chapter 9

the walls came a tumblin’ down

—“Joshua Fit De Battle Ob Jericho”

Robeson’s success with the Provincetown Players attracted the attention of artists, activists, and even a movie producer. Oscar Micheaux, America’s first black feature filmmaker had his own company, and he asked Robeson to star in Body and Soul. Micheaux wanted to make uplifting black dramas in urban settings. In 1924, movies were silent, so Robeson couldn’t use his superb voice. But he accepted the part Micheaux offered because it gave him a big salary of one hundred dollars a week ($1395 in today’s dollars) for three weeks of shooting.

In the movie, Robeson played the dual role of an evil convict posing as a preacher, and his sincere, virtuous twin brother. Some scenes in-volved his playing both parts, so he had to switch personalities within minutes. Micheaux, a novelist turned producer, wrote, directed, and distributed his movies. He made “race films” intended for black audiences, and Body and Soul played only in theaters attended by blacks. Robeson disliked the melodramatic film and never spoke about it, but Essie was pleased with his earnings, a total of three hundred dollars. She had given up her job at the lab and now managed his career.

Once again, Robeson waited for a good project to come along. He said, “I realized even then that the number of roles I might ever be able to act were so few, and so far between, that I might starve to death no matter what the critics said about me!” Movie studios cast black actors as servants: maids, cooks, butlers, and bellboys. And black male characters were portrayed as lazy, stupid nitwits. Actor Lincoln Perry, known as Stepin Fetchit, earned a fortune playing a shuffling simpleton. Robeson despised these degrading roles.

He turned down an offer to appear in Lulu Belle, a play about Harlem street life. Essie urged him to take it, but Robeson thought the black stereotypes were beneath him. The shady characters of the melodrama did not represent the Harlem people he knew and respected.

By now, Robeson was a well-known actor in New York. He and Essie were invited to parties, and they mingled with an interracial group of leading figures in the arts and politics. Whenever he had the opportunity, at parties or friends’ houses or even on street corners, he sang. It was singing he loved most. One of his friends said, “Paul’s voice was like something from another world—sweet—if you can talk about a man’s voice being sweet.”

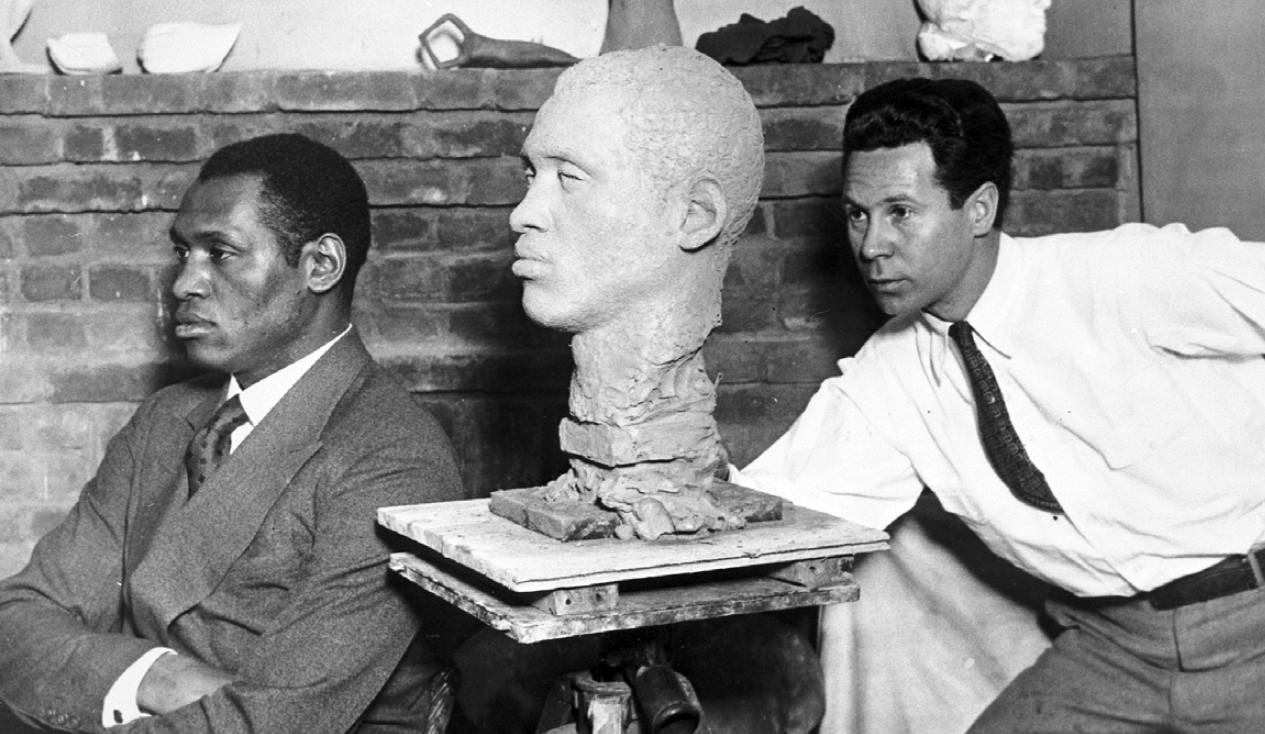

Sculptor Antonio Salemme had met Robeson during the rehearsal period of The Emperor Jones. After seeing the play, he asked Robeson to pose in his Greenwich Village studio. Salemme said of Robeson, “He had this presence, which was both dignified and disarming at the same time.”

Robeson posing for sculptor Antonio Salemme in his Greenwich Village studio in the 1920s. Over a period of two years, Salemme created many sculptures of Robeson, including a larger-than-life nude statue entitled “Negro Spiritual.”

For a nude sculpture, Salemme placed Robeson in a standing position and said, “Just think of ‘Deep River.’ ” Robeson would raise his arms and start to sing. His voice was so beautiful that Salemme didn’t know whether to work on his sculpture or just listen. Robeson said to Salemme, “I enjoy singing to you. You seem to get more than the voice, the music, the words; you know what I’m thinking, what I mean, what I feel when I sing.”

While he posed, Robeson tried out songs he was learning and experimented with various vocal effects. He discussed his concerns and goals. “If I can teach my audiences who know almost nothing about the Negro, to know him through my songs and through my roles,” he said, “then I will feel that I am an artist, and that I am using my art for myself, for my race, for the world.” Salemme titled the bronze statue of Robeson “Negro Spiritual.”

The two visited galleries so that Robeson could learn more about visual arts. Sometimes, when Robeson arrived for a sitting, he seemed depressed. One time, Salemme asked him what was wrong, and Robeson said, “I went to see an old friend of mine uptown, and I had to take the freight elevator.” Racial slights hurt Robeson, but he held his anger.

During the run of The Emperor Jones, Walter White and his wife attended a performance. White was blond, fair-skinned, and black. His great-grandmother had been enslaved, and she had borne children fathered by her master, William Henry Harrison, the future president. White used his unusual appearance to pass as white so he could investigate gruesome lynchings and race riots in the South. Back in the North, he gave speeches and lobbied to initiate legislation that would end the hideous crimes.

After seeing Robeson in The Emperor Jones, White and his wife planned to have dinner with Robeson and Essie. “We wanted supper and a place to talk,” recalled White. “Place after place was suggested and discarded” because of discrimination. They couldn’t find a good restaurant where they would be waited on. The two couples decided not to spoil the mood of the evening with a nasty confrontation, but instead rode a bus uptown to Harlem so they could be served without “fear of insult.”

White and his wife invited Robeson and Essie to interracial gatherings in their home in Harlem. White was one of the leaders of the Harlem Renaissance, a flowering of cultural activity that showcased black writers, visual artists, musicians, and performers. New York was the hub for theater and publishing, and Harlem, attracted artists and writers. A new appreciation had developed for the contributions to America from black men and women. Robeson expressed the spirit of the Harlem Renaissance when he said: “It is through art we are going to come into our own.” Artistic achievement, rather than political action, he believed, would advance racial justice.

Poet Langston Hughes said, “The 1920s were the years of Manhattan’s black Renaissance. It began with Shuffle Along…a honey of a show.” Because of music in theaters and nightclubs, and serious plays such as The Emperor Jones, “white people began to come to Harlem in droves,” wrote Hughes. “It was a period when, at almost every Harlem upper-crust dance or party, one would be introduced to various distinguished white celebrities there as guests.”

At a party hosted by White, Robeson met Carl Van Vechten and his wife. Van Vechten was a white writer and photographer who passionately supported black cultural figures. He helped Langston Hughes publish his first collection of poetry with his own publisher, Alfred A. Knopf. Van Vechten wrote pieces in mainstream magazines like Vanity Fair to promote the work of black artists.

Robeson and Essie attended another party at Van Vechten’s elegant apartment two weeks later. The gifted circle of guests included composer George Gershwin and publisher Alfred Knopf. This time, Robeson sang. Van Vechten wrote to a friend that seeing Robeson “singing spirituals is really a thrilling experience.”

Occasionally, Robeson sang at a few small concerts and private parties. One evening in March 1925, he bumped into Larry Brown, the musician he had met in London. Brown had returned to America to see his dying father in Florida. After the funeral, Brown traveled to Harlem to stay with friends. He dropped off his luggage and went out for a walk. “There, standing on the corner of 135th and 7th Avenue—alone—in front of the bank, was Paul Robeson.” Robeson invited Brown to go to Greenwich Village with him to visit his friend, Jimmy Light, the director of the Provincetown Players. “He [Robeson] said we might play some songs,” recounted Brown. That night, at Light’s apartment, Robeson sang two of the spirituals that Brown had arranged: “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot,” and “Every Time I Feel the Spirit.” Brown accompanied Robeson on the piano, and joined in as “the second voice.”

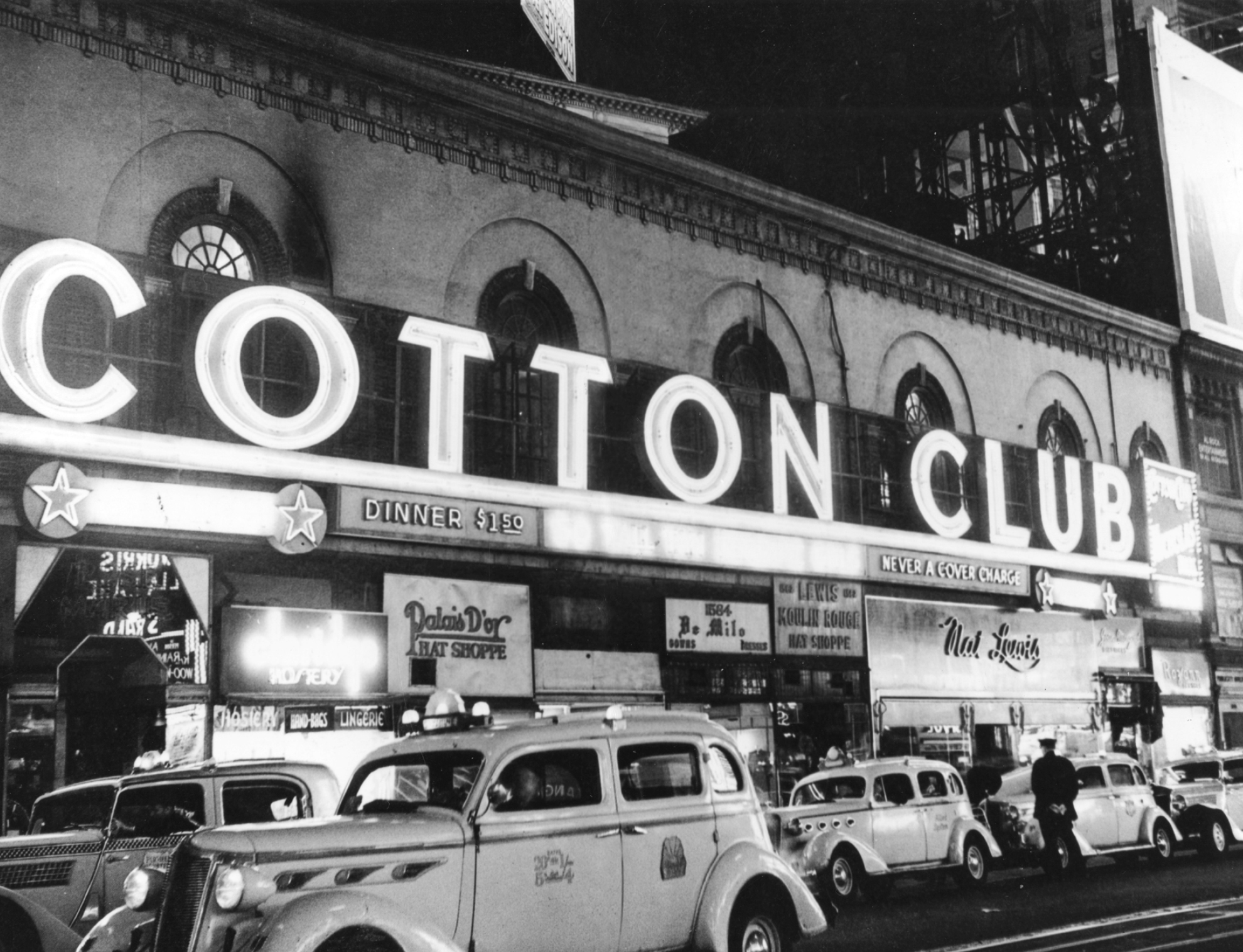

Taxis lined up in front of Harlem’s famed Cotton Club in the 1920s, to drop off and pick up passengers who had come to hear Duke Ellington’s band. During the years of the Harlem Renaissance, people flocked to Harlem to visit the jazz clubs.

A card from the Cotton Club that was saved and treasured. The entertainers and staff pictured on the card were African American. However, the Cotton Club catered to white patrons only. Black people could work there but were not admitted as guests.

“It was completely spontaneous,” remembered Brown.

The spirituals came from “the most humble of our people,” Robeson said, and had “abiding beauty.”

Light was enthralled. “Why don’t you fellows give a concert?” he suggested. With Essie, they went back to Light’s apartment and “threshed out the concert idea.” Robeson and Brown would split their earnings fifty–fifty, and each would give Essie ten percent as their agent.

From then on, Robeson and Brown sang spirituals at Van Vechten’s glamorous gatherings. Essie noted that Van Vechten “begged for more and more songs.” He offered to help them arrange a public concert and wrote letters to influential friends to publicize the event. “We all promoted Paul, his talent was so obvious,” said one of the Provincetown Players. This group gave Robeson and Brown use of their Greenwich Village Theater free of charge to hold the concert, set for April 19, 1925. The musicians had only three weeks to prepare. “We chose what we felt were the most beautiful of the spirituals,” said Brown.

The concert marked the first time that a black soloist, rather than a choral group, presented a program of “all-Negro music” at a recital for a racially mixed audience. In the late nineteenth century, the Fisk Jubilee Singers had introduced spirituals and secular songs in concerts to raise money for Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. By the early 1900s, though, many members of the group had dropped out, leaving barely enough of them to continue performing.

Robeson and Brown worried about how their songs would be received. Would New Yorkers understand the emotions expressed in the lyrics? “They were both very nervous,” wrote Essie in her diary the night of the concert. “When the boys appeared, there was thunderous applause, lasting three minutes. Then they sang.”

The program contained four sections, beginning with “Go Down, Moses.” The words came from the Old Testament. Enslaved people had taken the biblical texts that related to their own experiences:

When Israel was in Egypt land

Let my people go

Oppressed so hard they could not stand

Let my people go.

At the end of the song, the roar of enthusiastic applause startled Robeson and Brown so much that they forgot about their personal worries and just sang spontaneously.

Next came “I Don’t Feel No Ways Tired”:

For I hope to shout glory

When dis’ worl’ is on fire

Chillen, O glory Hallelujah!

Robeson had sung these spirituals at church every Sunday. Men and women in the congregation had rocked their bodies to the powerful rhythms. New Yorkers responded too, swaying in their seats.

The second part of the program consisted of folk and dialect songs including “Water Boy” and “Li’l Gal.” The dialect songs contained African American ways of speaking and spelling words that differed from standard English, and they had been performed in minstrel shows. Robeson had sung “Li’l Gal” at the Plantation Club in Harlem and had always liked it. Now he was bringing the tune to the concert stage, softening and lowering his voice to interpret the wistful love song:

I’s a sighin’ for you honey

And I never knows no rest

Li’l gal, li’l gal, li’l gal, li’l gal.

Robeson changed the mood as he performed spirituals that Brown had arranged, such as “Steal Away” and “Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child.” Robeson had said, “If I can recreate for an audience the great sadness of the Negro slave in ‘Sometimes I Feel Like a Motherless Child’…then I shall increase their knowledge and understanding of my people.”

And he did. Men and women wiped away tears. Essie said, “After each number, the applause was deafening.”

The duo ended the program with “I’ve Got a Home in-a-dat Rock,” and the rousing “Joshua Fit De Battle Ob Jericho.” The enraptured audience shouted and stamped. “The boys got curtain call after call,” said Essie. Robeson’s spirituals brought down the house, just as Joshua’s army had crumbled the walls of Jericho with trumpets and shouts. He was astonished by the response to his music. “I simply couldn’t understand it,” he said. “I didn’t sing these spirituals in any tradition, because I didn’t even know any tradition. I knew the songs from the time I was a child and they were mostly songs sung in unison by a lot of people. I just sang them as I felt their meaning.”