Miss K. arrived at Ravensbrück on October 11, 1944, a few days shy of her thirty-sixth birthday. Every deportee was immediately given a number upon arrival, and Toto’s was 77370. Political prisoners had to wear red armbands, and hers bore an N for Niederländerin, or Dutch.

Built in 1938, Ravensbrück was the country’s largest detention camp for women—132,000 women were deported to Ravensbrück and 90,000 exterminated. The camp was situated fifty miles north of Berlin in an area of marshes and dunes swept by glacial winds. The temperature was so cold that the region was referred to as the “little Siberia of Mecklenburg.” Toto was imprisoned there for seven months until the camp was liberated by Allied troops in April 1945.

Like Dachau, Buchenwald, Auschwitz, Mauthausen, Sobibor and Treblinka, Ravensbrück was hell on earth, the very incarnation of barbarism and the representation of absolute and unimaginable cruelty. Toto had survived horrific and sordid conditions in Italy but nothing could have prepared her for what came next. She witnessed the construction of the camp’s gas chamber in early 1945 and of the second crematorium during the winter.

For a long time, the “undesirables” had been killed by lethal injection but the “turnover” was so great that the Nazis decided to use machine guns to eliminate the unfortunate women. Finding even this task too “tiring,” they unanimously opted for gas chambers. Toto would discover that the ashes from the crematorium were used as agricultural fertilizer and that newborns were killed at birth.

Miss K.’s group of detainees included other members of the Resistance: communists, ordinary prisoners, members of religious sects—such as Jehovah’s Witnesses—as well as gypsies and Jews. From the moment Toto arrived, she was assigned excavation work, a dreaded and dreadful task. The verfügbaren, as they were called, shoveled sand, unloaded trucks and repaired roads. The slightest weakness or moan would be met with a pummeling from the guards.

Waking up at 4:30 A.M., she had to fight to use the toilet facilities, a frightening undertaking in the crowded camp, before heading to a roll call that lasted three hours, regardless of the weather. In rows of ten, the prisoners had to remain still until they received the signal to go to work. Each exhausting workday was followed by an interminable wait for their daily food rations. Toto was worn to the bone. In the fall of 1944, prisoners were allotted two hundred grams (about seven ounces) of moldy bread and a cup of soup each day; it was not unusual to find pieces of rags and dirty bandages floating in the putrid broth. Sleep was nearly impossible. Two to four women shared a thirty-inch mattress, and many simply collapsed from exhaustion to the excrement-covered floor, still wearing their sweat-soaked clothes.

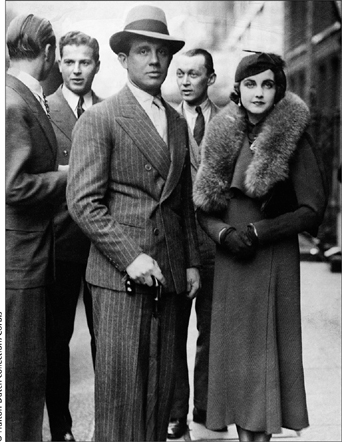

London, 1934. Toto was in London to shoot a film but soon gave up cinematic pursuits for the life of a femme fatale. Her espionage activities on behalf of the resistance during World War II resulted in her arrest by the Nazis.

© Sasha/Hulton Archive/Getty Images

The Koopman family in Java (on horseback, from left to right): Toto, her father Colonel Jan George Koopman, her mother Catharina, and her brother Henry, known as “Ody.”

Private Collection

Toto and her mother. Mrs Koopman was half-Javanese with Chinese ancestry and she and her children were considered “green Dutchmen,” a derogatory reference to the color of their skin. Far from feeling ashamed, Toto was very proud of her biracial heritage, an attitude that was quite rare for the times.

Private Collection

© Condé Nast Archive / Corbis

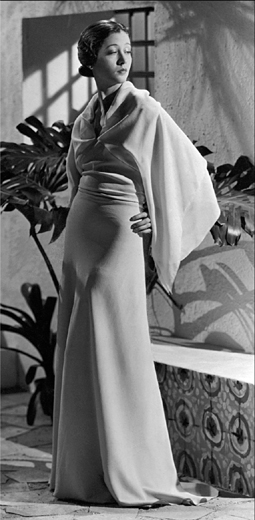

Toto poses for Vogue. Thanks to George Hoyningen-Huene, Toto became first biracial celebrity model. Today, Hoyningen-Huene’s iconic photographs of Toto are exhibited in museums, published in monographs and featured on postcards.

© Condé Nast Archive / Corbis

Alexis Mdivani–bogus prince but authentic rascal–and his wife, American heiress Barbara Hutton. The saga of the “Marrying Mdivanis” caused quite a stir during the 1920s and 1930s. Beautiful and free-spirited, Toto Koopman was Alexis Mdivani’s soul mate and siren. He would always have a special place in her heart. Alexis died in a gruesome car accident in 1935, at age thirty.

© Hulton-Dutch collection / Corbis

Toto Koopman and Douglas Fairbanks on the set of the Alexander Korda film The Private Life of Don Juan (1934). This is a rare photo, as all of Toto’s scenes were left on the cutting room floor.

© Rue des Archives / BCA

Toto Koopman in Vogue. Wearing creations by Madeleine Vionnet and Augustabernard, Toto Koopman embodied the aspirations of a new generation of women. The gowns clung to the body like a second skin, making it impossible to wear undergarments. To avoid indecency, Toto powdered her breasts and pubic area so that the fabric would not cling to those parts of her body.

© Condé Nast Archive / Corbis

Toto Koopman (right) and Tallulah Bankhead attend the London premiere of The Private Life of Don Juan in 1934. The two women had a brief and intense romance. “My father warned me about men and booze, but he never said anything about women …” Bankhead would respond when asked about her bisexuality.

© Hulton-Dutch collection / Corbis

Lord Beaverbrook, press baron and one of the most powerful men in Great Britain, with his son Max Aitken. Toto Koopman had affairs with both men, which caused a major scandal.

© Time & life pictures / Getty Images

Randolph Churchill, son of Winston. Years after his affair with Toto, Randolph Churchill was the first to come to her aid when she was released from the Ravensbrück concentration camp.

© TopFoto / Roger-Viollet

In 1938, Toto Koopman sat for her friend the painter Joseph Oppenheimer, who had escaped Nazi Germany and come to live in London. “If a portrait can accurately capture one’s personality, [Oppenheimer] presents Miss Koopman as a beautiful and alluring woman whose expression reveals a slight disdain mixed with curiosity, a proud reserve and an inherent reticence.”

© Painting by Joseph Oppenheimer R. P. reproduced by permission of the Joseph and Fanny Oppenheimer Foundation

Lady Deirdre Curteis (then Lady Grantley) met Toto Koopman in 1959. The English aristocrat was young enough to be her daughter, and the two shared a deep friendship until Toto’s death.

Private Collection

A portrait of Toto Koopman drawn by a fellow prisoner in Ravensbrück concentration camp, 1944. There is no trace of the splendid and proud woman who posed for Joseph Oppenheimer one year before the war. Toto would keep this piece of cardboard for the rest of her life.

Private Collection

Toto Koopman (left) and Elisabeth Eichmann. The two women met in Italy during the war and attended a Fascist rally where they both posed as sympathizers. “The Black Shirts had no idea that [Toto] was taking mental notes in order to write up a report for the Italian Resistance and the British Government,” Eichmann recalled.

Private Collection

Toto Koopman (left) and Gala Barbisan on the Lido beach, in Venice, summer 1954. Co-founder of the Prix Médicis, Barbisan, a “White Russian,” attracted writers to her salons in France and Italy.

Private Collection

Robert Heber-Percy, known as the “Mad Boy.” He could be wildly generous or mercilessly cruel, and his violent mood swings justified his nickname. He enjoyed Toto’s friendship (a great deal), and the feeling was mutual.

Private Collection

Toto Koopman on an archaeological dig in the Taurus Mountains in Turkey, summer 1953.

Private Collection

Toto Koopman (left) and Erica Brausen, photographed by their friend Willy Maywald at their home in Panarea, summer 1967.

© Association Willy Maywald © Adagp, Paris 2001

Erica Brausen at the Hanover Gallery. “It was a place where the creative spirit was always alive and where one could see the most brilliant artwork of the time,” said Peter Brook.

© TopFoto / Roger-Viollet

Francis Bacon. Erica Brausen discovered Bacon in 1946, when he could not sell any of his paintings and no gallery wanted to show his work. She took the risk of representing him and promoted his career. But he would eventually betray her and leave her gallery.

© Jorge Lewinski / TopFoto / Roger-Viollet

The foul smell was unbearable; vermin infested bodies and epidemics were the prisoners’ worst enemies. As one survivor described it: “In the bunks, the sick ones relieved themselves in their beds, too bad for their bunkmates below; the bedding was never washed and we lived with absolute stench, without any hygiene, without any care.”11 The prisoners were on alert even as they slept. “At night, we slept on our shoes that were often filled with snow … and with our bread. But still, we often woke to find that everything had disappeared and we would show up at the Appell with empty stomachs and bare feet, and for that we were beaten.”12

Sterilizations were performed on dozens of prisoners, including little girls, during the winter of 1944 to 1945. The victims were mostly gypsies, but Toto Koopman always maintained that she had been subjected to the experiments. In a letter to her friend Elisabeth Eichmann dated August 15, 1946, in which she discussed her hopes of resuming a normal love life one day, she said that, for the time being “it makes no difference to me at all as I am still impotent from the sterilizing projects of the camp.”13 She spoke of this episode over the years with some modesty but without the slightest ambiguity.

From the moment she arrived, walking past the double rows of SS men and women holding back their German shepherds, from the moment her head was shaved, Toto was prepared for the worst, but daily life at Ravensbrück went beyond anything she could have imagined. “I would have rather been shot immediately!” she often told her friends. Endless roll calls at dawn, even in the snow, prisoners in tattered dresses and barefoot inside their galoshes, dysentery from the polluted water, long lines to use the toilet facilities, which consisted of wood planks with twenty holes in them, not to mention the mood swings of the guards who would kick and beat the prisoners without the slightest provocation. The list of abuses was endless.

At first, Toto turned to faith and prayers to get through her days at the camp. This may seem surprising, as it does not conform to her image as a bisexual vamp. However, her nephew, Robbert J.B. Koopman, pointed out that while their family was Protestant, his aunt converted to Catholicism because she could relate more easily to that religion. “Toto also believed that if one managed to stay clean by washing with one glass of water each day, one could maintain one’s dignity and self-esteem. If not, it was certain death,” recalled Lady Deirdre Curteis.

Toto’s friends maintained that she survived thanks to, curiously, the garlic and onions that Randolph Churchill sent her. Prisoners could receive packages addressed to them with their first and last names, numbers, block numbers and the address of the camp: “Ravensbrück, near Fürstenberg, Mecklenburg, Germany.” Knowledgeable about nutrition, Toto recognized that onions and garlic had protective health qualities and could help to ward off sickness. They facilitated the dilation of blood vessels, improved circulation and were an excellent intestinal disinfectant. She believed their antiviral and antibacterial properties protected her from severe illness. Toto claimed Randolph’s packages saved her life, and she shared their contents with her fellow prisoners. “When the mail did not come, Toto would exchange her bread rations for onions that were available in the kitchens,” added Malitte Matta.

Realizing that she could not endure this existence—especially when the temperatures dropped to minus 27°F during the winter of 1944 to 1945—Miss K. decided to take a chance. What did she risk? Death? Death would be a true deliverance compared to life in the camp. Toto knew, for example, that she might, at any given moment, be assigned to the Scheisskolonne, the “column of shit,” and the thought paralyzed her with fear. Those unfortunate prisoners had to pick up excrement, press it down with their bare feet and spend entire days in the sewage pit. With their bare hands, they had to mix the vile stuff with the still-warm ashes from the crematorium to form balls that, once dry, would be used as fertilizer. If a prisoner had the misfortune to slip in the midst of this filth, the Nazis set their dogs loose to tear the prisoner to pieces.