30

Omaha: E-3 – the Colleville Draw

‘It was an endless day. I expected to die any minute. As soon as the ramp on our boat went down, one of the three lieutenants aboard was killed. We stepped over his body into water that was up to our necks. We had to keep our rifles dry, so we walked with them raised above our heads. I’d just gotten out of the water when I saw a ring of guys laying around, about a dozen of them, all from my assault boat, every one of them dead. The shell had hit that close. If I had been with them, I would have been killed.’

Daniel L. Curatola, Third Battalion, 16th Infantry1

The defenders overlooking the Colleville draw were waiting. Their fire discipline was excellent. Colonel Taylor’s men grew closer. Then Oberleutnant Frerking heard the slow rat-tat-tat of Gefreiter Gockel’s old machine-gun, and the grenadiers around him opening fire; their two mortars coughed. As Gefreiter Severloh unleashed his MG-42 fire at the invaders in the shallows, Frerking bellowed, ‘Aiming point Dora, fire!’2

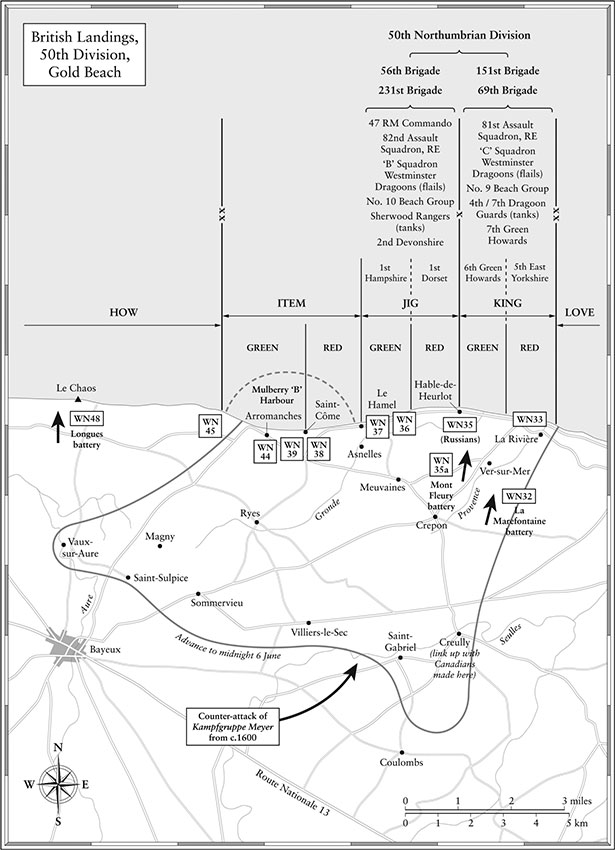

As with all the units landing on Omaha, those who arrived near the E-3 draw leading to Colleville had expected to be landing a mile further west, in the vicinity of E-1. Instead, disembarking from the Henrico at 0415 hours, the 16th Infantry’s Company ‘E’ (whose lone boat containing Lieutenant Spalding had been on target) landed either side of the Colleville draw. On their left were other LCVPs with Company ‘F’. Joining them, and way off course, were men from Company ‘E’, 116th Regiment – a 29th Division unit – whose four LCAs beached near WN61. The same drift applied to Companies ‘I’ and ‘L’, originally scheduled for E-3 – they were carried even further eastwards and ended up under the cliffs of Fox Red sector, on the far left-hand edge. The latter would prise open the final draw, F-1.

Unfortunately for Companies ‘E’ and ‘F’ beaching in front of the E-3 draw, they were setting foot in another ‘Devil’s Garden’, dominated by two of the strongest of the fourteen strongpoints overlooking Omaha. WN62 and WN61 were each manned by twenty to thirty men from the 3rd Company of the 716th Grenadier-Regiment. Alongside them were artillery observation posts for the gunners of the 352nd Division. Despite Rommel’s urging, WN62 had not been completed by 6 June, though the 88mm bunker opposite at WN61 had been finished on 25 April.

The latter, encased in thick concrete, swept the entire beach in concert with another in WN72 at Vierville; these were unusual in being near the beachfront, but heavily protected by aprons of barbed wire, booby traps and mines. Most other positions were up on the heights. Two 75mm guns in WN62 also enfiladed the beach westwards, as did a single 75mm at WN60, with a tank turret-mounted machine-gun. Everywhere were numerous mortar pits and machine-guns housed in Tobruks. (The concrete positions are all still evident to the trained eye today, searching among the brambles.) Collectively, these Widerstandsnester dominated the shoreline with carefully preregistered fire zones, which paid dividends straight away.

Approaching the E-3 draw, Lieutenant William G. Pepe, 5th Engineer Special Brigade, remembered thinking, ‘So here I am, Mines and Booby Traps Officer in Headquarters Company, with a bunch of other civilians in olive drab, playing at soldiering. An IQ of 110 had sent me to Officer Candidate School for ninety days – which is why we young officers were the “ninety day wonders”. I was now entitled to make life and death decisions.’ Pepe ‘bobbed around’ in his staging area, while the twelve boats of his wave assembled. ‘In such extremely tight quarters, we were soon wearing each other’s breakfast,’ Pepe recollected. ‘On coming ashore I immediately ditched my carbine when I saw a discarded .45-caliber Thompson – I never thought what had happened to its owner.’3 With an air of bitterness shared by all the attackers, Pepe observed, ‘We searched for bomb craters, vital for our survival; the Air Corps had promised us one hundred tons of bombs for every five hundred square yards of beach; sure enough, we found the craters two days later – three miles inland.’4

As the assault wave landing craft slowed to negotiate the obstacles, one gun put two rounds into an LCVP carrying naval demolition personnel, killing and wounding fifteen men; only four men got to shore. The incoming tide also played its part in forcing engineers away from their work on the obstructions, and they were obliged to seek the shelter of the cliffs at Fox Red, on the far eastern end of the beach. Engineer tankdozers were of little help, their strength reduced to a single machine: of sixteen Shermans equipped with bulldozer blades, only six got ashore, and five of them were soon picked off mostly by WN62 – leaving a single tank available for fire support for over a mile of the 16th Infantry’s front.

Other fire support which might have come from the division’s artillery battalions, or the Regimental Cannon Company, was not forthcoming. The latter’s six 105mm howitzers sank aboard their DUKWs; the gunners who made it ashore fought as riflemen. The story for Lieutenant Colonel George W. Gibb’s 7th Field Artillery Battalion echoes that of the 111th Artillery supporting the Blue and Gray Division: they lost six of their twelve DUKW-borne guns, had been given the 111th’s last howitzer – ‘the Chief’ – but did not in any case beach until after 1400 hours because of the congestion and shelling. The 7th’s guns would be the only artillery on Omaha to get ashore and into action – at 1615 – on D-Day. The 62nd Armored Field Artillery with their 105mm tracked ‘Priests’ were delayed until near nightfall for similar reasons.

The men from Taylor’s Second Battalion – Companies ‘E’ and ‘F’ and some of the 116th Regimental Combat Team – ran straight into the same kind of disaster that befell Company ‘A’ at the Vierville draw. Not every German position was encased in concrete, however, and that of Gefreiter Franz Gockel was a dugout halfway down the bluffs, protected by logs and sandbags. He had a First World War-era water-cooled Polish machine-gun sitting on a tripod mounted on a wooden platform – under which he had sheltered during the bombardment earlier. This was in every sense an echo of his own father’s experience of the Western Front of 1916–18 – and a reminder of the vast array of captured weaponry the Wehrmacht used in Normandy. Ironically, Gockel was operating a Polish copy of the US Army’s M1917 machine-gun, being used on the beach against him.

WN62 was mostly complete, with their underground troop bunker finished in May. On the forward slope were two huge casemates, each facing west and housing a wheeled 75mm gun, but these lacked armoured shutters and doors.5 Twenty-two-year-old Henri Leroutier was a local Frenchman forced to help build the defences, when he should have been working on the family farm at Saint-Laurent. ‘I worked on a big bunker at Colleville-sur-Mer, with about thirty others,’ he reminisced. ‘We were supervised by only two Germans, which allowed us to sabotage the work by hiding or slowing things down as much as we could. For example, we let the wagons that we used for carrying the sand and gravel roll down to the bottom of the cliff. We couldn’t do it too often or they would come down hard on us.’ He remembered the naval bombardment of 6 June – ‘from about 0600 hours artillery shells fell continuously in our fields. We went up to the attic and saw the sea full of boats, the aeroplanes dropping bombs, then hurried down to a prepared shelter trench to protect ourselves.’6

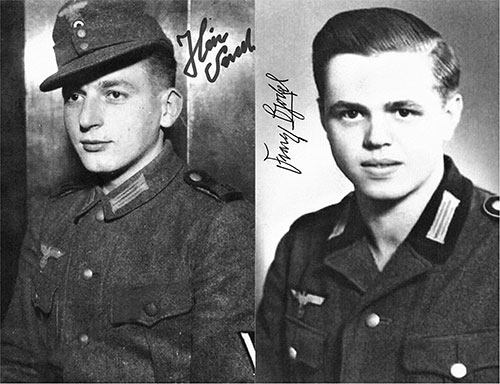

Gefreiters Heinrich ‘Hein’ Severloh (352nd Division) and Franz Gockel (716th Division) manned different bunkers within the WN62 complex. Their Widerstandsnest – cleverly sited on a spur overlooking the Coleville draw and the beach – was the strongest of all on Omaha. It stymied all attempts to open the E-3 exit until 1530 hours, by which time it had run out of ammunition and was outflanked by Company ‘G’ of the 16th Infantry. Both men were fortunate to escape alive; most did not. The site now houses the 1st US Infantry Division’s memorial. (Author’s collection)

Given time, no doubt Gockel would have had his own concrete bunker, too, but for the moment, with his weapon oiled and ready, ranges worked out to every landmark in front of him, the young grenadier was prepared for his first battle. A hundred yards away uphill, still within the perimeter of WN62, was the observation post of Oberleutnant Frerking and Gefreiter Severloh, with No. 1 Battery of the 352nd Division’s artillery regiment. Cramped and accommodating a maximum of three, it had been hardened against shelling only in the spring. Alongside Severloh with his MG-42, Frerking held the field telephone close to his mouth: ‘Aiming point Dora, charge two, impact fuse, entire battery baseline direction, plus twenty, forty-eight-hundred-fifty. Wait for my order to fire.’

With no cover apart from a slight mound of shingle, from which bullets ricocheted alarmingly in all directions, the 16th’s ranks were soon depleted. Company ‘E’ would lose its commander, Captain Edward F. Wozenski, and 104 men before the morning was through. To Captain William A. Friedman from Manhattan, the 16th’s regimental S-1 (staff officer in charge of personnel), approaching the E-3 draw at 0810 hours bore a horrific similarity to newsreels he had seen of the assault on Tarawa the previous November. In front of him were ‘landing craft on their sides, turned the wrong way. It was surreal. I joined that great pile of men on the shale. We were immobilised. I did not know what to do or where to go. I remember looking at the sea, there were bodies and equipment just rolling in the surf.’7 Their two assault companies were well and truly pinned down.

Shortly afterwards, Daniel L. Curatola had stepped off the Empire Anvil with the rest of the Third Battalion’s headquarters company: ‘I didn’t expect to live. All through Africa and Sicily, all the battles, guys dying around me, my friends, I thought sooner or later the law of averages was going to get me. What kept me going? Inside me, I had fear. But we were told we had to follow our orders. No matter whether your best friend or your brother gets killed, you’ve got to do your job. If you stopped when a guy was wounded, an officer would yell: “Take cover, don’t worry about that guy!”’8

Gefreiter Gockel’s water-cooled machine-gun was a heavy, cumbersome beast which put out a steady six hundred rounds a minute. Crouched behind it, traversing left and right on the tripod, the eighteen-year-old knew the trick was to go easy on the trigger – just five- or ten-round bursts. As long as he had enough water for the gun and 250-round canvas belts of ammunition, he could keep firing for a long time. However, soon after Gockel had begun, sand from nearby explosions jammed his gun. He paused, opened the gun and found the problem was dirt between the cartridges. ‘I laid some stick grenades on the sandbags and had my pistol ready for self-defence while I removed the ammunition belt, cleaned everything quickly and started shooting again, but my hands had been trembling,’ he recollected.9

Yards uphill to his right, Hein Severloh had an altogether more modern machine-gun, an MG-42 – this was the burrrrp gun that Sergeant Hyam Haas recollected. With its very high rate of fire, the drawback was that an MG-42 went through fifty-round belts like a knife through butter, and the barrel would overheat quickly, causing it to jam. When this happened, Severloh used one of two rifles in his bunker until it cooled down. Gockel, Severloh and their buddies opened fire at five hundred yards, the range narrowing to 150 as the tide drew in. Meanwhile, Obergefreiter Siegfried Kuska’s 50mm anti-tank gun facing east into the E-3 draw accounted for at least three Shermans. The position’s two 50mm mortars, each fired from inside a little concrete Tobruk bunker, in the hands of their expert two-man crews, were placing mortar bombs inside landing craft and on the sands at up to five hundred yards range.10

In the face of such concentrated fire, the previous battle experience of the Big Red One was vital. The extreme confusion they faced would have shredded more inexperienced units. ‘We had to keep moving,’ mused Curatola. ‘Thank God, I had seen dead men before, in Africa and Sicily. But some of the younger troops who hadn’t seen action just went out of their minds. You’d see them screaming and running the wrong way.’11 Captain Bill Friedman, the regimental S-1 [personnel officer] and a professional soldier with combat experience in North Africa, still had to control his own nerves. ‘At one point I was lying down and shouting in the ear of the Regimental S-4 [quartermaster], Major Leonard C. Godfray. My mouth was next to his ear; it was so noisy that he could not hear me otherwise. While I was trying to make myself understood above the din, a bullet struck him dead. It had hit him in the centre of his helmet. Our faces were inches away when it happened. It could have been me.’12

But what did being a veteran mean? Joe Argenzio – the sixteen-year-old who had lied about his age to enlist and had been dubbed ‘Baby Face’ as he walked up the gangway onto the Empire Anvil in Weymouth harbour – recalled, ‘a lieutenant gave me a carbine and some .30-cal ammo; that’s all I knew. As we approached the beach, I said to one fellow on my right, “Thank God I’m with you veterans.” He replied, “Kid, the minute the ramp drops, you’re going to be a veteran.”’13

Captain John G. Wilhelm Finke, commanding Company ‘F’, was one of the first officers ashore opposite the E-3 draw. The thirty-two-year-old, who had won a Distinguished Service Cross in Sicily, explained that once ashore, ‘we had difficulty getting the men to move. There was a great deal of enemy fire and they would take cover behind these obstacles, which were about the size of a ten- or twelve-foot telephone pole with a Teller mine [a flat, plate-sized anti-tank ordnance, one foot in diameter] on the top of it. The whole area was just full of these obstacles. People would just try to take cover behind one of these poles. Any port in a storm. Well, it didn’t provide any cover so you just had to force them to move no matter how you did it. It so happened that I had sprained my ankle in the marshalling area and had to go ashore carrying a cane instead of a rifle. I used it to very good effect to just whack people until they moved’ (an interesting image amid the confusion of Omaha).

The setback was immediately obvious enough for patrol craft PC-552, anchored offshore and monitoring proceedings, to radio back to USS Samuel Chase at 0641 hours, ominously: ‘Entire first wave foundered’. By 0830, the 7th Naval Beach Battalion’s beachmaster had ordered a temporary suspension of landings, and at 0945, for want of anything else to report, V Corps signalled to Bradley aboard USS Augusta the understatement of the morning: ‘Obstacles mined, progress slow, DD tanks for Fox Green swamped.’ Although the Big Red One had come through North Africa and Sicily, it had suffered considerable casualties. Consequently when they landed in Normandy their ranks included draftees, new to combat. However, it was noticeable how many officers and NCOs had survived the Mediterranean, and it was their leadership – if they survived – that provided the glue for unit cohesion during the first few hours.

‘Everybody had a heck of a large load to carry so that the men were worn out when they got across the sand,’ recalled Captain Finke. ‘We landed in an area that was right in the mouth of the beach exit, where all weapons were sited to fire. Of the four officers that were killed on the beach from my company, I think three of them died right at the water’s edge. Once you get involved in something like this, you’re thinking about what you have to do, and more or less forget about your own personal danger, because you don’t have time to think about it. The more you have to do, the better off you are in a situation like that. My company had lost all of its officers by the time I was wounded around noon.’14

Roger Hutchinson, with Company ‘C’ of the 299th Combat Engineers, distracted his buddies from their nerves and nausea by passing around a two-dollar bill for everyone in LCA-15 to autograph. It worked, as the entire boatload added their thirty signatures to the paper – but for a third of them, it would be the last time they would ever sign their name.15 A fellow engineer with Company ‘C’, Chuck Hurlbut – who had laughed at the name of their ship, the Princess Maud, in Weymouth harbour – remembered they were supposed to land on Easy Red, but their craft was pushed by the strong current to the next sector, Fox Green, just to the east of the Colleville draw.

‘Everything was nice and quiet,’ he recalled, ‘then all of a sudden, brrrrrr, ping, ping, ping – we could hear the bullets hitting the ramp. To my knowledge, we all got off OK. First thing I did was to take my rifle and aim it at a pillbox. Pow! I still don’t know why I did that. It was an impulse. That was the only shot I fired all day. I started pulling the rope of our raft full of explosives. All of a sudden I felt it get heavier. I looked around, and there’s three bodies inside, face down; I kept pulling, and all of a sudden, boom! A mortar round blew all our explosives. I was knocked head over heels, and blacked out. When I came to, I was on my hands and knees, spitting blood with the worst headache you can imagine. It took me a few moments to realise what happened. I pulled my rope in, and all I got was a big piece of tattered rubber. That was the raft. The three guys, gone.’16

Hurlbut’s buddy, Tom E. Legacy from Niagara Falls, had come up to him before disembarkation. ‘We’d been through a lot together. He opened his jacket. And he had on the ugliest, gaudiest, most outlandish necktie I ever saw in my life. We laughed about what we were going to do when we hit Paris. Later in the landing craft, amid the vomit and the spray, he flashed the necktie again, and I gave him a thumbs-up.’ Subsequently, when sheltering in the lee of the cliffs east of E-3, ‘about sixty yards away a guy wanders along the beach, staggering, floundering like he’s blind drunk. His backpack is tattered; his clothes are in shreds. One arm is dangling. He turns and half his head is blown away. And something told me I know that guy,’ recounted Hurlbut, ‘something about his stature, his walk. And he turned toward me and looked at me, and through all that gore and all that tattered clothing, I saw the tie. I wanted to cry out to him; I couldn’t. I didn’t have any voice. I was frozen. He just staggered away.’17

Just west of the Colleville draw, beaching his LCT on Easy Red, skipper Bill O’Neill remembered their sister craft LCT-540 withdrawing, her bow damaged so the ramp couldn’t be raised. Off to starboard, another of their flotilla, LCT-305, was under heavy shellfire, unloading some 741st Tank Battalion Shermans which raced off, firing. Beyond her, LCT-25 was about to disembark half-tracks of the 197th Anti-Aircraft Artillery Battalion, but the first was hit as it raced down the ramp, bursting into flames. ‘Instantaneously the rest of the craft and its contents blew up in a violent burst of exploding ammunition and fire’.

O’Neill recalled LCVPs quickly unloading and withdrawing. ‘One alongside us, with wood chips flying as bullets hit her hull, gunned out in reverse, zig-zagging wildly, its coxswain not bothering to wait for his deck hand to raise the ramp.’ O’Neill’s LCT-544 contained eight jeeps and a large Cat tractor towing steel tracks to lay on the sand. ‘The bow ramp was dropped with a splash, and without a moment’s hesitation the Cat with its blade elevated roared off, attracting every machine-gunner in range. Bullets showered on the blade from every direction.’18

One of the luckiest landing craft – which demonstrates well the random nature of the carnage – was LCT-199, which disembarked her load of half-tracks at 0845 hours on Easy Red. She withdrew and took in a second cargo of eighteen jeeps and three hundred GIs to the same destination at 1330.19 In the same 18th Flotilla, LCT-305 was as unlucky as LCT-199 was fortunate. As she approached Fox Green at 0900, her bridge was raked by crossfire from WN60 and WN61, wounding her skipper. Her crew pulled out and tried again five hundred yards west, but were directed away; again they retracted and tried beaching twice more. Afterwards, they transferred their wounded skipper to USS Ancon, obtained a replacement, but on their fifth attempt to land, LCT-305 detonated a mine, which ‘completely demolished the crew’s quarters’, so they withdrew rapidly. After six hours offshore, on their sixth beaching attempt at 1500, they at last disembarked all their anti-aircraft half-tracks, but hit an underwater obstacle retracting. Then they were struck by several shells, which killed one man and wounded the new skipper alongside seven others. LCT-305’s luck had run out, and she began to sink by the stern.20

The 299th Engineer Charles Hurlbut came across ‘one guy laying and moaning in the water, just being washed with the waves. I look at him. Jesus Christ, it’s one of my pals, Joe Nokovic of Buffalo, New York. If I leave him he’s gonna drown. I’m a little guy, and he was pretty big. I knew I could never lift him so I got my hands under his armpits, planted my feet in the sand and pulled with my arms. It was torturous, but we made progress, very slowly, to the dune line but I was exhausted. I was able finally to attract a medic; he took one look and gave him morphine. But I’d made the dunes in one piece, sat there and looked at all the chaos. Guys floating in the surf. The wounded screaming. Out in the water ships burning, smoking. I was numb. You thought you were tough, brave and gung-ho. This was not the way it was supposed to be.’21

All morning, GIs dragged their wounded to the waterline where landing craft could shuttle them back to the medical facilities of troopships offshore. Beaching at around 0730 hours, skipper Bill O’Neill’s LCT-544 survived almost four hours on Easy Red, taking on wounded all the time. ‘The living quarters were soon filled, then the inside spaces, then every available free spot on the deck,’ he recalled.

There was no end to the supply of blood-stained casualties. At 1130 hours the last few injured were rushed aboard, ramp raised, and using the engines and winch we slowly backed off into deep water, reaching the troopship anchorage, twelve miles out, in less than two hours. We let the larger ship’s trained medics take over, then cleansed our craft of all the discarded bandages, morphine capsules, bits of tissue and clothing. Crew bunks, mattresses, and blankets were soaked with blood. Everything was thrown overboard; the fire pump rigged, the ramp lowered, and the decks were flushed with seawater pushing everything into the sea, attempting to wash away the misery we had just witnessed.22

*

However, small bands of survivors were hitting back. Several men from Company ‘E’ of the 116th had gapped the concertina wire east of E-3 with Bangalores and pushed halfway up the bluffs. From there they took out one of WN61’s mortar pits with rifle grenades. Looking down, they witnessed a one-man frontal assault by Technical Sergeant Raymond F. Strojny, of Company ‘F’. This was John Finke’s company, but he was elsewhere on the sands. In the absence of his officers, Strojny first ordered his men into better cover. Then the resourceful twenty-six-year-old from Massachusetts, who had already won a Silver Star in Sicily, picked up a bazooka from a wounded soldier nearby; it had been pierced by shrapnel and should not have been fired. Tucking the weapon under his arms, with six bazooka rounds, he crawled through WN61’s protective minefield; the bodies of several GIs lay about as he wormed his way to the closest bunker.

Strojny’s first shots merely antagonised his opponents, who in return peppered the lone GI with machine-gun and sniper fire. One round pierced his helmet, grazed his skull and exited, but nothing more. With more bazooka rounds he destroyed the pillbox, actions that would bring him a Distinguished Service Cross, but, more importantly, two key parts of WN61 had been destroyed. Finally, its 88mm gun, which had engaged three 741st Shermans in quick succession, fell victim to a fourth – Staff Sergeant Turner Shepherd’s DD tank – which had swum ashore onto Fox Green after 0630. The Sherman managed to put several shots through the embrasure, killing the gun crew and damaging the weapon. WN61 was all but silenced. The operations log of the 352nd Division recorded baldly at 0720: ‘Landing of forces on beaches in front of WNs.60, 61 and 62, and further to the west. Between WN61 and WN62 American strength is one company on the beach, under fire from our own artillery. The 88mm in WN61 has been knocked out by a direct hit.’23

Across the way, the two west-facing 75mm guns of WN62 were doing brisk trade along Easy Red. However, one of the surviving 741st DD Shermans, commanded by Sergeant Geddes, had silenced the upper emplacement early in the morning, killing or wounding the gun crew of Gefreiters Lehrmann, Kriefteworth and Hans Selbach and Kanonier Emil Drews, all friends of Franz Gockel. The Sherman’s gunner was Jack Borman, whose tank later bogged down in the shingle mound before the entrance to the Colleville draw. This would act as an effective barrier to many tracked and wheeled vehicles until it could be bulldozed aside by engineers. ‘As we were immobilised, the crew then decided it would be better to remain completely impassive,’ Borman explained. ‘So the tank remained motionless and no one – from either one side or the other – took any serious notice of us. Only as darkness fell did we finally risk leaving the tank.’24

At 0725 hours, the duty officer of the 352nd Division noted in their log, ‘One company is attacking in front of WN60 and WN62. Four further boats have landed in front of WN61. One boat has been shot in flames by the 50mm gun [from WN62]. The Americans have penetrated WN62 and at the same time, WN61 is being attacked from the beach in front and the rear [Strojny and the 116th detachment]. Five minutes later the same source recorded “352nd Artillerie-Regiment had no connection to its observation post near Colleville [WN62]”.’25

At this point, Severloh remembered, two of his frightened colleagues ‘were sitting in a foxhole quite near me to the east. They kept loading their rifles, which they poked up over the wall of the trench and, without being able to see any target at all from their cover, simply fired.’ To his front, ‘Wounded moved around on the bloody, watery slime, mostly creeping, trying to get to the upper beach and find some cover behind the shingle embankment; one by one they would occasionally run in a crouch.’26

Down on the sands, hard on the heels of ‘E’ and ‘F’ came Company ‘H’, containing machine-gunner Valentine Miele – the Jersey City veteran of the Sicilian campaign. He recalled floating his tripod ashore, attached to a life preserver but having to ditch a box of ammunition just to stay afloat himself. His assistant gunner carried the actual gun tied to another life jacket. They lost men to drowning and bullets as the company waded ashore and reached the shingle mound. Then ‘some guy came running up and said “a machine-gun up there is cutting the hell out of Company G”. So my sergeant says, “Miele, get on the gun.” I set the gun up, and he says, “See if you can spot him.” All of a sudden I saw him, about two hundred yards away, and I’d say maybe thirty or forty feet higher than me. He wasn’t firing at me. He was firing down across. So when he opened up again, I picked him up, I got about ten rounds in there, and that sonofagun never fired any more.’27

An advance element of the 16th’s regimental headquarters had landed at 0720 hours, but was unable to function because all their communication equipment was either lost or destroyed by enemy action and key personnel killed, including the regimental executive officer, Lieutenant Colonel John ‘Huey’ Mathews. Leaving USS Charles Carroll, and steered in by coxswain Ricardo Feliciano, Colonel Taylor himself stepped ashore from LVCP-71 with the main body at 0820 on Easy Red, just to the right of the Colleville draw, and, in the words of the 16th’s After Action Report, ‘was immediately subjected to enemy artillery, machine-gun and small arms fire’.28 As Taylor later observed, ‘It was a helpless feeling wading while shot at.’ Private Warren Rulien, a member of the I&R (Intelligence and Reconnaissance) Platoon, remembered that his colonel had ‘laid down on his stomach and started crawling towards shore’, then overheard Taylor bellow to one of his staff, ‘If we’re going to die, let’s die up there, pointing at the bluffs.’29 Immediately Taylor noticed groups of his men, bunched up on the beach, cowering behind anything that seemed to offer shelter, as he had done, momentarily. Very much in the manner of ‘Dutch’ Cota and Charles Canham – and at about the same time – Taylor realised that he, personally, needed to instigate change by personal example.

Numerous eyewitnesses from the 29th Division recalled its Assistant Divisional Commander, Brigadier General Norman Cota (1893–1971) (left) and Colonel Charles Canham of the 116th Infantry (1901–63) (right, wearing spectacles), striding along the shingle of Dog and Easy sectors, urging men to grab their weapons and equipment and move inland. The 16th Infantry’s Colonel George Taylor (1899–1969) (centre, receiving medal) was responsible for rousing his men in a similar fashion around the E-3 draw. Taylor’s rallying cry has since become famous: ‘Two kinds of people are staying on this beach: the dead and those who are going to die – now let’s get the hell out of here!’ (both US Army Signal Corps)

The bland words of the regimental After Action Report, that ‘Reorganisation was instigated immediately by the Regimental Commander and the beaches were rapidly cleaned of personnel through the one gap available on Easy Red’, do not do Taylor justice.30 Under fire, Taylor rose to his feet and would remain upright for much of the rest of the day, striding purposefully through the shot and shell, rallying his men. His regimental surgeon, Major Charles E. Tegtmeyer, never forgot Taylor’s example: ‘He passed us walking erect, followed by his staff and yelled for me to bring my group along.’ Picking up Taylor’s cue, Tegtmeyer exclaimed to the medics around him, ‘I’ll be damned if I go back into that water even if Hitler himself should order me.’31

The magic spread: in full view of the defenders, Lieutenant Colonel Robert N. Skaggs of the 741st Tank Battalion stood on the beach, swinging his life jacket in the air to beckon his men, and ordered them check the weapons of every abandoned tank and get those that could be operated back in action. Somehow, German snipers were looking the other way. Three of Skaggs’ tank crewmen later recalled the breakdown of the remaining two members of their crew. ‘Coming in, Sergeant Holcombe was so shocked and would not give any order except, “Abandon tank!” The loader couldn’t load the gun so the bow gunner had to get in the turret to load the gun and command.’32

This was the context of Taylor’s oft-quoted words which have since become US Army shorthand for the leadership on Omaha Beach that morning: ‘Two kinds of people are staying on this beach: the dead and those who are going to die – now let’s get the hell out of here!’ It is a tribute to Taylor’s effectiveness that many claimed this order was directed at them. In reality, Taylor was everywhere with the same message, but word of his actions was also spreading among his men.33 Skaggs’ tankers were galvanised into action: ‘The tank was almost drowned out, we had to drain the water and dry the motor. We pushed up a bank of dirt to shield the infantry, shared our blankets with the wounded, and loaned them the tank’s machine-guns, to keep the snipers down while we were working.’34

Taylor’s encouragement was sorely needed; as Tegtmeyer recollected, ‘at the water’s edge, floating face downward with arched backs, were innumerable human forms eddying to and fro with each incoming wave, the water about them a muddy pink in color. Floating equipment of all types like flotsam and jetsam, rolled in the surf mingled with the bodies. Units of infantry and amphibious engineers were inextricably mixed together, officers without men and men without their officers, lay perplexed awaiting orders.’

Spurred on by his commander’s example, the surgeon soon established an aid post through which a succession of his friends passed.

This picture of Easy Red during the late afternoon of 6 June captures the chaos of the landings. The first barrage balloons are up. In the foreground and centre lie dead soldiers covered with blankets, tangles of German barbed wire, and a stranded LCVP from the attack transport USS Thurston. The GI (right) standing by the DUKW wears the insignia of the 1st Infantry Division. (NARA)

Major Dave McGovern, our Air-liaison Officer, had been hit and before I could ask him about his injury, he pointed upward to the planes flying overhead and said, ‘Look at them, you guys should be damn thankful they’re there.’ I agreed readily enough and he continued, ‘You guys said this would be rough, but God, I didn’t think it would be this rough. You guys can have my pay-and-a-half anytime.’ I admitted it had been rough, a hell of a lot rougher than Africa and Sicily, in fact rougher than anything I ever want to go through again. I examined his wound; it was a jagged shell fragment just to the left of the heart, and the fifth and sixth ribs were broken. I asked Dave if he wanted to be evacuated and he replied, ‘No’, he didn’t want morphine either, but he was having a helluva time getting a decent breath. Captain John Finke came in with a compound fracture of the right arm and a wound of the right leg, both wounds were already dressed, but he needed morphine.35

Captain Friedman, Taylor’s S-1, found his commander’s actions the spur he needed. First, he understood that he could not do anything to change his fate. Such an acceptance that he was probably going to die steadied his nerves and he could think calmly. Next – like Taylor – he needed to inspire those around him. Friedman came across three soldiers lying prone, rigid with fear as the bullets whipped all around them. Standing tall, he drew his pistol to urge them on. ‘I wanted them to go forward to attack, but one of them shouted at me, “Captain, are you out of your f**king mind?”’ Prodded, cajoled, threatened by pistols, whipped by canes or simply shamed by example, men began to move laterally to the bluffs, through gaps already blown in the wire – or blew some more.

Friedman remembered, ‘Once we got to the base of the bluffs we were relatively safe. We were quite well protected from view and from the enemy’s fire. I don’t think they expected anyone to get off the beach, because once we’d started moving up the hill and clearing their positions, it became just a matter of time. The positions really did not have any depth to them.’36

We last met Chaplain John G. Burkhalter – former Miami Baptist minister turned chaplain with the Big Red One – in southern England with his jeep, trailer, portable organ and song books. He was one of many who would write home – in his case to his wife Mabel – recalling how his colonel had ‘stood on the beach where thousands of men were pinned down by enemy fire, and in a quiet drawl said, “Gentlemen, we are being killed here on the beaches; let’s move inland and be killed there.”’

As far as Burkhalter was concerned, this was the pivotal moment when everything changed.

In from the beach were high hills which we had to climb. We crawled most of the way up. As we filed by those awful scenes going up the hill and moving inland, I prayed hard for those suffering men, scattered here and there and seemingly everywhere … We filed over the hill as shells were falling on the beach back of us, meaning death for others who were still coming in. Before going over the top of the hill we crouched for a while close to the ground just below the top. While lying there I did most of my praying. The shells were falling all around and how I knew that God alone was able to keep them away from us. I shall never forget those moments. I am sure that during that time I was drawn very close to God.37

First Lieutenant Quentin Murdock in regimental headquarters was another inspired by his colonel. The Idaho farmboy had returned from the Mediterranean with a Silver Star – and malaria. He was incensed as military doctors instructed him to sit out the invasion. ‘The 16th’s surgeon and I argued back and forth about it. He finally relented and gave me some quinine. I guess he thought I was crazy.’ This was a surprisingly frequent occurrence within the Big Red One and 2nd Armored Divisions from their service in the mosquito-ridden wastelands of North Africa and Sicily. Triggered by bites from European bugs, the illness reappeared and caused twenty per cent of US Army non-battle casualties in the Normandy campaign.

Of the journey to the shore Murdock remembered, ‘One minute you’d be up on top of the waves and you could see all the ships firing. The next minute you’d be way down in a valley of water.’ He crawled ashore with the second wave, and lay on the sands ‘for a bit, maybe twenty minutes, trying to get my mind together again’. He explained: ‘There was so much enemy fire and you couldn’t do anything. It was demoralising how bad it was. Then Taylor came along; was hitting everybody on their rears to get over the hill. It shook us out of the daze we were in and got us going.’38

Also moving about the men, getting them to collect their weapons and move through the gaps, was Brigadier General Wyman. He had arrived about 0800 hours, immediately sized up the situation, and sent a signal to the effect, ‘Halt all vehicles, send only infantry reinforcements.’ This was extremely timely and resulted in the 18th Infantry arriving on Easy Red in time to assault the E-1 Saint-Laurent draw. Wyman’s deployment of his reserve was done at the appropriate moment and in the correct spot. Unlike Generalleutnant Dietrich Kraiss, he had made the right decision, but his contribution tends to get squeezed out of the standard histories, in favour of the more charismatic combat leadership of Taylor.

One of the assault wave soldiers with the 16th Infantry was T-5 (Technician, Fifth Grade) and radio man John J. ‘Joe’ Pinder, of Headquarters Company. He was a very gutsy, determined one-year combat veteran from the Mediterranean – and a pre-war professional baseball player. Pinder hailed from McKees Rocks, Pennsylvania, but the family moved around the state to wherever work could be found. Described in 1941 as ‘the stocky, square-set little Pennsylvanian with the blinding fast ball’, he had entered military service in 1942. For Pinder, 6 June was a special day – he shared a birthday with one-legged General Erich Marcks, and Frau Lucie Rommel, and had just turned thirty-two.

During the run-in Pinder’s craft was hit and began to sink, but made it to the beach. He was clipped by two bullets as he reached the sand, but three times returned to find more radio equipment and code books. This time a burst of machine-gun fire caught him as he struggled to the shingle. It was his last journey: he dumped his equipment with the rest, set up his radios, but soon passed out from loss of blood, dying later that morning. Maybe Pinder’s activities didn’t stand out in the collective memory in the way Taylor’s did – but soldiers remembered, and a year later Pinder would be awarded a posthumous Medal of Honor.

By about 0900, irrespective of the urgings of Taylor, Canham and Cota, perhaps five hundred GIs in small groups, often undirected, had made multiple penetrations all along the front. In the absence of officers and NCOs, life’s natural leaders had bubbled to the surface – reflected by the 235 Medals of Honor, Distinguished Service Crosses or Navy Crosses awarded on D-Day.39 Independently they reached the heights and were beginning to mop up some of the defenders’ positions. However, it would take hours for this news to filter back to the senior commanders nervously waiting offshore.

Landing with the last wave of the 16th Infantry was Captain ‘Hank’ Hangsterfer, HQ Company commander with the First Battalion. He noted,

as we got in view of the shore, some of the landing craft from the first wave were returning to the transports. They waved to us; we waved back just like you would do on a pleasure boat ride. As we approached the beach I could see the water obstacles still in place. It appeared to be high tide so it was perilous trying to land. When the ramp was lowered the troops ran off in a hurry, but not before we were raked with machine-gun fire which hit a few men. There were so many troops on the beach it was difficult to find a space to take cover from the enemy small arms fire.

On the beach I saw Bob Capa, the combat photographer, taking pictures of the carnage. He was behind one of the self-propelled guns [DD tanks] which had been knocked out.

The two had previously met in Sicily and knew one another slightly. ‘There was one path through the barbed wire which led to what appeared to be a swamp. However, it was over waist deep so the troops had to hold their rifles overhead. On the hill up the ridge was evidence of the price that was paid. Dead bodies either shot or blown up by personnel mines. It’s hard to express the feeling I had when I saw the dead soldiers I knew, ones I’d seen in training.’40

‘The coast of Normandy was still miles away when the first unmistakable popping reached our listening ears. We ducked down in the puky water in the bottom of the barge and ceased to watch the approaching coastline,’ wrote the man responsible for some of the defining, grainy, fuzzy images of D-Day – breathing movement, drama and also fear. He was Endre Friedmann, a Jew forced to flee his native Hungary, later Berlin and ultimately his beloved France. His life seemed to be a tale of staying one step ahead of Fascism, but staying close enough to turn and photograph it. Reinventing himself as Robert Capa in 1930s Paris – his sought-after American citizenship would be bestowed in 1946 – he had risen to fame photographing a soldier at the moment of death during the Spanish Civil War. Capa’s images began to be published around the world, and by 1944, in his thirtieth year, he was a regular freelancer for Life and Collier’s. Present for many of the iconic moments of the Second World War, including the invasion of Sicily, it would be unthinkable for him to miss D-Day – and so it proved. Aboard the Samuel Chase, he had chewed over with Colonel Taylor – whom he also knew from Sicily – with whom he should land. Taylor offered him space in his own boat, but as Capa later explained, ‘I was a gambler. I decided to go in with Company ‘E’ in the first wave.’41

‘There was too much going on to be afraid,’ remembered Gefreiter Franz Gockel of being in WN62. He knew every inch of the beach, and every obstacle because he had spent the previous few months putting them there, never believing he would one day be spraying the area with fire. His position overlooked their anti-tank ditch and ‘tangle-foot’ barbed wire entanglements, which resembled ‘exposed tree roots’, pegged out at ankle-level and designed to trap advancing infantry. He was also equipped with two automatic flamethrowers which at the flick of a switch could project fire onto anything – or anyone – attempting to cross. The controls were in Gockel’s dugout. Through the morning, he watched the tide coming in, drowning the wounded and pushing the survivors closer towards him. He recollected after the smaller craft, a bigger landing boat came in as the waters rose [LCI-554 ramming its way through the obstacles at around 1000 hours] from which scores of men exited down ramps on both sides.

‘One comrade who was about fifty yards forward of me crawled back to my dugout. Achtung, Franz! They’re much closer. Now we really have to defend ourselves.’ His buddy fed the canvas belts into the gun, while Gockel quartered the weapon back and forth, but shortly afterwards this ‘there was a massive splitting noise and the gun was torn from my hands; it was shot to pieces. The water-cooled barrel had been split open by a piece of shrapnel, and it is still hard for me to imagine how I survived the blast without a wound. At the same moment a grenade hit one of the flamethrowers near to me. It exploded, leaving only a few wires where it had once been.’42

This may have been the handiwork of Staff Sergeant Walter Skiba’s tank from Company ‘A’ of the 741st, which, ‘from our defiladed position behind the shingle, fired on several machine-gun nests from which fire was visible, then picked up a log emplacement and fired several rounds of 75mm at it, before a shell landed quite close, and Skiba was killed almost immediately’.43

‘My beautiful France looked sordid and uninviting, and a German machine-gun, spitting bullets around the barge, fully spoiled my return,’ wrote Capa of landing with the 16th Infantry. ‘I paused for a moment on the gangplank to take my first real picture of the invasion. The boatswain, who was in an understandable hurry to get the hell out of there, mistook my picture-taking attitude for explicable hesitation, and helped me make up my mind with a well-aimed kick in the rear.’ Capa had been covering war since he had first gone to Spain in 1936, and was certainly no coward, but this was not the invasion he had expected, observing:

The bullets tore holes in the water around me, and I made for the nearest steel obstacle. A soldier got there at the same time, and for a few minutes we shared its cover. He took the waterproofing off his rifle and began to shoot without much aiming at the smoke-hidden beach. The sound of his rifle gave him enough courage to move forward and he left the obstacle to me. It was a foot larger now, and I felt safe enough to take pictures of the other guys hiding just like I was.44

Leaving his now useless machine-gun, Gockel and his wounded comrade crawled through their zig-zag trenches uphill, but as they did Gockel felt a violent blow to his left hand: the Americans were close at hand. ‘When I looked, my mitt was covered in blood and three of my fingers were dangling from their tendons. But for me it was a million-dollar shot – it meant I could leave the battlefield.’45 As he hurried away he dropped some of his possessions, but with several other wounded grenadiers commandeered a horse and cart and headed into Bayeux, where their wounds were patched up. Incredibly, the Big Red One’s Joint Assault Signal Company (JASCO) lineman, Patrick J. Hughes, later picked up a pocket-sized German Bible and kept it as a souvenir of his service in Normandy. Inside the cover was written one name – Franz Gockel.46

‘I finished my pictures and the sea was cold in my trousers,’ wrote Capa. ‘Reluctantly, I tried to move away from my steel pole, but the bullets chased me back every time. Now the Germans played on all their instruments, and I could not find any holes between the shells and the bullets that blocked the last twenty-five yards to the beach,’ explained the photographer in his 1947 autobiography, Slightly Out of Focus. Reaching the sand, he threw himself flat and his lips touched the earth of France. ‘I had no desire to kiss it. I didn’t dare to take my eyes off the finder of my Contax and frantically shot frame after frame. Half a minute later, my camera jammed – my roll was finished. I reached in my bag for a new roll, and my wet, shaking hands ruined the roll before I could insert it in my camera. The empty camera trembled in my hands.’

Then Capa with remarkable honesty relates what many soldiers – grizzled old veterans and greenhorns alike – must have been feeling that morning on Omaha. He writes of ‘a new kind of fear shaking my body from toe to hair, and twisting my face. An LCI braved the fire and medics with red crosses painted on their helmets poured from it. I just stood up and ran toward the boat. I stepped into the sea between two bodies and the water reached to my neck. I held my camera high above my head, and suddenly I knew that I was running away.’47

Hein Severloh in his artillery observation post had also been hit – physically. He recollected, ‘There was a bright, loud report directly in front of me. Something flew at me from the muzzle of my machine-gun, and it was as though I had been hit in the face with a whip under my right eye. I noticed the front sight was missing from my gun.’ By now he had fired over ten thousand rounds from his MG-42, and was obliged to switch to tracer, used for night firing. This allowed him to correct his aim, but gave his position away at the same time: soon afterwards a shell landed directly in front of his post, then a second tore his gun away, with a third and fourth arriving in very quick succession.

Robert Capa knew he was doing what none of the troops on Omaha could do that morning – simply leave when he felt like it. He boarded the LCI, which, he explained, ‘was listing, and we slowly pulled away from the beach to try and reach the mother ship before we sank. I went down to the engine room, dried my hands, and put fresh films in both cameras. I got up on deck again in time to take one last picture of the smoke-covered beach.’ Further away from danger, his sense of profession reasserted itself and he

took some shots of the crew giving transfusions on the open deck. An invasion barge came alongside and took us off the sinking boat. The transfer of the badly wounded on the heavy seas was a difficult business. I took no more pictures. I was busy lifting stretchers. The barge brought us to the USS Chase, the last wave of the 16th Infantry was just being lowered, but the decks were already full with returning wounded and dead. This was my last chance to return to the beach. I did not go.48

Oberleutnant Frerking had been directing fire from his inland battery until it ran out of ammunition. Incredibly, only two weeks earlier half their ammunition stocks had been moved back to a more secure arsenal. When he requested more from his battalion commander, Major Werner Pluskat – who had much earlier spotted the invasion fleet from his command bunker – Frerking was initially told it was on its way. Later he was informed that no shells would arrive: an Allied fighter had pounced on the truck and destroyed it.

Soon, Frerking and Severloh realised that they had been outflanked and a strong force of American troops – Company ‘G’ of the 16th – were attacking from the west (today’s car park and Visitor Center for the US cemetery). It was time to leave. Frerking ordered the last rounds from his battery down on their own position. Outside, his colleague Leutnant Grass, a former NCO who had been using rifle grenades with great effect throughout the day, Platoon Leader Feldwebel Pieh and radio men Herbert Schulz and Kurt Wernecke queued up to make their escape. Bullets whipped past. ‘You go next, Hein – take care,’ Frerking said to Severloh. ‘He addressed me with the familiar “du” for the first time. We didn’t have time to say much more.’49 Severloh ducked and dived his way to safety. He looked back. Frerking, Grass and Pieh had not followed. It was 1530 hours; WN62, the strongest resistance nest behind Omaha, had fallen.

Safely back on USS Samuel Chase, Robert Capa fell asleep, exhausted. He arrived back in England and sent his film up to London. ‘Seven days later’, he recorded, ‘I learned that the pictures I had taken on Easy Red were the best of the invasion. But the excited darkroom assistant, while drying the negatives, had turned on too much heat and the emulsions had melted and run down before the eyes of the London office. Out of the hundred and six pictures in all, only eight were salvaged. The captions under the heat-blurred pictures read that Capa’s hands were badly shaking.’50 This was the 19 June edition of Life, one of its most famous. In fact eleven were salvaged and ever since, no news feature of D-Day is complete without one of Capa’s ‘magnificent eleven’ images.

And yet … and yet … Capa’s narrative and photographs have excited the imagination down to the present day; given the quality of the ‘magnificent eleven’, made more dramatic by their rescue, the world has wondered what the rest might have contained. Robert Capa was certainly there on Easy Red – if not quite in the first wave with Company ‘E’: there are too many troops and tanks already ashore in his images to have been at the tip of the spear, and in his own text, he wrote of ‘The first empty barge, which had already unloaded its troops on the beach, passed us on the way back to the Chase and the Negro boatswain gave us a happy grin and the V sign. It was now light enough to start taking pictures, and I brought my first Contax camera out of its waterproof oilskin.’51

He probably arrived with Taylor’s headquarters group around 0820 to 0830 hours. Had he landed opposite the Colleville draw with Company ‘E’, Capa might not have survived. Fortunately, he landed further west, where there was less incoming fire, in the area overlooked by the American cemetery today. Close examination of his images shows four tanks and many troops of the earlier waves ahead of him, milling about on the beach, some standing. When pointing his camera seaward, his images of men clustered around the beach obstacles, often interpreted as using them for cover, are in fact of engineers with the 5th Engineer Special Brigade, wiring them up for demolition. Capa seems to have spent between thirty minutes to an hour on Easy Red – not long, but brave for anyone without a weapon – where he saw and waved to Captain Hangsterfer, before boarding LCI-94. This vessel also contained a US Coast Guard photographer, David T. Ruley, and the latter’s film recorded the return of LCI-94 to the Samuel Chase and the transfer of casualties, and contains glimpses of Capa helping with the wounded. Yet their LCI, though damaged, was not listing or sinking.

However, another vessel nearby was, which, holed by numerous shells and listing badly, limped back to the Chase and would later capsize. This was LCI-85, and it seemed that Capa borrowed the drama and fate of the latter vessel for his own narrative. This false note has triggered much research which now suggests that Capa suffered a real breakdown on Easy Red, as he started to recount, and that the extremely traumatic morning resulted in him being able to take no more than the few images developed.52

Sometime afterwards he also wrote privately to friends in the USA of ‘saltwater contaminating his film’, so he knew that not all the images would survive. The world-famous story of the incompetent or overexcited darkroom assistant was an ingenious camouflage to mask his sudden breakdown. After eight years of covering war at close quarters, it is not unreasonable to observe that Robert Capa may indeed have been suffering from PTSD, though he would very soon return to Normandy and produce many more fine pictures of the campaign. However, the camouflage was unnecessary: the surviving images delivered the goods and none of this lessens the man, or his photographs – in fact, it makes him more human. One’s respect for the photographer braving fire on Omaha beach, armed only with a camera knows no bounds, but is a lesson for historians in accepting received wisdoms at face value.53

General Bradley, aboard the Augusta, had been biting his nails all morning, first at the lack of news, then because the reports were growing worse. For the first few hours offshore, he had as little to go on as Gerow and Huebner on board USS Ancon, but as early as 0913 hours, the First Army commander had already pessimistically signalled Ramsay and SHAEF, ‘Opposition Omaha considerable. If required, can US forces be accepted through Jig and King [sectors of Gold Beach, sixteen miles to the east]? Most immediate. Pass to GOC 21st AG [Montgomery].’ It is illustrative of the mass of paper flying around that morning that Bradley’s missive was not read until the afternoon, by which time the crisis had passed – but such a move would surely have been interpreted in terms of a Gallipolian disaster. Even sending the signal would have involved much eating of humble pie on Bradley’s part, with issues of national pride at stake – made worse by Montgomery’s own inclination to gloat over American mishaps whenever given the opportunity.

Information famine is an affliction that bedevils every military headquarters in war, and the usual solution is to go see for yourself. Bradley despatched his twenty-seven-year-old aide, Major Chester ‘Chet’ B. Hansen, along with Kirk’s gunnery officer, to cruise along the shore and report what they could see. They returned at the end of an hour with depressing news. Along Fox, in the Big Red One’s sector, few channels had been opened through the obstacles, causing craft to divert to Easy Red, where more gaps had been blown, but this in turn was leading to congestion as the tide crept in.

At noon, V Corps was forced to admit, ‘Situation critical at all four exits.’ The time lag between achievement and reporting was abysmally slow. If by 0900 maybe five hundred men had landed safely in every sector of the beach, negotiated their way through the minefields, climbed the bluffs and in small groups were moving inland, by midday this figure had climbed to something like five thousand, with much of the 18th and 115th Infantry Regiments ashore and forging onwards.

However, V Corps were not in a position to confirm these first flickers of success until 1309 hours, when they informed Bradley, ‘Troops formerly pinned down on Easy Red, Easy Green, Fox Red, advancing up heights behind beaches.’54 Bradley recorded these moments in his 1951 memoir A Soldier’s Story, though many of the words were actually Hansen’s. The stocky, pink-cheeked and baby-faced former journalist had kept a meticulous diary and ghost-wrote much of the book for his general.55 The seemingly strong German dam at Omaha had been breached, and with the Americans pouring through, in the words of another historian, ‘nothing short of a panzer division could plug that hole now’.56

Originally there had been no plan to capture the little track that led towards Cabourg, five hundred yards east of E-3. It was more of a notch in the cliffs with a gentle scramble up to the top, rather than the broad winding valleys, sloping gently uphill, that characterised the rest of the draws. It worried the Germans sufficiently to site the last of the resistance nests overlooking Omaha, WN60, at its head, comprising several concrete gun emplacements. On the beach below, most of Company ‘L’, 16th Regiment, had landed half an hour late, at 0700, never intending to attack this feature. They had been pushed east, away from E-3, where they’d intended to land. Likewise Company ‘I’, some of whom had drifted off course as far as Port-en-Bessin – as much a navigational error as the fault of the current – and would return to land in the vicinity of F-1, but at 0800, one and a half hours behind schedule.

At this stage the destroyers offshore had realised the very tenuous hold Taylor’s regiment had on the coast of France, and USS Doyle had started to close with fire support. Company ‘L’s commander, Captain John R. Armellino, remembered, ‘straightaway one of my landing craft was swamped by the violent seas and sank. To this day, I don’t know how many of those men were lost.’ Closing fast, his men, too, encountered the eerie ‘silence on the way to the beach. You could hear a pin drop. We didn’t know what to expect when we landed. We soon found out. About a quarter-mile from the beach, all hell broke loose.’57

With the incoming tide, the waters had closed to three hundred yards, and most German attention in the two positions that could see Fox sector, WN60 and WN62, was focused away to the west, on the Colleville draw. Thus, Company ‘L’ made it across the sands in a matter of a few minutes, though losing twenty-seven men to machine-gun fire. ‘I lost many of those young soldiers who joined my company right before the invasion in England,’ reported Armellino. ‘They had no fear, and failed to hit the ground after every few yards, instead running directly for cover. The more seasoned men hit the ground very often, and as a result avoided being hit by enemy fire.’ However, Armellino himself became one of those casualties, injured by a mortar bomb.58

One of a sequence of images taken at the foot of the cliffs on Fox Red sector during the morning. It shows seven dead GIs washed ashore, probably from the 16th Infantry. The thin line of darker shingle suggests the tide is just on the ebb, implying the time is about 1130 hours. The fact that the fallen are covered with clothing, life preservers and, in one case, a cardboard box, suggests they have been badly disfigured by gunfire rather than drowned. (US Army Signal Corps)

Company ‘L’ Sergeant Mike McKinney – ‘the lucky Irishman from Brooklyn’ and pre-war soldier seasoned in the Mediterranean whom we have met already – recalled, ‘we just sort of flopped down. Caught our breath. I’m looking around to see who’s with us, see what kind of help we’ve got. Who made it to the shore? Do we have the satchel charges? Do we have the flamethrower? We had the flamethrower. We had the satchel charges and the Bangalores. And we had a few guys from the 116th Infantry; these strangers showed up and said, “We don’t know where to go,” so I said, “Stay with us.” I knew they were supposed to be down the beach a little further, but I didn’t know what they were supposed to do. So we made riflemen out of them, and put them along the waterline and had them start shooting at a pillbox, to close up the apertures.’59

By this time, two of the 741st’s Shermans had arrived and were led by Lieutenant Jimmie W. Monteith on foot through a minefield, to fire positions that would best help suppress the German strongpoint. Needing to destroy the troublesome WN60 before they could do anything else, the unplanned assault by Company ‘L’ up what would become known as the F-1 draw evolved, despite their captain’s wounding. Monteith led one of the assault sections through the wire and minefields, while other sections crept up the draw using ground which offered a covered approach from the strongpoint. Sergeant Hugh Martin recalled that Monteith ‘paid no attention to the shells and machine-gun fire when he went to the wire and afterwards led us through the minefields’.

They outflanked it, entered the outlying trenches, and mopped up with grenades and satchel charges. By 0900 hours, Company ‘L’ was able to signal Third Battalion headquarters that WN60 had been captured and they were pushing on to the high ground east of the Colleville draw. Reinforcing success, a heavy machine-gun section from Company ‘M’ and another section from Company ‘K’ had also joined them, but at around ten a counter-attack infiltrated the Company ‘L’ advance, during which Monteith was killed. Armellino would recommend him for a Distinguished Service Cross; Bradley and Bedell Smith concurred. However, Eisenhower took one look at the citation and mused, ‘Looks like a Medal of Honor to me. This man was good.’ Thus Monteith became the fourth and last recipient of the supreme honour, awarded for actions on D-Day itself.60

Control of the high ground east of the E-3 draw was key to its eventual capture, thus the peripheral action of the Cabourg draw would prove central to the opening of what became the key exit off the beach. Although three Company ‘L’ men were captured and spent the night in Cabourg, the next morning PFC Lawrence Mielender would return with fifty-two prisoners.61 This was the first substantial penetration of the Omaha defences in the eastern sector, and happened at about the same time Captain Goranson’s Ranger company beyond Vierville in the west were also making their way up a shallow gully – and penetrating the maze of WN73.

Another image taken at the foot of the cliffs at Fox Red sector during the morning of 6 June. Protected from fire, several wounded GIs have gathered to await medical evacuation. The two on the right wear the badge of the 29th Division on their left sleeves. They are from Easy Company of the 116th Infantry, who were swept miles east from the rest of their formation. The others are with the 16th Infantry of the Big Red One. (US Army Signal Corps)

Towards the end of the day, Chuck Hurlbut, the Company ‘C’ 299th Engineer, was clearing obstacles at the eastern end between the E-3 and F-1 draws. ‘I had lost my rifle; the thought in my mind was – army discipline: “I’m going to catch hell.”’ He started looking for one. ‘There were hundreds of them, laying all over. I picked one that looked pretty good. Later, up on the bluffs our officers told us, “We’ve taken a pretty bad beating. We’ll talk about it in the morning. Tonight just try to dig in up here. Stay close.” So we went and dug a foxhole and lay down, but you couldn’t sleep, because the infantry and tanks was still moving up. Down on the beach, they were still unloading stuff. You were so excited and revved up that you couldn’t sleep,’ explained Hurlbut. ‘You learned an awful lot in those hours, realised that, hey, this is not a game. A lot of the craziness, the gung-ho attitude disappeared. It hit you that so many of your buddies were no longer with you.’62

Captain James Milnor Roberts, aide to General Gerow, crossed the Channel on the attack transport Charles Carroll before transferring to an LCVP. Approaching Easy Red at 1700 hours, he remembered his craft being hit with artillery fire about a hundred yards out. ‘It was like a summer thunderstorm; a few drops at first, then everything all at once. Only this was lead. Fragments were knocking us around; several people were hit, including the skipper who was killed. It is very difficult to dig a hole in a steel deck, but there isn’t much cover on a Higgins boat. I recall mass confusion and fear; frankly I was in a panic,’ Roberts admitted later. He disembarked in chest-deep water and climbed the bluffs to Saint-Laurent under shell and sniper fire; at the top he looked back: ‘It was just fantastic; vessels of all kinds as far as you could see.’

Roberts set up V Corps HQ just north of Saint-Laurent, ready for Gerow’s arrival at around 2100 hours. The general’s priorities were communications and the possibility of an armoured counter-attack. There was no contact with either flanking formation – the British 50th Division at Gold, or VII Corps at Utah – if the Germans counter-attacked in the night, V Corps would be on its own. As darkness fell, Roberts broke out his K-rations and ate his first meal of the day. ‘Around midnight when things seemed to be fairly quiet, I remember thinking – Man, what a day this has been. If every day is going to be as bad as this, I’ll never survive the war.’63

Landing with the reserve regiment, Colonel Jeff Seitz’s 26th Infantry, was Major Donald E. Rivette of Dearborn, Michigan, XO of its anti-tank company. He had been one of the first soldiers in the 502nd Parachute Infantry, but had broken his leg during training and wound up with the 26th instead. Rivette spent his D-Day waiting to land. Early in the morning, he remembered,

the clam doors of our LST opened and three DUKWs carrying 105mm howitzers slid into the stormy seas. They hadn’t gone fifty yards when each floundered and sank. No more disembarked for over an hour, waiting for the sea to subside. By about 0930 hours when it had calmed a bit, several more were launched: these seemed to stay afloat. At 1000 we saw a destroyer charging past us, firing several shells at the cliffs, but our LST was five miles out and too far away to make out what was happening.64

It must have been mid-morning when Rivette observed a German fighter shot down. Two Focke-Wulf 190s flown by Oberstleutnant Josef ‘Pips’ Priller and his wingman, Feldwebel Heinz Wodarczyk, had earlier made a low pass over Omaha from the direction of Gold Beach and, despite the torrent of anti-aircraft artillery thrown against them, had survived. Priller, already a renowned ace, who would eventually chalk up 101 victories in 1,307 combat missions, was based in Lille. Considered the leading Luftwaffe ‘expert’ on the Channel Front, he had just sent some of his pilots to Biarritz for a week’s leave and had ordered others to move inland on 5 June, to Reims and Nancy; their ground echelons were still on the road on 6 June.

Priller’s sortie is well known through being recounted in The Longest Day, though other Luftwaffe flyers in Fw 190s were active over the beachhead area – but failed to return – at least one hundred missions being recorded during the day. Rivette remembered the moment the German aircraft crashed: ‘every soldier and sailor seemed to stand up and cheer as in a football stadium’. As the day wore on, he recounted how ‘First Division Headquarters warned us around midday we had troops ashore but they had not broken out, so our landing was pushed back. Initially it was 1300, afterwards 1600 hours, then postponed. In fact some of the 26th did land on the sixth; but I had to wait till dawn on 7 June, landing just opposite the large draw on Easy Red.’65

Once ashore, Rivette noted

tanks and other vehicles stuck in the sand or destroyed by mines or gunfire. Other debris including hedgehogs, barbed wire, wrecked landing craft and all sorts of equipment littered the beach. I saw eight or ten wounded enemy prisoners, waiting for attention in the battalion aid station: they had an oriental look about them; it turned out they were recruited from somewhere in Russia. The Graves Registration units had been busy throughout the night and bodies were piled in neat rows like cordwood: it looked like we had lost half the assault wave.66

By the end of the day, the casualties suffered by Taylor’s 16th Infantry were broadly similar to those of Canham 116th’s, the After Action Report noting thirty-six officers and 935, killed, wounded and missing.67 This formed the bulk of the Big Red One’s losses for D-Day, estimated at 1,036; 29th Division losses at 743; and V Corps’, including the Rangers, at 441. The 741st Tank Battalion’s operations log noted ‘laagering in a field two miles from the water and watching a canopy of red tracers slice the air overhead to drive off Luftwaffe raiders’. Their first tank status report, submitted to V Corps at 2315 hours on 6 June, indicated that it had precisely three battle-ready Shermans, two damaged but repairable, and forty-eight reckoned lost. ‘Working through the night, salvage and repair operations would succeed in getting the damaged armour operational, so that on the morning of 7 June the battalion could field a provisional platoon of five tanks ready for action.’68

Hyam Haas, whose anti-aircraft half-tracks had silenced the WN65 bunker, remembered afterwards driving up

to the top of the bluffs and soon the sounds of battle began to recede from our area and we began to breathe a little freer. We were off the beach and the sun came out and warmed us. We were soaking wet most of the day and now we began to dry. At that position we sort of recuperated from the trauma of the landings. We had lots of ground coffee and we kept a pot on our stove – we even gave passing generals coffee. We stayed on the top of the bluff, a sort of plateau, where an airfield was built.69

Indeed, many GIs would recall the buzz of aircraft taking off and landing as they landed on Omaha after D-Day. The airfield was a 3,400-foot-long by 120-foot-wide strip of bulldozed earth, opened for aircraft within forty-eight hours. Soon it was handling P-38s and C-47s, flying casualties back to England. Long since returned to nature, the airstrip overlooked the beach and was on the heights immediately west of WN65 and east of the Les Moulins draw.

Today, Omaha is much as it once was; the obstacles are long gone, as are the mines and barbed wire. Much of the shingle mound was bulldozed aside by engineers to facilitate access off the sands, and the holiday villas have been rebuilt. Rommel’s Atlantikwall proved more difficult to remove, so nearly all of it remains in situ, enabling the keen historian to interpret every battlefield action. A counterpart to the Blue and Gray memorial on top of the WN72 bunker at Vierville is the Big Red One’s memorial obelisk atop the WN62 strongpoint dominating the Colleville draw. It overlooks the beach Easy Red and Fox Green sectors where the 16th, 18th and 26th Infantry Regiments landed, and commemorates by name those in the 1st Infantry Division killed in the Normandy battles from 6 June to 24 July, when the breakout began. Similar pillars track the division’s progress all the way to Cheb, on the Czech-German frontier.

The polished granite obelisk, like a sundial, lies at the heart of WN62, once occupied by Gefreiters Hein Severloh and Franz Gockel and Oberleutnant Bernhard Frerking. Their mortar pits, gun emplacements and the observation post from which Frerking and Severloh fought the invasion are still present, as are the zig-zag trenches – now shallow depressions in the ground – through which Severloh and Gockel made their escape, and Frerking did not. A walk onto the forward slope brings the visitor to the 5th Engineer Special Brigade Memorial, mounted on top of the upper 75mm gun emplacement, knocked out by Sergeant Geddes’ DD tank.

The shallow scars in the concrete of this and the lower 75mm bunker illustrate how difficult these structures were to defeat. A commemorative stone acknowledging the service of the counterpart 6th Engineer Special Brigade, whose commander, Colonel Paul W. Thompson, was wounded during the day, sits in the Vierville draw. Both brigades were huge organisations, formed especially for D-Day, and each comprised around a dozen battalions of engineers and quartermaster, medical, ordnance, port and naval beach staff. The fairly intact strongpoints of WN61 and WN60, beyond to the east, also repay a visit, though they sit on private land.

To the west lies the Colleville American military cemetery, where the first fallen warriors arrived in November 1948. They came from temporary burial sites established throughout Normandy, where the dead of all nationalities had been laid to rest together, in carefully recorded plots. Two were within the confines of Omaha Beach, one at Utah, and a further pair at Sainte-Mère-Église. Once American service personnel were removed to Colleville, some of these other sites would be taken over by the Germans as permanent graveyards for their own war dead. At La Cambe, for example – originally known as the 29th Division’s cemetery – 4,534 Americans were buried alongside 8,574 Germans. Now La Cambe has become the principal site for the commemoration of 21,222 soldiers, mostly from the Seventh Army, including Hein Severloh’s boss, Oberleutnant Bernard Frerking. Orglandes and Marigny are two further examples of German burial sites that were originally US Army graveyards. Among the former’s 10,152 graves is that of Generalleutnant Wilhelm Falley. The Marigny site, near Saint-Lô, commemorates 11,172 soldiers, including the one-legged General Erich Marcks who celebrated his last birthday on 6 June 1944.

The village of La Cambe, home to fewer than seven hundred souls in June 1944, rapidly became known as ‘Little America’. Besides the cemetery, four field hospitals, two airfields, a petrol depot and an assembly workshop for GMC trucks were established in the vicinity, the latter employing 150 locals. Similar Allied infrastructure existed all over Normandy in 1944–5, employing tens of thousands of French men and women. At La Cambe, 6×6 ‘Jimmy’ trucks were assembled from parts shipped over in wooden crates and processed through Omaha Beach. At peak efficiency they turned out up to sixty 6×6 trucks a day; a similar depot at Isigny producing as many as one hundred jeeps in the same timeframe, which were also parked at La Cambe, causing an American war correspondent to label the area ‘Mini Detroit’. Pierre Darondel remembered the moment some GIs came to his farm at La Cambe and offered their jeep in exchange for a bottle of Calvados. Darondel refused the deal, pointing out the hundreds of jeeps parked behind his house.70

The task of honouring the dead was mammoth: by the end of the war, the Army Graves Registration Service and the Burial and Registration Command had identified 206,577 American personnel killed in Europe, of whom 76,360 lay in twenty-four temporary cemeteries in France, sixteen of them within the duchy of Normandy. In 1947, families were offered repatriation of their loved ones and within a year 34,874 of America’s fallen had returned home. From 1948 onwards, the remainder who served in northern France were concentrated at Colleville – and a second site on the Normandy–Brittany border at Saint-James, and today 9,387 Americans, including three servicewomen, are interred in the 172-acre Colleville plot under the Normandy sun. One of the women was 27-year-old American Red Cross volunteer Elizabeth A. Richardson from Indiana, who died in an air crash. We have met her already, handing out doughnuts and coffee from her Clubmobile in southern England.

A further 1,557 individuals, who were never recovered or could not be identified, have their names inscribed on the walls of a semi-circular garden on the east side. This is why Captain Taylor N. Fellers is buried in Bedford cemetery, Virginia, Private Bedford T. Hoback has a grave at Colleville, but his brother Staff Sergeant Raymond S. Hoback is commemorated on the wall of the missing.

Eighty miles to the west, in a further twenty-eight acres of French earth, the less well-known Saint-James American cemetery contains the remains of 4,410 US servicemen who lost their lives fighting in the later breakout battles, including ninety-five headstones of unidentified GIs, and the names of 498 of the missing – a small rosette device helpfully marking those since recovered and identified. Its lookout tower gives a panorama of their battlefields and Mont-Saint-Michel. It also marks the point where American forces exited the hedgerow country of Normandy and entered the plains of Brittany during the offensive around Avranches. Saint-James also contains a famous 29er – Pennsylvanian Staff Sergeant Sherwood H. Hallman, who landed on D-Day with Company ‘F’ of the 175th Infantry and was awarded a Medal of Honor for his bravery on 13 September, only to be killed by a sniper the following day.