chapter 7

england’s green and pleasant land

—“Jerusalem”

In early July 1922, Robeson, age twenty-four, arrived in Southampton and said, “I had never seen any land so beautiful—green and com-panionable.” He continued, “The people were so kind…. I sensed none of the prejudice I had left.” In most of America, Jim Crow laws prevailed, and people were segregated on trains and streetcars, in taxis, at gas stations, and in waiting rooms. A handshake could happen between a black person and a white person only if the white person offered to shake hands, which they often didn’t.

When Robeson had played pro football in Akron, Ohio, shortly before going to England, the crowds had booed him. He and Fritz Pollard, an All-American black halfback from Brown University, had not been able to get a hotel room or eat in a restaurant. After one game in Green Bay, Wisconsin, where nearly all the policemen were members of the Ku Klux Klan, they were called out of a dining room and told, “We don’t allow colored people to eat in our hotel.”

In England Robeson received a “friendly welcome” and was treated with courtesy and respect. He was regarded as a “gentleman and a scholar.” “My background at Rutgers and my interest in academic studies were given much more weight than such matters are given in America,” he recalled. “I found in London a congenial and stimulating intellectual atmosphere in which I felt at home.”

Essie had remained in New York, supposedly to continue her job at the pathology lab in the hospital. She hadn’t told Robeson that she needed surgery to remove adhesions from an old appendectomy. Essie was sure that if Robeson knew about the operation he would want to stay with her and would miss his opportunity.

After seeing him off at the pier, Essie wrote twenty-one letters to him, asked one of his friends at Columbia to mail them to Paul at regular intervals, and checked herself into New York Presbyterian Hospital.

Robeson began rehearsals with Mrs. Patrick Campbell. Mrs. Pat, as she was called, had renamed the play, changing Taboo to Voodoo. She not only starred in the show, but also directed it and rewrote sections of the script. Without knowing that Essie was hospitalized, Robeson sent her cheerful reports. “The play is shaping up fine,” he wrote. They planned to try out Voodoo in the provinces, English counties outside of greater London, and also in Scotland, to prepare for a London production in August.

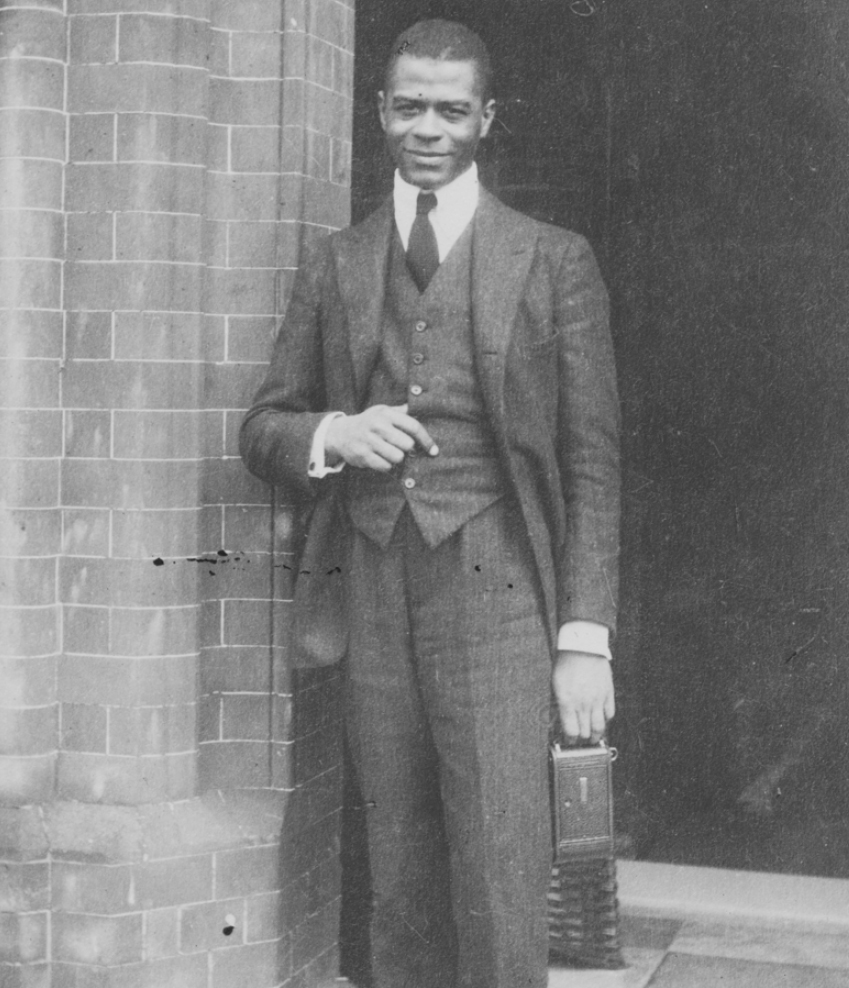

Robeson in costume for Voodoo during the 1922 British tour

On July 17, Voodoo opened in Blackpool, a seaside resort. The audience hurled oranges at the actors, who ran offstage. The play received poor reviews and Robeson began to worry. “To be truthful, things are none too rosy,” he wrote to Essie. “Mrs. Campbell doesn’t know her lines too well. But I guess we’ll hit.” Still, Robeson considered his options. “I think that if this does not turn out as well as I expected, I’d better head right back and get down to law,” he wrote. “Of course, if the play goes, I’ll stay; but if not, I think I’d better come back.”

The next stop on the tour was Edinburgh, Scotland. Actors on tour couldn’t afford regular hotels so they stayed with working-class people who took in roomers. Many young actors resented these “digs,” which were located in factory neighborhoods. Not Robeson. He enjoyed living with “labouring folk” and appreciated their “warmth and friendliness.” His lifelong love of British working-class people and their songs began on this trip.

Voodoo received a better reception in Edinburgh. The audience was enthusiastic, mainly because of Robeson. During a scene as a wandering minstrel, Robeson was supposed to fall asleep and start whistling as he lapsed into a dream. Since he couldn’t whistle, he hummed. Mrs. Pat, standing in the wings, whispered, “Sing it louder, sing it louder.” Robeson spontaneously sang “Go Down, Moses” followed by another spiritual. “I was merely singing songs I had learned in church,” he said, “and I was staggered to read the criticisms and find I was famous!”

“The audiences loved ‘Old Black Joe,’ thinking it was a Negro spiritual,” he said. However, the wistful song had been composed by Stephen Foster in the nineteenth century. From then on, whenever things didn’t go right in a performance, Mrs. Pat told Robeson to sing. And he did.

By the time they performed in Glasgow, the play had quickly “turned into an unaccompanied concert—with some dramatic action,” he recalled. To Essie, he wrote, “It is the consensus of opinion that the most enjoyable feature of the show is my singing. Mrs. Campbell is very unselfish. She’s always saying when we take our bows at the final curtain:…‘it’s your show, not mine.’ And she says: ‘Sing a lot and long—more, more.’ ”

Mrs. Campbell told Robeson that she thought he was a “real artist” and suggested that he would make “a marvelous Othello.” He bought copies of Shakespeare’s plays to study. He also began thinking seriously about staying in London after Voodoo opened there, to try his luck as an actor.

In his letters to Essie, Robeson urged her to join him. He told her how much he loved and missed her. “So anxious for you to see me and criticize,” he wrote. “Know you can help me.” He discussed choices for their future and asked for her advice. “I don’t want to send for you and then be out of work,” he wrote.

Before going down to Plymouth, the last stop on the tour, Robeson returned to London. Black communities in the city had been growing since the end of World War I, with students arriving from Africa and the Caribbean to continue their education. “London was the center of the British Empire,” wrote Robeson, “and it was there that I ‘discovered’ Africa. That discovery…has influenced my life ever since.”

Robeson stayed at the home of John C. Payne, a friend from Harlem who welcomed black visitors, especially musicians and performers. Payne had come to London to sing baritone in a quartet that performed spirituals and popular songs. He decided to live there permanently to escape the racism he had encountered in America.

At Payne’s “flat,” Robeson met another American guest, the pianist Lawrence Brown, who had recently completed a European tour accompanying the celebrated black tenor Roland Hayes. Brown was born and raised in Jacksonville, Florida. His grandfather had been enslaved. Like Robeson, Brown had lost his mother at an early age. As a child, he had witnessed the horror of lynchings and vowed never to return to racist America. Yet he valued and honored his heritage and wanted to preserve every detail of Negro music. When Robeson met him, Brown had published the first of his arrangements of well-known spirituals such as “Steal Away,” and was working on a second volume.

Lawrence B. Brown in the early 1920s, around the time he met Paul Robeson. They soon became musical partners.

Steal away, steal away, steal away to Jesus

Steal away, steal away home

I ain’t got long to stay here

Robeson was deeply impressed by Brown’s serious research and his creative interest in African American folk music. He said of Brown, “It was this musician who clarified my instinctive feeling that the simple, beautiful songs of my childhood, heard every Sunday in church and every day at home and in the community…should become important concert material.”

One night, “just for fun” at a party, Robeson sang with Brown at the piano. “He had the most magnificent natural voice,” recalled Brown. “I knew at once that it was possible for him to become a great singer, but I had no idea then that we would ever work together.” After a few days, Robeson left for Plymouth. “Cheerio, old chap,” said Brown, and promised to look Robeson up if he ever went back to the States.

Robeson returned to Voodoo, but things weren’t going well. Mrs. Pat kept forgetting her lines and improvising. She was known to be high-strung and unpredictable, and she delighted in making stinging remarks to the actors. Now, she turned on Robeson, and rather than encourage him, as before, she instead became nasty. His success and good reviews had aroused her jealousy. When critics praised him as the “dominating personality in ‘Voodoo,’ ” she became angry and began losing interest in the show.

Robeson doubted that a London production would happen and thought about what he should do. He wrote to Essie, asking her opinion: “You’ll know what to do…. You always know.” But her letters seemed indifferent. Puzzled, he wondered why she never responded to his questions directly. Finally, in August, he sent her a cable: “All my questions unanswered. Worried. Is anything wrong. All love, Paul.”

By then, Essie had been in the hospital for a month. Complications had set in after her surgery and she had come down with phlebitis, inflammation of a vein. She sent Robeson a cable and told him the truth. When he received the news, he was “taken absolutely off-guard.” “I cried and cried as tho my heart would break,” he wrote to Essie. “I couldn’t pull myself together.” He wanted to return to New York immediately, but she told him to stay, thinking she might get well enough to join him.

Just then, Voodoo closed abruptly in Plymouth. There would be no London production. Robeson booked passage and sailed to New York. As soon as he docked, he rushed to the hospital. With his loving care, Essie quickly improved and was soon able to go home.

But the experience of living and working in England, and being treated with respect, had been a revelation. Robeson realized that the world offered him new possibilities as an artist and as a man. He was discovering the power of his magnificent voice.