race could gain from the rainforest, which in many countries is being so ruthlessly destroyed, is an immense expansion and diversification of its diet. At present the vast majority of the world’s population suffer from inadequate nutrition. There is the malnutrition of poverty and the malnutrition of affluence. While hundreds of millions of people eat too little, tens of millions eat too much of the wrong foods. Comparatively few people consume sufficient quantities of the two basic essentials for all-round, lasting, positive health: raw green leaves and fresh fruit. Moreover, if one is to be sure of obtaining all the desirable vitamins, enzymes, minerals and other nutrients, a widely varied diet is needed. For this reason, a far-ranging programme of nutritional research should be undertaken into the foods consumed by the Yanomani and other forest people who are experts on the environment. At the same time there are numerous neglected food plants in the comparatively species-poor temperate regions. Also we should not forget that every variety of common fruits such as the apple, plum, pear, raspberry and gooseberry has a different biochemical constitution, and therefore contains different trace-elements. As a very limited number of varieties are obtainable in the shops, and most of these have been sprayed and grown with chemical fertilisers, everyone with a garden of any size should endeavour to grow a few of the non-commercial varieties, which are generally superior in flavour to shop fruit. This is why I grow a wide diversity of fruit and nut trees, including uncommon ones, such as sorbus species and the azerole, an edible hawthorn.

Forest gardening, in the sense of finding uses for and attempting to control the growth of wild plants, is undoubtedly the oldest form of land-use in the world. One of the newest is alley-cropping, a form of agroforestry developed during the 1970s and 1980s by B. T. Kang, an Indonesian soil scientist, and his colleagues at the International Institute of Tropical Agriculture, Ibadan, Nigeria. It was an attempt to find answers to two problems: soil erosion on sloping ground and the acidification and impoverishment of the soil, which are the long-range results of using chemical fertilisers. The system which Kang and his colleagues came up with involved the growing of cereals and vegetable crops in narrow strips between hedgerows of leguminous trees. The trees, with their deep roots, prevent erosion, and with their nitrogen-fixing ability fertilise the crops. They are regularly and heavily pruned to prevent them from shading the crops, the prunings being used as mulch to suppress weeds, as stakes or firewood, or as fodder to be fed to livestock. Hedgerows along the contours of sloping ground accumulate loose soil and in time a series of terraces develops.

The trees must be fast-growing, and among those that have proved most satisfactory are Leucaena leucocephala, a native of southern Mexico, otherwise known as ipil-ipil or subabul, Calliandra calothyrsus, a small Central American tree with showy flowers resembling crimson powderpuffs, and Sesbania Grandiflora, a very valuable multi-purpose tree from Asia with large white or wine-red flowers that have been described as ‘vegetable humming-birds’! Philistine though it may seem, these flowers, which are rich in sugar, are sold in many Asian markets for food – they are said to taste like mushrooms. Sesbania pods are eaten like runner-beans and the seeds, among the richest in protein of all legumes, are dried and eaten like soya beans. The leaves, which are also rich in protein as well as vitamins and minerals, are eaten as spinach. In traditional agroforestry the tree is used as a support for pepper and vanilla vines.

Bill Mollison told me that Sesbania roots are so powerful that he has seen the tree used for reclaiming rock-hard lateritic soils. Leucaena, another tree with an aggressive taproot that can shatter rocks and which is also amazingly fast-growing, has, in numerous field trials, proved the most satisfactory hedgerow tree for alley-cropping. Crop-yields are not reduced but increased in its neighbourhood. It was a favourite tree of the Maya and Zapotec civilisations of Mexico and Central American, in whose area traditional forest gardens, which doubtless owe their origin to those civilisations, are still found.

Following the successful Nigerian field trials, alley-cropping has spread to other parts of Africa, Indonesia, the Philippines, India and Sri Lanka.

Leguminous plants should be an essential constituent of all agroforestry/permaculture schemes in every habitable part of the world, because of their value as companion plants, giving fertility to their neighbours. The fruits and seeds of many leguminous plants are sources of the first-class protein in which many Third World diets are deficient. It is true that some pulses contain toxins, but reliable methods have been developed over the centuries of detoxifying them. These include boiling them and throwing away the water, and also various forms of fermentation practised in the Far East which have resulted in products, well known in Western health-food stores, such as tofu, tamari, soya milk and soya cheese. In fact, soya beans have been among the main sources of protein for thousands of years in China, Japan and Korea, areas where livestock farming is far less widespread than in the West.

As many leguminous plants are fast-growing, they can provide a regular source of fuel and biomass-energy. One of the most heartrending human tragedies in many parts of the arid tropics is the long and gruelling journeys that millions of women have to take, week in week out, to fetch firewood from ever-receding and dwindling patches of woodland. In parts of the Himalayas women have been known to fall to their death out of sheer exhaustion. But leguminous trees exist that can flourish in the most arid and even heavily salinated soils, as well as in rock-crevices on mountainsides with no visible soil. So there is no reason why leguminous trees should not be grown in abundance in all deprived areas, to provide fuel for cooking, lighting and heating, thus releasing women from the chore of firewood-gathering and enabling them to use their talents and energies in more creative ways: bringing up their children and practising the crafts in which many of them excel.

In order fully to understand agroforestry/permaculture at its best, as illustrated by the tropical forest garden systems I have described, it is essential to appreciate that it involves skilled craftsmanship – and more. The task of creating balanced relationships, rhythms and patterns of growth demands intuitive, aesthetic qualities, comparable to those that lie behind the exquisite artefacts – textiles, pottery, metalwork, carvings – produced in many countries of the Third World.

A tropical rainforest is a supreme and infinitely varied work of art, but, with a touch of human genius, it can be converted into a forest garden system, even more beautiful and vastly more productive. That is why it is not enough merely to campaign for the preservation of the rainforest. It is a compound resource of potentially enormous value to humankind as a whole, if developed – not devastated – in a wise, constructive, sustainable way. Its vast diversity of vegetation, up to now so inadequately studied by science, could be used as a source of new and nourishing foods, of timber for building and crafts, of fibres and dyes for textiles, of medicines, of biomass for energy, of gums, resins and plastics, to meet almost all human needs, above all the basic soul-need of beauty.

Wagner in his operas strove to achieve a Gesamtkunstwerk, a total work of art. A forest garden, replete with fruit and foliage, blooms, birds and insects, mammals and fungi, fascinating scents and sounds, can be a work of art comparable to any of humankind’s highest cultural attainments.

The new but also age-old technology involved constitutes a safe, sustainable, non-polluting and above all profoundly practical answer to the technology developed since the Industrial Revolution which, despite the many benefits conferred, is now inflicting ever greater and more unacceptable damage on the environment. The new technology has very deep roots in the hereditary manual skills, which, above all in the Far East, have enabled workers to adapt to the stringent demands of the most advanced and intricate forms of ‘hi-tech’. This new technology must be developed so that it can help to lead humankind into a safer, kinder, calmer and more peaceful post-industrial age.