chapter 14

feel the spirit

—“Every Time I Feel the Spirit”

Paul Jr. wrote that his parents worked together again “as a professional team,” discussing Robeson’s career options and programs. However, Robeson’s lawyer Bob Rockmore was now his manager and controlled the finances and contracts. The new arrangement gave Robeson the freedom he needed.

On December 5, 1932, he jotted a note to himself: “Am terribly happy at No. 19 [Buckingham Street—their flat]…I feel so ambitious. Want to work all day at something.” He was adding songs in Russian, German, French, Dutch, Hungarian, Turkish, and Hebrew to his repertoire. At home, he listened to records. “Unquestionably Russian songs are right—most right for me,” he said, because he felt an emotional connection to them.

Bursting with new ideas, he was also eager to learn African languages. In January 1933, he and Essie enrolled at the University of London. He did comparative work in African linguistics, while she took courses in anthropology with a focus on African cultures. Robeson talked of visiting Africa. “I am proud of my African descent,” he told an interviewer.

“I am learning Swahili, Tivi, and other African dialects—which come easily to me because their rhythm is the same as that employed by the American Negro in speaking English.” When he started studying West Coast dialects, such as Ewe, Efik, and Hausa, he heard sounds he recalled from childhood. The pitch and pattern of tones reminded him of the “Negro English” dialect that was spoken when he was a boy. It was “like a home-coming,” he said. Robeson was excited about discovering his heritage and wanted to inspire black people to feel the same pride. Culture, he believed, would express black values and bring about change.

He agreed to do a revival of O’Neill’s play All God’s Chillun Got Wings. It came about when actress Flora Robson moved into a flat across the hall from the Robesons and they all became good friends. Robeson recreated his role as the black law student in this London production. Flora Robson took the part of his racist white wife. Robson had trained at the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art in London, and in 1931 she joined the prestigious Old Vic Theatre Company. The Old Vic was a not-for-profit theater that put on Shakespearean plays as well as operas, ballets, and artistic experiments. Robeson thought that working with such an accomplished actress would be a learning experience for him—and it was.

Robeson and Flora Robson in a scene from the 1933 London production of All God’s Chillun Got Wings

He was so dedicated to the project that he agreed to take a lower salary than usual of only ten pounds (fifty dollars) for the entire run of the show. Chillun opened at the Embassy Theatre on March 12, 1933. “People almost fought to get seats,” recalled his friend, Marie Seton. The run was extended, and every performance was sold out, even the standing room area. The director marveled at the way the two stars connected onstage. “A perfect dramatic partnership,” wrote the Observer. A reviewer for the News-Chronicle said, “Flora Robson…makes you forget she is acting. Of Paul Robeson, I am never sure if he is acting, but is just himself.” Robeson took criticism seriously. Despite any praise he received, he realized that he had “a long way to go on the painful journey from performing actor to theatrical artist.”

Social problems also concerned Robeson. The Great Depression had spread to the United Kingdom, where it was known as the Great Slump. More than three million people lost their jobs and depended on doles, payments they received from local governments. Industrial areas were especially hard hit. Robeson had performed Othello in these towns and knew the people. As a younger actor touring with Mrs. Campbell’s repertory company, he had stayed in workers’ homes. In Manchester, a textile center, he spoke with a worker whose father and grandfather had woven cotton picked by enslaved people in America. The workers had supported abolishing slavery during the Civil War. Robeson thought about these ties with British laborers. He had sung with unemployed Welsh miners and connected with them. “My whole social and political development was in England,” he said years later.

In London, he had met outspoken socialists, such as H. G. Wells. Listening to Wells in 1933, Robeson heard new ideas about a society that would abolish class distinctions, and an economic system in which workers would share profits cooperatively. he said he had “never really thought about Socialism,” said Robeson. The theories appealed to him.

While Chillun ran at the Piccadilly (where it transferred from the Embassy Theater), several thousand Jews landed in London as refugees from Nazi Germany. Adolph Hitler had become Chancellor of Germany and had started attacks on Jews, communists, homosexuals, Jehovah’s Witnesses, and the Roma people (often called Gypsies), labeling them enemies of the state. On April 1, 1933, he passed laws banning Jews from businesses, professions, the arts, and schools. German Jews fled in fear of being beaten to death or imprisoned.

At an exhibition of twentieth-century German art in London, Paul Robeson and Larry Brown perform in aid of German artists banned by Hitler. A triptych, Reflecting Darkness by Max Beckmann, hangs on the wall behind the piano.

Marie Seton asked Robeson to help the refugees by giving a benefit performance of Chillun. At first, he refused, saying “I’m an artist…. I don’t understand politics. I’ve avoided controversies.” But then he mulled it over and thought about how the plight of Jews in Germany was like that of African Americans, as captured in “Go Down, Moses”—Let my people go. He had always understood the meaning of those words.

Robeson agreed to perform a special matinee of Chillun, with which the actors raised two thousand pounds (about ten thousand dollars) for the refugees. Later, Robeson said that this was his first political act as an artist.

Chillun closed because Robeson had committed to shoot a film version of O’Neill’s play The Emperor Jones. In May 1933, he and Essie traveled to New York for the production. “Talkies” (movies with sound) were new, and for the first time, his voice would be heard in a movie.

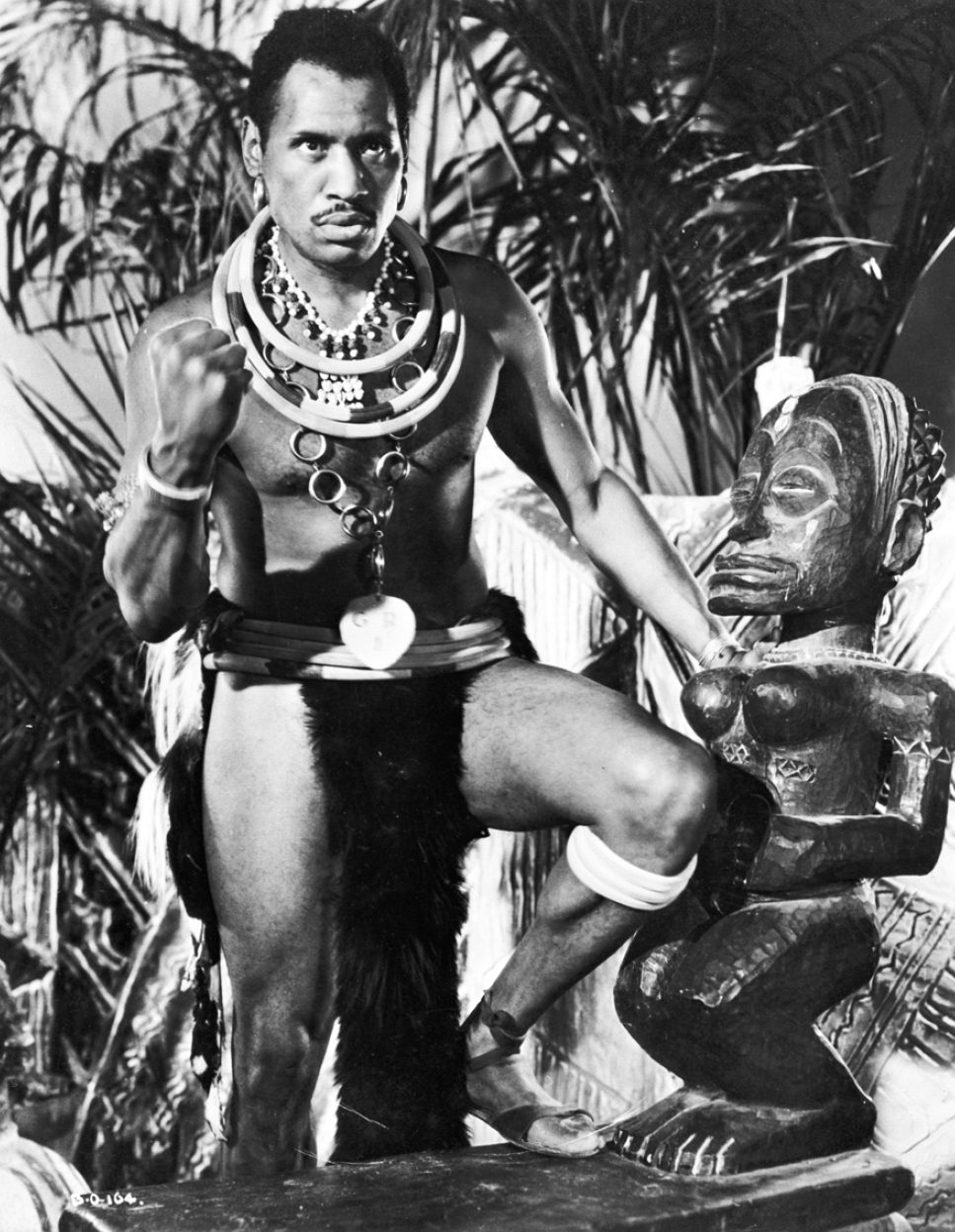

Robeson, playing Brutus Jones, a chain gang prisoner, tries to escape in the movie version of The Emperor Jones.

Although part of Jones was set in Georgia, Robeson insisted that he would not film in the segregated South. Spoken as well as unspoken Jim Crow laws prevailed in the southern states. Black people could not occupy the same sidewalk as white people, and they had to step off the curb when they passed a white person. Racial violence had increased during the Great Depression. White people competed for jobs usually held by minorities and in some cases murdered black workers in order to take their places. In 1933, the number of lynchings surged from eight to twenty-eight in a total of eleven states, including California, Maryland, and Missouri. Most lynchings were prompted by accusations that black men had insulted white men, or tried to register to vote, or simply looked at or spoke to a white woman. An alleged crime was enough to drive a mob to a public act of racial terrorism. Women were lynched too, such as the Alabama schoolteacher who scolded white children when they threw rocks at her.

Given these circumstances, Robeson held firm and refused to film the movie in the South. The producer begged him to reconsider, asking Robeson to at least shoot the jungle scenes in Charleston, South Carolina. At first, Robeson agreed to do it if he could stay in the best hotel in Charleston. But the manager said, “If I allow a Negro in this hotel, I might as well burn it down.” So Robeson filmed Jones at New York’s old Paramount Studio Complex in Astoria, Queens. The producers built an artificial jungle and swamp and heated the water so that Robeson wouldn’t catch one of his frequent colds. For the scene depicting Jones in a prison chain gang, Robeson, bare-chested and shackled, “busts” rocks as he sings “Water Boy,” a plaintive song he performed in concerts.

Photographer Edward Steichen took twenty-six pictures of Robeson in his Emperor Jones costume, a military jacket with epaulettes, braid, and shiny brass buttons. In one of the images, Steichen captured a brooding, dark look on Robeson’s face—“defiance mixed with fear.” The iconic picture appeared in the August 1933 issue of Vanity Fair and led to movie offers from several Hollywood studios. Robeson turned them down. He felt that Hollywood wanted to portray only the “plantation type of Negro.” Robeson intended to do “human stories,” if only he could find one, but good roles for a black actor were difficult to find.

In his role as the Emperor Jones, Robeson glowers menacingly. This photo by Edward Steichen became an iconic image, exhibited in museums throughout the country.

The Emperor Jones movie was released in September at two New York theaters, the Rivoli, for white people, and the Roosevelt in Harlem for black audiences. It was a breakthrough. For the first time, a black actor played the lead in a full-length, mainstream “talking” picture. Critics applauded performances by Robeson and the cast, but members of the black community attacked the film for using the ‘n-word’. The Amsterdam News condemned Robeson for agreeing to perform in the movie. “O’Neill does not know Negroes,” stated the critic. “The Emperor Jones struck me…as being written for morons.” Robeson defended O’Neill’s script: “Coming from the pen of a white man it’s an almost incredible achievement, without a false note in the characterization.”

In January 1934, Robeson returned to concertizing, and he and Brown began a long tour through England. Aside from spirituals, Robeson sang Russian, Hebrew, Mexican, English, and Scottish folk songs. For him, the songs of these different lands shared a “common humanity,” in expressing the universal human emotions of delight, tenderness, protest, and the pain of suffering and loss.

When he returned home in April, Essie read a letter she had received from composer George Gershwin, who had written hit Broadway musicals as well as classical compositions. He had heard Robeson sing at parties. Gershwin was working on a folk opera, Porgy and Bess. “I have had Paul in mind for the part of Porgy,” he wrote, “which I think suits him admirably. I am bearing in mind Paul’s voice in writing it, and if there are some things which are out of his range, I am sure I can fix it up.” If Robeson had accepted the role, he would have broken the color barrier by being been the first black opera singer in America. But he declined Gershwin’s offer. He knew his voice wasn’t suited to operatic music, and he was determined to reach a broad popular audience, not just opera lovers.

Robeson kept looking for a movie project that would convey a true picture of African culture. That summer, director Zoltan Korda asked him to play an African chief, Bosambo, in an adventure movie, Sanders of the River. Korda had spent four months in Central Africa filming dances and rituals, and Robeson thought the footage was “magnificent.” Korda planned to use the footage throughout the movie. Robeson was especially excited about Korda’s recordings of African music. The music revealed “much more melody than I’ve ever heard come out of Africa,” said Robeson. “And I think the Americans will be amazed to find how many of their modern dance steps are relics of an African heritage.”

A still from the movie Sanders of the River, with Robeson in the starring role of Bosambo

Robeson took the part. But when he read the script, he realized that it presented a favorable view of British colonialism. In 1934, the United Kingdom still ruled many colonies throughout the world: India, Hong Kong, West Africa, South Africa, Jamaica, and the Bahamas. Although Robeson condemned the practice of European whites ruling people of color, he chose to do the film because it allowed him to portray an African character with a real African background.

The story takes place in British Nigeria, and centers on Bosambo, an educated tribal chief. Bosambo works with Sanders, a British river officer, to calm rebellious natives. But native warriors turn on Bosambo. Sanders rescues him and appoints him as the new king of the tribes. At the end, Bosambo, clad only in a leopard-skin loincloth and an ivory-tusk necklace, sings the “Canoe Song” as Sanders sails away. Robeson recorded the number, which became a popular hit.

Production began in the summer of 1934 at the Shepperton Studios, just outside London. Korda hired 400 black people, mostly Africans, as extras. Robeson enjoyed working with them and hearing their different languages. One day, he overheard a man speaking in his native language, and to his amazement, he understood what the man was saying. “I spoke to him at once,” recalled Robeson, “he was from the Ibo tribe in Nigeria—the very tribe and country from which my own father’s family came. Surely I must have heard a word or two of this language that had crept into my father’s speech and that he himself had inherited.” Robeson was thrilled. He told a reporter, “For the first time since I began acting, I feel that I’ve found my place in the world, that there’s something out of my own culture which I can express and perhaps help to preserve.”

During the weeks of filming, Robeson often took Paul Jr., age seven, to the set. “He taught me games of all kinds, told me stories, and stimulated my intellectual curiosity,” recalled Paul Jr. “I remember him as surprisingly playful for one who appeared on the surface to be so serious.” When they arrived at the studio, Paul Jr. observed his father’s “natural ease, making himself accessible to everyone. He was a popular superstar who belonged to the outside world, yet behaved like a regular person.”

But the final version of the film bitterly disappointed Robeson because it glorified British colonialism more than it had in the original script. During the last five days of shooting, an imperialist angle had been added without his knowledge or permission. He had expected to star in a serious film that presented the dignity of African culture. Instead, the movie was trite and corny.

At the premiere of the film at the Leicester Square Theatre, he was so angry he slipped out. According to one account, Essie went after him and persuaded him to return. When the screening ended, a piano was pushed onto the stage and he was asked to sing. Robeson refused in protest and later said, “I personally am sorry about doing Sanders,” and “I hate the picture.”

The reviews made him angrier. The London Sunday Times noted that Sanders provided “a grand insight into our special English difficulties in the governing of savage races.” Black people were portrayed as “childlike and superstitious.” When the black press criticized him for lending his name and prestige to a movie that patronized Africans, Essie defended him and said, “Look, we have to make money.”

However, Robeson took full responsibility for having made a mistake in trusting Korda and vowed never to work with him again. Robeson tried but failed to buy the rights to the movie and all the prints, to prevent distribution. The movie turned out to be a success at the box office, but Robeson donated his earnings: “All money earned from Sanders went to help Africa.”

Slowly, Robeson was becoming aware of the world around him and his ability to make changes. “It is not as imitation Europeans, but as Africans, that we have a value,” he wrote. “To remind the world that a Negro has something to offer, Paul Robeson will act and sing.”