Inaccuracy of many care labels, low labeling … FTC regulations; how to interpret care labels … What the care label means when it is silent, when it gives warnings, when it does not mention ironing, when it prescribes no bleach or non-chlorine bleach; what care labels do not have to tell you … When to disregard care labels and when not to … What to do when the care label procedure causes damage … Glossary of Care Label Terms and Symbols … Appendix, Extracts from FTC Regulations on Care Labels

Following Dr. Seuss’s example, I feel obliged to warn the reader that this chapter is dangerous. It contains advice on when and why you might wish to disobey that fundamental law of the modern laundry: “Follow the instructions on the care label!” “Those of you who are beginners should follow the care labels unless it is clear you have nothing to lose—for example, when the garment looks so awful that you are never going to wear it again in its present state anyway and there is no way to remedy it if you limit yourself to care label instructions. Even then, you have to think of your chagrin when someday you find out that you could have saved it by trying another remedy that you had not known about. If this sounds too frustrating, follow that care label, or hand the problem over to a professional. Otherwise you risk the destruction of your fabrics, their colors, or their appearance. I have given garments to my dry cleaner saying, “Try anything. It’s ruined as it is, so I won’t blame you if you make it even worse.”

Those of you who are not beginners should also be prepared to accept the risks, because in this area no one can offer you certainty, least of all someone who has never even seen the fabric or problem you are dealing with. First survey the risks (including the possibility that you might render a wearable garment unwearable) and decide if you can accept failure. Remember, if it is a T-shirt, this means merely a little money and some inconvenience; if it is an expensive cashmere sweater, this could leave you with quite a hole in your pocket and nothing to wear this weekend.

The Uses and Limits of Care Labels

All wearing apparel (except footwear, gloves, hats, and other head and hand coverings) and piece goods used for home sewing of apparel sold in this country, including imported clothes and piece goods, are subject to the care labeling rules promulgated by the Federal Trade Commission. These rules require the manufacturer to attach a permanent label to each garment telling the buyer how to clean it. The regulations mandate that the label tell you at least one form of regular care, either washing or dry cleaning, needed for the ordinary use and enjoyment of the product, and that it warn the buyer against procedures that the buyer might assume are safe if in fact they would result in damage to the product or others being laundered with it.* The instructions on the label must cover trim, lining, buttons, and any other permanent part of the garment.

Surveys show that most home launderers pay attention to instructions on care labels, and textile and laundering experts unanimously advise you to follow care labels. If you do not, you run the risk of ruining your chances of a refund or replacement, for if you follow improper laundering procedures, any damage is likely to be considered your own fault. This seems fair enough until you look at some of the practicalities.

Every home launderer will have had plenty of experiences like my own with care labels. Among my son’s new school clothes one year, for example, were two 100 percent cotton knit shirts, one in green and one in red, made by different manufacturers and bought at different stores. I would have bought neither of them if I had bothered to read the care labels, which specify treatment that is not the most practical for the clothes of the active son of busy parents: “Wash separately, cool water. Dry flat.” One of the shirts bled dye at every washing, even in cool water; it faded quickly and accumulated some oily stains that were impossible to get out with cool water. The other shirt never bled dye at all, not even in hot water, never faded, and shrank just enough to fit perfectly, even after repeated tumble drying on low heat. Its care label instructions were flat wrong, but there was no way to determine this without bringing it home and experimenting; it looked just like the other shirt, which really did require separate washing.

For another example, I have an oversized, white cotton T-shirt that I bought in 1986 whose care label says, “Machine-wash warm. No bleach.” I have machine-washed it in hot water hundreds of times, usually with chlorine bleach. It has hardly shrunk at all, and although it became comfortably soft and thin after more than a decade of good wear, it still looked white and attractive, and only developed holes when it turned eighteen. Overcautious labels when it comes to bleaching appear to me to be more the rule than the exception. But the problem is the opposite when it comes to ironing. My family’s closets are full of shirts that lack any care label instruction as to ironing and nonetheless require regular ironing to look presentable.

Then there are those irksome care labels on ordinary sheets and towels that counsel utterly irrational caution. Towels, for example, which have been available for decades with profound colorfastness (colorfastness to withstand even chlorine bleach), now frequently have labels that advise you to wash them separately, wash them cold, and—hard to believe—to tumble dry on low. Of course, everyone will ignore this, because towels would take forever to dry on low. And, I hope, everyone will leave in the store looking decorative all those bath towels that require cold or separate washing or have any places or parts that shrink in a hot dryer. For everyday use, hold out for towels that can work hard, receive stain treatments and laundering that sanitizes (when necessary), and cause you no trouble. There is no reason in the world why toweling cannot be beautiful and practical too. But, of course, if buyers do not hold manufacturers to reasonable standards, manufacturers will certainly not hold themselves to any.

As an experiment, you might try (as I once did) sorting your laundry according to the exact instructions on the care labels. Because practically no two articles are labeled identically, even if, in quantity, you have only clothes enough to make up three or four good-sized loads, you might end up sorting them into at least three times that many loads. No experienced home launderer actually washes twelve or more loads instead of three or four. Thus we all become care label skeptics, routinely defying their instructions.

Inaccurate labeling and “low labeling” (labels that prescribe more conservative care than the garment really needs) are both quite common. Nonetheless, some of our skepticism about labels is in fact mistaken. We might fail to recognize that a label is accurate if, for example, a garment labeled “Dry-clean only” seems perfectly all right after being laundered. The effects of laundering may become apparent only after the third or fourth wash, and those effects may include shrinkage, fading, weakening, or the loss of beneficial treatments and finishes. By the time you discover that the label was right all along, it is too late to save the garment.

In other cases, a garment’s care label simply cannot give the whole picture. Knowledgeable readers will appreciate, given how complicated a fabric’s cleaning story can be, that manufacturers should not be faulted for not getting all the nuances on a square inch or two of care label. Moreover, what constitutes the “best” treatment will in some respects turn on the goals and skills of the person who will apply it: Is longer wear or whiter appearance more important? Is expense any object? Is the buyer a skilled and willing ironer?

A care label is intended to help you launder safely and effectively by giving you some simple guidelines. Care labels are not intended to do away with your need to know, more or less, what you are doing when you putter around in the laundry. I have often wondered whether we would be better off if we had regulations that required manufacturers to inform us about the characteristics of the products instead of the rather authoritarian care label system that asks us to obey simpleminded instructions blindly without giving us any hint of the reasons behind them. But because there is no likelihood that the system will change anytime soon, you are often going to find yourself wanting and needing to use laundry procedures other than the ones that are recommended on the labels.

There are three main reasons for sometimes ignoring care labels. The first is that you want to do a better job than you believe is possible with the recommended treatment. The second is that you believe you can safely and effectively clean the garment with less trouble or expense than the care label treatment would require. The third is that you want to wash in one load clothes whose care labels would require different treatment. Before you can decide to ignore a label you need to be able to make educated guesses about whether an alternative procedure is safe. This requires being able to spot potential problems and decide when the risk is worth it. You must also be prepared to accept the loss when you guess wrong. I repeat: If you are a novice, just follow the care labels. The less you know, the greater the risks of doing anything else. Sooner or later, however, every novice develops an instinct for fibers, fabrics, and laundering, and discovers for himself or herself when the risks are small enough to justify taking a chance.

The FTC Regulations: What Care Labels Do and Do Not Tell You

The glossary at the end of this chapter sets forth definitions of certain standard terms and symbols that are permitted on permanent care labels. If you do not know the meaning of the terms or symbols on your clothes’ care labels, consult the glossary (see page 34). Better yet, photocopy it and tape it to the wall or put it on a bulletin board in your laundry. Although the discussion that follows often talks about what care labels “say,” the labels may use symbols, words, or both so long as the instruction is consistent with FTC rules. The heart of these rules, the provisions governing washing and dry cleaning instructions, are set out in the appendix at the end of this chapter, pages 36-37, following the glossary.

ITCHY LABELS

Sometimes labels are made of stiff, scratchy material that irritates the skin—especially children’s sensitive skin. If you cut the care label off and you think you need it as a reminder, pin it to a bulletin board in your laundry with a note saying, for example, “Manufacturer X’s striped T-shirt.” Better, but more trouble, is to reattach it to the garment, with firm stitching, someplace where it is less irritating, say at a side seam within a couple of inches of the bottom hem. Some manufacturers have begun to print the care instructions directly on the fabric of the garment. In my experience, this method is long-lasting and convenient as well as more comfortable.

The Meaning of Silence. Most care label instructions you will encounter are straightforward, but some have implications that are not so obvious. Often, it is what the care labels do not say that creates confusion. For example, when both dry cleaning and washing are safe for regular use on a product, the rules do not presently require the manufacturer to say so on the care label. Rather, under the rules as they now stand, “the label need have only one of these instructions.” Thus, a label that says merely “Dry-clean” means neither that you can nor cannot wash the article without harming it. (“Dry clean only” does mean that washing will harm it.) And if the label says “Machine-wash,” you have been told nothing about whether it can also be dry-cleaned or whether dry cleaning would harm it. The manufacturer is required neither to recommend an alternative method if it would be safe nor to warn you if it would not be safe. Despite requests by consumers, consumer interest groups, laundry product manufacturers, and the EPA, in 2000 the FTC refused to amend its rules to require washing instructions on all articles that could safely be washed.*

Sometimes, however, silence on a care label means that, in some respect or other, anything goes. For example, a label that says nothing about washing, drying, or ironing temperatures means that any temperature is safe. A label that says nothing about bleach means that all household bleaches are safe and can be used regularly. “Machine-wash, tumble dry” means that any temperatures for washing and drying and all types of household bleach may be used.

Warnings. The words “only,” “do not,” and “no” are always warning words on care labels. Warnings mean that harm is likely to ensue, in one or more washings, if the instructions are not followed. For example, if a label says “Dry-clean only,” the word “only” makes this a warning against machine washing; and the instruction means that machine washing will be harmful. If the label says “Wash with like colors” or “Wash separately,” despite the absence of obvious warning words, you are being warned that the article is not colorfast and may bleed dyes onto anything washed with it. There is also an implicit warning against a stronger alternative when a care label specifies a gentler one; for example, a label that prescribes warm water is implicitly warning you not to use hot, even though no explicit warning words are used. Note, however, that the FTC rules require the manufacturer to warn you only about harmful aspects of the recommended treatment. A label that says “Machine-wash” need not tell you whether or not dry cleaning will harm the garment, but it must tell you if bleaching would.

Ironing. If a label says nothing at all about ironing, that is supposed to mean that no ironing is needed to “preserve the appearance” of the garment. But this provision of the rules, so far as I can tell, is routinely ignored; many garments that require ironing have care labels that do not mention ironing. Presumably, manufacturers think that telling people they have to iron would not be a big selling point.

Bleaching. If a label says “No bleach,” this does not mean that the article will stay white or bright without bleach, or that bleach is unnecessary. Some garments that are marked “No bleach” do not stay white without bleach. You may infer only that the manufacturer is telling you that all types of household bleach can reasonably be expected to harm the product in one or more washings.

If regular use of chlorine bleach would harm the product but regular use of a non-chlorine bleach would not, the label must say “Only non-chlorine bleach, when needed.” This instruction seems to tell you that you are to use a non-chlorine (or oxygen) bleach only when the product starts to look dingy, but—whatever the instruction is really intended to mean—in practice this would often be a mistake. In general, non-chlorine bleach is effective only when used regularly to prevent a dingy appearance from developing and can do little to remove it when it has already developed. Nonetheless, the manufacturer, it seems, has no lawful choice but to give you this exact wording, misleading as it may be, if it wants to warn you against using chlorine bleaches but not against other types of bleach. This required wording is misleading in another way, too: it does not allow for cases in which “irregular” or occasional use of chlorine bleach might do no harm.

What Care Labels Do Not Have to Tell You. You should not assume, when you read a care label, that the manufacturer is trying to give you the least expensive or the best or even both of two equally good sets of care instructions. The rules do not require this, and care labels very often do not do so.

When care labels give warnings, they are not required to explain what danger is being warned against, how big a danger it is, or how likely the danger is. Care labels never tell you why one procedure is recommended rather than another, whether it is because a garment might fade, shrink, pill, or go limp or shapeless, whether invisible finishes may dissolve, and so on. Care labels do not tell you whether the product has received wrinkle-resistance or other treatments or whether any instructions on the label are there to protect a finish. Manufacturers are not required to tell you on care labels how much shrinking you can expect, nor when instructions are geared toward preventing shrinkage.

Care labels are not required to tell you when starch or sizing is necessary to restore the crisp appearance of a garment, or when ironing should be done when the clothes are damp. Apparently, they are also not required to give instructions on the use of soaps or detergents, softeners, bluing agents, boosters, and the like, and they rarely do, except, occasionally, to advise the use of mild soap or detergent.

At the present time, care labels are not required on gloves, hats, handkerchiefs, neckties, shoes, and similar items of attire, or on sheets, mattress pads, tablecloths, blankets, towels, rugs, upholstery, and many other textile products used in the home. Wisely, manufacturers almost always include care labels on towels, linens, and other textile goods even though they are not required. When care labels are absent, as sometimes happens on imported towels and linens, you have to rely entirely on labels describing fiber content—which are, fortunately, required by the Textile Fiber Products Identification Act for all domestic and imported textiles—and use care procedures appropriate to the fibers. (See Part III.)

Disregarding Care Labels Carefully

Those who wish to at times defy care labels will find that their best protection from frustrating laundry errors is understanding fabrics and fibers. (See Part III, chapters 19, 20, 21, and 22, for general information about fabrics and the care procedures appropriate to fabrics made of different types of fibers.) If you wish to launder or clean in a way other than the one recommended on a care label, you should be aware of the general nature of the fiber and construction you are dealing with and what is generally safe and effective in laundering such a fiber and construction, even though particular articles may have to be treated differently. To try to figure out whether the garment is actually launderable or cleanable in the way you intend, you should look for hints on the care label, on hang tags, and on fiber content labels, and you should examine all parts of the garment—its trim, linings, interfacings, buttons, and so on. Consider the weave and the yarn construction. Before proceeding, test for colorfastness, yellowing, and the like. Ask sales personnel whether they have any experience with the type of garment in question. Manufacturers may recommend a given procedure for a variety of reasons that you can only guess at.

Here are some specific ways in which it often pays to depart from care label instructions. Following these guidelines, you may sometimes ruin something, but in the long run your laundering is more effective and more efficient.

You can also depart from care label instructions in the direction of being more cautious rather than less so. The usual reason to do this is to combine a stray item or two with a larger load, by giving it a less rigorous treatment than it could safely take. For example, you can

The potential cost of using milder or gentler or cooler treatments is that clothes may not come as clean or may take longer to dry. Over time, dirt retained in the fibers weakens them and makes clothes appear gray and dingy or even feel unpleasant. However, the effects of retained dirt are not going to show up if you occasionally or infrequently make this compromise, for the sake of fewer loads. You would probably never wish to wash heavily soiled children’s play clothes in cold water with mild detergent, for they simply will not come clean. But play clothes with moderate soil that you usually give strong treatment to would probably do fine if they were occasionally washed in warm water with permanent-press clothes on the permanent-press cycle—especially if you have pretreated any stains or heavy soil marks.

When Not to Disregard Care Labels

If you are in the habit of ignoring care labels, you will minimize your risks if you know that some care label instructions should never or rarely be disregarded. Here are a number of situations in which you should obey care labels:

For General Reasons

For Reasons Related to Construction of Garment, Fabric, or Yarn

For Reasons Relating to Fiber Content

For Reasons Relating to Dyes and Finishes

When Instructions Relate to Bleaching

When Instructions Relate to Ironing and Drying

What to Do When the Procedure Recommended by the Care Label Causes Damage

If an article is damaged when you launder or clean it in accordance with the care instructions, the FTC recommends that you return the article to the retailer who sold it to you. The FTC suggests that if the retailer refuses to “resolve the problem,” ask for the name and address of the manufacturers and write them a letter. “In your letter, fully describe the garment and give all the information that is on the labels and tags,” advises the FTC. “Estimate how many times the garment has been washed or dry-cleaned and give the full name and address of the store where you bought it.” You can also get in touch with the FTC, and you should definitely do so if the manufacturer fails to give you a satisfactory resolution. Write to Correspondence Branch, Federal Trade Commission, Washington, DC 20580; or call 202-326-3693. The FTC will not attempt to resolve your grievance, but the information you provide it “may reveal a pattern or practice requiring action by the Commission. You may be contacted if the FTC decides to investigate.”

In my experience, however, retailers and manufacturers are almost always happy to make an exchange or refund.

Machine-wash. Use washing machine, hot, warm, or cold setting. See the note on page 27 of this chapter for the temperature ranges meant by “hot,” “warm,” and “cold.”

Machine-wash, warm. Use washing machine, warm setting. (Hot water should not be used.)

Machine-wash, cold. Use washing machine, cold setting. (Hot or warm water should not be used.) (Note that the absence of any instruction concerning bleaches or ironing should be interpreted as meaning that all commercially available bleaches may be used on a regular basis without harm, and that no ironing is necessary to preserve the appearance of the garment.)

Hand-wash, cold. Wash by hand in cold water. (Machine-washing and warm or hot water should not be used.) Only non-chlorine bleach. Non-chlorine bleach can safely be used when needed. (Regular use of chlorine bleach would harm the product.)

No bleach. [Do not bleach.] Use no bleach. (All commercially available bleaches would harm the product when used on a regular basis.)

Tumble dry. High, medium, or low dryer temperature setting can safely be used.

Tumble dry, medium. Medium or low dryer temperature settings can safely be used. (The hot setting should not be used.)

Tumble dry, low. Low dryer temperature settings can safely be used. (The hot and warm settings should not be used.)

Iron. High, medium, or low iron settings can safely be used.

Warm iron. Iron on a medium temperature setting. (The hot setting should not be used.)

Cool iron. Iron on the lowest temperature setting. (The hot and warm settings should not be used.)

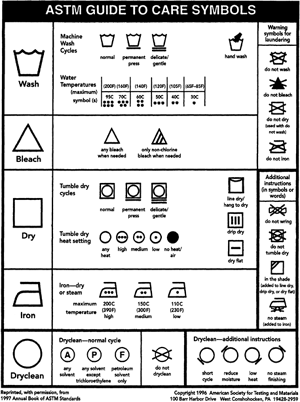

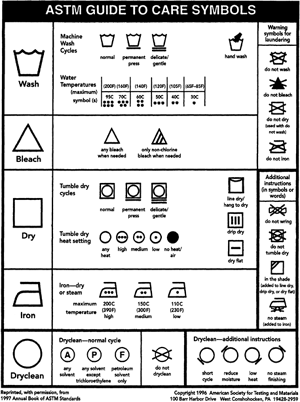

This figure illustrates the symbols used for laundering and dry cleaning instructions. As a minimum, laundering instructions should include, in order, four symbols: washing, bleaching, drying, and ironing; and drycleaning instructions should include one symbol. Additional symbols or words may be used to clarify the instructions.

Extracts from FTC Regulations on Care Labels

(1) Washing, drying, ironing, bleaching, and warning instructions must follow these requirements:

(i) Washing. The label must state whether the product should be washed by hand or machine. The label must also state a water temperature—in terms such as warm, cold, or hot—that may be used. However, if the regular use of hot water up to 145°F (63°C) will not harm the product, the label need not mention any water temperature. [For example, “Machine wash” means hot, warm, or cold water can be used.]

(ii) Drying. The label must state whether the product should be dried by machine or by some other method. If machine drying is called for, the label must also state a drying temperature that may be used. However, if the regular use of a high temperature will not harm the product, the label need not mention any drying temperature. [For example, “Tumble dry” means that a high, medium, or low temperature can be used.]

(iii) Ironing. Ironing must be mentioned on a label only if it will be needed on a regular basis to preserve the appearance of the product, or if it is required under paragraph (b) (1) (v) of this section, Warnings. If ironing is mentioned, the label must also state an ironing temperature that may be used. However, if the regular use of a hot iron will not harm the product, the label need not mention any ironing temperature.

(iv) Bleaching.

(A) If all commercially available bleaches can safely be used on a regular basis, the label need not mention bleaching.

(B) If all commercially available bleaches would harm the product when used on a regular basis, the label must say “No bleach” or “Do not bleach.”

(C) If regular use of chlorine bleach would harm the product, but regular use of a non-chlorine bleach would not, the label must say “Only non-chlorine bleach, when needed.”

(v) Warnings.

(A) If there is any part of the prescribed washing procedure which consumers can reasonably be expected to use that would harm the product or others being washed with it in one or more washings, the label must contain a warning to this effect. The warning must use [the] words “Do not,” “No,” “Only,” or some other clear wording. [For example, if a shirt is not colorfast, its label should state “Wash with like colors” or “Wash separately.” If a pair of pants will be harmed by ironing, its label should state “Do not iron.”]

(B) Warnings are not necessary for any procedure that is an alternative to the procedure prescribed on the label. [For example, if an instruction states “Dry flat,” it is not necessary to give the warning “Do not tumble dry.”]

(2) Dry-cleaning.

(i) General. If a dry-cleaning instruction is included on the label, it must also state at least one type of solvent that may be used. However, if all commercially available types of solvent can be used, the label need not mention any types of solvent. The terms “Drycleanable” or “Commercially Dry-clean” may not be used in an instruction. [For example, if dry cleaning in perchlorethylene would harm a coat, the label might say “Professionally dryclean: Fluorocarbon or petroleum.”]

(ii) Warnings.

(A) If there is any part of the dry-cleaning procedure which consumers or drycleaners can reasonably be expected to use that would harm the product or others being cleaned with it, the label must contain a warning to this effect. The warning must use the words “Do not,” “No,” “Only,” or some other clear wording. [For example, the dry-cleaning process normally includes moisture addition to solvent up to 75 percent relative humidity, hot tumble-drying up to 160°F, and restoration by steam press or steam-air finish. If a product can be dry-cleaned in all solvents but steam should not be used, its label should state “Professionally dry-clean. No steam.”]

(B) Warnings are not necessary to any procedure which is an alternative to the procedure prescribed on the label. [For example, if an instruction states “Professionally dry-clean, Fluorocarbon,” it is not necessary to give the warning “Do not use perchlorethylene.”]

* In a few instances, the care instructions may appear on a hang tag or package rather than being permanently affixed to the garment. This is true of reversible clothes whose appearance might be ruined by a visible label. It is also true of garments that can be cleaned by any normal methods without harm. In the latter case, the hang tag must show this statement: “Wash or dry-clean, any normal method.” This means that you may wash and dry at hot temperatures, use all types of bleaches, including chlorine bleaches, and dry-clean with any ordinary solvents. If a product cannot be cleaned by any method, the manufacturer is required to attach a label saying so, for example, “Do not wash, do not dry-clean” or “Cannot be successfully cleaned.”

* In 2000, the FTC also decided not to amend the rule “at this time” to include an instruction for professional wet cleaning on garments that carry a drycleaning instruction. (Wet cleaning is an environmentally favorable cleaning technology that uses water instead of drycleaning solvents and is safe for a wider variety of fabrics than normal laundering.) And it revised water temperature definitions to make “hot” mean 112°F to 145°F (45°C to 63°C), “warm” mean 78°F to 111°F (31°C to 44°C), and “cold” mean up to 86°F (30°C). Prior to this amendment, “hot” meant water up to 150°F (66°C), “warm” meant 90°F to 110°F (32°C to 43°C), and “cold” meant water up to 85°F (29°C). See chapter 4, “Laundering,” pages 65-67.