Evliya Efendi begins his Seyahatname by giving what he calls ‘an account of the ancient city and seat of Empire of the Macedonian Greeks, the well-guarded Constantinople, the envy of all the kings of the Land of Islam’. Evliya’s version of the city’s foundation is, as we might expect, fabulous. He informs us that ‘all the ancient Greek historians are agreed that it was first built by Solomon, son of David, 1600 years before the birth of the Prophet. They say he caused a lofty palace to be erected by Genii, on the spot now called Saray Point, in order to please the daughter of Saidun, sovereign of Feridun, an island in the Western Ocean.’

At the time when Evliya was writing his description of the city, in the middle of the seventeenth century, memories of the Byzantine Empire had all but taken on the quality of legend. Aside from perhaps a score of churches, most of them by then converted into mosques, there remained in the city only some scattered ruins of imperial Byzantium. And so, in his customary way, Evliya invested these ruins with fabulous histories, claiming that many of them were magical talismans which had since antiquity protected the city of Constantinople. Many of Evliya’s supposed talismans are still standing today, although, from the condition of the modern town, they would seem to have lost their magical powers. But there are those of us for whom some magic still remains, for these talismanic ruins can evoke the fabled past of Byzantium, especially with Evliya Efendi at one’s side.

Pride of place among these ancient monuments should perhaps be given to the Column of Constantine, although Evliya ranks it only second among the talismans of the city. This column was dedicated by Constantine the Great on May 11 in the year AD330, the day on which Constantinople officially became the capital of the Roman Empire. The column, which was originally surmounted by a statue of the Emperor himself, stood in the centre of the Forum of Constantine, now a minor intersection on the Avenue of the Janissaries. The identity of the column and its historical significance were almost forgotten by Evliya’s time. Nevertheless, the name of Constantine the Great still seems to have been associated with it, as we can see from Evliya’s description: ‘In the Poultry Market there is a needle-like column formed of many pieces of red emery stone, a hundred royal cubits high. This was damaged by the earthquake which occurred on the two nights during which the Pride of the World (Mohammed) was called into existence; but the builders girt it round with iron hoops, as thick as a man’s thigh, so that it is still firm and standing. It was erected 140 years before the era of Iskender (Alexander the Great). Kostantin (Constantine the Great) placed a talisman on top of it in the form of a starling, which once a year clapped its wings and brought all the birds in the air to the place, each with three olives in its beak and talons.’

The second of the city’s surviving imperial columns, the Column of Marcian, stands in the centre of a quiet little crossroads near Beyazıt Square. This column, huge as it is, was completely lost sight of for centuries and almost forgotten, for it stood in the garden of a private house. But then, in the great fire of 1908, the surrounding houses were burned to the ground and the column was once again exposed to public view. (Do we detect here the crime of an antiquarian-arsonist?) On the pedestal of the column there are still visible the figures of two Nikes in high relief; one of them holds a basket decorated with a cross and myrtle leaves. Below these figures we can make out the outlines of an inscription in Latin. It reads: ‘Tatianus Decius raised this column for the Emperor Marcian. December 450–July 452.’ The Turks call this column Kız Taşi, or the Maiden’s Column, because of the reliefs of the two Winged Victories which appear on the pedestal. This has led them to confuse the Kız Taşi with the famous Column of Venus, which also stood in this neighbourhood; this column reputedly possessed the power of being able to distinguish true virgins from false ones. Evliya Efendi listed the Maiden’s Column as the third of the city’s talismans, giving this brief description: ‘At the head of the Saddler’s Bazaar, on the summit of a column stretching to the skies, there is a chest of white marble in which the unlucky daughter of King Puzantin lies buried; and to preserve her remains from ants and serpents was this column made a talisman.’ Talismanic protector of a dead princess and indicator of false virgins; this is indeed a fabulous column!

Of the other imperial columns which once studded the city only a solitary but fascinating fragment remains. This is the base of the Column of Arcadius, which stands in the lovely old district of Samatya. This column was erected by the Emperor Arcadius in 402 to commemorate his victories over the Goths and Visigoths. At the top of the column there was an enormous Corinthian capital surmounted by a colossal equestrian statue of Arcadius, placed there in 421 by his son, Theodosius the Lesser. This statue was eventually toppled from the column and destroyed in 704. The column itself remained standing for another thousand years, until it was deliberately demolished in 1715, when it was feared that it might fall on the neighbouring houses. All that remains today is the base of the monument, a battered mass of blackened stone completely overgrown with ivy and wedged in between a bakery and an old wooden tenement. Evliya, who saw the column before it was destroyed, numbered it first in his list of the city’s talismans. After describing the column itself, he gives this account of its talismanic powers: ‘On the summit of the column there was anciently a fair-cheeked figure of one of the beauties of the age, which once a year gave a sound, on which several hundred thousand kinds of birds, after flying round and round the image, fell down to earth and being caught by the people of Rum (Rome), provided them with an abundant meal. After, in the age of Kostantin, the monks placed bells upon it, in order to give alarm on the approach of an enemy. Subsequently, on the birth of the Prophet, there was a great earthquake by which the statue and all the bells on top of the figure were thrown topsy-turvy and the column itself broke into pieces; but being formed by the talismanic art it could not be destroyed and part of it remains as an extraordinary spectacle to this day.’

Evliya tells us that another half-dozen talismans are to be found in Altımermer, the district of the Six Marbles. The eponymous marbles, presumably columns, from which the district takes its name probably stood in or near the enormous Roman reservoir which is located in that area. This reservoir, anciently called the cistern of Mocius, was constructed towards the end of the fifth century, during the reign of Arcadius. Though the columns which Evliya describes are no longer to be found in the reservoir itself, there is a tradition which holds that they are the ones which now stand in the colonnade of the nearby mosque of Hekimoğlu Ali Paşa. Evliya outdoes himself in describing these talismanic columns, telling us that ‘every one of them was an observatory, made by some of the ancient sages’. The sages with whom Evliya associates these talismans are a most formidable group, namely: Hippocrates, Socrates, Pythagoras, Plato, Aristotle, Galen and King Philip of Macedonia, who would surely be surprised to find himself in the company of such distinguished intellectuals. On one of the columns stood a brass fly which, by its incessant humming, drove away all flies from the city, and on the second stood the figure of a gnat, which performed a similar service. On a third column stood the figure of a wolf which protected the flocks of the city from the attacks of real wolves. On a fourth column there was the figure of a stork which once a year let out a cry, whereupon all the storks within the city fell dead. Evliya tells us that this is the reason why storks do not build their nests within the city walls but prefer the suburb of Eyüp, on the upper reaches of the Golden Horn. These last two talismans would appear to be effective even now in protecting the town, for wolves are never seen in the streets of Stamboul and storks still nest only in Eyüp. But in warm weather the town swarms with flying insects, and so the brass fly and gnat must have disappeared or lost their powers. As Evliya tells us: ‘Wonderful talismans were destroyed, they say, in the time of that asylum of apostleship (Mohammed) and are now buried in the earth.’

The fifth and sixth talismans in Altımermer performed services of a different kind, according to Evliya: ‘On one of these columns were the figures of a youth and his mistress in close embrace. Whenever there was any coolness or quarrelling between man and wife, they were sure that very night to have their afflicted hearts restored by love if either of them went and embraced this column, which was moved by the spirit of Aristotle … Two figures in tin were placed on another column; one was a decrepit old man, bent double; and opposite to it was a camel-lip, sour-faced hag, no straighter than her companion. When a man and wife did not lead a happy life together a separation was sure to take place if either embraced this column, which was placed there by the sage Galen.’

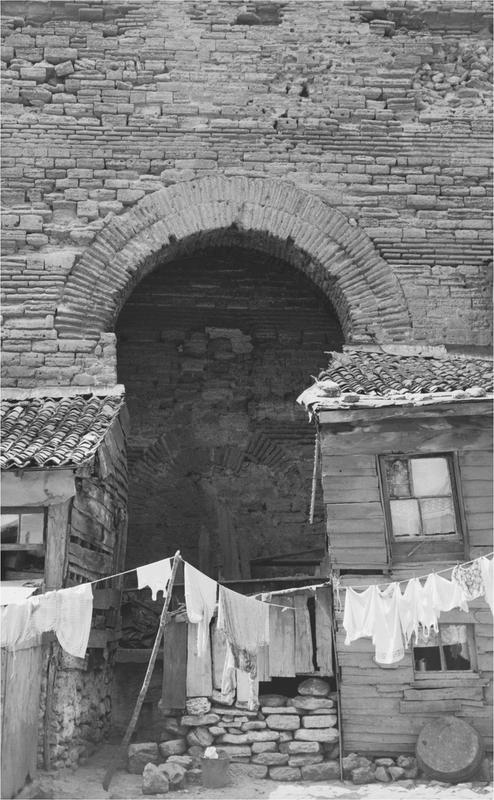

Gypsy houses leaning against Byzantine walls

Although Evliya originally told us that there were six talismans at Altımermer, we find in reading his account that there were actually seven. This extra talisman was a brazen cock placed there by Socrates. As Evliya informs us: ‘This cock clapped its wings and crowed once in every twenty-four hours, and on hearing it all the cocks in Istanbul started to crow. And it is a fact that all the cocks there crow earlier than those of other places, setting up their ku-kirri-ku at midnight, and thus warning the sleepy and the forgetful of the approach of dawn and the hour of prayer.’ We are told by a sleepy and forgetful friend in this neighbourhood that the brazen cock of Socrates must still be active, for he is awakened long before dawn each day by cocks crowing in the cistern of Altımermer. The cistern, which has been dry for centuries, now serves as a fruit orchard and vegetable garden. A picturesque farm village has grown up within the cistern, a curiously rural community isolated in its vernal, subterranean world, providing a pleasant contrast with the densely populated urban slum around it. The tops of the smoking chimneys, the minaret of the village mosque, and the upper branches of the flowering fruit trees reach up barely to the level of the surrounding streets. Evliya Efendi tells us that we can descend into this little arcadia down a stone staircase called the Forty Steps, although, as he hastens to add, the actual number of steps is fifty-four. The Turks call this lovely place Çukurbostan, or the Sunken Garden.

Three of the most fascinating of Evliya’s talismans stand on the site of the ancient Hippodrome, reminding us of the illustrious past of that famous arena. The site of the Hippodrome is today a quiet, tree-shaded park before the mosque of Sultan Ahmet. The street which borders this park follows exactly the course of the ancient racetrack. The Kathisma, or royal enclosure, was located at the northern end of the arena, where now reeks a public toilet. Of the many monuments and works of art which once adorned the Hippodrome only three remain, standing in line along what was once the spina, the longitudinal axis of the arena. They have survived, as Evliya would say, because they were fashioned by the talismanic art.

The first of these monuments, beginning at the southern end of the arena, is a huge obelisk of squared stones called the Colossus. Evliya numbered this obelisk as the fifteenth of the city’s talismans, describing it in his inimitable style: ‘It was constructed by Kostantin’s order of various coloured stones, collected from the 300,000 cities of which he was king, and designed to be an eternal monument to his power, and at the same time a talisman. Through the middle of it there ran a thick iron axis, round which the various coloured stones were placed, and they were all kept together by a magnet as large as the cupola of a public bath, which was fixed on its summit.’

The second in line of the ancient monuments in the Hippodrome is the Serpentine Column. This strange column has had a most interesting past. The three intertwined bronze serpents which form the column once served as the base of a golden trophy which stood in the Temple of Apollo at Delphi. This trophy was originally presented to the temple by the thirty-one Greek cities which together defeated the Persians at the battle of Plataea in 479BC. The column was brought from Delphi by Constantine the Great and eventually erected in the Hippodrome. The three serpent heads were broken off and lost sometime after the Turkish Conquest in 1453. Evliya Efendi has something to tell us about this in his description of the Serpentine Column, which he numbers seventeenth among the city’s talismans: ‘A sage named Surendeh, who flourished in the days of error under King Puzantin, set up a brazen image of a triple-headed dragon in order to destroy all serpents, lizards, scorpions and suchlike poisonous reptiles. It remained uninjured till Sultan Selim II, surnamed the Drunkard, knocked off with his mace the lower part of that head of the dragon which looks to the west. Serpents then made their appearance on the western side of the city, and since that time have become very common in every part of it. If, moreover, the remaining heads should be destroyed, Istanbul will be completely eaten up by vermin.’

The two remaining heads were lost after Evliya’s time and his dire prediction came to be fulfilled, for Stamboul today is literally overrun by vermin. But one of the missing serpent heads has been rediscovered and is now exhibited in the Archaeological Museum. In view of Evliya’s warning, it is imperative that this talismanic fragment be restored to its proper place without delay.

The third of the Hippodrome’s surviving monuments is the Egyptian Obelisk, which stands in the centre of the spina. It was originally commissioned by the Pharaoh Thutmose III, who erected it at Deir el Bahri in upper Egypt around 1550BC. The obelisk was brought to Constantinople and erected in its present location by Theodosius the Great in the year 390. Evliya lists the Egyptian Obelisk as sixteenth among the talismans of the city. He tells us that ‘this is an obelisk of red coloured stone, covered with various sculptures which foretell the fortune of the city. It was erected in the time of Yanko ibn Madiyan, who is represented on it sitting on his throne.’

The sculptures of which Evliya speaks are carved in low relief on the four sides of the pedestal which supports the obelisk. They are of particular interest because they show us something of what the Hippodrome was like fifteen centuries ago. One panel shows the Emperor Theodosius supervising the erection of the obelisk. Another shows the Emperor and his family looking down into the arena where a group of captives offers tribute to them. In a third panel of the obelisk the royal family is shown seated in the Kathisma watching a chariot race, and in the last panel Theodosius holds a laurel wreath and prepares to crown the winner. Below the Kathisma we see the faces of the crowd in the stadium; their features, like those of the royal family, are worn and broken by the centuries. At the bottom of this panel we can make out the figures of a line of female dancers performing in the arena. Behind the dancers three musicians are playing in accompaniment; one seems to be working a laterna, another is playing on a stringed instrument, and the third is blowing on a double Lydian flute. The dancers have their arms linked together and their leader has her free hand raised in the air. Looking at their graceful postures we seem to recognise the movements of the kesapico, one of the oldest of all Greek folk-dances. During the days of Byzantium the kesapico was performed annually in the Hippodrome on Easter Monday, and it is still danced today in the few Greek tavernas which remain in Istanbul. Looking at the worn frieze of dancers on the pedestal, we are reminded of the antiquity of all practices in this talisman-protected town.

The Hall of the Black Eunuchs in the Harem