It is not until the second half of Book II of the Seyahatname that Evliya finally begins his account ‘of all the Guilds and Professions, Merchants and Artisans, Shops and Various Occupations in this vast town of Constantinople, with the Regulations handed down to them by their Sheikhs or Ancients’. Evliya’s account is based upon his observation of the extraordinary public muster which was ordered in 1638 by Sultan Murat IV, in preparation for his march upon Baghdad. As Evliya writes, quoting the Sultan: ‘“Dear companions, and you Mufti Yahya Efendi, if it please God we will wrest Baghdad from the hands of the Persians, and deliver from their heresy the tomb of the founder of our orthodox sect. In order to assist me in our great expedition, I desire that all the guilds of Constantinople, both large and small, shall repair to my imperial camp. They shall exhibit the number of their men, shops and professions, according to their old constitutions. They shall pass before the Alay Köşkü with their Sheikhs and Chiefs, on foot and on horseback, playing their eightfold music, so that I may see how many thousand men and how many guilds there are. It shall be a procession the likes of which was never seen before.”’

It was indeed, according to Evliya’s description of the parade, one of the last of its kind ever to be seen in Stamboul. During Ottoman times these imperial processions were held but once or twice a century. They served as a kind of perambulatory census of the trade and commerce of the city, often as part of the preparations for a great military campaign such as that of Murat IV. The Sultan viewed his passing citizens from the Alay Köşkü, the Kiosk of the Processions, a huge gazebo projecting from the outer defence-wall of Topkapı Sarayı just opposite the Sublime Porte. Seeing the kiosk today, we are reminded of the lively and colourful procession which passed before it in Evliya’s day.

As Evliya describes it, the procession was led by the Çavuş, or Ushers, ‘upon whom it is incumbent to collect and assemble the rest. Their patron is Malek Ushtur, who from having killed a dragon in China is vulgarly called Ejder (Dragon), but who got his name from having lost one of his eyes in battle. The Çavuş adorn their horses in honour of their patron with sea-horse bristles and various glittering ornaments, dress in brilliant stuffs, carry in their hand a musket, on their waist a sword, and on their head seven feathers like those of Simurq, and crying out with a voice like Modikarb and Malek Ushtur, put the columns of the army into motion.’

Evliya tells us that the procession was organised into fifty-seven sections and consisted of a thousand-and-one guilds, although the number of guilds which he actually describes is just seven hundred and thirty-five. Representatives of each of these guilds paraded in their characteristic costumes or uniforms, exhibiting on floats their various trades and enterprises, trying to outdo one another in amusing or amazing the Sultan and the other spectators.

All these guilds pass on wagons or on foot, with the instruments of their handicraft, and are busy with great noise at their work. The carpenters prepare wooden houses, the builders raise walls, the woodcutters pass with loads of trees, the sawyers pass sawing them, the masons whiten their shops, the chalk-makers crunch chalk and whiten their faces, playing a thousand tricks … The toy-makers of Eyüp exhibit on wagons a thousand trifles and toys for children to play with. In their train you see bearded fellows and men of thirty years of age, some dressed as children with hoods and bibs, some as nurses who care for them, while the bearded babies cry after playthings or amuse themselves with spinning tops or sounding little trumpets … The Greek fur-makers of the marketplace of Mahmut Paşa form a separate procession, with caps of bearskin and breeches of fur. Some are dressed from head to foot in lion’s, leopard’s and wolves’ skin, with kalpaks of sable on their heads. Some dress again in skins, as wild men and savages, so that those who see them are afraid, each one being held by strong chains and led by six or seven people, while others are dressed as strange creatures with their feet apparently turned to the sky, while they walk with their real feet upon the ground … The Bakers pass working at their trade, some baking and throwing small loaves among the crowd. They also make for this occasion immense loaves, the size of the cupola of a hamam, covered with sesame and fennel; these loaves are carried on wagons which are dragged along by seventy to eighty pairs of oxen. No oven being capable of holding loaves of so large a size, they bake them in pits made for that purpose, where the loaf is covered from above with cinders, and from the four sides baked slowly by the fire. It is worth while to see it … These guilds pass before the Alay Köşkü with a thousand tricks and fits, which it is impossible to describe, and behind them walk their Sheikhs followed by their pages playing the eightfold Turkish music.

Evliya tells us that there were several disputes concerning precedence in the imperial procession. The first of these quarrels was between the Butchers and the Captains of the White Sea (the Mediterranean). The Captains, having heard that the Butchers were slated to pass before them, assembled together and presented a petition to the Sultan, saying that they would be subjected to everlasting shame if their eminent guild was forced to parade behind the ‘blood-shedding’ Butchers. Sultan Murat settled the dispute in favour of the Captains of the White Sea, issuing this imperial edict: ‘Indeed, besides the fact that they supply the capital with provisions, they have also taken Noah for their protector. They are a respectable guild of men, who militate in God’s ways against the Infidels, and are well-skilled in many sciences. They may also pass in great solemnity, and then be followed by the Butchers.’

And so the Captains of the White Sea were moved up in the order of the imperial procession, and proceeded to put on one of the most elaborate and spirited displays seen that day, according to Evliya.

The Captains of the Caravellas, Galleons and other ships, having fired from them a triple salute at Saray Point, pour all their men on shore, where they place on floats some hundred small boats and drag them along with cables, shouting ‘Aya Mola!’ In their boats are seen the finest cabin boys dressed in gold doing service to their masters, who make free with drinking. Music is played on all sides, the masts and oars are adorned with pearls and set with jewels, the sails are of rich stuffs and embroidered muslin, and on the top of each mast are a couple of boys whistling tunes of Silistria. Arriving at the Alay Köşkü they meet five or ten ships of the Infidels, with whom they engage in battle in the presence of the Emperor. Thus the show of a great fight is represented with the roaring of cannons, the smoke covering the sky. At last the Moslems becoming victors, they board the ships of the Infidels, take booty and chase the fine Frank boys, carrying them off from the old bearded Infidels, whom they put in chains. They upset the crosses of the Infidel flags and dragging the captured vessels astern of their own ships, they cry out the universal Moslem slogan of ‘Allah! Allah!’ … Never before the time of Sultan Murat IV was there seen so brilliant a union of mariners.

After the Captains of the White Sea had passed with their entourage, the Butchers once again attempted to join the line of march, but their place was disputed by the guild of the Egyptian Merchants. The adversaries assembled before the Alay Köşkü and once again the Sultan decided against the Butchers, ‘to the great delight of the Egyptian Merchants, who, leaping for joy, passed immediately after the Captains of the White Sea’.

Then finally the Butchers were allowed to take their place in the procession, marching before the Men of the Slaughter-House and the Jewish Meat-Merchants, neither of whom would seem to have had any influence with the Sultan. ‘The Butchers, who are almost all Janissaries, pass clad in armour on wagons, exposing to public view in their shops, adorned with rich stuffs and flowers, fat sheep of Karamania weighing from forty to fifty occas. They trace on their white flesh figures with saffron, gild their horns, cut them up with their large knives, and weighing them in yellow-coloured scales, cry: “Take the occa for an asper, take it my soul, it is an excellent roast dish.” Thus chanting, they parade with their large knives and cutlasses, passing on foot in the procession.’

Still another quarrel over precedence took place between the Fish-Cooks and the Helvacıs, or sugar-bakers. As Evliya tells it:

The Emperor decided that the latter should go first, to the great annoyance of the Fish-Cooks, who appealed to their patron Jonah and blamed the Helvacıs, who reproached the Fish-Cooks, saying fish was very unwholesome and infatuating food. In proof they adduced what happened when the famous Yazıcı-zadeh Mohammed Efendi, the author of the Mohammedieh, sent his work in the year 847 (1443) to Balkh and Bukhara. When the doctors of those two towns were told that the author had written it on the seashore shut up in a cave, they decided that he could never have eaten a fish, because a man who eats much fish loses his intellect and never could have compiled so valuable a work. The disciples of the author averred the fact that neither he, his father, nor his grandfather had ever eaten fish. To this reproach the Helvacıs added the praise of the Helva contained in the Koran, and quoted the Prophet, who once said: ‘The faithful are sweet, the wicked sour.’ Having put forth their claims in this way in the Emperor’s presence, they carried the votes of the whole assembly that the precedence was due to them rather than to the Fish-Cooks, and accordingly obtained the imperial diploma.

Thus the Helvacıs took their place in the procession ‘fitting up their shops on litters with all kinds of sweets, which bring water into the mouths of the boys of the town, who devour them with their eyes. They exhibit on litters different kinds of confectionaries in basins, and perfume the brains of the spectators with amber scent. They produce at this public exhibition trees of sugar with sweets upon them, an admirable show! Behind them walks the Chief Confectioner of the Saray, followed by the troops of the confectioners playing the eightfold Turkish music.’

So they passed before the Alay Köşkü in turn, all of the guilds and corporations of Stamboul; tradesmen, artisans, merchants, labourers, civil servants, scholars, physicians, poets, musicians, entertainers, and functionaries of the religious, civil and military hierarchies of the Empire, all making a display before the Sultan and his court. And Evliya Efendi was there to describe them all in the most minute detail, including even the meanest and most insignificant of the guilds, omitting not even the lowly Gravediggers. ‘Five hundred Gravediggers pass with shovels and hoes in their hands, asking the spectators where they shall dig their graves, and set up in this way a warning for many. The Gravediggers acknowledge as their patron Cain, the son of Adam, who murdered his brother Abel for a girl’s sake. Not knowing how to hide the body, he saw a raven excavating with his beak a cocoa nut, in imitation of which he dug a grave to bury Abel’s corpse. He is buried on Mount Ararat, in the place where Adam’s kitchen stood. From that day Cain has remained the patron of all of those who shed blood and dig graves, as well as of the jealous.’

Even the poor madmen of the city were given an outing on this festive day, and Evliya describes their antics as they pass in the train of the Head Physician: ‘Three hundred keepers of the bedlams of Constantinople pass in the procession, leading several hundred madmen in gold and silver chains. Some of the keepers carry bottles in their hands from which they give medicines to the madmen, while others beat or box the fools to keep them in order. Some of them are naked, some cry, some laugh, some swear and attack their keepers, which puts the spectators to flight. If I were to describe all the fits of the madmen and fools on such a day of public procession, I should fill a book.’

Also represented in the procession were the Corporation of Beggars, numbering, according to Evliya, seven thousand with their Sheikh. ‘Relying on the text of the Koran: “Alms for the poor and wretched,” they pass in a great crowd of strange figures dressed in woollen cloth and turbans of palm-leaves, crying “Ya fettah!” (O All-Merciful), some blind, some lame, some having lost a hand or foot, some naked and barefoot, and some mounted on asses. They place their Sheikh in the centre, and after his prayer is performed they all cry together “Allah, Allah, Amen!” and the sound of this cry of seven thousand tongues rends the sky. This prayer is performed for the Emperor’s health immediately under the Alay Köşkü, where they receive alms.’

A shop on the Street of the Scale-Makers

Besides the reputable merchants, tradesmen, artisans and craftsmen of the city, the procession included less savoury groups, such as, as Evliya tells us: ‘The Corporation of Thieves and Footpads might be here noted as a very numerous one, who have an eye to our purses; but far be they from us. We say the same of the Corporation of Pimps and Bankrupts, who are innumerable. These thieves pay tribute to the two chief officers of the police, and get their subsistence by mingling in the crowds of Constantinople and by cheating foreigners.’

The next-to-last section in the procession was made up of the Fools and Mimics of Constantinople. According to Evliya: ‘Whenever there is a feast of imperial circumcision, nuptials, or victory, from two to three hundred singers, comics, mimics and mischievous boys of the town, who have exhausted seventy cups of the poison of life and misrule, crowd together and play, day and night. They are divided into twelve companies.’ The first of these companies were made up of young Gypsies and the last was composed of Jewish boys, and the two groups took turn in poking fun at one another as they marched along in the parade.

The twelfth company are two hundred Jewish boys, all tumblers, jugglers, fire-eaters, ball-players, and cup-bearers, who pass the whole night in showing their tricks, and ask more than one hundred piastres for a night’s performance. As these Jewish boys have the greatest antipathy to the Gypsies, who compose the first company, they generally set a band of these Jewish boys against a band of Gypsies, which produces the strangest scenes. Thus, they represent the play of a Jew surprised in flagrante with a Gypsy girl; the girl is seated on an ass and conducted through the street with nasty intestines on her head, which makes the people nearly die with laughing. In short these twelve companies of boys vie with each other in producing the most voluptuous dances and the most comical scenes. They are all dressed in gold stuff, and endeavour to excel while passing under the Alay Köşkü, where the Emperor is seated, so as to attract his attention with their fits and tricks. Since Adam descended from Paradise on earth, never was there seen such a crowd of tempting boys as under Sultan Murat IV.

The last guild in the procession was that of the Tavern-Keepers. Evliya tells us that in Istanbul there were ‘one thousand such places of misrule, kept by Greeks, Armenians and Jews. In the procession wine is not produced openly, and the Tavern-Keepers pass all in disguise and clad in armour. The boys of the taverns, all shameless drunkards, and all the partisans of wine pass singing songs, tumbling down and rising again.’ The last of all to pass were the Jewish tavern-keepers, ‘all masked and wearing the most precious dresses bedecked with jewels, carrying in their hands crystal and porcelain cups, out of which they pour sherbet instead of wine for the spectators.’

And so finally this fabulous parade came to an end as the last of the marchers passed the Alay Köşkü, ‘after which the guilds accompanied their officers to their lodgings and everyone returned home’. Evliya then ends his account by saying that ‘the procession of the imperial camp began its march at dawn and continued the whole day until sunset. On account of this parade all work and trade in Constantinople were stopped for three days, during which the riot and confusion filled the town to such a degree which is not to be expressed by language, and which I, the humble Evliya, only dared to describe. Nowhere else has such a procession been seen or shall be seen; it could only be carried into effect by the imperial orders of Sultan Murat IV.’ And then Evliya, obviously exhausted by his long description of the imperial procession, concludes with this remark: ‘Amen! By the Lord of all the Prophets; God be praised that I have overcome the task of describing the guilds and corporations of Constantinople!’

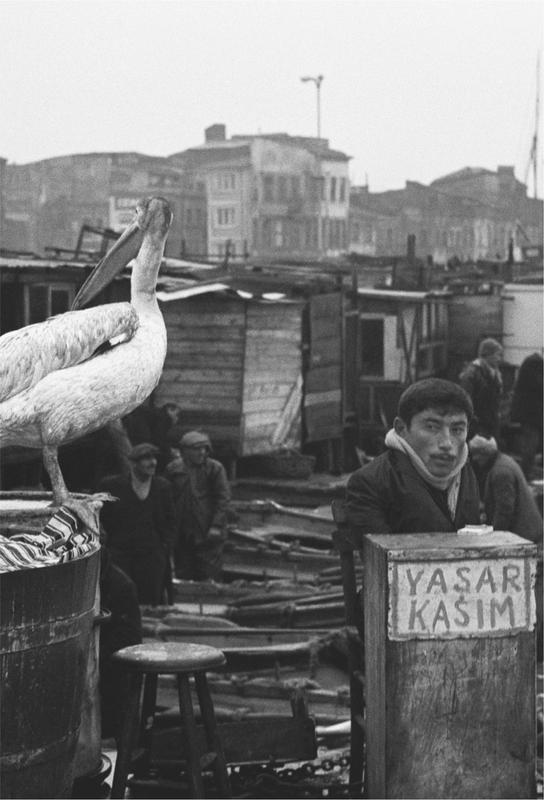

Yaşar Kasım and his pelican