32

Juno: Maple Leaf at War

‘I remember a bulldozer to the right of us on the beach. It was pushing landing craft out when their ramps had got stuck in the sand. Suddenly it hit a mine and went spinning up into the air.’

Landing craft coxswain at Courseulles, Juno Beach1

As at Omaha and Gold, but not Utah, the Canadian Major General Rod Keller would be hurling two brigade groups at the Normandy coast, deploying the maximum combat power that his shipping would allow. The central focus of his attack would be Courseulles, astride the River Seulles. This was an important location, less because of its small harbour and more because it controlled access across the river, which in German hands would impede any link-up with the British 50th Division to the west.

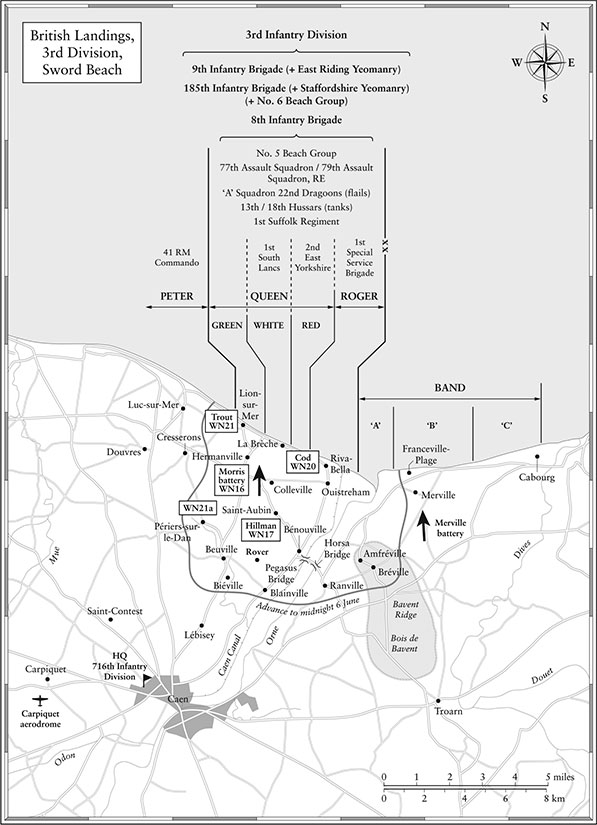

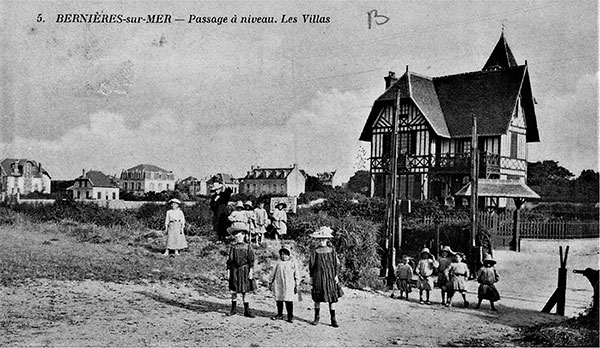

Its port was man-made, the Seulles snaking round to the west, but was tidal and unusable for some of each day. The little harbour was one reason for the narrow-gauge railway that ran along the coast from Ouistreham – goods unloaded at Courseulles could be sent around the region at speed. From the sea, the town’s appearance was different to that of Asnelles and Ver to the west or Bernières and Saint-Aubin to the east: Courseulles was a working fishing port, not a tourist centre, and possessed no promenade, beach wall or smart seafront housing. This necessitated the Organisation Todt building their bunkers on the beach itself, where they were very obvious to an attacker.

The Germans understood the importance of the small fishing town equally well, and were concerned that the gap in the offshore reefs opposite the river mouth seemed to beg for Allied attention. Securing the western flank of Courseulles – also marking the extreme western boundary of Juno – on a slight ridge inland and overlooking Mike Green sector (which was not assaulted), lay strongpoint WN33a. Anchored between the settlements of Vaux and Graye-sur-Mer, this was the headquarters of the 1st Company of the 441st Ost-Bataillon, and hosted a 75mm gun. Some of the 7th Company of the 736th Grenadier-Regiment also lodged here, but much of this unit’s attention was directed westwards, for they were also responsible for the defences at La Rivière that did so much to hold up the 69th Brigade of the 50th Division.

It is perhaps worth emphasising that the Germans would have had no comprehension of the separate beach landings; on 6 June the defenders were simply aware of attacks all along the coast. While we look back with hindsight at the beaches codenamed Omaha to Sword, this knowledge was of course denied to the Germans – and indeed to the wider world at the time. To Generals Marcks, Kraiss and Richter in their various headquarters, the realisation of the separate divisions, and therefore defined beaches with operational boundaries, only came when they started capturing maps and taking and interrogating prisoners. Of course, such knowledge would have helped the Germans immeasurably. For they merely needed to surround each individual beachhead, aware that in the first few hours they were all acutely vulnerable and each fighting their own battles for survival.

Across the meandering Seulles river was Stützpuntkte-Courseulles, collectively the strongest position on the invasion coast after those at Omaha. Commanded by Hauptmann Grote of the 6th Company, 736th Grenadier-Regiment, it comprised three resistance nests, one either side of the river and a third to the south. WN31, commanded by Grote on the western bank, was fronted by a minefield, overwatched by three 50mm guns in various emplacements and a 75mm field gun in a thick concrete casemate in enfilade facing west, plus machine-guns and mortars. On the opposite (eastern) bank lay WN29, led by his second in command, Oberleutnant Herbert Hallbaur, sporting both an impressive anti-tank wall to the front and a ditch to the rear, an 88mm in a reinforced concrete blockhouse facing east, and – five hundred yards away – two 75mm cannon, one German, the other French, in eastwards-facing bunkers, one 50mm (which remains on the harbour wall to this day, its gun shield pierced by tank fire), a 37mm in a Renault tank turret, and several machine-guns. As we have seen, these employed a wide range of different ammunition, much of it from French and Russian stocks. The 88mm – decidedly German – would, until silenced, also cause trouble further down the coast for the attackers on Nan White at Bernières. The WN30 depth position inland consisted of machine-guns and mortars in field positions.

With Courseulles the object of an H-Hour assault by the 7th Canadian Brigade, a mile to the east, the 8th Canuck Brigade would launch themselves at the two seaside settlements of Bernières and, a further mile beyond, Saint-Aubin. Bernières was one of the oldest settlements on the Côte de Nacre, with Roman origins and its twelfth-century Romanesque church built on land belonging to Bishop Odo, William the Conqueror’s half-brother. Its street plan had evolved in the days of oxen and carts, and had not progressed much since, offering a potential bottleneck to any invader, and a gift to the defenders. A more modern twelve-foot sea wall lined some of the beachfront at Saint-Aubin, on top of which ran a road, overlooked by many brick-and-mortar houses, shops, hotels and restaurants. These had all closed and their occupants evacuated.

Commanding the 5th Company of the 736th Grenadier-Regiment, Hauptmann Rudolf Grüter at Bernières – Nan White sector to the Canadians, WN28 to the Germans – had a wide frontage to cover. He was protected to the front by minefields and to the rear by an anti-vehicle ditch south of the railway line. Scheduled for assault by the Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada, the defences were in reality a reinforced platoon-sized location of several concrete positions housing single 75mm and 50mm guns, a tank turret, six machine-guns and three mortars, placed to dominate the exits from the beach. Grüter’s second in command, Oberleutnant Gustav Pflocksch, oversaw WN27, the defences at the western end of Saint-Aubin, where the Germans had demolished most of the buildings to create fields of fire for a 50mm and several machine-guns. This was Nan Red, attacked by the North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment.

Immediately after the invasion, a special observer team assessed the Saint-Aubin defences in terms that applied equally to many of the other Juno and Gold positions:

Several houses had all windows and openings to seaward bricked up. Some had sandbags beneath first floor windows to provide cover for snipers. Elaborate and very strong reinforced concrete portions housing the main weapons and command posts were constructed, with walls and roofs estimated to be three-to-five-foot thick. Shelters with eight-inch concrete slabs covered with masonry and earth were provided, with exceptional command of the beach. In general the defences consisted of a series of earthen strongpoints from which machine-guns could be sited, linked by an intricate and extensive system of communication trenches. Numerous mortar positions existed consisting of concrete chambers with magazines attached built flush with the land [Tobruks]. All defences were blended in with the general character of the locality. Wire was used extensively along the seawall and around areas marked as Mines.2

At Saint-Aubin, all these defensive works have long been swept away in the name of tourism, save for one prominent bunker built into the sea wall, which still houses its 50mm anti-tank gun, the muzzle damaged on D-Day.

Langrune, a smaller seaside village, and virtually a continuation of Saint-Aubin, likewise had a twenty-foot-high sea wall and in appearance and architecture was not dissimilar to Saint-Aubin. Its WN26 strongpoint consisted of half a dozen machine-gun nests, two mortars and a 50mm gun emplacement, mostly set in the coastal wall and surrounded by mines and wire. With a concrete anti-tank wall, ten feet high and four feet deep, barring access from the eastern edge of the beach, its arcs of fire were integrated with those of Saint-Aubin to the west and Luc-sur-Mer in the east. WN26’s defenders were based on the 9th Company of the 736th Grenadier-Regiment, led by Hauptmann Kurt Mickish and his second in command, Oberleutnant Herbert Wlost, who were also responsible for WN24 and WN25 at Luc-sur-Mer. Langrune stood on the boundary between Juno and Sword and was not attacked from the sea, but assaulted by 48 Commando coming from the west. The larger plan was for 41 Commando to land on Sword, proceed west and link up with their 48 Commando brethren, thus closing the gap between the two beaches.

These six strongpoints in the four towns comprising Juno Beach were manned by little more than four companies (about a battalion’s worth) of men with five field guns, nine anti-tank cannon, seven mortars and around forty machine-guns – but this amounted to well under half the density of Omaha’s defences – and nothing like enough to face six well-trained infantry and two tank battalions. Most German crew-served weapons were sited to create a killing zone along the shore. Once inland, attackers would have an easier time because these positions were sited too far apart to support one another. Preregistered artillery zones offshore were code-named ‘Köln’ – all an observer had to do was correct the fall of shot by degrees or metres.

Yet of all this weaponry, it was the relentless arrival of 81mm and 50mm mortar bombs throughout the day that would cause the most casualties. The instance of sudden death or injury, launched from an unknown position, also dented morale, and until the hinterland was cleared would continue to act as a nuisance factor. To the uninitiated – especially landing craft crews and beach group personnel – mortar fire was often misreported as artillery, leading to the initial and erroneous assumption that the Germans had deployed more field guns than was actually the case. All these positions were fronted by the usual rows of beach obstacles, often armed; other coastal weapons included a few electrically operated static flamethrowers – of the type Franz Gockel had at Omaha – none of which came into action on the day. An occasional log shelter also held a miniature Goliath tank, of the kind we first encountered at Utah. None would be deployed on account of the severing of their command wires, or demise of their operators.

The object of the 3rd Canadian Division, Juno Beach, extended immediately east of Ver-sur-Mer for six miles via the port of Courseulles to Saint-Aubin. Following on from Jig and King, allotted to 50th Division, Juno encompassed Love, Mike and Nan sectors. Love would not be assaulted but was reserved for the later offloading of equipment and stores. Mike, subdivided into Green and Red – west of the River Seulles – would be attacked by the 7th Canadian Infantry Brigade. Everything east of the Seulles, including Nan Green, White and Red, as far as Bernières and Saint-Aubin, was scheduled for invasion by the 8th Canadian Brigade. Additionally, 48 Royal Marine Commando would land at Saint-Aubin for their sally to Langrune-sur-Mer.

The 3rd Canadian Division’s forty-four-year-old Major General Rod Keller was actually English-born, from Gloucestershire; he migrated with his family when young and had been commissioned into the Princess Patricia’s Canadian Light Infantry at the end of the First World War. Attending the British Staff College at Camberley, he took command of his regiment in 1941. Keller had been promoted very quickly to lead the 1st Infantry Brigade a few months later, and within a year had taken over the 3rd Canadian Division. This was too rapid in the eyes of some, who expressed doubts about his suitability for such an important command.3 However, the Canadian Army General Staff was fishing from a very small pond for its senior personnel and Keller was popular with his troops, who appreciated his legendary bluntness.

His 3rd Division traced its roots back to the formation that had fought in the First World War, had been disbanded afterwards, then to be re-formed in 1940. With the 1st Canadian Infantry Division fighting in Italy and the 2nd badly mauled at Dieppe and still recovering its strength and confidence, the 3rd was the obvious choice as an assault division for Overlord. After its performance in Exercise Spartan, Keller was informed of their role on 3 July 1943. They had thus spent a year in preparation, concluding with Exercise Fabius III in May. Keller’s objectives were to reach the line of the Caen–Bayeux Route National, code-named ‘Oak’ – via two preliminary phase lines, ‘Yew’ and ‘Elm’ – capture Carpiquet airfield to the west of Caen, and link up with the British 3rd and 50th Divisions. It was Keller who had ensured that his division was the most motorised of all to land on D-Day; all his field regiments of artillery were fully self-propelled using American 105mm ‘Priests’, and most of his anti-tank units employed the US-designed, -tracked and -turreted M10, rather than towed weapons.

His formation would land in two brigade groups. Courseulles was Brigadier Harry Wickwire Foster’s 7th Brigade Group’s territory. Foster had already fought in the Pacific under the Americans and would go on to command two Canadian divisions. Somewhat the opposite to his divisional commander, Foster was bullish and self-confident, loathed paperwork and directed in a hands-off manner – much appreciated by his officers. His group attacked with two battalions up, the Royal Winnipeg Rifles tackling the western Mike Red and Green beaches, with the Regina Rifles – who hailed from Saskatchewan – to the east of the Seulles, on Nan Green. The Canadian Scottish – his third infantry battalion, recruited in Victoria, British Columbia – would follow behind the Winnipegs, the whole attack being supported by artillery field regiments, and engineer companies. The two attacking battalions would be supported by tanks of the Ontario-based 1st Hussars, a unit of Brigadier Robert A. Wyman’s 2nd Canadian Armoured Brigade; Wyman had joined Keller with the experience of handling the 1st Armoured Brigade in Sicily.

To their left, in the east, Brigadier Kenneth G. Blackader’s 8th Brigade Group would storm ashore on Nan White and Red – Bernières and Saint-Aubin. Older than Keller and Foster, Blackader had been wounded and won a Military Cross during the First World War, and by 1938 was commanding the Black Watch of Canada. He oversaw the assault from the frigate HMS Waveney, outfitted as a headquarters ship, from which he had led the pre-invasion exercises in April and May. In reserve, Keller had Brigadier Douglas G. Cunningham’s 9th Brigade to deploy where he thought best. Extraordinarily bright, and whose memory and meticulous attention to detail were legendary, Cunningham was a reservist and prominent barrister in Kingston, Ontario, who would eventually become commandant of the Royal Military College before returning to his legal practice.

In addition to his fifteen-thousand-strong division, Keller had been loaned from the British 26th and 80th Assault Squadrons, Royal Engineers, equipped with their Churchill AVREs; eleven Sherman flail tanks from ‘B’ Squadron, 22nd Dragoons, and nine of ‘A’ Squadron, the Westminster Dragoons; Centaur tanks with 95mm guns from the 2nd Royal Marine Armoured Support Regiment; the armoured cars of ‘C’ Squadron, the Inns of Court Regiment; as well as having 48 Royal Marine Commando under command. The Canadians also had the services of No. 7 Beach Group, built around the 8th King’s Regiment for Mike sector, and No. 8, including the 5th Royal Berkshires, for Nan sector. Bizarrely, the latter had no connection with the rolling acres of the Thames valley, recruiting instead in north-east London and known as the Hackney Pals battalion. Both these beach groups were similar in size and organisation to those employed on Gold and Sword. Collectively, these units amounted to a further nine thousand Britons under Canadian command.

Force ‘J’ had received their orders to set sail within fifteen minutes of Eisenhower’s decision to ‘Go’, made at Southwick House. ‘Church services held on practically all craft,’ noted one war diary; ‘More ships than a leopard with measles,’ noted another. Weighing anchor late on 5 June, and preceded by sixteen RCN minesweepers led by HMCS Caraquet, the armada followed a channel marked to port and starboard by small illuminated buoys dropped by the sweepers. It had already been decided – due to some of the Calvados reefs offshore – to make H-Hour later on Juno, with split timings. Landing in the west on Mike and Nan Green sectors, 7th Canadian Brigade would disembark at 0735 hours. In the East, 8th Brigade would assault Nan White and Red ten minutes later at 0745. During the night, however, the atrocious weather had slowed down the Force ‘J’ assault convoys and some had strayed off course. The conditions prompted Commodore Oliver and Major General Keller aboard their headquarters vessel HMS Hilary to delay H-Hour for the two brigades by a further ten minutes, to 0745 and 0755 hours, respectively. As the Royal Winnipeg Rifles set off from their mother ships for their ‘six miles of hell’ to shore, Private Hamilton noted ‘Rifleman [Andrew G.] Mutch, who was, as we all were, very, very seasick. He was lying on the gunwale and about two miles offshore, a large wave washed him off, and he went down. We never saw him again.’4

A larger-than-life Briton was one of the first figures many Canadians would have met on Juno. As chief beachmaster, Captain Colin Maud, RN, was perhaps the most prominent of his ilk. A veteran of Dunkirk, Narvik, the hunt for the Bismarck, and Malta and Arctic convoys, he ‘was fearless to the point of scorn of hostile shellfire’, a necessary characteristic for any beachmaster, who had to operate not just on D-Day, but for weeks afterwards. Described as ‘one of the most popular officers in the British Navy’, Maud is another character handed down to posterity by director Darryl F. Zanuck’s movie version of The Longest Day, where he was played by the British actor Kenneth More. Maud was the real deal: an eccentric naval officer, once encountered, never forgotten. With his heavy black beard, looking not unlike a pirate, he strode around Juno Beach, his commanding presence emphasised by his German Shepherd called ‘Winnie’ (translated into a bulldog for the movie) held on a tight leash, and shillelagh – a blackthorn stick. Maud, an advisor on Zanuck’s film, lent More the same stick he had carried on D-Day. The ‘props’ and bluster concealed an inner calm: Maud had earlier in the war been rescued from the waves after the torpedoing of his destroyer.

Leaving their moorings in the Solent the previous evening, the first Canadians touched Norman sand at 0749 hours. They arrived with the LCOCUs, with whom Royal Marine Sergeant Keith Briggs served. He recalled swimming out ‘with wires, ropes and hawsers to attach to obstacles so the armoured bulldozer drivers at the other end could clear a gap. Whilst we were working in the water it was mostly snipers who were our biggest problem. They were in the houses above us, sniping all the time. We didn’t let them frighten us and carried on and did our job.’5

When the rising water temporarily obliged them to abandon this work, Briggs and his colleagues attached lifelines from the shore to landing craft, allowing troops wading through the surf to cling to a rope rather than be washed away. Right across Juno, all were delayed by the appalling weather, some witnesses recording even brief rain squalls. Those awake and on deck marvelled at the sight of the midget submarine X-20, at sea since 2 June, which had surfaced at 0400 hours and was guiding Force ‘J’ to its anchorage, with her eighteen-foot-high navigation mast showing a bright light to seaward; she flew additional large flags after dawn.

As the German defenders woke up to the threat offshore, the future novelist Douglas Reeman noted,

Tall waterspouts shot towards the sky and then drifted down again very slowly. Lines of red and green tracer ripped across the water and were answered immediately by the destroyers and gunboats. There was a sigh as one of the smaller landing craft came to a dead stop with smoke pouring from her box-like hull as she began to heel over. The soldiers were swarming up and away from the sea, and I saw a motor launch speeding towards her to take them off before they were flung into the water. Weighted down with their weapons and ammunition, steel helmets and heavy boots, they would not stand much of a chance. Another of them was hit, vivid blobs of tracer licking out from the shore in straight, lethal lines.6

In the west, ‘B’ and ‘D’ Companies of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles left their landing ships, Canterbury and Laird’s Isle, aboard LCAs which took them to Mike Green sector at Courseulles, under heavy fire for much of their final approach. Well ahead of their DD tanks, their war diary noted, ‘The bombardment having failed to kill a single German, or silence one weapon, these companies had to storm their positions “cold” and did so without hesitation.’7 A Royal Navy report later concluded that of 106 itemised German positions targeted by the fleet, only fourteen per cent were disabled by naval gunfire.

‘The first Tommies jumped into the sea, which was quite shallow’, noted the teenaged Grenadier Hans Weiner of the first few minutes from his position at WN31. ‘The bullets hit them and their boats to good effect and I was a little surprised to see them falling – I don’t know why. Never having been in a battle before, it did shake me to be hurting those men, although they were enemies. Even then in my naivety, I thought that I was only hurting them. There was so much fire going at them I was surprised to see any survive. Tanks began shooting at us and we were forced to get down. Part of our blockhouse collapsed and we thought we would be buried alive. Then we ran out of ammunition so it seemed the sensible thing to surrender.’8

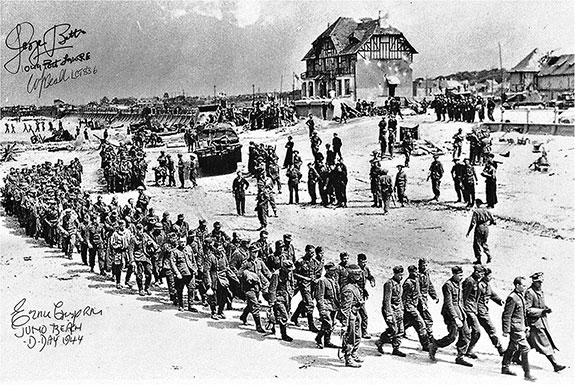

Men of the Royal Winnipeg Rifles of the 7th Canadian Brigade are seen heading to Mike Red beach at Courseulles in the opening hour of the assault. Their mother ship is often claimed to be HMCS Prince David, but careful research reveals she is the converted liner HMS Llangibby Castle, which carried 1,500 men to Juno, but lost ten of her fourteen LCAs in the process. As with many units, the ‘Pegs’ found themselves split between several landing ships, including the SS Canterbury and HMS Laird’s Isle. (NARA)

Captain Phil Gower of ‘B’ Company kept up a relentless pressure on the defenders, urging his men forward all the while; some recalled him taking off his helmet and waving it to show there was nothing to fear.

Clearing the beach obstructions, the 6th Field Company, Royal Canadian Engineers, as well as the Winnipegs suffered very heavy casualties. The engineers started the day with one hundred men, but would number just twenty-six by nightfall. One Winnipeg casualty was Corporal Walter J. Klos, nicknamed ‘Bull’ due to his huge physique, who though wounded in the legs and stomach still managed to crawl his way into a machine-gun nest and despatch two of his opponents before he succumbed. He was found inert, his hands still gripping the throat of one of his victims. Another was Sergeant Cosy, who with fifteen men charged another casemate and subdued it with grenades and machine-gun fire, but Cosy had been hit in the lungs and died on the spot. The bunker, recognisable by its extreme tilt, the foundations having eroded with time, is today known as Cosy’s Pillbox.

However, such bravery left Captain Gower with just twenty-six out of the 119 men with whom he had started. Many of his soldiers were old sweats, and though they had volunteered four years earlier, this was their first taste of battle. The sight of old friends felled in the initial seconds of their first combat was acutely traumatic. As they took the brunt of the fire, on their left, ‘D’ Company under Major Lockie R. Fulton cleared paths through the minefields and headed inland for Graye-sur-Mer, followed by ‘A’ and ‘C’ Companies and battalion headquarters.

By this time Lieutenant ‘Red’ Goff’s troop of Shermans from ‘A’ Squadron of the 1st Hussars had launched from LCTs of the 4th Flotilla, swam ashore and started taking on the pillboxes. Earlier in the landing craft, the Winnipegs had exchanged banter – one faux British accent shouted, ‘I say, old chaps, anyone for tennis?’ in the moments before landing.9 As one of the Hussar tanks was hit and its crew shot and machine-gunned as they bailed out, the message was immediately clear. This was no tennis match. Later the Winnpegs’ CO, Lieutenant Colonel John M. Meldram, praised the Hussars’ ‘gallantry, skill and cool daring in coming to the assistance of the battalion time and again, without thought of their own safety or state of fatigue’.10

Offshore, from the safety of his MGB, Douglas Reeman watched the armour land:

I found I could hardly breathe as the ramp crashed down and after the merest hesitation the leading tank rumbled onto the sand. Then there were others, huddled together, or so it seemed, as fire raked the beach and some of the running khaki figures fell down and stayed down. All along the beach the vehicles were rolling ashore. Some were hit, or crawled like blinded beasts with a track shot away. Like many of the little warships, we held station on the army’s flank, firing at anything which moved, until our minds were blank to everything else and our guns jammed from overheating. It was like a great tidal wave. Nothing could stop it as the army with infantry and sappers, stretcher-bearers and mine-detectors charged after the tanks … there was no recognition of time. It just went on and on, as if the vast panorama of battle was too great to ignore.11

For the assault, Brigadier Foster’s third battalion, the Canadian Scottish Regiment – or ‘Can Scots’ – was split. Major D. G. Crofton’s ‘C’ Company landed in LCAs from SS Ulster Monarch and under command of the Winnipegs. Their task was to destroy the 75mm gun at WN33a, west of Courseulles. Finding the fleet had managed this first, Lieutenant Roger Schjelderup’s platoon moved on, overwhelming three machine-gun nests in succession, taking fifteen prisoners. One of them was persuaded to lead them through his protective minefield, which opened the way for the rest of ‘C’ Company to follow, advancing in tactical formations through fields of tall, ripening wheat. It took some time to persuade the Germans in the vicinity – in fact mostly Russians from the 441st Ost-Bataillon – to surrender at the Château Vaux and Graye-sur-Mer, which both fell at a similar hour. The rest of the Can Scots arrived at 0830 hours with bicycles – many of them were photographed struggling ashore with their unwieldy iron steeds, issued to enable them to dash inland. By the end of the day only nineteen out of forty-five in Schjelderup’s platoon were still on their feet, the officer himself being wounded. A natural leader from a family of Norwegian immigrants, whose father had fought for Canada in the First World War, Schjelderup would soon return to battle, having earned a Military Cross for his exploits on D-Day. He would go on to win a DSO and a second MC and retire as a full colonel.

Each of the assault battalions relied on the intimate support of a regiment (a battalion in US terminology) of Royal Canadian Artillery, usually equipped with twenty-four 105mm M7 ‘Priest’ self-propelled guns. These had blazed away from their landing craft during the approach and once landed would aid the infantry’s advance, as directed by the Forward Observation Officers (FOOs). Unfortunately supporting fire was not always available, due to heavy casualties in the ranks of their eyes – the FOOs and FOBs, their naval observation opposite numbers. When the 12th RCA landed west of the River Seulles at 0830 hours, the timetable had slipped so much because of the weather that there was nowhere for them to go but line up on the beach and train their guns inland. However, this prevented their sister 13th RCA from landing at all, the latter circling uselessly in LCTs until the beach cleared sufficiently for them to land at 1500.

Major Mike Morrison with ‘A’ Company, 8th King’s Regiment, landed on Mike sector, as part of No. 7 Beach Group. He recalled: ‘The sea was very rough with troughs so deep that our assault craft appeared to be the only one around – and there were hundreds. A craft to my left was blown sky high, but we manoeuvred through the gap it created. I was first off and disappeared in nine feet of water. No one followed me.’12 This beach group included Royal Canadian Navy Volunteer Reservists who had trained as commandos; one of these was W. K. ‘Bill’ Newell, who served in ‘W’ Commando, the only Canadian beach commando unit, comprising three troops of three officers and twenty-five men each.

He landed on Mike Red and recalled,

we were set up to organise and control the flow of vehicles, men and supplies onto and through Juno beach on D-Day. The water was cluttered with the debris of combat from German bombing, strafing and shelling, but wreckage of landing craft and armoured vehicles were impediments to be avoided until conditions permitted their salvage. There were German prisoners gathered on the beach and many of them had soiled field dressings on their wounds. I spent much of my time guiding in tank and assault landing craft, unloading Shermans and Churchills, retrieving bodies floating in on high tides and generally doing what had to be done to help keep the operation moving. The first day I found a vacant enemy bunker in the sand dunes behind the beach which was close enough for me to use for short naps during any lapse in the traffic. I was taken aback to find twelve German army blankets for a bed and a large picture pinned on the sand bags of Betty Grable taking a bath; I had stumbled into a luxury suite.13

With seven succumbing to the waves, twelve 1st Hussars’ tanks managed to swim ashore after the Winnipegs. As soon as the major weapons had been silenced, ‘A’ Squadron were able to trundle up and down the sands engaging machine-gun nests, allowing the ‘Pegs’ to disengage and push inland. There were delays while assault engineers forced exits through the dunes but by 0920 hours the Hussars with the Winnipegs were on their way towards Graye-sur-Mer. The engineers were from the British 26th Assault Squadron, which had arrived between eight and eight-thirty. Split into two troops, they included ten AVREs, two BARVs (Beach Armoured Recovery Vehicles) and four D7 armoured bulldozers. Accompanying them were nine flail tanks of the 22nd Dragoons, whose 1st Troop leader, Lieutenant Ian C. Hammerton, had been amused to find his Canadian colleagues trimming their hair to Mohican style before they left Lymington.14

The assault engineers’ commander, Major Tony Younger, was particularly aware of the exit from Mike Red sector being blocked by a large water-filled crater, twenty yards long and three yards deep. With much dirt and weeds floating on the surface giving it the appearance of solid ground, the leading Churchill AVRE, call sign ‘One Charlie’, mistakenly drove into it. All six crew members escaped but afterwards came under mortar fire, which killed four and wounded the remaining pair. The vehicle’s own fascine was pushed forward of the tank and an assault bridge placed over it, effectively spanning the crater. By 1000 hours vehicles were driving over ‘One Charlie’ and the crater was further filled with rubble. The assault bridge was later replaced with another structure, named ‘Pont AVRE’, and crossed over time by King George VI, Winston Churchill and Général de Gaulle. It was only in 1976 that ‘One Charlie’ was remembered, recovered, restored and repainted, and it now stands close to where it disappeared from view in 1944. Of the many pieces of restored hardware scattered across Normandy today, ‘One Charlie’ is one of the few genuine D-Day relics.

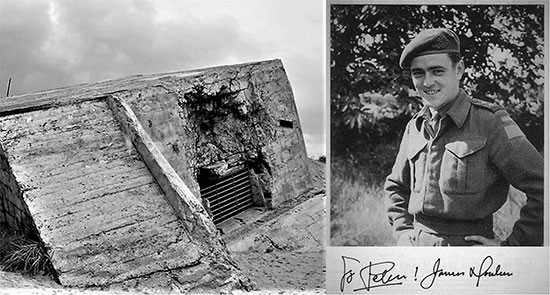

Another D-Day ‘relic’ who had an enduring presence afterwards was Lieutenant James M. Doohan of the 13th RCA. After a breathless and nerve-wracking D-Day, at around midnight the Command Post Officer of the 22nd Battery had been too slow with a password when challenged by a highly strung sentry armed with a Bren gun. Of the six bullets that hit Doohan, one struck a cigarette case, rather than entering his chest, but four rounds passed into a leg and one severed a finger. Evacuated to England, Doohan’s war, for which he had trained since 1940, had lasted precisely twenty-four hours. He was just one example of the multitude of casualties from ‘friendly fire’, an affliction that continues to dog modern warfare. Doohan would later find fame as Montgomery ‘Scotty’ Scott, Captain Kirk’s dour engineering officer, highly protective of his vessel’s engines, aboard the starship Enterprise. In the alternate 1960s universe of television’s Star Trek, the careful eye will detect that Scotty’s right hand – missing the finger – was invariably concealed on screen.

However, the trials of the 13th RCA or 26th Assault Squadron were as nothing compared to the British Inns of Court Regiment, a Territorial Army unit of reservists recruited from the professional classes of central London. Their thirty armoured and scout cars from ‘C’ Squadron, plus a headquarters group in twelve half-tracks, started to beach early on 6 June as their chaplain, Reverend John de Boulay Lance, remembered: ‘I was asked by the Colonel to land with “C” Squadron. The Royal Army Chaplain’s Department thought otherwise and ordered me to stay in England. Rather than find myself at the centre of a row I told some fibs and went,’ recorded the future Archdeacon of Wells. ‘Our craft struck two mines, which caused some minor casualties and one scout car damaged. The vehicle, parked just over the explosion, was mine and I was sitting on top of it. It did not harm me, but the suspension was ruined. There was nothing for it, and I watched thousands of pounds’ worth of armoured vehicle being tipped into the sea.’ The task of Lance’s beefed-up squadron was to dash ahead of the Canadians, circle round Caen and destroy bridges over the Orne or, failing that, the structures spanning the River Odon instead – hare-brained in the extreme and excessively dangerous.

Leaning at a surreal angle as the sea erodes its foundations, the pillbox (left) subdued by Sergeant Cosy of the Winnipegs remains in the sand dunes west of Courseulles. From 1500 hours on D-Day, the vicinity also saw the deployment of the 13th Field Regiment, Royal Canadian Artillery, with their 105mm self-propelled ‘Priests’. The Command Post Officer of 22nd Battery was wounded by a nervous sentry the same night. That officer was Lieutenant James Montgomery Doohan (right), who lost a finger in the mishap. He later found fame as Scotty, the engineering officer aboard the starship Enterprise. (Author’s collection)

Their good fortune was that they failed to even make it out of the Juno beachhead, for the Inns of Court would most certainly have been annihilated by the 12th SS or 21st Panzer Divisions racing towards the invasion. The Reverend Lance grabbed his ‘communion vessels, medical box, bed roll and scrambled ashore. But the landing ramp was damaged and two of the half-tracks could not make the sea at that depth. Meanwhile the water was rising and in the end the only thing to do was to wait for the tide to reach its height and recede again. This meant a frustrating wait of some six hours, with all hope lost of an early start.’15 Before the day was out his unit would lose two half-tracks, three armoured and three scout cars, some to friendly fire – from an American P-47 which mistook their vehicles out ahead for a German reconnaissance – but the padre would win a Military Cross by the war’s end. They were followed by Brigadier Foster, who had watched the initial assault from the frigate HMS Lawford, and with his main headquarters party was taken ashore in motor launches – wading through the surf at 0930, establishing themselves, as planned, at 1215 hours in Graye.

Further east, the Regina Rifles landed at Nan Green on the left bank of the Seulles. Known as the ‘Johns’ because of the number of ‘Farmer Johns’ in their ranks, they were delayed by the weather, with ‘A’ Company disembarking from the SS Isle of Thanet and ashore only at 0805 hours, the others later still. LCTs brought the armour of Major Frank Simpson’s 80th Assault Squadron, Royal Engineers, to the beach at the same time. Major Gordon Baird recorded that ‘Courseulles had been divided into twelve blocks, each was to be cleared by a designated company. Careful study of enlarged air photos made the ground itself easily recognisable. Every foot of the town was known before we entered.’16

Sergeant Léo Gariépy, commanding one of the DD tanks, remembered ‘Standing on the command deck at the back of my turret, trying to steer and navigate, was the longest journey of my life. I noticed that many of the tanks had sunk and the crews were desperately trying to board bright-yellow salvage dinghies. The struts which kept the rubberized skirt around the tank were groaning and I had visions of them giving out at any moment. On the beach, I gave orders to deflate the canvas skirt and what happened next will always remain vivid in my memory. The German machine-gunners were absolutely stupefied to see a tank emerging from the sea. Some of them ran away, some just stood up and stared, unable to believe their eyes. We mowed them down. The element of surprise was a total success’.17

This was probably the first beach where the Sherman swimming tanks delivered as they had been designed to: the Reginas arrived to discover fourteen out of nineteen ‘B’ Squadron DD tanks of the 1st Hussars had managed to swim ashore and were setting about the gun emplacements. Both found that they were overwhelmed quicker by tank–infantry teams. The bunkers containing the 88mm, 75mm and 50mm guns fell in succession to direct hits, though not before one of the German 75s had expended two hundred rounds at them, judging by the number of shell cases counted later. In return, one Sherman loosed off twenty-five rounds from its main gun before being stranded by the incoming tide. With the most dangerous weapons out of action, ‘A’ Company followed by the rest of the battalion pushed into the town, mopping up the east bank of the Seulles as they went.

In one of the bunkers opposing the Reginas, Heinrich Siebel assumed he was safe in his thick concrete emplacement housing the 88mm cannon. ‘We shot and shot, especially at the strange tanks that came up the beach’, he recollected. ‘It was hard for us to see much because of the smoke, but I believe we destroyed two before our gun received a direct hit. There was a flash and a great bang and I was blown backwards onto the concrete floor and knew nothing else for a time. When I woke up I found two of our men dead and I tried to get out through the rear exit, pulling one of my wounded friends with me, but debris made this difficult.’18

When swimming ashore, the mount of ‘B’ Squadron’s commander, Major Stuart ‘Stu’ Duncan, was flooded by an immense wave, which collapsed its protective canvas siding, forcing the crew to bail out two hundred yards short of safety. Trooper Larry G. Allen watched it happen. He recalled initially of his own tank, ‘shells began to fall around us, sending up miniature geysers of water. After what seemed to be hours I felt our tracks touch land.’ Then he looked to port and saw ‘the Commanding Officer was swimming merrily along on our left flank when his tank was seen to stagger, as a giant wave broke over the top. This acted like a hole in the dyke, the force of the water coming over the top caused the canvas to be forced down and in a very short time the tank was lost. The crew were seen throwing anything that would float overboard.’ Although Duncan and three of his crew swam to shore, Trooper Roswell Toffelmire drowned.19 In 1971 their tank, named Bold, was recovered from the sea and set up by the harbour as a memorial.

The Reginas were almost the only unit on D-Day whose task immediately on landing was to clear a built-up area. Lieutenant Bill D. Grayson of the Reginas’ ‘A’ Company dashed towards one of the defended buildings as a German threw a stick grenade at him. Grayson picked it up and threw it back, then – armed only with a Colt automatic pistol – followed a communications trench to an underground shelter, where he took thirty-five prisoners. He subsequently repeated this action several times in clearing Courseulles; perhaps unsurprisingly, a Military Cross later went to Grayson for his coolness under fire.20

The rest of the battalion left the comfort of the landing ships Llangibby Castle and Mecklenburg for the perilous journey ashore in which ‘D’ Company lost two LCAs to obstacles and mines hidden by the surf. This caused heavy casualties, including their commander, Major Jack Love – only two of the thirty-six men in his LCA reached the beach. ‘B’ and ‘C’ Companies recorded house-to-house combat as they cleared the town, but found Germans were returning by tunnels and trenches to reoccupy their positions, necessitating going over the same ground again. The narrow streets of Courseulles were especially challenging for the Shermans and Centaurs, and several tank commanders, heads out of their protective hatches, succumbed to snipers.

On the southern edge of town, when Sergeant Léo Gariépy saw a marksman fire at another tank, his vehicle charged up to the building and blasted the second-floor window on the right. He held his fire as a civilian woman emerged, a baby in her arms, then dismounted and leapt up the indoor stairs. Inside, Gariépy confronted a Frenchwoman, clutching a rifle, whose German boyfriend had been killed earlier. Mindful of the deaths of other tank commanders, he cut her down in an angry blast from his Sten gun.21 Meanwhile, the Reginas’ ‘D’ Company simply reorganised under the command of its remaining officer, Lieutenant Hector L. Jones, cleared a part of Courseulles, and set out as scheduled to Reviers, two miles away, where they arrived at 1100 hours. Battalion headquarters followed at 1500, and two hours later the unit moved south, taking Fontaine-Henry and Le Fresne-Camilly by eight that evening, where they dug in for the night. Both commanders of the two Royal Engineers assault squadrons would win a DSO that morning through dismounting from the safety of their tanks and directing the subjugation of individual houses, strongpoints and bunkers, ungumming the congestion that reigned on each beach, and dealing with the rising tide – all on top of a plan that hourly threatened to unravel with the much delayed timetable.

By the evening, ‘B’ Squadron of the 1st Hussars had reached Pierrepont, a mile south-east of Creully. Much earlier, however, they had lost five tanks to a single 88mm gun – possibly belonging to the 21st Panzer Division, which had deployed some of its anti-tank battalion to the area. As Sergeant Gariépy recalled, ‘I saw Lieutenant McLeod’s tank burst high in flame. The troop corporal’s tank suffered the same fate, and several others.’ Spotting the barrel of the perpetrator, Gariépy gave evasive orders to his driver, while telling his gunner to engage. ‘He fired two rounds, the second scoring a direct hit. I moved up to the gun emplacement and shot all the crew of fourteen cowering in the trench.’22 By then, ‘B’ Squadron was down to four tanks, out of nineteen.

Also in Pierrepont that first evening were the Canadian Scottish, hourly expecting a counter-attack which never materialised; they had suffered eighty-seven casualties, but had taken about two hundred prisoners. Laagering nearby, the 1st Hussars later noted, ‘In view of the losses in DD tanks due to the unsuitable weather, we ended D-Day with a considerably smaller number of tanks than was desirable for our first night in Europe, but by nightfall Harry Foster’s 7th Brigade was firmly astride the line running through Fontaine-Henri, Pierrepont and St Gabriel.’23 Foster later noted, ‘The outstanding features of the day were the admirable spirit of the men, and the excellent fire support of the artillery. No request for support went unanswered and many infantry professed to understand for the first time that the gunner’s role was something more than to block traffic.’24

Brigadier Blackader’s 8th Brigade Group assault in the east was of necessity far more spread out. The Toronto-based Queen’s Own Rifles of Canada would launch themselves at Bernières, while on their left, the North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment were to simultaneously tackle Saint-Aubin, each supported by a squadron from the 10th Armoured Regiment – better known as the Fort Garry Horse tank regiment, which recruited in Winnipeg, Manitoba. Reverend Raymond Hickey, chaplain to the North Shores, remembered of their cross-Channel journey, ‘Into the night we sailed as silently as thieves bent on their journey under the cover of darkness. Not a light showed in all that vast expanse of boats, but here and there, by the reflection of the water, you could make out the indistinct form of a boat, like a giant whale sleeping. Only the dull throbbing of the engines broke the silence.’

Hickey, aboard HMS Brigadier, a 2,000-ton former Channel ferry carrying six LCAs and 180 men from the North Shores, then vividly described the next morning, a common experience for all of the 3rd Canadian Division:

The engines had stopped and the boat was still. We rushed up to the deck and there about ten miles away was the coast of France, about to awaken to a tragic day. Overhead our planes droned past and in a few minutes the coast lit up with the well-known flares of bombing. Then, with a terrific crash, heavy guns on the destroyers behind us opened up and the air was filled with the whistling of shells speeding on their way to destruction and death. Breathless we stood and watched – and there before us broke the scarlet dawn! No sun came up; the clouds hung low and dark; the waves rose cold and unfriendly-like, and along the coast our bursting bombs and shells threw up a crimson curtain.25

The Queen’s Own Rifles were to put ‘A’ Company down west of Bernières and ‘B’ Company to the east, hoping to avoid the worst of the defences and envelop the town. After reveille at 0315 hours, Company Sergeant Major Charlie Martin of ‘A’ Company caught the moment of leaving the safety of their mother ship, HMS Monowai, the converted New Zealand liner: ‘All that remained within sight was our own fleet of ten assault craft, moving abreast in the early-morning silence in a gradually extending line facing the shore, ‘A’ Company boats on the right and ‘B’ on the left.’ However, instead of depositing the two assault companies either side of Bernières, the wind pushed them in front of the coastal settlement, looking into the muzzles of its defenders.

Waiting for them in WN28 was Grenadier Christian Hubbe, who had slept as usual in his bunker, but was woken before the naval bombardment started ‘by our Sergeant-Major who yelled that an enemy fleet was off shore and we must get to our battle stations at once. I will never forget the first sight of that invasion fleet. We were amazed and frightened and wondered how we could possibly repel such an armada. Then our Leutnant came to remind us of our drills and not to fire until the enemy was in the water and at their most vulnerable. At last the noise seemed to lessen and our Sergeant told us to Stand-to as the enemy were about to land, so we jumped to our weapons, trembling with fear. Then we could see the enemy landing craft coming in and the warships still firing. We forced ourselves to get ready’26

‘A’ Company immediately encountered heavy machine-gun and mortar fire, but managed to scramble off the beach and began clearing Bernières. ‘B’ Company were less fortunate, landing directly in front of a blockhouse which cut down sixty-five Riflemen within minutes. CSM Martin remembered:

the moment the ramp came down, heavy machine-gun fire broke out from somewhere back of the seawall. Mortars were dropping all over the beach. The men rose, starboard line turning right, port turning left. I said to Jack, across from me, and to everyone: Move! Fast! ‘Don’t stop for anything. Go! Go! Go!’ We raced down the ramp. None of us really grasped at that point – spread across such a large beach front – just how thin on the ground we were. Each of the ten boatloads had become an independent fighting unit. Bert Shepard, Bill Bettridge and I were running at top speed and firing from the hip.27

Being on the extreme right flank of the 8th Brigade attack, Martin’s company was also within range of the eastwards-facing 88mm at Courseulles, which set about his men with lethal shrapnel bursts. Lieutenant P. C. Rea’s platoon was almost wiped out: the officer was wounded twice, Lance Sergeant J. M. Simpson killed, and two-thirds of the men killed or wounded. Sergeant C. W. Smith counted their survivors – ten out of nearly fifty – and led them off the beach towards the railway station.28 CSM Martin and his mates, meanwhile, had spotted a small gap in the sea wall, defended by a lone machine-gunner. ‘We knew from our training that you cannot be on the move and fire accurately at the same time. If you stop you become a target. Bill Bettridge did stop for a split second. He took his aim and that seemed to be the bullet that took the gunner out, although Bert Shepard and I were firing too. We got to the wall and over it, then raced across the railway line.’29

‘We saw the five pillboxes on top of the seawall,’ recalled Rifleman Doug Hester, with ‘B’ Company. ‘These were our first objective. About five hundred yards out, they had us in their sights and began shooting. The Royal Marines lowered the door. The three in front of me were hit and killed. By luck I jumped out between bursts into their rising blood. Cold and soaking wet, I caught up to Gibby. The first burst went through his back pack. He turned his head grinning at me and said, “That was close, Dougie.” The next burst killed him.’30 Scrambling over the wall, Hester lobbed a grenade into a pillbox, prompting its three occupants to rush out, weapons in hand. One took aim with his Luger pistol but, as Hester later observed, ‘the Luger was no match for a Lee Enfield’.

Hester took some of the soldier’s possessions as keepsakes, including an inscribed prayer book. Later he mused, ‘We were the ones who carried bibles and prayer books. We were the good guys. Weren’t we? They were the bad guys. What’s he doing with a prayer book?’ In 1950, Hester returned the volume to the German’s family and was astonished to receive a reply from his mother: ‘We lost five children. Ernst was our last, the war took all that we possessed including five children. In this letter you find a photo of my son. Take this as a souvenir of a German comrade, whom you saw only dead, but who was, in the depth of his heart, never your foe.’31

Amidst the death and destruction there were some surreal moments. Rifleman Les Wagar with ‘C’ Company of the Queen’s Own Rifles watched a flight of Spitfires patrolling low overhead just as the drenching fire from the rocket ships erupted. The last aircraft collided with a rocket, exploded and fell into the water just offshore. The CO, Major Nickson, was trying to pick things out with his binoculars when he suddenly blurted out, ‘My God! There’s a Frenchman in a boat out there pulling the pilot out of the water.’32 Very many recollected the Spitfire’s demise, including Lieutenant Peter Rea, who pointed out, ‘I had the advantage of standing up, unlike my men who had to stay under cover and were very sick.’33 Major C. R. Wampach, Royal Engineers, recalled some Canadian sappers attacking a German blockhouse, when a hundred yards away they spotted a group of civilians standing together in a huddle. Their work completed with the pillbox and its occupants, the sappers advanced cautiously to the group. Though the soldiers were greeted with joy and delight when the locals found they could speak French, to the question ‘what the hell they were doing there?’, the Canadians could only shake their heads in wonder at the answer from the French group – they were waiting for a bus.34

The hardiness – or foolhardiness – of the Norman citizenry was further demonstrated in the war diary of the Queen’s Own Rifles, which observed ‘0940 hours. Battalion HQ arrives. At this time it is noted that a café just one hundred yards off the beach is opened up and selling wine to all and sundry.’35 John Powell, son of a village blacksmith, enlisted in the regular army in 1939. After surviving Dunkirk as part of Montgomery’s 3rd Division, he was posted to the 5th Royal Berkshires in 1942 when they became No. 8 Beach Group. ‘The training was nothing but a long, hard, boring slog; it was excitement about the second front that kept me going; I thought it would be sweet revenge for what I’d seen in 1940, but I was too busy at Bernières on D-Day to think about it much. My war was a mixture of extremely long periods of mind-numbing boredom mixed with very brief moments of being scared sh*tless.’36

On the Bernières beachfront, Lieutenant Herbert, Lance Corporal Tessier and Riflemen Chicoski rushed the main bunker, firing through the embrasures, then posted grenades through the gun slits and silenced it. The rest broke through the beach defences and moved into the town. By 0845 hours, ‘A’ Company had secured the road through the village to its south-western point, ‘B’ Company following suit, and by nine Bernières had fallen. Their supporting armour was delayed, not unreasonably because of the last-minute decision to take ‘B’ and ‘C’ Squadrons of the Fort Garry Horse DD tanks to within a thousand or so yards of the beach – mirroring what had happened at Gold. Blasting away at the bunkers from the shoreline, with an anxious eye on the rising tide, Major J. A. Meindl’s ‘B’ Squadron remained on the beach until 0930 hours, when the assault engineers cleared a gap in the sea wall, allowing the Shermans through.

Lieutenant Ian. C. Hammerton commanded the Sherman flail troop that landed with them. ‘Driver advance!’ he ordered: ‘As we pass down the LCT ramp my tank’s rotor jib strikes a tetrahedron, exploding a shell attached to it. But now we are moving onto a wide sandy beach and I can see the second flail already beating up to the wall. The AVRE tries petarding the sea wall for some time without success.’ Hammerton’s tank climbed a narrow concrete slipway leading to a gap in the sea wall and destroyed the Belgian gate obstruction at the top, but when he backed off to let an AVRE tow away the wreckage, ‘it tips over on its side, one track off the ramp. Another AVRE goes up the narrow ramp, pushes the wreckage and sets off a mine, which halts it on top of the wall.’ Hammerton towed away the damaged tank, which allowed a flail to exit ahead of him. Just as he was carefully lining up his Sherman to ascend the slipway, ‘Collinge, my driver says “Sir, the water’s coming in up to my knees.” Then the engine dies and we are flooded. “Bail out!” I yell.’37

It was a battle many vehicles lost on the narrow D-Day beaches, where the incoming tide drowned hundreds of valuable vehicles, including Hammerton’s mine-clearing tank. Later on in the day he would catch up with his remaining flails, and command the troop again, but his tank on the beach was a write-off. ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies of the Queen’s Own Rifles followed their colleagues, but suffered casualties in a different way, striking mined obstacles on the run in. However, Bernières and the inland villages of Anguerny and Anisy – seven miles inland, their D-Day objectives and where they dug in later on – came at a cost of 143 killed, wounded or captured.38 While ‘B’ Squadron’s leader, Major Meindl, was badly wounded, the rest of his tanks patrolled in a circuit between Fontaine-Henry and Anguerny. It was at about 1500 hours from high ground near Thaon that in the mid-afternoon haze they spotted the 3rd Canadian Division’s ultimate objective – Carpiquet airfield, six miles distant. Tantalisingly close, it would not fall into their hands for another thirty-three days.39

While the Queen’s Own Rifles were busy with their war in Bernières, Lieutenant Colonel Don Buell’s North Shore (New Brunswick) Regiment were assaulting Nan Red at Saint-Aubin, landing in LCAs from HMS Brigadier and SS Clan Lamont at 0810 hours. They had been preceded by a rather eccentric naval bombardment, which Lieutenant J. G. Pelly aboard the destroyer HMS Eglington wrote about to his parents soon afterwards:

we were so close one could plainly see people opening windows or cycling, and it was with sadistic delight that we knocked things down. Finding hardly any opposition, and thus probably few gunsights, the Captain chose his own targets and we were so close that we couldn’t miss. Down came a tower, the top of the gasworks went for six; any German who ran out of a house up the street had four-inch shells overtaking him. In fact we had the time of our lives – all pointing out targets and shooting up anything that took or didn’t take our fancy – like the green house the Captain thought to be an eyesore.40

The Eglington should have been engaging the shoreline bunkers, but was probably aware that her puny four-inch shells would not destroy them. All they could hope to achieve was to distract or harass the defenders while the infantry fought it out with them. Reverend Hickey with the North Shores noted that

the sea was rough. Soon the area was dotted with our little boats bobbing up and down like sea gulls on a choppy sea. We lined up in position and started slowly over the ten miles to shore. The last three miles were to be covered with a burst of speed. Joel Murray from Cross Point and I landed together in the water but we could reach bottom and made shore. A young lad next to me fell, a bullet got him. I dragged him ashore, and there in that awful turmoil I knelt for a second that seemed an eternity and anointed him – the first of the long, long list I anointed in action.41

‘Tracer bullets seemed to fill the air as we came in’, recollected Lieutenant Richardson of No. 4 Platoon. ‘In our boat morale was never higher and the platoon was merrily singing “Roll Me Over, Lay Me Down” as we approached the shore. The Germans held fire until we were fairly close in. Our first casualty was when an armour-piercing bullet came through the LCA and struck Private White a stunning blow on the forehead.’42 Lieutenant John ‘Bones’ McCann recalled, ‘We found the guns and emplacement, which were to have been put out of business by the air force, intact and very much in use. Also, Jerry had a beautiful underground system of communicating with his pillboxes. Things weren’t going as planned, and unless we captured those heavy guns Jerry was potting landing craft with, things were going to get worse.’43

McCann was describing the 50mm gun still in place on the Saint-Aubin seafront today, which is where ‘B’ Company landed. To attack it the North Shores had a mad dash of three hundred feet to reach the cover of the high beach wall, where many of the battalion sheltered – a gap that constantly narrowed as the tide came in. Hickey, the North Shores’ chaplain, remembered the wide, open beach between the water’s edge and the cement wall: ‘If you could make the wall you were safe, for a time at least, from the enemy fire; but ah, so many of our fine young men didn’t make it. The beach was sprayed from all angles by the enemy machine-guns and now their mortars and heavy guns began hitting us.’44

All the New Brunswickers remember the open beach littered with the dead or dying. Hickey’s job was to retrieve them,

so with our stretcher bearers and first aid men, Doc Patterson and I crawled back again across that fifty yards of hell. By the little disc around their neck I knew their religion. If Catholic, I gave them Extreme Unction with one unction on the forehead, but whether Catholic or Protestant, I would tell the man he was dying and be sorry for his sins, and often I was rewarded by the dying man opening his eyes and nodding to me knowingly. It was a hard job to get the wounded on the stretchers and carry them to the shelter of the wall. I will never forget the courage of the stretcher bearers and first aid men that morning.

East-facing intelligence postcard of Nan Red beach at Saint-Aubin (top), with its high sea wall, assaulted by the Reverend Raymond Hickey and the North Shore Regiment. They were told to orientate themselves using the distinctive ‘witch’s hat’ roofline (see arrow). The pointed roof is visible in the below image, having survived the naval bombardment. An endless tangle of barbed wire hangs down from the sea wall. Below it a DD tank of ‘C’ Squadron, the Fort Garry Horse, lies where it was knocked out. The P-47 plane belonged to 2nd Lieutenant John A. Weese of the 386th Fighter Squadron, shot down on 10 June. It crashed into the sea; the pilot died and his aircraft was dragged ashore. (NARA)

At one stage Hickey went over the sea wall to rescue more wounded and mused how on earth he survived. ‘I like to think that a German sniper had me in his telescopic sight, but when he saw by my collar and red cross arm band that I was a chaplain, he stayed his finger – well, I like to think it.’45

Three swimming Shermans of the Fort Garry Horse had to be abandoned when their LCT sank beneath them, trapping them in the wreck, and a fourth disappeared beneath the waves. The remaining fifteen of ‘C’ Squadron started waddling to the beach following the infantry of the North Shores, putting effective fire onto the defenders. However, the armour could find no quick exit from the beach and waited for the Royal Engineers’ AVREs to provide some – the latter, however, were late. Therefore the squadron’s commander, Major William Bray, pointed his own tank at the minefield and ordered the squadron to follow him. They lost three more Shermans to mines, but forged into the town. Soon Saint-Aubin was under Canadian control except for the 50mm strongpoint, which only fell after four hours of bitter fighting. Its forty-eight surviving defenders were lucky the North Shores accepted their dirty-white rags of surrender.

On the western edge of town, ‘A’ Company managed to break through and after two hours of combat and twenty-five casualties, had linked up with the Queen’s Own Rifles on their right, allowing the war diary to boast, ‘At 1115 hours, four hours and five minutes after landing, the area was cleared. Thus one of the Atlantic Wall’s bastions which had taken four years to build, was completely reduced. Forty-eight prisoners of war were taken and it is estimated the same number were killed.’46

As soon as he landed with the British 62nd Anti-Tank Regiment, driving an M10 Tank Destroyer, Gunner Roland Johnston was presented with the ugly side of war. Attached to the North Shores, he never forgot that, ‘When we got to the beach we drove straight off and had to run right over a lot of casualties to get up the beach. You had to put it out of your mind. Just forget about it. There was only one way up and a lot of the infantry were still in the water. They were pinned down and took cover behind every tank that went up the beach.’47

Of 48 Commando landing with the Canucks on the eastern flank, Royal Marine Dennis Smith recollected that their plan ‘was to land on the beach just to the right of the church spire in Saint-Aubin, towards Bernières’.48 This was to have been after the 8th Canadian Brigade, whose task was to secure the beach, using the North Shore riflemen assisted by the armour of the Fort Garry Horse. With the violent weather delaying both the infantry and the tanks, the current instead dumped much of 48 Commando in front of the unsubdued, strongest German positions. Nearly half their landing craft were disabled or destroyed by Rommel’s obstacles – implying that even more obstructions and better-trained defenders might well have defeated the landing.

Some of those who waded into the violent surf with their heavy packs perished. The unit’s war diary recorded that ‘A’, ‘B’, ‘X’ and HQ Troops

were able to wade ashore in about three feet of water, but ‘Y’ and ‘Z’ Troops could only get ashore by swimming. Many officers and men attempted to swim ashore from these craft and a high proportion of these were lost through drowning, owing to the strong current. Some got to land. The commander of ‘Y’ Troop, Major Derek de Stacpoole [son of an Anglo-Irish Duke] just made the beach although wounded before he left his LCI. His craft had been damaged by an obstacle and being unable to land, personnel were shuttled ashore by LCT. Captain Frederick Lennard, a strong swimmer was drowned. TSM [Troop Sergeant Major] Trewers was carried far to the east and landed under the guns of the strongpoint at Langrune.49

What the war diary tactfully overlooked was that disembarkation was painfully slow from de Stacpoole’s damaged LCI. With casualties mounting from incoming fire, the LCI commander lost his nerve and set sail for England with fifty commandos still on board. An incandescent Stacpoole argued vigorously. Muttering ‘That’s absurd’, along with fruitier epithets, the twenty-five-year-old already-wounded officer promptly dived overboard, rather than miss his appointment fighting the Germans. Twenty minutes later, hard on 48’s heels, two more LCIs brought Brigadier Leicester with his 4th Special Service Brigade headquarters to Saint-Aubin – welcome reinforcements, but adding to the cluttered beach. This was a graphic illustration of the chaotic experiences of the other Canadian assault battalions caught in near gale-force seas off Juno, as well as those on Gold and Omaha.

Due to the foresight of their CO, Lieutenant Colonel James Moulton, 48 Commando’s casualties were lower than they might have been.50 He had trained his men to fire two-inch mortar smoke from the bows of their LCAs during the approach to the beach. The smoke hid those exiting the damaged craft onto the beach. Commanding HQ Troop, Captain Daniel Flunder noted, ‘The surf was incredible, with beached and half-sunken landing craft wallowing about in it.’51 Depleted in numbers and soaking wet, they found the beach a chaotic and confusing environment, having to rush the sea wall with the New Brunswickers. The commandos thus landed in the middle of the battle for the shore.

Sergeant Clive ‘Joe’ Stringer from Brownhills in the English Midlands remembered his CO gathering all the survivors together – roughly fifty per cent of 48 Commando were missing at that stage – reallocating tasks and calling ‘Forty-eight, this way!’: ‘It was really chaotic and this is where Colonel Moulton really shone.’ Three troops were down to half strength, while ‘Y’ and ‘Z’ had only some forty-five (out of 130) between them, Headquarters had lost twenty men and Support Troop had a single three-inch mortar and one Bren gun. As Stringer listened to the commander of ‘B’ Troop issue his orders in one of the seafront houses, ‘Captain James Perry stepped outside to take a last look and was hit and killed by a sniper’s bullet.’52

On the beach Captain Daniel Flunder watched with slow-motion horror as one of the newly arrived Fort Garry’s Shermans, hatches down, trundled along the sand: ‘I was sickened to see it run over two of our wounded and was heading for our good padre [chaplain], John Armstrong, who had been badly wounded in the thigh.’ Flunder sprinted down the beach shouting, ‘They’re my men! They’re my men!’ He reached the tank and hammered on its turret with his stout ash walking stick, the surf having robbed him of all his other weapons and equipment. ‘When this failed, I stuck a Hawkins anti-tank grenade in the sprocket, pulled the pin and blew the track off – that stopped it.’53 Reverend Hickey, the North Shores’ chaplain, also recollected the moment: ‘The noise was deafening; you couldn’t even hear our huge tanks that had already landed and were crunching their way through the sand; some men, unable to hear them, were run over and crushed to death.’54

Once through the beachfront houses, the commandos dumped their heavy packs in the small orchard of a house and fought their way through Saint-Aubin, garden by garden. Overwhelming Saint-Aubin cost them three hours of fierce fighting – a job they had thought would be accomplished prior to their arrival. Marine Dennis Smith remembered ‘two young girls looking at him in bewilderment from the window of their house, before being pulled away by their mother’. They would attack the WN26 strongpoint at Langrune, which would not fall until the following morning, but on the way there Smith encountered his first French casualty, a youth lying dead in the road, next to his bicycle.55 The attrition of leaders was great: of the twenty-five officers of 48 Commando, photographed at their camp in Southampton before D-Day, nine would perish.

Reverend Hickey observed that ‘like a hospital patient you lost all idea of time in action. Time meant nothing. We were told after that we had been on the beach for two hours.’ Eventually he recalled leaving the beach and ‘following a little path that led through an apple orchard, we reached the one cobble stone street of Saint-Aubin’.

There Hickey met his first French casualties:

A man ran across the street, he wanted help; we followed him into his house and there on the floor lay his young wife badly wounded. Doc Patterson stopped the bleeding with a first aid dressing, and she tried to bless herself when I told her I was a priest and would give her Absolution and Extreme Unction. Their children, three little girls of about four, six and eight, looked on terrified, maybe as much because of us as their mother. I spoke to them, but it only seemed to terrify them all the more.

In a gesture replicating the interaction of Lance Corporal Albert Gregory with Arlette Gondrée at the Pegasus Bridge Café, Hickey then remembered he had ‘three chocolate bars in my pocket, part of my day’s rations. I gave them to the little girls. Oh the power of a chocolate bar! The terror vanished from six brown eyes, and even as terror reigned, the three little girls attempted a smile as I patted their curly heads.’56

Not all the civilians had been evacuated: Jeannine Mahia, then a young girl living in Langrune, was woken up by the shelling. As she told me in 2008, her family hurried down to their basement shelter, she noticed with astonishment that the sea was ‘so black with ships that it was as though a sprawling city had secretly arrived in the night and been built just off our beach. At first I did not trust my eyes. We could not see any ocean between the separate boats: it was a solid mass. Their masts stuck up like the trees and towers of a town. It was overwhelming for us. Only the day before we had looked out and noticed the Germans kicking a ball about on the sand, like children, and then the water was empty. How all those vessels suddenly got there without anyone knowing was a complete mystery to us.’57

By 0945 hours, the entire North Shore Regiment was ashore, had met up with the Fort Garry’s Shermans and were advancing towards Tailleville. The latter noticed maybe one hundred Germans withdrawing from Saint-Aubin towards the village, whose château here housed not only the local Gestapo detachment, but the military headquarters of two neighbouring units – Hauptmann Deptolla’s Second Battalion and Hauptmann Johann Grzeski’s 8th Company, both of the 736th Grenadier-Regiment. ‘It was a real bird shoot. We caught them in the open, with all the guns. The exhilaration after all the years of training, the tremendous feeling of lift. It was like the first time you had gone deer hunting’, noted one of the Fort Garry Horse.58 However, Tailleville château would prove an altogether more difficult fight. With several underground bunkers, a communications centre and tunnels connecting Tobruks with machine-guns, mortars and a 50mm cannon, the Germans had designated this position, a mile from the sea, as WN23. It represented the beginnings of Rommel’s planned second defensive line, inland from the coastal strongpoints.

A strong stone wall ringed the perimeter into which many loopholes had been drilled (they are still there today), and at least one tree, used as an observation and sniper post, remained in 2014, bearing metal staples hammered into the trunk allowing access to the upper branches. ‘C’ Company’s Major Ralph H. Daughney’s report of this engagement read, ‘At 1015 hours we started our advance towards Tailleville with a troop of tanks. Progress was slow on the account of mortars and machine-gun fire, as well as sniping, coming from the direction of the Château. It was not until 1730 that this was finally taken and 1900 hours before the entire complex had been searched and some seventy prisoners being taken.’59 The German defence was ferocious, their last message to General Richter in Caen was entered at 1548 hours: ‘Hand to hand fighting inside command post. Hemmed into a closely confined area, but still holding out. Heil Hitler.’

Reverend Hickey observed that

the place was an old château hidden in a clump of trees; it looked as silent as an abandoned farmhouse, but, when we got in range, every tree spoke with a tongue of fire. Quickly we dug in with the small shovels we carried on our backs. How you can dig when you’re digging for your life! Foot by foot our men advanced through the network of trenches and barbed wire around the chateau. The Germans took their last stand inside the building and fought on till our tanks came up and blasted the side out of the place. Finally, about twenty Germans, with their hands in the air, ran out to surrender. The rest of their garrison lay around the yard or in the chateau, dead. They were the first German prisoners I had seen. They stood trembling with their hands up, you could see they thought we were going to shoot them. And now, when I recollect, I almost think shooting would have been more merciful than the awful barrage of words and tongue lashing they got from Captain McElwain.60

The North Shores continued to search the bunkers and tunnels at Tailleville, and reported capturing more prisoners at 2300 hours, including ‘two wounded monocled officers’. In The Scarlet Dawn, Hickey’s 1949 account of his war, the chaplain recorded that Tailleville

was a maze of trenches and underground passages. One trench ran right to the beach. We knocked down the door of one underground passage and out trotted a dozen horses, three or four cows and a flock of hens, cackling their indignation. The Germans must have intended to make a stand there. What we were most afraid of now were booby traps. You might innocently open a door and step right into the next world; or press the starter of a newly acquired German car and go sailing through the air with it.61

The hard-won battle for Tailleville was unexpected and in some ways more difficult than the much anticipated and planned capture of Saint-Aubin, despite the loss of one officer, Major J. A. MacNaughton, thirteen men killed, and several wounded (one was Alphonse Noël, commemorated by a plaque in the village today). Before the end, the North Shores had brought up portable flame-throwers to winkle out the last of the die-hards. By ten that evening the North Shores had gone firm anchored around Tailleville but had suffered 125 casualties during the day.62

A mile away lay another of this inner belt of fortifications. The Luftwaffe radar station outside Douvres, labelled WN23a, originally had had little in the way of protection. Under Rommel’s initiative in 1944 the twenty-acre site had been upgraded to include thirty concrete structures, its main command bunker extending five storeys underground. Led by Oberleutnant Kurt Egle of No. 8 Company, 53rd Luftnachrichten (Luftwaffe Signals) Regiment, some 238 personnel, including electricians, engineers and thirty-six air controllers, were stationed here, with their own diesel generators powering several devices, multiple cannon, machine guns and minefields. Although it was bombarded by naval gunfire and its radars inoperative, the Canadians observed many troops entering its perimeter and decided to bypass it on 6 June. The decision was wise. The Douvres garrison would prove too strong to subdue until 41 Royal Marine Commando overwhelmed the site eleven days later, on 17 June, with tank and engineer support.63

The 8th Brigade reserve battalion, Lieutenant Colonel J. B. Mathieu’s Régiment de la Chaudière, was split between four transports, the Lady of Man, Monowai, Clan Lamont and, appropriately, a Canadian vessel, HMCS Prince David. They would not begin to arrive until after 0830 hours, following the Queen’s Own Rifles into Bernières. Landing on the rising tide, several of their LCAs struck mines and obstacles ensuring many Chauds had to swim ashore. The coxswain of one of these was Jim Baker, a Royal Marine from Blackpool, assigned to the Monowai’s 445th LCA Flotilla.

We were packed with thirty-eight lads of the Chauds, with two other RM crew members … We lost ten of our twelve LCAs to enemy gunfire and mines, which left just two of us in that final assault to the beach. When we got to within a thousand yards of the shore, I looked across at my pal, ‘Hooky’ Walker – coxswain of the other LCA – who gave me a thumbs-up and a broad grin to say ‘we’ve made it; we’re there’, but I froze. I could see three Teller mines strapped to an obstacle just under his bow. It vapourised him, the boat, the troops, everything – all gone in a split second. The blast blew our boat up in the air to about twenty feet and we came down amongst the beach defences of Bernières. That was how we landed … Once up the beach, we came under more fire from the church; this time it was snipers. By this point we were climbing over bodies, already victims of sniper fire and mortars. Using these and whatever we could find for cover, we reached the church and the sergeant climbed the tower. In the mood everyone was in, there was no mercy shown to the sniper he found.

Wounded by a mortar bomb shortly afterwards, Baker would be awarded the Distinguished Service Medal for his exploits.64 Leaving the 7,000-ton Clan Lamont, Lance Corporal Reg Clarke’s LCA of the 558th Royal Marine Assault Flotilla found navigation difficult in the

black acrid smoke and sea spray. There was a terrific jarring, grating sound underneath, as though the whole bottom of the craft was being torn out. We all lurched forward with the impact. I gripped my rifle. The stench of spilled diesel oil and cordite stung my nose and made my eyes water. Two explosions occurred about fifty yards to our left. Water spurted up and showered down onto our craft in an absolute deluge. We surged back a bit from the beach then moved forward again, dug in and held, ‘bottomed’. Crash! Down went the armoured ramp and we had our first view of the beach.