23

Across the Water and Into the Trees

‘“Gentlemen,” the red-tabbed Army officer said dramatically pointing to his watch, “I have to tell you that at this moment, British, Canadian and American paratroopers are dropping into Normandy.” It took a few seconds before the full impact of this statement penetrated. Then there were cheers and yells. Pilots got up from their wooden chairs waving their arms about and slapping each other on the back. For them it was a champagne moment and they erupted.’

Briefing to Typhoon pilots of No. 245 Squadron, RAF, 0030 hours, 6 June 1944.1

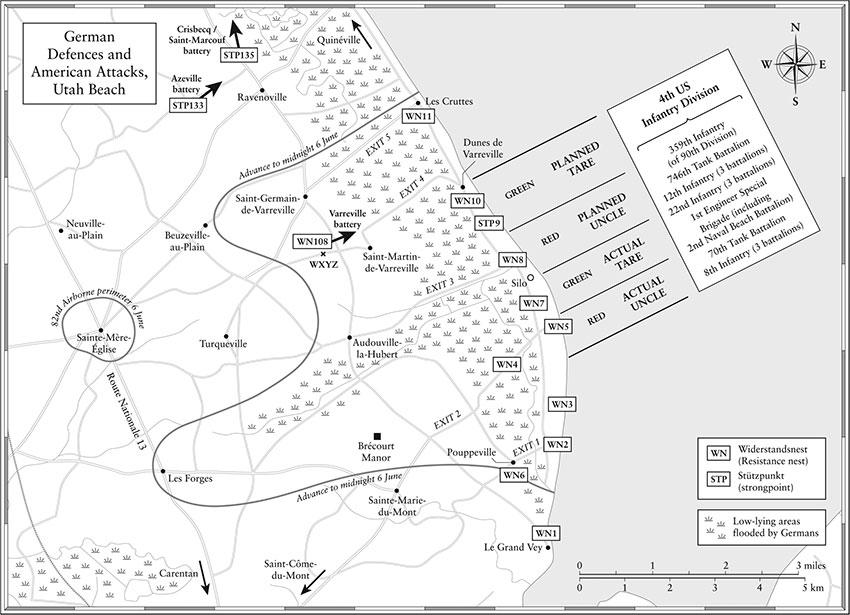

The General’s field telephone rang. Erich Marcks limped over to his desk, his artificial leg creaking; Major Hayn, the intelligence officer, remembered that ‘as he listened, the general’s whole body seemed to stiffen’. In his château overlooking Saint-Lô, his brief birthday celebration over, General Marcks had put off leaving for Rennes. Originally planning to travel in company of Major von der Heydte, the latter had appeared earlier but departed back to his own headquarters. The phone call was not to convey birthday wishes, nor from any units in the Cotentin, but from Generalmajor Richter of the 716th Infantry Division, over in Caen: ‘Paratroopers have landed east of the Orne. The area seems to be around Bréville and Ranville, along the northern fringe of the Bavent Forest.’ Hayn recalled, ‘this struck us like lightning – the corps headquarters soon resembled a disturbed beehive as priority messages were sent in all directions.’2 Marcks – who had anticipated such a move in his kriegsspiel – immediately telephoned Max Pemsel, chief of staff of Dollmann’s Seventh Army, who put the Seventh Army on invasion alert. The time was 0115 hours.

The miscreants were the British 6th Airborne Division, who had deployed by parachute and glider to protect the invasion’s eastern flank. We have seen how its commander, Major General Richard ‘Windy’ Gale, devised Operation Tonga, to insert his men based around two coup de main operations, and the cutting of four bridges over the River Dives. These tactical missions overshadowed the importance of the divisional task – the 3rd and 5th Parachute and 6th Air Landing Brigades were to hold the high ground east of the River Dives and Caen, and prevent the Wehrmacht from slamming into the left flank of Overlord before the seaborne assault troops arrived.

In all, some 5,300 British and Canadian troops of Gale’s division were to be transported by two RAF groups, Nos. 38 and 46, who – not possessing enough aircraft for a single lift – broke down their tasks into two waves. Tonga was dedicated to the main objectives, with the 6th Airborne’s pathfinders deploying at the same time as Howard’s glider men. It would involve 264 transport aircraft conveying 4,512 paratroopers and 1,315 containers of equipment to Normandy. Additionally, ninety-eight gliders left southern England, of which seventy-four were released, though only fifty-two reached their correct landing zones. The second operation, ‘Mallard’, would follow twenty hours later, in the evening of 6 June, enabling RAF pilots to fly two missions. Mallard would deliver heavy equipment, such as Tetrarch light tanks, jeeps, trailers and anti-tank guns, in 216 Horsa and thirty Hamilcar gliders.

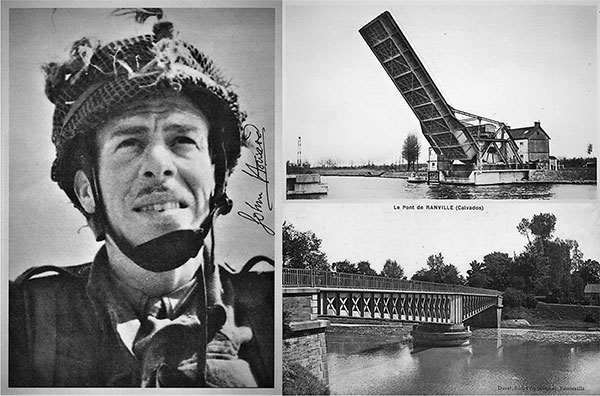

The fine details of seizing the Pegasus and Horsa bridges (respectively, over the Caen Canal and Orne river at Bénouville), as well as the gun battery at Merville, had been thrashed out amid conditions of utmost secrecy at Syrencote House, Figheldean, a Georgian pile on the edge of Salisbury Plain. During training, secrecy had demanded that every reference to Normandy be disguised, so on maps and in staff papers, the Orne was code-named ‘Prague’ and the canal ‘Portugal’. Once the operation was under way, to save time encoding locations for radio transmissions, ‘Prague’ became ‘Cricket’ and the canal ‘Rugger’.

The end result was 181 men of Major John Howard’s ‘D’ Company of the 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry, with two platoons borrowed from ‘B’ Company, thirty Royal Engineers from the 249th (Airborne) Field Company, and medics – and just over 650 men of Lieutenant Colonel Terrence Otway’s 9th Parachute Battalion, plus supporting arms – crouched in their gliders and troop carriers on the runways of RAF Tarrant Rushton in Dorset, and Harwell and Broadwell in Oxfordshire.

Four minutes before 2300 hours on 5 June they felt a distinctive lurch forward, as their aircraft started rolling down the concrete strips towards France. If the Ox and Bucks failed at Bénouville, the 7th Parachute Battalion were to drop in Mae West life jackets with dinghies and paddle into battle. Apart from their commanders – themselves mostly in their late twenties – few had seen previous action. Like their US colleagues of the 101st, Normandy was to be the 6th Airborne’s first brush with the Wehrmacht.

Hunched over his battered wireless set in a captured pillbox, Corporal Edward Tappenden with his headphones was oblivious to all else. Battling with the static, he was concentrating on sending three words to the outside world. ‘Ham and jam; ham and jam; jam and bloody jam,’ he repeated endlessly. Tappenden was announcing the success of Operation Deadstick, Howard’s mission to capture the two bridges near Bénouville. The force had been carried in six Horsa gliders, twenty-eight men apiece, towed across the Channel by Halifax bombers. With perfect navigation and piloting skill, five of the gliders landed on time and on target within yards of each other – three to Pegasus, two to Horsa. Howard’s glider was skilfully placed within a few feet of the canal bridge by Staff Sergeant Jim Wallwork, the London dandy who had volunteered for the Territorials in 1939 to cover himself with ‘medals, free beer and adoring females’.

The German guards initially assumed it was one of the bombers then hitting Caen, downed by flak. After a fierce ten-minute gun battle the bridge was captured, the action over by 0035, a full six hours before the beach landings, and within ninety minutes of having left Tarrant Rushton. Len Buckley, with the 7th Parachute Battalion – the backup force – landed after Howard’s men and ran over to help them. ‘They had obviously had quite a fire-fight,’ he reminisced. ‘We passed an armoured half-track on fire. Hit by a PIAT, the vehicle was exploding all over the place, as its ammunition cooked off.3 Some Germans were charging through the field towards us. I stood up to return fire and I took a bullet which glanced off the butt of my Sten, but passed right through my elbow. If it wasn’t for the Sten, I would have got it in the chest. I was lucky.’4

One of D-Day’s first actions was carried out by Major John Howard (1912–99) (left), who commanded 181 men based in ‘D’ Company of the 2nd Oxfordshire and Buckinghamshire Light Infantry. In Operation Deadstick, men in three of his gliders landed near Bénouville and captured the drawbridge that spanned the Caen Canal (top right). At the same moment, soldiers in two more Horsas seized the nearby swing bridge over the River Orne at Ranville (bottom right). Code-named Rugger and Cricket, they were defended against counter-attacks and afterwards renamed Pegasus and Horsa. (Author’s collection)

Responding to several reports coming in from dazed subordinates, at 0200 hours Hauptmann Eberhard Wagemann, duty officer in Saint-Pierre-sur-Dives, had put the 21st Panzer Division on invasion alert (ready to move in less than ninety minutes).5 Shortly afterwards, patrolling towards Bénouville and Ranville, one of his men, Feldwebel Rainer Hartmetz, a veteran of the Ostfront, encountered ‘one of our half-tracks with an anti-tank gun, riddled with bullets and smeared with blood, and dead paratroopers hanging by their chutes on trees, telegraph poles and chimneys’.6 This was the same half-track seen by Len Buckley, and was actually a self-propelled gun, leading a column of four other armoured vehicles from the anti-tank battalion of the 716th Infantry Division, which had been sent to investigate. (To lightly-armed airborne troops, any tracked vehicle clattering around in the dark armed with a large gun was reported as a tank, and often described as such in British memoirs.)

It had been hit by Sergeant Charles ‘Wagger’ Thornton with his only round of PIAT ammunition, the rest of the ammunition having been lost in the drop.7 The remaining vehicles, unnerved by their encounter with an unseen enemy, had pulled back. The exploding armoured vehicle had emerged at the crossroads (today a roundabout) outside the Bénouville mairie, in front of which lies the commune’s war memorial to the fallen of 1914–18. Shells removed the top of the obelisk during the night-time battle, and today, the severed, pockmarked monument stands in tribute to airborne soldiers and, later, commandos who passed that way.

Meanwhile, Howard’s sixth glider missed its rendezvous at the swing bridge spanning the Orne river, code-named ‘Horsa’. Its occupants became disoriented during the descent, landed by a likely looking structure and captured it, only to find they were miles away from their real objective. As one of the German guards took a bullet, his finger tightened on the trigger and in his death throes he released a round which struck Sergeant Raymond ‘Titch’ Raynor, whom we met earlier training with John Howard. The wounded Raynor thus gained his reputation of being the only British soldier to be shot on D-Day by a dead German.8

During the initial Pegasus Bridge action, platoon commander Den Brotheridge was shot – almost certainly the first British soldier felled by gunfire in Overlord, dying later of his wounds. Undeterred, Howard ordered Corporal Tappenden to send the code words ‘Ham and jam’, indicating that both bridges had been captured – along with the adjacent café, where the bridge sentries Helmut Römer, Erwin Sauer and Wilhelm Furtner had relaxed between sentry duties. They had seen the first glider and ‘at first thought it was a crippled bomber. We wondered whether to take a look at it, or wake our sergeant. Before we knew it, a bunch of about ten wild-looking men were charging at us with guns. We ran.’ Römer was soon rounded up, but remembered that many of the guards who were ‘Poles and other foreign conscripts’ simply melted into the night. The café proprietor, Georges Gondrée, and his family thus became the first French civilians to be liberated, and their establishment – renamed the Pegasus Bridge Café – has acted as a magnet to visitors ever since.9

Gondrée provided some light relief when he dug up his vegetable patch and produced ninety bottles of his finest champagne, artfully hidden from the Germans. Howard observed later that ‘it was remarkable how many of my men developed injuries which required their presence at the café, then an aid post, in order to be treated with Gondrée’s champagne’.10 More amusement arrived when the local area commander, Major Hans Schmidt, was captured when his Mercedes cabriolet staff car ran into one of Howard’s roadblocks. That Schmidt had raced back from an evening of excess with his French girlfriend in Ranville was obvious: the car contained wine, lipstick, food and lingerie. Schmidt demanded to be shot as he had let down his Führer. He was – but only with morphine, to silence his ranting.11

The Pegasus Bridge Café is these days presided over by Arlette Gondrée, who is old enough to remember le bruit du bois casser (the sound of breaking wood) as the gliders landed, and being offered her first chocolate by one of Howard’s camouflaged troopers – who to her seemed like frightening aliens from another planet. This was Lance Corporal Albert Gregory, Royal Army Medical Corps, flying in Howard’s third glider. He had treated the first wounded in a hedgerow before moving them to the safety of the café: ‘I remember a small French girl, ashen-faced and scared to hell. I reached into my tunic and gave her my bar of chocolate, but still she did not smile.’12 A Memorial Pegasus museum opened in June 2000 on the appropriately named avenue du Major Howard, and when Pegasus Bridge (which also starred as itself in The Longest Day) had to be replaced with a newer model, it was decided to relocate the original structure in the grounds of the museum.

Amongst the twenty BBC war reporters who had learned their trade on Exercise Spartan the previous year and deployed on the eve of D-Day were Guy Byam, waiting to jump with the 6th Airborne, and Chester Wilmot (later the author of the authoritative The Struggle for Europe) with its glider-borne contingent. Their vivid despatches, sent back to Broadcasting House on primitive Bakelite discs, were in the best traditions of radio reportage, and transmitted from 6 June onwards after the nine o’clock news in War Report. ‘I am jumping last but one of my stick. In the crowded fuselage all you see in the pale light of an orange bulb is the man standing next to you,’ intoned Guy Byam – destined to die on a bombing raid over Berlin the following February.

Flak – the word is passed from man to man. The machine starts to rock and jump. We’re over the coast now and the run has started – one minute – thirty seconds. Red light – green light, and out. And then the ground comes up to meet me. I can’t be sure where I am – and overhead hundreds of parachutes and containers are coming down. The whole sky is a fantastic chimera of lights and flak, one plane gets hit and disintegrates wholesale in the sky, sprinkling a myriad of burning pieces all over.13

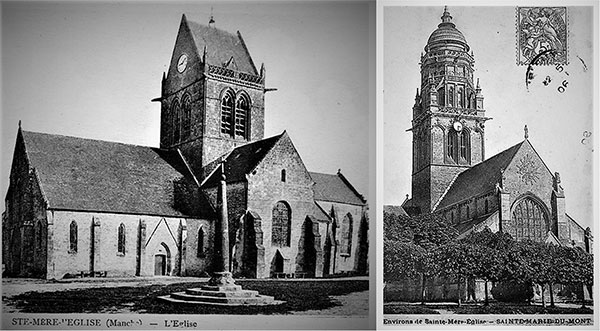

Meanwhile, the Americans had started to pour out of their aeroplanes over the Cotentin. The vicinity of Sainte-Mère-Église, astride the Route Nationale 13, was the objective for many of the 82nd, but few expected – or desired – to land slap in the centre of the garrison town, held by around two hundred men of Oberst Ernst Hermann’s 30th Flak-Regiment. Corporal Earl McClung hailed from Washington State, where he had been born on the Colville Indian Reservation; he was three-eighths Native American and proud of his ancestry. A 101st Paratrooper with ‘E’ Company of the 506th Parachute Infantry under Dick Winters, as he glanced up at his twenty-eight-foot camouflaged silken canopy, suspending him by the same number of thin chords, he noticed his sixty-pound kitbag was pulling him towards a town where a fire was burning – Sainte-Mère-Église, a long way from his scheduled drop zone. He came down on a roof near the church. McClung recalled, ‘It was pretty hectic for the first few seconds. Two Germans were running toward me. I had jumped with my M1 assembled and in my hands: it was no contest – they were only a few feet away and I took care of those guys. I went on by, headed through the graveyard and out of town, and linked up with the 505th of the 82nd. I fought with them for the next nine days.’14 A similar experience befell Charles A. ‘Gus’ Liapes, of Wallingford, Connecticut, with the 506th Parachute Infantry, who came down in a heap in a field. ‘Enemy soldiers came charging across with fixed bayonets. I cut and hacked at my harness in a frantic effort to get out of the way. They were almost on top of me when I got my Tommy gun and fired into them.’15

With the 91st Luftlande Division scattered and leaderless, its operations officer tried to make sense of the situation. As paratroops had been reported in Sainte-Mère-Église, he ordered the 1057th Grenadier-Regiment to seize control of the Merderet river crossings – unknown to him, also an objective of the US 82nd Airborne, who had two drop zones beyond. The 1057th’s Grenadiers took over the Manoir de la Fière on the east bank, but in their hurry, deployed without artillery or armoured support – which would have swung the battle in their favour immediately.

Encountering them at around 0400 hours, troops of the First Battalion of the 505th Parachute Infantry had struck out towards La Fière bridge, two miles west of town. Although the Merderet was narrow at this point, its banks had been deliberately flooded, creating a mile-wide swamp, over which the small stone bridge threaded its way like a causeway. This inundated region of marsh was where many heavily laden 507th and 508th paratroopers landed – well beyond their drop zones further west. Much equipment was sucked into the mire and an estimated 150 airborne soldiers were drowned by their waterlogged chutes and clothing.

The 82nd Airborne’s advance on the bridge was slowed by frequent encounters with roving German troops, and an initial attempt to rush the crossing failed due to alert machine-gunners. It took the day for the 505th just to winkle out their opponents from the Manoir, but American numbers swelled as the eastern embankments overlooking the Merderet became natural assembly points for paratroopers trying to reach their drop zones on the far side.

The bridges at La Fière and further south at Chef-du-Pont rapidly became viciously contested ground. Opposite La Fière, glider troops reached the churchyard at Cauquigny from the west and held off German counter-attacks until ejected in the afternoon by obsolete French tanks, captured in 1940 and operated by the 100th Panzer-Ersatz- und Ausbildungs-Abteilung (Tank Replacement and Training Battalion).

This unit’s full title reveals it was never meant to be a combat formation but used for driving, formation and gunnery training. Its three companies were led by Major Bardtenschlager, headquartered in the Château de Franquetot – soon to be used by J. Lawton Collins as his command post – in the centre of the Cotentin. Bardtenschlager, a wealthy cavalryman whose family ran a well-known publishing business, commanded thirty-two requisitioned French tanks, mostly Hotchkiss models from the 1930s, but some older Renaults which dated back to 1917. None were remotely capable of intimidating, let alone defeating, the Parachute Infantry, and all would be swiftly disabled whenever encountered in the coming hours.

Three of these thinly armoured, two-man little vehicles moved onto the La Fière bridge and were immediately knocked out by bazooka rounds from the paratroopers defending the eastern bank. Bardtenschlager himself, along with the commander of his No. 1 Company, Oberleutnant Weber, would die later in the day. At Chef-du-Pont, troops led personally by Brigadier General Jim Gavin could make no headway and returned to reinforce La Fière. However, the rearguard Gavin left at Chef-du-Pont, at one stage nearly overwhelmed, was suddenly rescued by the unexpected arrival of a glider carrying an anti-tank gun. They in turn pushed their opponents back and seized the southern bridge. To enable his comrades to cross at Chef-du-Pont, the much-wounded PFC Charles DeGlopper, 325th Glider Infantry, covered them with his Browning Automatic Rifle (BAR), but was killed in the process – an action that would bring recognition of his sacrifice in the form of a Medal of Honor.

La Fière would remain contested for three days, both sides realising the defeat of the paratroopers around Sainte-Mère-Église or the advance on Cherbourg would be enabled by controlling this key location, however insignificant it seemed. In the event, the 82nd finally overwhelmed the grenadiers on 9 June, backed up by Barton’s 4th Division and Shermans of the 746th Tank Battalion. Although the Fallschirmjägers may have rated their combat efficiency as ‘poor’, and grenadiers like Ernst Flöter, Paul Golz and Franz Roggenbuck were all ill-trained and ‘not interested in fighting’, at La Fière the 91st Luftlande Division fought like tigers. When GIs were read a G-2 (intelligence) report stating their opponents were second-rate, one suggested ‘putting the Germans on the distribution list because they don’t seem to realise it’.

The panorama from the high east bank at La Fière is exactly as it was in 1944, without the marsh. From there, the operational importance of the several Merderet crossings for the Wehrmacht and Airborne troops is evident, which was why they were so bitterly contested. For the 82nd Airborne, the fighting in and around La Fière rated as the most intense they experienced in the Second World War, reflected by casualties of 569 killed and wounded amongst the elements of the five battalions directed to the vicinity by Generals Ridgway and Gavin. The road leading down to the bridge ‘was continuously dancing with bullet and shrapnel impact as if a giant vibrator was at work’, remembered one officer.16

Of the ground behind, Jim Gavin recalled, ‘The right side of the road was stacked with the poncho-covered bodies of dead troopers. Opposite was the immediate aid station. Wounded troopers were laying on every inch of available space, legs and boots on the road with medics going from patient to patient administering aid, inserting tubes with plasma.’17 Across the river lies the little twelfth-century chapel at Cauquigny, where the railings around the churchyard are still riddled with holes and shrapnel from the three-day firefight of June 1944. On the east bank, a replica of the Airborne Trooper statue at Fort Bragg (‘Iron Mike’) was unveiled on 7 June 1997, standing guard over La Fière today.

Taking Sainte-Mère-Église was the task of Lieutenant Colonel Edward Krause’s Third Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry, which they achieved by daybreak, killing or capturing the forty Germans who had remained to slug it out – the rest having fled. However, this vital route centre was to be the objective of several German counter-attacks, and although beaten off, illustrated how fast the Germans could round up scattered troops and initiate tactical actions.

Corporal William F. Falduti of Nutley, New Jersey, recalled their arrival.

I jumped with my buddy, Peter Black Cloud, a big strapping Indian from North Dakota; we were both 505th and had been all through training and boy, did we raise hell together. When we jumped, the only light we saw was German tracer bullets coming up to meet us. We landed in and around apple trees, and got into a firefight straightaways. I’ll never forget it was apple blossom time. Even now, when I smell the fragrance of apples, I associate it with sharp stench of cordite from discharging weapons. Of the thirty-six in my platoon, only seventeen survived – and my old pal Indian Pete wasn’t one of them.18

It was mainly the 2nd Platoon, ‘F’ Company of the 505th, who were sucked into the night-time centre of Sainte-Mère-Église, though some landed in the darkened countryside beyond. Few who landed in the town square stood a chance against the armed and jumpy Germans, who machine-gunned to death those caught in trees or on buildings. Privates Kenneth Russell and John Steele were lucky to survive the encounter when their canopies snagged on a corner of the church steeple. They were part of a stick of fifteen that floated down into the middle of the town. Russell soon cut himself down; Steele decided that the best thing he could do was play dead and took a bullet to the heel. Eventually he was cut down by Gefreiter Rudolf May and Grenadier Rudi Escher, manning a machine-gun in the church tower, taken prisoner and then carried to an aid station – later, he escaped.

Yards away, Private Ernest R. Blanchard was waylaid by the branches of a tree in the town square but immediately hacked at his harness with a knife, dropped to the ground and ran for his life. Only later did he realise in that adrenalin-pumping moment he had cut off the top of his thumb. Eight of the stick died in the square; one was taken prisoner, two died in the Bulge in 1945; just four of the fifteen survived the night and fought through to the end of the war.19 Through the storytelling of Cornelius Ryan, it is Steele’s adventure that the world now recalls, but the equally dramatic escapes of Russell and Blanchard have been consigned, alas, to the dustbin of history.20

The church of Sainte-Mère-Église (left), where a stick from ‘F’ Company of the 505th PIR landed. John Steele’s parachute caught on the far left pinnacle of the tower; he was captured by two Germans in the belfry. Kenneth Russell landed on the left-hand roof and was about to be shot by a German on the ground. However, the guard was killed by Sergeant John Ray, who had landed in the square; Ray was gunned down, but, in a final burst of life, felled the German who had shot him. Ladislav Tlapa landed in a tree to the left and was executed as he struggled to get free. Ernest Blanchard landed in another tree and was unaware that he had hacked off his thumb to escape. It was from the distinctive eleventh century church tower of Saint-Marie-du-Mont (right), the highest in the region, that Major von der Heydte first saw the invasion fleet off Utah Beach. (Author’s collection)

Woken up by the low-flying aircraft, eleven-year-old Emil Ozouf stood on his bedroom windowsill to watch the paratroopers float down. Living on a farm in Gambosville just outside Sainte-Mère-Église, the following morning he raced through ‘the garden and fields recovering the valuable silk chutes – there must have been about eighty. We spent a memorable few days, wandering the countryside, making friends with the Americans, collecting anything we found. Food, bandages and medicines, military equipment – even weapons. We took it all home, knowing our parents could trade them for valuable commodities or make clothes from the silk. I had a lovely German officer’s side hat which my mother used for ages as an oven glove. My father fixed a handle onto a German helmet and we used it to feed grain to the hens – very appropriate!’21 Local families recall that this unexpected bounty from the skies was often the first taste of chocolate, orange juice or coffee in their lives.

John Steele is still in Sainte-Mère-Église today – or at least his effigy hangs from the church (albeit from the wrong pinnacle), for 6 June 1944 gave the anonymous little Norman town a fame it had never achieved in nine hundred years. Many of the town’s businesses survive off the D-Day pilgrims who visit each year, and the careful eye will pick out the bullet holes in the church’s stone walls. Inside, two modern stained-glass windows depict aspects of the town’s liberation, of paratroopers falling to earth. Across the way, the Airborne Forces Museum has grown enormously from its first opening in 1964, and as well as a Waco glider, it now includes one of the actual C-47s from which paratroopers of the 101st Airborne jumped into Normandy.

Near Carentan, and in charge of the Fallschirmjäger’s 12th Company, Oberleutnant Martin Pöppel – fresh from field training and a map exercise only the day before – received the Invasionswarnung (invasion alert):

All my observation posts are reporting parachute landings. The first wounded prisoners, three Americans, are brought in. The initial interrogations don’t produce any results, though. The fellows have been well trained and just answer every question by saying, ‘I don’t know’. The night is stormy and wild. There are single cracks of rifle fire. From time to time the moon lights up the darkness. More prisoners are brought in, great hulking figures. They look as though they could be from Sing-Sing – and our map exercise has suddenly turned into the real thing.22

As word spread of the first parachutists, Grenadier Otto Bügener, an eighteen-year-old who could have passed for thirteen, scribbled a hasty note to his parents. He recorded ‘intense joy’ that the alarm was sounded. ‘This is the moment we have awaited for so long,’ he wrote, full of confidence they would be victorious. He signed off: ‘I am going to rise to the task ahead of me and I will come back to you shortly; we were read the Führer’s orders and know that this will be the battle for Germany and for Europe.’23

Despite the best efforts of their pathfinders and aircrew, the airborne troopers’ principal enemy proved not to be the Germans but the weather: only ten per cent of the US paratroop force landed on their drop zones. Around thirty per cent were within a mile, and a further twenty per cent within two miles; the British were similarly distributed – though this was nothing like the catastrophe the excitable Leigh-Mallory had predicted. We met Lance Corporal John Ross earlier of the Canadian Parachute Battalion (British 6th Airborne); he and the rest of his 120-strong ‘C’ Company were flown into action east of Caen by RAF Albemarles, ten to a plane, twelve aircraft in total. ‘I would say four of the aeroplanes dropped their men on the drop zone; the rest were badly scattered. The one I was in dropped us right dead on target,’ he observed.24

Ed Boccafogli from Clifton, New Jersey, fought with ‘B’ Company, 508th Parachute Infantry of the 82nd Airborne. He reflected, ‘I was lucky. I landed within, I’d say, maybe hundreds of yards of where I was supposed to. Others landed five miles away. Many of them were killed, because by the time they tried to work their way back they ran into German units.’25 Also arriving precisely on his DZ was Captain Frank Lillyman, leading the pathfinders of the 101st Airborne, and possibly the first American to touch French soil; he had been flown to the right spot by Lieutenant Colonel Joel Crouch, the former United Airlines pilot.

Their flight had been uneventful until they made landfall: Crouch ran into a bank of low-lying cloud and disappeared from the rest of the formation. Instead of following their training and flying through, some climbed above, others below, and the force scattered; fire from the ground compounded the issue, with the result that many sticks of pathfinders were dropped away from their DZs. Overall, After Action Reports noted, the excessive weight carried by individuals caused sticks to be strewn over much longer distances.

Meanwhile, the airborne force had already started taking casualties. Waiting for the green light to go, Lieutenant Bob Mathias, a platoon leader with the 508th Parachute Infantry, was about to urge his men out of their C-47. An anti-aircraft shell burst in his face, knocking him over, yet he still raised his right arm and bellowed out ‘Follow me!’ as he fell into the night. It was 0227 hours – that was the last time his men saw him alive: at daybreak, he was discovered near Sainte-Mère-Église, dead from shraprel wounds, still wearing his parachute.26

In the east near Caen, Private Jan de Vries with the Canadian Parachute Battalion was pulled out of his C-47 by the slipstream, to be met by … silence. The noise and camaraderie of the aircraft faded and disappeared; most paratroopers recalled a sense of being alone as they drifted to earth, which offered a moment of respite.27 David Rogers of the 101st noticed, ‘When my parachute opened, I was directly above the steeple of the church in Sainte-Marie-du-Mont. The moon was full, and there were scattered clouds which made everything on the ground easy to see. It looked just like the picture I had studied so intensely at Upottery.’28 Another 101st man, Lieutenant Elmer F. Brandenberger with ‘B’ Company of the 502nd Parachute Infantry, was surprised when the opening shock of his chute ‘tore the rifle from my grasp. I can still remember the thought flashing through my mind that it would hit some damned Kraut and bash in his head. I landed in the middle of an open field and, as I lay on my back looking up, I could see chutes blossoming out overhead and machine-gun tracers dancing among them like fireflies.’29

Ed Boccafogli fell out of his plane, having ‘slipped on vomit. Some guys were throwing up from nerves, and as we pivoted out my feet went out from under me, and I went upside down.’ The acutely anxious had been sick in their helmets and when the order came to hook up, adrenalin pumping, had unthinkingly put them back on. Boccafogli had spent 5 June trying to console his friend, baby-faced John Daum of the 508th, that he was not going to die on 6 June: ‘Aw, come on. Some of us will, some of us won’t, but you ain’t gonna be one.’ But he was wrong; Daum would die as he’d predicted, and Boccafogli never forgot him.30

Once the German gunners started opening up, some – though by no means all – pilots began to twist and weave to avoid the flak, and other aircraft. This threw the jumpers, formed up in line and waiting for their green light, around within their aircraft, tangling static lines and equipment. Canadian paratrooper Bill Lovatt with the British 6th Airborne Division recalled, ‘as we approached the DZ the aircraft took violent evasive moves, and I was flung back violently from the doorway to the opposite side of the aircraft in a tangle of arms and legs’.31 After one such manoeuvre, Louis E. Traux of the 101st recollected, ‘I was appalled at the view which greeted me – I was the only one standing. Four men lay in a knotted heap on the floor. One man dived out the door first. I stepped over the top of two men. The closest man to the door crawled out head first. I grabbed the ammo belt of the man I thought was next and gave him a heave out nose first. The next man made it crawling on his own power.’32 ‘Before the light changed from red to green, the plane suddenly lurched,’ remembered Sergeant John Feduck in the Canadian Parachute Battalion. ‘I couldn’t hang on because there was nothing to hang on to, so out I went – there was no getting back in’; at least he was over dry land.33

Some C-47s, such as Second Lieutenant Marvin F. Muir’s, held level, ploughing on, though mortally hit by ground fire and in flames, buying time for their human cargoes – in Muir’s case paratroopers of ‘D’ Company, 506th Parachute Infantry – to exit before crashing. Muir’s Gooney Bird from the 93rd Troop Carrier Squadron spiralled down from 750 feet in a huge ball of flame, killing all five aircrew.34 After nursing his ship back to Tarrant Rushton, First Lieutenant Richard Randolph counted 326 bullet holes in his airframe, ‘some as close as six inches from the gas tanks’; they afterwards renamed their C-47 Patches.

Membury-based pilot Don Skrdla, a pre-war rancher from Nebraska, made three circuits over the drop zone with his C-47 of the 81st Troop Carrier Squadron, due to heavy equipment bundles that jammed in the doorway. Only on the third pass did his crewmen free the obstructions that allowed his troopers to jump – coolness that brought him a Distinguished Flying Cross, the only one awarded to his squadron. Other aircraft simply carried on through the overcast sky: ‘I can’t figure out how we went through those clouds without collisions or damage to the planes,’ reflected Sergeant Elmer ‘Wish’ Wisherd, with the 91st Troop Carrier Squadron, ferrying the 101st to their war. ‘I could see the other planes around us taking ground fire. We went back up through the clouds; it was quite a layer of clouds. And we came out in formation! How we did it I have no idea. Our pilots were the best, all instrument-rated pilots. There was no talking between planes whatsoever – complete radio silence.’35

Captain Richard Todd, the future actor, was then assistant adjutant in the 7th Parachute Battalion. Nicknamed ‘Sweeney’ Todd after the fictional mass-murderer of old London Town, the opening minutes of 6 June found him sitting with his feet dangling through the exit hole in the base of a converted Stirling bomber. His batman (aide) held on to him as the aeroplane ducked and dived: the dinghy strapped to his leg was reminder enough of the perils of losing his balance. As he observed, ‘the buffeting of the strong wind on the aircraft caused quite a lot of people to fall out over the sea: none would have survived, weighed down with all their kit and caboodle. It was ghastly; one of my friends died that way; we lost quite a few over the Channel.’36 Earlier he had encountered Lieutenant Henry ‘Tod’ Sweeney of the 2nd Ox and Bucks Light Infantry in the same division. Their introduction went along the lines of: ‘Hello, my name’s Todd, they call me “Sweeney”.’ ‘How do you do. My name’s Sweeney, they call me “Tod”.’ The latter recalled, ‘We were really proud and excited to be making the first foothold in Europe. It was like being selected for the national rugger team, or walking out to open the innings for England at Lord’s cricket ground. We glamorised the invasion as a great crusade and all sorts came to see us off; we had never seen so many red tabs [senior officers] in our lives.’37

Over the Cotentin two 82nd troopers, Roy O. King and Sergeant William T. Dunfee of the 505th, had the shock of their lives when they noticed C-47s below them. ‘I was fascinated by the sight of the tracers flying around everywhere when I saw a huge explosion blossom directly below me,’ recollected King. ‘Somehow I was above the stream of airplanes that had just dropped their troopers and equipment. My immediate concern was that I could be chopped to pieces by the propellers of the oncoming planes.’ Dunfee echoed the fear, having known their pilots would be looking down, not up. ‘That scared the hell out of me, and I started cussing them. I didn’t want to be turned into hamburger by our own air force.’38 Tom Rice of the 101st Airborne remembered getting shot at from the ground through the heavy fog. ‘I had a real hard landing, rolling over on my right arm; I had so much equipment because I weighed 276 pounds. That was all padding – so I didn’t get injured at all.’39 Private William Talbot with the Canadian Parachute Battalion conceded, ‘With sixty pounds of equipment strapped to our legs we couldn’t run out the aircraft door; we just shuffled towards it and dropped out.’40

This was a reminder that in addition to the average paratrooper load – including chute and reserve – of one hundred pounds, many men jumped with heavy kitbags tied to their legs by a long rope, which they were supposed to pay out during their descent. Men watched helplessly as many of these canvas bags fell open or disappeared altogether, scattering heavy weapons, belongings and ammunition into the darkness below. Most units, American, British and Canadian, lost an extraordinary amount of stuff in their night-time drop: up to seventy per cent of support weaponry, ammunition and medical supplies in particular. Much of it remains in the Normandy soil and occasionally surfaces, to the amusement of farmers and tourists.

Dick Winters of the famed ‘E’ Company, 506th Parachute Infantry, lost his kitbag to the slipstream, ‘along with virtually every bit of equipment I was carrying’. Without most of their paraphernalia, Lieutenant Colonel G. F. P. Bradbrooke, commanding the 1st Canadian Parachute Battalion, mused, ‘The hardest part of the job wasn’t the fighting – although that was hard enough at times – but getting ourselves organised after we hit the drop zone.’41

Vince Occhipinti, with ‘F’ Company in the same regiment as Winters, noted ‘the tremendous noise; I could see tracer bullets coming up after me. Here came a tracer, and another, and another. I could see them coming at me from all directions. What was the most horrifying was that in between each of those tracers was five or six other bullets. Then, suddenly the ground was there, and – bam – I hit. I heard a noise not too far from my left, and a large shape suddenly loomed nearby: it said, Moo: a cow just stood there, looking at me’.42

His buddy was Marion J. Grodowski, whose adventurous life had started in Krakow, Poland. His family later moved to Chicago and Grodowski’s D-Day began when ‘a .45 pistol that I had holstered on my hip, as well as my canteen, tore away. I looked up and saw a blown panel in my parachute.’43 Another Screaming Eagle had absolute confidence in his chute: checking it in the plane, Private C. Hillman of Manchester, Connecticut, saw it had been packed by the Pioneer Parachute Company, where his mother worked as an inspector; he knew his luck was in when he read his mother’s own initials on the ticket.

In all three airborne formations, paratroopers sustained injuries on landing. Twenty-nine-year-old Benjamin ‘Vandy’ Vandervoort had been promoted to lieutenant colonel five days before he parachuted into France commanding the Second Battalion, 505th Parachute Infantry. ‘I had a little hard luck on the landing and banged up my foot,’ the young colonel later played by John Wayne in The Longest Day modestly reported later. In fact, his leg was fractured just above the ankle; he merely carried on, tightening up the laces on his boot, and using his rifle as a crutch – until gifted some hand-carved ones by a French civilian.44

A 101st Airborne soldier, Eugene Cook from Ohio, remembered jumping ‘pretty low. I had a hard landing and didn’t know about my broken ankle for a couple of minutes until I got out of my parachute, stood up and fell over. I couldn’t go to find anyone from my stick, so was all by myself for a couple of hours.’45 Cook would fight on for fourteen days with his mangled foot. Lieutenant Russell Chandler, the C-47 pilot, recalled ‘a sergeant of the 82nd, who had taken some shrapnel in the leg. By rights, he should have stayed on board and flown back with us. Instead, he told my crew chief, “I’m jumping, it’s too dangerous in this thing!” And he did. I guess we all have our own perspective of where the danger lies, and I suppose he did get medical attention as soon as he hit the ground, instead of waiting two hours to go back to England with us.’46

American and British doctors scurried around the drop zones and through the night, trying to collect their medical teams, salvage equipment and tend to the injured. Outside Sainte-Mère-Église at around 0235 hours, German medical orderly Fritz Müller, with an artillery battery of the 91st Luftlande, found himself walking in and out of curious shadows – the trees above him were filled with parachutes; some were empty, others still bore the dead. Soon he stumbled on a fellow grenadier looting an American corpse, rifling his pockets, looking through family photos in the unfortunate’s wallet, wrenching a ring off the man’s finger. Müller yelled at him to stop, and the other walked away. Suddenly, Müller recalled, a shot shattered the quiet, and the looter fell dead. Müller froze, realised the American was alive and started to treat him; as he did so, he noticed cigarettes falling around him – other paratroopers trapped in the trees above were showing their gratitude.47

Major Johnny Watts, a consultant surgeon who landed with the 195th Airlanding Field Ambulance, set off towards his dressing station on an ancient bicycle left by a French farmer. En route, Watts suffered an attack of hay fever, but when challenged by an alert sentry, he could neither remember the password nor stop sneezing. Neither could he stop the bike. He spluttered ‘Friend’ as he sailed past and was fortunate not to have been shot.48 His colleague, Captain David Tibbs of 225th Field Ambulance, recalled recovering ‘a dozen men scattered in the corn, mainly with fractured femurs from landing with their heavy kitbags still strapped to one leg’.49

Lieutenant Neal Beaver, the 82nd paratrooper who had had to waddle to a replacement aircraft ‘like a bloated frog’, jumped low: ‘As it turns out, the low altitude was a break also, not one man was fired at in the air.’ However, the pay-off was that he ‘had to leave seven men behind in a French home’ when he moved on at 0800. ‘All had jump injuries: broken arms, two broken ankles, a wrenched back. It was one hell of a tight jump, even by Fort Bragg training standards.’50 British Captain Tibbs was struck by the determination of one young officer ‘who was hopping along on one leg, with the other trailing loosely behind him, obviously a severe injury’, who apologised profusely for being ‘such a damned nuisance’. Later, when his aid post was threatened with capture and a jittery medic shouted out ‘The Germans are here’, Tibbs observed how ‘a badly wounded Glaswegian sergeant levered himself up, picked up a Sten gun lying by his side and pointing it at him, growled, “Stop your blathering, ye f**ker, or ye’ll be the first to go!”’51

Twenty-year-old Robert Elmore had been called up for military service in 1943; a man with strong beliefs, he declared himself a ‘devout pacifist’ to the War Office, but nevertheless volunteered for the 225th as a surgeon’s assistant, where he joined several other conscientious objectors (‘conshies’ to the soldiers who jeered – until they knew better). He recalled the plan to use Ranville church – where Sergeant Herb Fussell had nearly met his end hours earlier – as their dressing station, but on arrival they found its huge oak doors firmly locked. A blast from a Sten gun had no appreciable impact on the medieval woodwork and its ironmongery, so they moved on to a nearby château; as alert villagers realised what was happening, they whispered ‘Bonjour’ from their bedroom windows, Elmore recollected.52

There were combat injuries, too. In the British sector, Major Hans von Luck, with the 21st Panzer Division, recorded how on 5 June near the Bavent Forest ‘The 5th Company of my Second Battalion had gone out on a night exercise, armed with blank cartridges for their rifles – a dangerous situation.’53 Later on, Feldwebel Rainer Hartmetz, one of his NCOs, met them: ‘about forty German soldiers along the road. They were very young – perhaps seventeen – some were wounded and supported by their comrades with a sergeant beside. He addressed us. “They’re recruits. We had a night training when they jumped on us. We had only blank cartridges.” He had tears in his eyes and started sobbing.’54 The training ammunition was deemed necessary because of an incident weeks earlier. On one of the Dives bridges, the sentries had been attacked by some of the 774th Infantry Regiment in an unannounced night exercise. They’d thought it was the real thing and shot back with live ammunition, killing two and wounding several more.55

Besides injury, death threatened in the crowded skies. As Canadian Corporal Tom O’Connell plunged to earth, his parachute tangled with another: ‘they twisted together like a thick rope. I heard the other fellow yell from below, “Take it easy, old man!”’ Both hit France with such force that O’Connell lost consciousness. He was out until midday, waking to find the body of his fellow parachutist was none other than that of his padre, Reverend George Alexander Harris.56 The chaplain, originally from Solihull, England – who had followed his calling to Canada and had been in the army for a year – was thirty-four. He was one of fourteen hundred Canadian chaplains who volunteered to minister to those in uniform. Later a lonely field grave was discovered with his identification discs and Bible on it, but tactfully his mother was told, ‘The losses of the unit were so heavy that it is possible we will never know further details.’57

The marshy areas flooded beforehand by Rommel also claimed many lives. ‘Looking out of the plane it looked like pasture below us, but when I jumped, I landed in water,’ recalled Doug Morrison of the Canadian Parachute Battalion. ‘The Germans had flooded the area a while back and there was a green algae on the water so it actually looked like pasture from the air.’58 John M. Marr, a rifle platoon commander in the 507th Parachute Infantry of the 82nd Airborne, dropped into the inundated Merderet river, which looked from the air like a very wet meadow. ‘It was armpit deep, in some parts well over the head,’ he remembered. ‘We were strung out in a long drop; I was the jumpmaster on my plane and the last two of my platoon to get out were immediately captured. I was all alone.’59 Marr was one of the lucky ones: it is estimated that in the opening hours of D-Day more paratroopers died plummeting into silt and mud than from enemy action.

‘I am giving you a grade-A stinker of a job,’ Brigadier James Hill had told twenty-nine-year-old Terence Otway. The new CO of the 9th Parachute Battalion, with the British 6th Airborne Division, who had connived at the removal of his predecessor, the patrician Martin Lindsay, was quick of temper, did not warm to people easily and resented those around him with a better station in life. Otway had to put all this aside and ready himself for his mission: to take four German artillery positions at Merville.

There were several more dangerous German batteries east of the Orne that threatened the invasion: six 170mm guns at Houlgate and six 155mm cannon at Berneville, for example. However, the shortage of commandos for the many proposed tasks, coupled with the RAF’s bullish insistence that they could neutralise both these sites – as well as Merville – led to their capture being scaled back as two reserve missions (code-named ‘Frog’ and ‘Deer’, respectively), should the need arise. Both these sites would be bombed by the RAF and shelled by the Royal Navy – without effect. Curiously, the Merville mission survived as it was the nearest to the 6th Airborne’s drop zone, but was the least important of the three.

The site was five miles distant as the crow flies from the dramas at Pegasus Bridge, but hidden by the bulk of the Bavent–Bréville ridge. Otway’s opponent was twenty-four-year-old Leutnant Raimund Steiner, promoted as battery commander when his predecessor had been killed in a bombing raid on the position. An Austrian, Steiner was no friend of the regime, his father having died as a result of detention in Sachsenhausen concentration camp in 1940, but as a professional soldier he took pride in doing his duty.60 Otway was not sure of the calibre of Steiner’s guns, which were connected to a fortified observation post on the coast, a mile away. According to the local Maquis and aerial reconnaissance, the weapons – inspected by Rommel and Admiral Ruge twice, on 29 January and 6 March – lurked in huge concrete casemates. The site had been regularly bombed without result, the Allies reasoning that such big structures held long-range weapons, potentially lethal to the invasion fleet. Otway devised a complex plan that required a bombing raid shortly before his men arrived in waves by parachute and glider; if all else failed, the cruiser HMS Arethusa was scheduled to open fire on the position at 0530.

The thirty-two C-47s carrying Otway’s army flew over the English coast at Worthing, Sussex, thirty-four minutes behind Howard’s glider force. Flight Lieutenant Stanley Lee, piloting one of No. 512 Squadron’s C-47s, recorded cross-winds ‘up to twenty-five knots [39mph] from west to east, which carried the paras further eastwards’. There was little flak, but ‘with about 250 aircraft dropping the rest of 3rd Parachute Brigade milling round at different heights, the air turbulence was quite violent at times’. The busy Lee ‘did three trips to Normandy and back that day’.61 Soon everything began to unravel for Otway: the Lancaster raid – one of ten on coastal batteries which began at 2331 hours on 5 June – only managed to hit a herd of cows, not the concrete emplacements, and killed twenty-four of his own advance party.

Of 650 men parachuted into the area, only 160 could be found in preparation for Otway’s assault on Steiner’s position. Many of the missing had landed in Rommel’s flooded fields, inundated by the River Dives, whose brackish waters drowned many a helpless warrior weighed down by his kit. Others, disoriented, were captured, including two who had the misfortune to land in front of Generalleutnant Josef Reichert’s 711st Divisional headquarters further east, near Honfleur. The general, playing cards with his staff, was momentarily stunned, and wondered if this was an attack on him, or a drop of personnel to the local Maquis. He reported their presence at 0126 hours to his corps commander in Rouen. As Reichert was stationed east of the inter-army boundary, it was Salmuth’s Fifteenth Army – already on alert – who received the news. When Salmuth phoned Reichert’s headquarters directly to ask ‘What the Devil is happening down there?’, a firefight with more British paratroopers had broken out. By way of reply, Reichert held the telephone receiver out of the window and Salmuth clearly heard the exchange of automatic fire down the line. Dollmann’s Seventh Army, as we have seen, were also alerted at this hour, but by Richter of the 716th Division in Caen, and to a different clash with paratroopers.62

The turbulence that affected every aspect of Overlord played havoc with Otway’s eight-strong glider force: one returned to England with a severed tow rope; another ditched in the Channel, drowning all on board; five missed the landing zone by miles; and just one landed nearby. A ninth, on a different mission entirely, happened to crash-land on the objective in flames; one of its occupants emerged as a human candle, having been hit by ground fire, which ignited his flamethrower. This alerted the Germans to the imminent attack. The mercurial Otway appears to have suffered a brief crisis of confidence, possibly even a brief, private breakdown, complaining to his batman, Corporal Joe Wilson, that he ‘didn’t know what to do’. The unperturbable Wilson sometimes felt his job was to act as a Jeeves-like confidant to Otway’s frequent outbursts of temper. On this occasion the former valet calmed his master with the hip flask of brandy he had ready for such occasions. When Otway was finally in a position to assault, he did so two hours late, at 0430, with few weapons and a quarter of his original force.63

Corporal Edwin Booth, last encountered flinging folding bicycles on parachutes out of aircraft during a pre-invasion exercise, recalled that Otway’s advance party, which had preceded the main body, had managed to cut a passage through the barbed wire surrounding Merville. ‘As no engineers turned up, we went on through the minefield beyond by feeling our way with bayonets, marking our progress with our heels. All the equipment we needed to destroy the guns was missing, but Colonel Otway had reorganised the parties into small squads to do the various tasks he planned; then as time was short, he ordered “Let’s go” – and off we went.’ They charged into the position and after fierce fighting with heavy casualties reached the guns, disabling the weapons by removing their breechblocks. ‘On the signal to retire’, remembered Booth, ‘we had to leave the dead and seriously wounded behind; out of the 160 of us, only about sixty-five came out.’64

The Germans had lost around twenty-five killed, each side taking about twenty prisoners, whereupon Otway’s signals officer, Lieutenant James Loring, pulled a dishevelled carrier pigeon from his jump smock, attached news of their success to a canister on its leg and threw it into the night sky – and watched it head towards Germany. (In fact, it successfully made a ‘home run’.) As the darkness began to fade, Otway’s men managed to fire a yellow signal flare, at the very last minute calling off HMS Arethusa’s naval gunfire. Instead, Steiner, from his observation post (OP) on the coast, called down fire from other German positions on his own battery, killing many of Otway’s wounded left in the open. With the ‘streaks of red and gold ranging across the sky’, heralding the sunrise of 6 June, a USAAF bombing raid further exacerbated the Allied casualties, injuring Otway’s brigadier, James Hill, and killing Private Emil Corteil with his German shepherd Glen, among scores of others: the 9th Parachute Battalion would take the heaviest casualties of any British battalion in the 6th Airborne – 423 out of 650 or sixty-five per cent.

Many myths arose about the Merville assault. One is that instead of the four Krupp–Rheinmetall 150mm cannon that Allied intelligence had suggested, possessing all the potency of a six-inch naval gun with a range of thirteen miles, the weapons were found to be of only 75mm calibre, with a range of about six miles, thus bringing into question the entire validity of the mission. This is nonsense; in fact, the Merville casemates contained Czech 100mm wheeled guns, which could throw a thirty-pound shell eight miles, still dangerous to the Allied armada lurking off Sword Beach, six miles away.

Another myth, repeated by writers who parroted Otway’s account of the battle, is that the guns were destroyed on capture. Otway was mistaken: on his departure the site was retaken by the Germans, who reinserted the hastily removed breechblocks. Merville artillerymen Hauptwachtmeister (Battery Sergeant Major), Hans Muskotte and Kanonier Hans Staab recalled that the resourceful Steiner (who had controlled the defence from his coastal observation post initially wearing only his pyjamas) brought all of his weapons back into action, despite a later attack by commandos. The German guns stayed in battle-worthy condition, a little pocket of the Wehrmacht surrounded by the Allies, until Steiner successfully evacuated them under the noses of the British on 17 August.65

While not wishing to denigrate the bravery of the 9th Parachute Battalion’s assault, it is clear that Otway’s plan was certainly overcomplicated, proved less successful than Howard’s, and neatly illustrated the pitfalls of night-time airborne operations. The military analyst in his comfortable armchair might be left wondering if the unit’s original CO, Lieutenant Colonel Martin Lindsay, author of a much simpler scheme, might have pulled off a more successful mission. However, the battalion had distracted Merville from firing on the fleet during D-Day. Otway never forgave the RAF for ‘losing so many of his men’; nor did he accept that his men had failed to disable Steiner’s guns. Obdurate and uncompromising until his death in 2006, Otway refused Steiner’s hand when the pair met in the 1990s. When I first visited the Merville site in 1975, the muddy bunkers were occupied by cows. Having been cleaned up by the 10th Field Squadron, Royal Engineers, in 1982, the Merville Battery today is a thriving museum, containing a C-47 and a Czech 100mm cannon of the type Raimund Steiner commanded so resourcefully in 1944.66

One of Otway’s missing gliders had parted with its glider tug over the Channel, but the pilots had enough height to turn back and land in a cornfield. Before the aircrew could warn their passengers, Otway’s men burst out, assuming this was Merville. Adrenalin pumping, they spied an airfield, crept up on the control tower and burst in, temporarily mistaking the RAF blue uniforms for Luftwaffe field grey. WAAF Audrey Hirst, on duty in the control tower at RAF Tangmere, near Chichester, West Sussex, was surprised when the door was suddenly flung wide open and in rushed several soldiers in full battle gear, dripping with hand grenades, waving Sten guns. Stunned into silence by their painted faces, camouflaged tunics and menacing weapons, the duty officer raised his hands in surrender as they demanded – in German – the airfield be surrendered ‘in the name of the King’. With her CO a nervous wreck, it was Hirst who took charge of the situation, rounded them up, gave them tea and organised transport back to their base, so they could continue their war elsewhere.

The bulk of the 3rd and 5th Parachute Brigades with four hundred supply containers had landed in France from 0050 onwards; with them, as one of the first British doctors in Normandy, was David Tibbs with the 225th Parachute Field Ambulance. He vividly recalled looking out of his C-47 and ‘seeing a white line that was the surf breaking on the Normandy coast’. ‘In the split second before my medical section of twenty jumped, a four-engined Stirling suddenly appeared, cutting diagonally across our path. Collision seemed inevitable, but both pilots took evasive action, and everyone was sent sprawling across the floor. Ours – Flying Officer Peter Hakkansson, a Norwegian who gave us immediate confidence – swiftly corrected the plane, the green light came on and I jumped into the darkness.’67

Following them, sixty-five Horsa and four Hamilcar gliders transporting the 6th Airborne Division headquarters and an anti-tank battery were shortly to appear. To clear the area, Lieutenant Colonel Peter Luard’s 13th Parachute Battalion seized Ranville, earmarked for General Gale’s headquarters. On 6 June, his thirty-third birthday, Luard assembled his men, blowing the hunting horn he’d brought along for the purpose. General Gale, headquartered in the Château de Heaume at Le Bas de Ranville, would later ride around inspecting his troops’ positions on a white stallion found in a nearby field by his batman. Towed by Stirling bomber across the Channel to Ranville on his twenty-second birthday was glider pilot Staff Sergeant Laurie Weeden, carrying a jeep with its trailer and four soldiers. He squeezed his sixty-seven-foot Horsa onto a field near Ranville and was twice waylaid by helpful Frenchmen – the first confirmed for him where he was on the map; the second gave him two bottles of beer.68

Meanwhile, the 521st Parachute Squadron, Royal Engineers, swept the nearby landing zone of ‘Rommel’s asparagus’ wooden poles. John Howard remembered perplexed Italian forced labourers turning up to install the anti-landing staves. When he told them ‘their services were no longer required; they had been liberated; they were free’, they nodded, thanked him profusely – ‘and then the silly sods carried on hammering in their stakes’.69 With or without the help of the Italians, the clearing work ended minutes before the arrival of the first gliders bearing Gale and his staff, at 0335 hours.

It was only much later in the campaign that the 13th Parachute Battalion learned that one of its soldiers, Private Robert Johns, had enlisted in the army aged fourteen, hoodwinking the recruiter that he was all of the eighteen years he appeared to be. When he jumped into Normandy on D-Day, Bobby Johns was just sixteen, which is the age that appears on his headstone, for he was killed by a sniper on 23 July – after his parents had found out where he was, but before the authorities could haul him back. ‘I remember him well,’ his platoon commander later recalled. ‘He was a very big chap – capable, fearless, and loved being a paratrooper. I never suspected that he was underage and it was not until after his death that we were informed that he was just sixteen.’70

British airborne forces relied on the large Airspeed AS-51 Horsa glider which could carry between twenty-five and thirty troops (depending on their combat loads), a jeep, a trailer or an anti-tank gun into battle. They brought John Howard’s men to their bridges and the 6th Airlanding Brigade and their divisional headquarters into Normandy. 222 Horsas were also used by the two US airborne divisions. An American Horsa is seen here, the cows giving a sense of its 67-foot length and 88-foot wingspan. (US Army Signal Corps)

Throughout Normandy, many paratroopers were taken prisoner in the first hours. Corporal Jack Schlegel, who had come across General Falley’s body, was surrounded by men from the latter’s division later on 6 June. ‘The next day we were loaded onto twenty German trucks with canvas covers; about noon Allied planes strafed our convoy, killing thirty to forty men, many from the 508th,’ he remembered. On his fourth escape attempt, from a hospital in Rennes, he would make it back to Allied lines.71

For Joseph R. Beyrle of Muskegon, Michigan, 6 June would prove to be the beginning of a very long journey indeed. The sergeant with ‘I’ Company of Bob Sink’s 506th Parachute Infantry recalled jumping onto the church roof at Saint-Côme-du-Mont, and was captured by a dozen German Fallschirmjäger. He was sent to various POW camps in Germany and, aided by his proficiency in German (his grandparents had emigrated from Bavaria, so he was bilingual), escaped in January 1945, heading east towards the Russians. He surrendered to a battalion of the 1st Guards Tank Army equipped with Shermans and led by Aleksandra Samusenko, the most senior female tank officer in the Russian forces.

She allowed him to fight with her unit, but he was eventually wounded in the advance to Berlin and evacuated to a Soviet field hospital. There he received a visit from Marshal Zhukov, who learned of Beyrle’s story and arranged for his passage to the US embassy in Moscow, where his credentials were confirmed. The paratrooper returned home two years after he had left the United States to find he had been officially listed as killed in action and a memorial mass had been said in his honour. Beyrle remains the only soldier to have fought in US and Soviet forces during the Second World War.72

In the British sector, two young members of the 8th Parachute Battalion were setting up homing beacons for the rest of their battalion near Toufreville, when they were surprised by a patrol from the 6th Company of Major Hans von Luck’s 125th Panzergrenadier-Regiment. They were taken down a farm track and shot in the back of the head, a crime uncovered by a local civilian taking an early-morning stroll before news of the landings had spread.73 However, British parachute doctor Captain David Tibbs later conceded that his general, Richard Gale, had told them all in a pre-invasion briefing, ‘I don’t want any bloody nonsense about taking prisoners. You are there to kill Germans!’ Tibbs himself went to great lengths to treat German wounded equally to his own.74

Combat, particularly between the pumped-up airborne units, was brutal, and would remain so: Manfred Vogt, with the Fallschirmjäger’s 4th Company, would witness the ill treatment of German casualties whilst hiding in a Cotentin swamp: ‘a few Americans gave one of our wounded a good once-over. With fists and the butts of their weapons, they beat the poor guy and kicked him with their boots. When he could no longer move, one of the Americans put his boot on the guy’s head and pushed him into the water until he drowned.’75 Perhaps more typical was the reaction of an American glider pilot, George E. ‘Pete’ Buckley of the 74th Troop Carrier Squadron, who related finding a German ‘lying at a road junction in a pool of blood. He had just been hit by a mortar or shell fragment and was still alive. I felt horrible as I stood there watching him die knowing there was nothing I could do for him. I still had not developed the hate for the enemy – that came to me as the day progressed, when I saw and heard what they did to some of our airborne men. This German, lying in front of me, was a young kid, and sure didn’t look like a Nazi Superman.’76

Near Carentan, Oberfeldwebel Pelz captured some paratroop officers: ‘They were crowded around a map, shining their dim flashlights on it. They were so concerned with reading the map, that they didn’t even notice they had been encircled. They hadn’t put out a sentry: they were so confident of victory.’77 This accorded with the recollection of Spencer F. Wurst, a 505th Parachute Infantry staff sergeant with ‘F’ Company: ‘It may seem naïve now, but at no time did we ever dream that we would not be successful in Normandy.’78 Pelz’s Fallschirmjäger comrade Feldwebel Eugen Griesser recorded his first prisoners, ‘mostly young boys around twenty, big and strong guys. They wore combat uniforms with sewn-on pockets in which they carried half a colonial wares stores: rations in cans, chewing gum, chocolate, reserve ammunition, pictures of naked girls and even explosives.’79

Other German reports noted the British carried an escape kit including ‘a tiny German phrase book; silk map; an oilskin-wrapped hacksaw; miniature compass; cream-coloured dominoes which turned out to be dehydrated porridge with milk; what looked like gaming dice, which were in fact cubes of tea, milk and sugar; and chocolate in a tin’. They also wondered at the cans of Heinz self-heating soup, which soon became known as selbstfahrende suppe (self-propelled soup). These ingenious cans caught the imagination of every serviceman and civilian who encountered them, recalled Henri Biard, a young civilian then living in Trévières who had just finished his baccalauréat exams: ‘all you had to do was remove a seal from the lid for it to heat up. When I discovered that, my faith in the Allies’ final victory soared sky high!’80

The German paratroops also observed that their opponents ‘were equipped with small metal frogs, a child’s toy that clicked when you pressed on it’.81 The Americans knew these as crickets. Near the Saint-Marcouf battery, Oberleutnant Grieg of the 709th Infantry Division heard frogs croaking loudly in a marshy area where there had never been many frogs. Then Obergefreiter Hermann Nissen and Gefreiter Albrecht Müller brought in an American prisoner, holding ‘his ratchet to make a sound like a croaking frog’. Müller called with his captured frog: ‘Revit.’ From elsewhere in the swamp came a response: they could use the device to trap the others, and crept towards the answering frogs. ‘Soon there were no more frogs croaking and twenty prisoners: a truly fat catch.’ ‘Rev-it, rev-it,’ grinned Grieg as he locked them in an empty bunker. He soon stopped grinning when he inspected the Americans’ escape kits: ‘compasses in buttons on a shirt, tiny new testaments and silk neckerchiefs with maps printed on them: the detail was terrific, with every obstacle and machine-gun nest recorded’. His opponents knew more about his own defences than he did.82

Demonstrating the epitome of journalistic skill in an era when news was restricted to wireless, papers and newsreels, Chester Wilmot, an irrepressible Australian who had transferred to the BBC earlier in the year, recorded his D-Day glider descent near Caen for the BBC:

With grinding brakes and creaking timbers we jolted, lurched and crashed our way to a landing in Northern France early this morning. The glider in which I travelled came off better than most … All around us we can see silhouettes of other gliders, twisted and wrecked – making grotesque patterns against the sky. Some have buried their noses in the soil; others have lost a wheel or a wing; one has crashed into a house, two have collided with each other. Troops are clambering out almost as casually as they might leave a bus. Some have to slash away the wooden fuselage before they can get out their Jeeps and trailers … A German battery is firing out to sea, and from positions all around us the opposition’s ack-ack batteries send up streams of tracer. The airborne forces have gained their first foothold in France by a daring night landing – but all of us know it will be harder to hold the ground than it has been to take it.83

Lieutenant Colonel Mike Murphy, meanwhile, was having trouble with his glider, The Fighting Falcon. It had been bought for the war effort by the children of Greenville School, Michigan, where the ship was built. In April 1943 they had sold $72,000 in war bonds and stamps, in recognition of which it was decreed that theirs – the Falcon – would be the lead glider into Europe. Murphy knew he was taking Brigadier General Don Forrester Pratt, assistant divisional commander of the 101st, into battle with his jeep, but was unaware that the general’s staff had installed armour plates on the vehicle for extra protection. Murphy recalled the Falcon, overloaded by a thousand pounds, ‘handled like a freight train’. Consequently, he hit the ground far above the normal tactical speed of 70mph. When he applied the brakes, nothing happened as the Falcon continued to slide downhill on wet grass the full length of the landing zone before crashing into a Normandy bocage hedgerow.

Murphy came to in his mangled cockpit with two broken legs, his co-pilot dead, just as a column of German vehicles halted nearby. Trapped in his seat, the colonel played dead while several Germans nosed around inside for a few minutes, then departed. The surgeon from Murphy’s No. 2 glider, Dr Van Gorder, trotted over to treat Murphy, then found General Pratt still in his jeep, seat belt fastened, chin on his chest, with a broken neck; he had died instantly. Buried soon after, his Grave Registration Form No. 1 noted the personal effects found on the body: ‘eyeglasses and case, cigarette case, picture case, wallet containing one dollar and 1,500 French francs’.84

Within the first hours of D-Day, each side had lost a general. Pratt’s superior, Maxwell Taylor, commanding the 101st Airborne, whom Eisenhower had seen off from Greenham Common, meanwhile had landed completely alone, later recording that ‘any order he might have given in the following thirty minutes would have been received only by a circle of curious Normandy cows’. His opposite number, Matthew Ridgway of the 82nd Airborne, who had been about to ride into battle by glider, changing his mind to jump at the last moment, made in retrospect a fortunate choice.

Both the RAF and USAAF were widely denounced at the time and afterwards by airborne troops, for their ‘incompetence’ in widely scattering their passengers. Amongst the most vociferous of critics was Lieutenant Colonel Otway, subsequently author of the British Airborne’s official history.85 On the other hand, glider pilots who generally landed on target, and their tug aircrew usually escaped such harsh judgement. Here, we should remember that British aircrew of the Glider Pilot Regiment were expected to fight as infantry after their feats of flying, whereas their American counterparts were quite logically evacuated back to fly more aircraft: thus, seventy-one of the 196 glider pilots who landed with the British 6th Airborne on D-Day would become casualties – mostly by ground combat rather than from injuries sustained during their crash landings.

Later in the narrative of D-Day, a series of authors pounced on the ‘mixed performance’ of the airborne forces in Normandy to allege this was solely the fault of the troop carrier pilots, who themselves were rarely interviewed for their side of the story. Some writers went as far as to allege ‘near-criminal carelessness’ in the way the American pilots released their parachutists, despite the fact that twenty-one aircraft were lost, 196 damaged and ninety US aircrew were killed or wounded over the Cotentin.86 In fact, careful analysis suggests that paratroopers belonging to the 501st, 502nd or 506th Parachute Infantry were statistically more dispersed than their colleagues in the 82nd Airborne Division, who criticised their aircrew less. Often overlooked, the troop carriers also brought back ninety paratroopers for various reasons – some were injured or wounded in flight – with a recorded nine Americans who actually refused to jump; a few who may have similarly hesitated were pushed through the exits by their livid comrades.

The effective remedy against one British paratrooper who faltered and ‘braced himself against the frame of the doorway to prevent himself from going through it’ was for the corporal behind to swiftly ‘chop the defaulter’s arms away and use the forward momentum of his own body’ to ram him ‘into the slipstream beyond’.87 Most non-jumpers, though, had been wounded in flight. Charles S. Cartwright, piloting a 62nd Troop Carrier Squadron C-47 over the Cotentin, recalled two rounds of flak hitting a paratrooper in his plane, which detonated two of his hand grenades. Attempting to fly the seriously injured man back to England, Cartwright’s plane came down near Utah Beach. The five-man crew and wounded paratrooper endured an uncomfortable D-Day, in hiding and under hostile and friendly fire, before making contact with troops advancing from the beach.

Yet the weather, never mind the Germans, should have gone a long way towards exonerating the troop carrier pilots of ineptitude. The 313th Troop Carrier Group reported soon after returning from their first mission over Normandy on 6 June:

Attempted to follow prescribed route, but unable to do so because of weather, which caused group formation to break up completely, aircraft then proceeding individually to DZs. Cloud cover ten-tenths, with base of nine hundred feet, up to eight thousand, which extended to south coast of England … Ceiling then lifted and visibility improved, and at designated DZs there were scattered five-tenths clouds cover with base of four thousand feet, and visibility ten to twenty miles.88

Terrain also made a difference: though the British 6th Airborne were likewise strewn over the Normandy countryside, in their sector there was much less bocage to split up groups and isolate individuals than there was in the Cotentin. Patient examination of the maps drawn up after the war of where each individual American paratrooper stick landed indeed shows the scattering, but prompts as many questions as it answers. The charts were based on the paratroopers’ own reports made at least a month after their drop, and often longer. In the intervening period, the men had had to drag themselves out of slimy marshes, zig-zag through the night to rendezvous, avoid German patrols which captured many, and fight a lengthy campaign against a determined enemy.

Despite their efforts, as one pilot later wrote, ‘only God and his recording angels know precisely where all the paratroopers landed’.89 In the words of another, ‘the Americans knew what was happening, but few of them knew where they were; the Germans knew where they were, but none of them knew what was happening’.90 A military psychologist observed that the airborne troopers were actually angry and fearful at finding themselves alone, or in small groups, not in discovering they were far from their drop zones. After all, the divisions were educated to expect they would end up isolated, behind enemy lines.

Despite the undoubted courage of the C-47 aircrews – as we have witnessed in this mosaic of airborne experiences – complaints like Otway’s, and accounts of 101st paratroopers such as Donald Burgett’s, with ‘A’ Company, 506th Parachute Infantry, have dominated post-war accounts:

Another plane came in low and diagonally over the field. The big ship was silhouetted against the lighter sky with long tongues of exhaust flame flashing along either side of the body. Streams of tracers from several machine-guns flashed upward to converge on it … Then I saw vague, shadowy figures of troops plunging downward. Their chutes were pulling out the pack trays and just starting to unfurl when they hit the ground. Seventeen men hit before their chutes had time to open. They made a sound like large ripe pumpkins being thrown down to burst against the ground. “That dirty son of a bitch pilot,” I swore to myself, “he’s hedgehopping and killing a bunch of troopers, just to save his own ass. I hope he gets shot down in the Channel and drowns real slow.”91