chapter 22

scandalize my name

—“Scandalize My Name”

One of the few people unimpressed by Robeson’s triumph in Othello was J. Edgar Hoover. After receiving reports from his agents about Robeson’s speeches at political events, and his recording of the new Soviet National Anthem, Hoover believed that Robeson was “undoubtedly 100% Communist.” Hoover recommended that Robeson be considered for immediate arrest in the event of a national emergency. On April 30, 1943, a card marked “custodial detention” was issued for Robeson. By August, he was labeled “a leading figure in the Communist party…actively attempting to influence the Negroes of America to Communism.”

Robeson seemed unaware of the FBI’s surveillance and continued to speak out for his favorite causes: obtaining equal rights for African Americans, winning freedom for people under colonial rule, helping the workers’ unions, and promoting support for the Soviet Union. Hoover branded these causes as “activities in behalf of the Communist Party.” FBI agents trailed Robeson and illegally tapped his phone conversations. The more Robeson expressed his views, the more Hoover devoted personal attention to his file. To the FBI, Robeson was classified as a dangerous subversive in the category of a spy.

Robeson gave Hoover ample opportunity to malign him. On December 3, 1943, he spoke at a meeting with the owners of major league baseball teams to discuss black players being barred from playing professional baseball. “I come here as an American and former athlete.” Then he cited his own experiences in college football, which had never resulted in a racial disturbance. “The time has come that you must change your attitude toward Negroes,” he said. When Robeson finished speaking, the club owners applauded. Although nothing changed that season, they had listened and unanimously agreed to remove barriers preventing the signing of black baseball players.

On April 16, 1944, the Council on African Affairs (CAA) sponsored a huge celebration for Robeson’s forty-sixth birthday. Robeson had cofounded the CAA in London back in the 1930s. It was a left-wing group dedicated to winning freedom for colonies in Africa and independence for India. Robeson had continued to support the CAA and was the chairman. It was the first organization that connected the struggle of African Americans for civil rights and the fight of colonized people in Africa and Asia for freedom. Eight thousand people gathered at New York City’s Armory for the event, and thousands were turned away. Mary McLeod Bethune, a black civil rights activist and educator, hailed Robeson as “the tallest tree in our forest.” As Robeson responded to the tributes, he choked up and grew teary. “Save your voice, Paul!” yelled someone in the audience. The crowd joined an all-black soldiers’ chorus, singing “Happy Birthday, Dear Paul.” Army intelligence agents were also at the Armory that day and shared a detailed report with the FBI.

Agents began to follow Essie, too, a political and social activist in her own right. On June 10, 1944, Hoover sent a letter to the special agent in New Haven. He wrote that a “security index card has been prepared at the Bureau.” The card labeled Essie a communist. Like Paul, she belonged to the CAA, and she participated in various public programs. Recently, she had attended an interracial meeting of influential women in Georgia. The state’s segregationist laws made the meeting illegal, but Essie and the other women still dared to gather. Essie also published her book, African Journey, which established her as an expert on Africa and a recognized lecturer.

Without realizing that he and Essie were at risk, Robeson carried on with his political and theatrical life. Othello closed in July 1944, after 296 performances. The show set a Broadway record for a Shakespearean production. In September, the cast began a nine-month coast-to-coast tour of the United States and Canada.

On the tour, Robeson insisted that they perform only in theaters that were not segregated, setting an important precedent. Their last stop was Chicago. During the run, news came that President Franklin D. Roosevelt had died suddenly on April 12, 1945. That night, the cast dedicated their performance to the president’s memory. At the curtain call, Robeson praised the president as a person who had believed that the “rights of man [were] more important than the rights of private property.” Robeson predicted that Roosevelt’s death would change things, and not for the better.

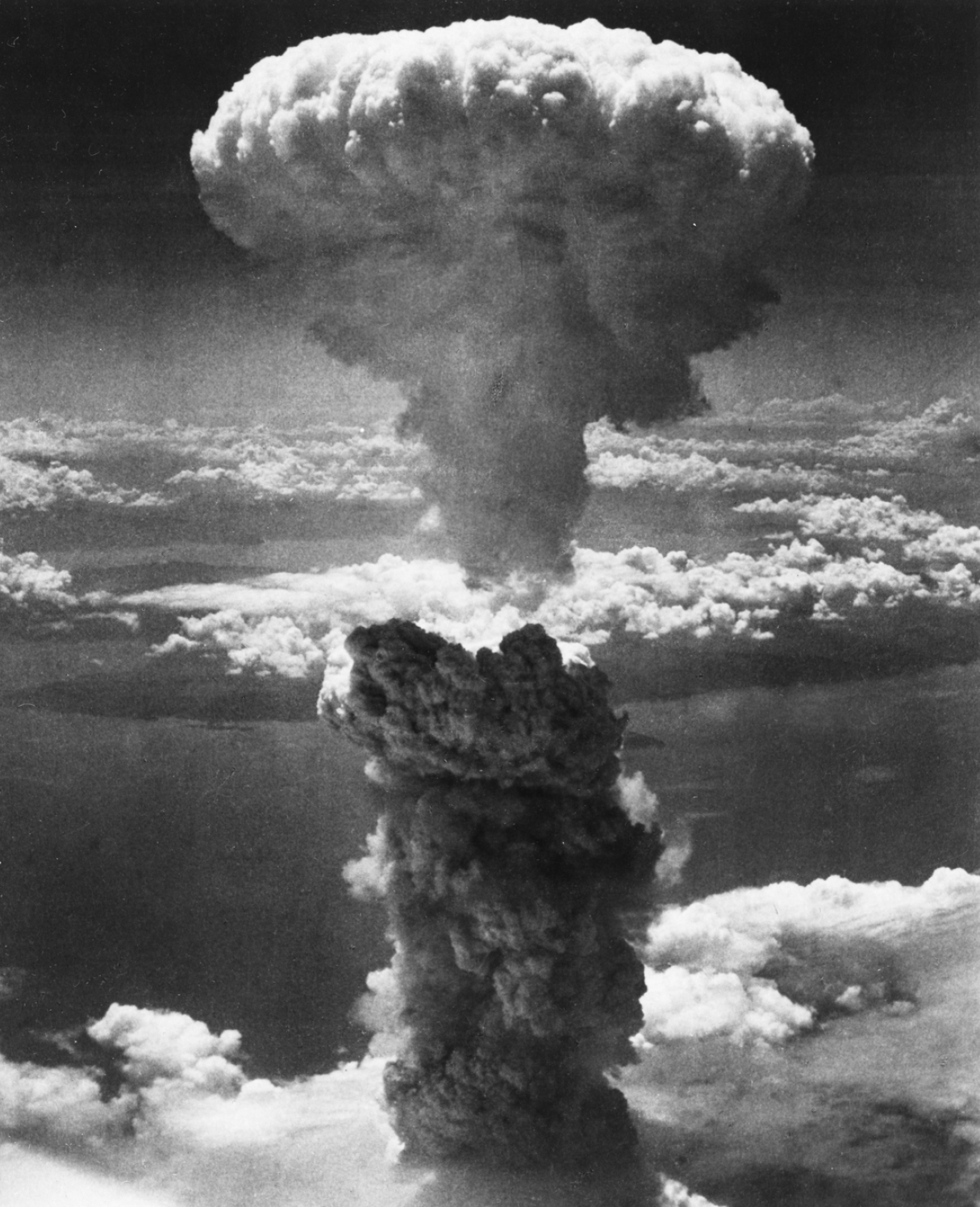

On May 8, 1945, V-E Day, the Germans surrendered to the Allies, ending the war in Europe. But Japanese military leaders refused to surrender unconditionally. Roosevelt’s successor, President Harry S. Truman, decided to use the atomic bomb against Japan. On August 6, American pilots dropped the bomb on the city of Hiroshima. Hundreds of thousands of people were killed, mostly civilians. Houses were obliterated. Still, the Japanese generals would not back down. On August 9, a second atomic bomb was dropped on the city of Nagasaki. Finally, on August 15, the Japanese surrendered. World War II was over.

That month, Robeson and Brown traveled overseas on a concert tour sponsored by the USO. They were accompanied by white musicians, forming the first interracial unit sent to entertain the troops. During the month-long tour, they gave thirty-two performances, including a concert at Hitler’s opera house in Nuremberg, Germany. At a German army base, Robeson spoke with soldiers who had liberated the concentration camps. He listened intently as they described the shocking horrors they had seen—thousands of unburied dead bodies, walking skeletons too sick and starved to survive being free. Robeson’s appearances “inspired black soldiers throughout Europe and gave a badly needed boost to their morale,” wrote Paul Jr. A white serviceman in Germany described his experience when he heard Robeson sing the revised closing lines of “Ol’ Man River”:

Nagasaki, Japan, under atomic bomb attack by the U.S. Army on August 9, 1945. The bomb known as “Fat Man” killed between 40,000 and 75,000 people immediately, while 60,000 others suffered severe injuries.

Robeson talks to African American soldiers during his concert tour to entertain the troops in France, Czechoslovakia (now the Czech Republic), and Germany, August 1945.

I’se so weary and almost dyin’

But I keeps laffin’ and keeps on tryin’.

“As he sang those words, his face lit up in a ferocious fighting grin, and he pounded his fist in his hand and sang directly at the group of colored boys in the audience,” wrote the serviceman. “And you can bet that I was saying with every atom of me, ‘More and more power to you.’ ”

Back home, Robeson received the NAACP’s Springarn Medal, the most prestigious award in the black community. The medal is given annually “to the man or woman of African descent and American citizenship, who shall have made the highest achievement during the preceding year or years in any honorable field of human endeavor.”

Upon receiving the award at the banquet, Robeson stunned the audience with his speech, which criticized America for resisting civil rights reform. He pointed out that black soldiers returning to America no longer wanted to be treated like second-class citizens. After proudly serving their country, they expected changes at home but instead encountered an outbreak of racial violence aimed at “uppity” black veterans. He cited Mississippi, where racism was especially strong, and black veterans were prevented from registering to vote by literacy tests, property tax receipts, and terrorist threats. White supremacists, he noted, enforced these unjust obstacles so that black citizens couldn’t exercise their political rights. And they weren’t about to stop.

Robeson also attacked the government for showing renewed signs of hostility toward Russia. “Full employment in Russia is a fact, and not a myth,” he said, “and discrimination is non-existent.” Lastly, he lashed out against America’s support of colonialism, and emphasized India’s continued struggle for independence. FBI agents reported his every word.

In September, Robeson and Brown left on the longest concert tour they had ever made, which continued into the spring of 1946. Along the way, Robeson was appalled by the wretched housing conditions and poor job opportunities he witnessed in the black community. He heard reports of police brutality and an increase in the number of lynchings. Brown said that Robeson was in a “foul mood” for most of the tour and “more difficult to work with than during all the years before…. He constantly felt he could not sing another concert.” Yet Robeson was at the peak of his power as a singer and still a great favorite with audiences.

More and more, Robeson concerned himself with the horrific attacks on black Americans. Between June 1945 and September 1946, fifty-six black people were brutally lynched. In South Carolina, Sergeant Isaac, Woodard Jr., a decorated African American veteran who had served in the South Pacific for fifteen months, was falsely arrested and then blinded in a vicious beating by a white police chief who was later tried and acquitted. The NAACP had tried without success to convince President Roosevelt to support a federal anti-lynching bill. On September 12, Robeson spoke with indignation at a rally at Madison Square Garden. “Stop the lynchers!” he cried. “What about it, President Truman? Why have you failed to speak out against this evil?”

Robeson and black leader W. E. B. Du Bois planned a conference in Washington, DC, to launch “an American crusade against lynching.” Albert Einstein agreed to cochair the project. The conference took place on September 23, with 1,500 black and white attendees, representing various organizations.

Robeson headed a delegation that went to the Oval Office to meet President Truman. But when the president was asked to issue a public statement denouncing lynching, he said the time wasn’t right for him to speak out. Robeson pointed out that in Nuremberg, Germany, prosecutors from the Allied nations were presenting cases against Nazis accused of war crimes against humanity. He said it seemed “inept” for the United States government to take the lead in prosecuting Nazis while failing to “give justice to Negroes in this country.” Robeson warned that the mood of black people was changing. He told Truman that if the federal government refused to defend them against murder, blacks would have to defend themselves. Truman angrily shook his fist at Robeson and said that sounded like “a threat.” Robeson assured him it was not a threat but rather a statement of fact. Truman abruptly ended the meeting.

Later that day, Robeson stood in front of the Lincoln Memorial and gave a radio address. “People of America,” he said, “we appeal to you to help wipe out this inhuman bestiality, this Ku Klux Klan hooded violence.” He said he felt ashamed that so many years after President Abraham Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation freeing enslaved people, in 1863, it was still necessary to speak “of the lynch terror and mob assaults against Negro Americans.”

Robeson marches at a civil rights protest in Washington, DC, 1948.

Two weeks later, Robeson was called to testify before the Joint Fact-Finding Committee on Un-American Activities in California. The committee was formed to investigate people deemed subversive. The chairman began by asking Robeson about his trips to the Soviet Union. He asked if Robeson’s son had been educated in the Soviet Union, and if he was a citizen of the Soviet Union. “He is not,” replied Robeson. “He was born in the United States.”

Then the chairman asked Robeson if he was a member of the Communist Party and added, “I ask it of everybody, so don’t feel embarrassed.” Robeson said, “No. I am not embarrassed…. Every reporter has asked me that…. Only you might ask me if I am a member of the Republican or Democratic Party. As far as I know, the Communist Party is a very legal one in the United States…. If I wanted to join any party, I could just as conceivably join the Communist Party, more so today than I could join the Republican or Democratic Party. But I am not a Communist.”