Using the automatic dryer … What goes in the dryer … Load size, temperature, moisture sensing, cycle choices, avoiding overdrying, sorting for drying, operating the dryer … Using the dryer to unwrinkle … Line-drying … How to hang things on the line … Hanging dry on hangers or hanging racks … Drying flat

Most people today have no choice but to dry laundry indoors in an automatic tumbling dryer or on a hanger, a rack, or an indoor Une. These are all fine methods, and among them they provide the best means of drying some kinds of fabric. For those who have the option, however, outdoor line-drying gives the freshest result and would be my preference for all those clothes and linens for which it is suitable. This chapter canvasses how and when to use each of these options.

The Automatic Dryer

What Goes in the Dryer. Most clothes and linens can safely be dried in the automatic dryer. The exceptions are fiberglass, rubber, and plastic; certain especially heat-sensitive fabrics, such as olefin (polypropylene); many acetate, acrylic, and spandex fabrics; certain knits; drip-dry clothes; and many delicate fibers and fabrics, including viscose rayon. Drip-dry clothes should be hung to dry. Towels, flannels, and other pile and napped fabrics, on the other hand, need tumbling in the dryer to fluff them up. Ordinarily, they should not be dried flat or hung to dry. Superwash and similar treated wools may be tumbled in the dryer on a low setting (unless the care label says not to), but other wools must be dried outside the dryer. Once wool articles have dried outside the dryer, however, they can then be fluffed up on a setting that uses no heat, often called “air fluff.”

Load Size. A washing load is usually about the same size as a drying load. Drying loads, like washing loads, should be neither too small nor too large. A dryer with a full, wet load looks two-thirds empty. Remember that clothes will fluff up and take more space when they are dry. Too small a load will dry more slowly, as the tumbling action requires a minimum fill level to work properly. If a load is too small, add a few clean, dry items—say, two or three non-linting towels of compatible color—to bulk it up. Too large a load will wrinkle, lint excessively, and dry slowly and unevenly because air will not be able to circulate freely around the clothes. An overlarge load can also block the vent and cause heat damage to clothes.

A properly loaded clothes dryer

Temperature. Home dryers always give a choice of temperatures. Regular, or the hottest temperature, is for sturdy cottons—T-shirts, towels, cotton underwear, sheets, preshrunk blue jeans, and so on. Care labels on articles that may be dried on regular should simply say “Tumble dry.” In general, the hotter the drying temperature, the greater the likelihood of shrinking, so this setting is also reserved for preshrunk or low-shrink fabrics. The medium setting is for permanent-press, wrinkle-treated clothes, many synthetics and blends, lightweight cottons and linens, some knits, and those whose care labels direct “Tumble dry medium.” The low or delicate settings are for more heat-sensitive garments, including some synthetics, fine lingerie, sheer fabrics, and most cotton knits, as well as for those whose care labels direct “Tumble dry low.”

Moisture Sensing and Timed Drying. All dryers let you set drying time with a timer. Many home dryers now also offer “electronic drying,” in which the machine automatically senses the moisture level and turns off when it is reduced to the level you select, from “more” or “very” dry, to “less” dry. The “very dry” setting is for items you wish to get extra dry as well as hard-to-dry items like rugs, very heavy clothes, and towels. The less dry setting should be used for cottons and linens that you are going to damp-iron, although I find that they still need steam ironing or sprinkling. (See “Avoiding Overdrying; Damp Drying,” below.) Everything else takes the medium or “normal dry” setting.

Cycle Choices. Many home dryers also offer a choice of cycles: regular, permanent-press, and air fluff. The regular cycle has a short cool-down period at the end for less wrinkling and easier handling when you remove the clothes. The permanent-press cycle has a long cool-down during which, on many machines, a warning buzzer sounds to let you know that you will have to remove clothes soon. This is because permanent-press and wrinkle-resistant clothes, when warm, may wrinkle if left to sit in the dryer, and they may even do so if they are only slightly warm after the cool-down. If your machine offers only temperature and time choices and no preset cycles, when drying permanent-press clothes you should generally choose a “medium” to “low” drying temperature and a wrinkle-preventing feature. The latter keeps the clothes tumbling without heat for an extended period, until you take them out and fold them, so that they do not wrinkle from sitting in the drum. With permanent-press articles the wrinkle-preventing phase is especially important, but it is helpful to reduce wrinkling in cottons, linens, and knits, too. Wrinkle-prevention options are useful features that many people fail to take advantage of. If your machine has none, try to remove the clothes from the dryer and fold them immediately.

“Air fluff” or “fluff dry” simply uses unheated air. It can be used to fluff pile fabrics or knits or to dry plastic shower curtains, diaper liners, and other items that should not be exposed to heat.

Avoiding Overdrying; Damp Drying. Success in using an automatic dryer consists in not overdoing it. Overdrying causes shrinking, wrinkling, a harsh, dry hand, and yellowing. Such yellowing is especially problematic for whites, lights, and pastels. On synthetics, elasticity may be reduced and the hand or texture may sometimes be permanently ruined by overheating.

To avoid overdrying, set the temperature and timer conservatively or, when you can, use electronic drying. The longest drying times are necessary for the largest loads and the bulkiest, thickest items, such as towels and blue jeans. Sheets and pillowcases might be dry in less than twenty minutes, but towels can take up to an hour. When you are estimating drying time, remember that a cool rinse extends the drying time. Drying in your automatic dryer also takes longer when the room in which the dryer sits is colder.

You should not aim for absolute dryness. Remove clothes while there is still a hint of dampness in thick seams or at elastic bands. Linen, especially, should never be dried bone-dry; it needs a little moisture to stay supple (and usually requires damp ironing). Blue jeans and other play and work clothes have very thick seams that dry slowly. To get the seams completely dry in the dryer, you would have to overdry the fabric in the rest of the garment, shrinking it, imposing unnecessary wear and tear, tying up the dryer when you need it for something else, and using up energy. So remove jeans and all similar articles when the flat portions are dry, and let them finish drying outside the dryer. Hang them over a clothes rack near the dryer or over a chair back that will not get used, or simply fold them loosely and set them on a table or shelf somewhere.

Sorting for Drying. When drying, you must read and follow care labels carefully. Shrinking, yellowing, linting, pilling, abrading, melting, and other problems can result from using an overhot dryer. Elastic fibers can become inelastic, and white fibers can yellow if they are machine-dried at too high a temperature. Some elasticized garments should not be machine-dried at all.

Just as you cannot wash together items that might bleed color on one another, you cannot dry them together either. Beware of mixing together wet color-sorted clothes in the dryer. Do not dry items that are not colorfast with whites or light-colored loads. All other sorting instructions for washing—instructions as to linting, avoiding damage from buckles and pins, preventing tangles with sleeves, sashes, and trims, removing decorations, keeping matched sets and pairs together, turning inside out to minimize pilling, using mesh bags for delicate and small articles—also apply equally to dryer loads.

Separate slow-drying clothes and linens from quick-drying clothes and linens or stop the dryer midway to remove items that may already be dry. Otherwise, the latter will overdry. Turkish (terry-cloth) towels, blue jeans, heavy work clothes, thicker knits, rugs, and the like dry slowly. Sheets and pillowcases, medium and lightweight woven cottons and linens, and synthetics dry more quickly. (Polyester and other synthetics tend to dry very quickly, much faster than, say, even lightweight cotton knits.)

Keep clothes and linens that are to be dried with a fabric softener sheet separate from those that are not. Softener sheets are most appropriate for synthetic fibers. Fabric softening sheets should not be used on diapers, towels, dish towels, rags, sheets, T-shirts, cotton underwear, and any other articles that must be absorbent to work well and feel good. Fabric softener gives clothes and linens a waxy coating that reduces their absorbency. You will not need fabric softener at every laundering. If you use it too often, it tends to build up and give a greasy feeling. See “Fabric softeners,” in the Glossary of Laundry Products and Additives, pages 81-82.

Usually clothes that need similar washing temperatures also take similar drying temperatures. But if (as a compromise load) you have washed synthetics and wrinkle-treated clothes together with untreated cottons or linens, you may wish to dry them separately so that you can give some and not others permanent-press treatment.

One care label instruction that I sometimes ignore is commonly included on cotton knits—to dry flat. You can buy cotton knit sportswear big enough to fit after some shrinkage; dry it only on low heat, and remove it when still slightly damp. Doing this entails a risk that the garment will shrink more than you predict or that there was some other reason for the instruction besides potential shrinkage, perhaps yellowing or pilling. In the long run, however, you will save a good deal of drying time and are likely to get satisfactory results.

Operating the Dryer. Each time you dry a load, check the lint filter and empty it if necessary. Sometimes it will be necessary to do so in the middle of a large load as well. (Make sure the dryer is off before you do this.)

Choose appropriate temperatures, times, and cycles. Place a fabric softener sheet in the dryer if you intend to use fabric softener. (Try using them only every two or three washes to avoid a softener buildup.) For a small load or for a light softening effect, you can cut a sheet of fabric softener into halves or quarters and use only a piece.

Shake out each wet item to be dried. Then throw it loosely in on the others, one by one. If you throw in clothes from the washer knotted together in an impenetrable mass, they are likely to take forever to dry, or some will overdry while others remain damp because air cannot circulate around them.

If clothes have emerged sopping from the washer, put them back in for another spin if you can or, if you can’t, roll any heavy or thick items in a towel before placing them in the dryer. Otherwise they will take forever to dry.

Remove all clothes from the dryer promptly when they still have a mere hint of dampness. This is especially important for thermoplastic fibers, permanent-press and wrinkle-treated clothes, and cottons that are to be ironed, to prevent or reduce their wrinkling. Remove articles that are to be damp-ironed when they are still fairly damp, roll them up, and then cover them so they stay damp until you are ready to iron. (Linen should usually be dried outside the dryer, but if you put it in and want to iron it, take it out when still very damp. Linen needs to be damper than cotton for ironing.) Many dryers have a damp-dry setting.

Hang or fold clothes promptly upon removing them from the dryer or they will take on wrinkles sitting in the basket. As you do so, shake each one out and give it a snap, as though you were cracking a whip. This helps them to return to their proper shapes. You can greatly improve their appearance and reduce the need for ironing if you finger-press them: smooth the seams, pull shapes straight, unfold edges so that they lie flat, and so on.

When you have folded or hung clothes that are still slightly damp from the dryer, let them stand on a shelf or table for a while if necessary to air and complete drying. Often they dry from their own warmth while you are folding. If they don’t, avoid putting them away until they dry more thoroughly or you will get musty smells in dressers and closets.

If clothes that have dried flat or on the line, such as knits, small rugs, pile fabrics, or sheets, feel stiff or harsh or look wrinkled or flat, put them in the dryer on air fluff (cool air) for a few minutes after they dry to soften and fluff them up.

Unwrinkling with Your Dryer. You can use your dryer to unwrinkle clean, dry clothes (from, say, a suitcase or drawer) by tumbling them on reduced heat for five to ten minutes. It sometimes helps to throw in a clean, slightly damp, nonlinting towel to make a little moisture. You can also steam out wrinkles in a drying closet.

Line-Drying

Our language shows the effect of centuries of drying wet linens and clothes outdoors when we speak disapprovingly of “airing laundry in public” or “letting it all hang out.” Years ago, when everyone had to hang their laundry out on the line, it was common for some people to feel ashamed at the quasi-public display of their linens and underwear, especially if they showed stains and tears. Older friends say that worst of all was hanging out the rags that all women used before the days of disposable sanitary napkins and tampons. Today, it is hard to imagine anyone being embarrassed by their underwear—now that we see billboards of celebrities in theirs. But my suburban friends tell me that you still need a private backyard to line-dry your laundry unembarrassedly because many people think that their neighbors’ laundry flapping in the breeze ruins the appearance of the neighborhood and will complain when they see it.

To my mind, whether laundry on the Une is unattractive depends on what kind of laundry it is and how it is hung. When I was a girl, hanging out the clothes was an art widely understood in the countryside. Familial style was given some leeway, but there were nonetheless ways you did this and ways you didn’t; the rules were so clear that I remember one elderly lady stifling unseemly giggles when she saw the work of a novice. If those days ever come back, the instructions below will save you from social humiliation.

Line-drying outdoors produces appealingly fresh-smelling clothes and linens, and sunlight is a natural sanitizing and bleaching agent. See “Bleaches: Sunlight,” in the Glossary of Laundry Products and Additives, page 70. (The dryer’s heat also kills germs.) Line-drying is good for almost all washables. It is not good choice for fabrics that will stretch when wet, such as wool and loosely knitted articles, and for articles that need fluffing to look their best—terry-cloth, chenille, flannels, and other napped and pile fabrics. Nor should you hang filled articles such as comforters or sleeping bags over the line; the fill drops to the ends, clumps, and will not dry. Items such as towels, which take very long to dry, you may find inconvenient to hang out. Many clothes feel stiff after drying on the line, particularly if there is little wind to blow them soft as they dry. Towels, especially, tend to get boardlike and stiff on the line and need some tumbling to make them soft. You might tumble towels until they are half-dry, then move them to the line for finishing—or vice versa. Knits, too, often need some tumbling (usually on “low” or “cool”) to regain their softness, whether before or after drying flat. Delicate clothes and fabrics should be dried flat rather than Une-dried. Fabrics that should not be exposed to the sun can be line-dried indoors.

Outdoor clothesline

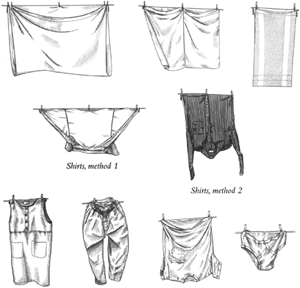

Hanging clothes and linens for line-drying

If you hang things carefully, they will often look smooth when they are dry, and you can minimize or avoid ironing. The best weather for line-drying, if you have a choice, is warm, dry, and sunny with a moderate breeze. You need some wind to billow wrinkles out of the fabric and hasten drying. Line-drying can seem interminable on a humid, airless day. But avoid extremely windy days. The flapping is wearing on the clothes; the wind is hard to work in and sometimes blows clothes off the Une. Avoid freezing weather also. It is painful to hang out wet things in such weather, and they will take forever to dry. Besides, water expands when it freezes; that can result in damage to fabric whose fibers have absorbed water. The idea that freezing outdoors is good for the wash is an old wives’ tale, born, no doubt, out of the superstition that great suffering always produces great good.

Make sure that your line and clothespins are clean. Wash the line, if necessary, with some ordinary detergent in water or household cleaner. Make sure it is sufficiently taut, strong, and secure to prevent the clothes from dragging or dropping.

Keep a plentiful store of clothespins and do not stint on using them. (Look for sturdy ones; some are shoddily made.) You can use old-fashioned wooden push-down pins (no spring) for sheets, towels, play clothes, and other articles that will not pull out of shape or stretch. Plastic clothespins are less likely to leave marks on the clothes—but be sure they are clean. For knits and stretch wear, including underwear, panties, T-shirts, and knit dresses, use clip-on pins (with a spring).

Usually you will turn three or four inches of the fabric over the line, enough to be sure that the fold will not slip or come undone, especially important if there is a strong breeze. Heavy pieces will be more secure if you turn one-third to one-half of them over the line. On windy days, too, turn over more, for added security. Do not let clothes drag on the ground. Be sure that the pin gets a good grip. To the extent possible, hang sheets, tablecloths, and similar flatwork so that their hems are parallel to the line widthwise. This takes less room along the clothesline and puts the stress of hanging on the warp yarns (they run lengthwise), which are stronger than the filling yarns. When hanging blankets or other large, heavy items, lay them over two lines so as to distribute their weight. (See the illustration on page 125).

Hanging clothes properly reduces wrinkles and makes ironing easier. The wind smooths wrinkles and softens and dries clothes quickly, so try to hang garments so that sleeves, skirts, and legs billow out in the breeze. To accomplish this with sheets, pillowcases, skirts, and other pieces with double layers, hang them so that the fold (or the closed end of the pillowcase) hangs down and the open, hemmed edges are pinned to the line; do not pin the fabric taut on the side from which the wind is blowing but let it sag down a bit, so that there is an opening for the wind to enter. (See the illustration on page 93.) Otherwise, however, it is best to pull the pinned edges of the clothes taut to reduce wrinkles. In addition, you should finger-iron and smooth the pinned-up clothes; pull seams, collars, and pockets straight and hang items so that the Unes of their construction run neatly parallel and perpendicular to the clothes-line. Otherwise the clothes will dry with funny bumps and shapes.

To prevent fading, dry colored clothes in the shade or turn them inside out, or both. White linens usually benefit from drying in direct sunlight, which gives them a gentle, natural bleaching. White and light cottons may eventually yellow with prolonged exposure to sunlight, so some experts recommend that they be hung in the shade for drying. My view is that the more typical effect of sun on white cotton—for, say, an afternoon on the clothesline after each laundering—is to bleach it, which I like.

Sheets: Fold the sheet hem to hem, then fold 3 to 4 inches of one hem over the line and pin at both ends. Pin the corners of the other hem a few inches inside the first two. The sheet should open toward the wind so it blows out like a sail. Run your hands down the selvage edges to smooth them and make sure that the sheet is hanging square and even.

Pillowcases: Fold one side of the opening over the line, pinning at both corners, allowing one side to sag open. You want the pillowcase to fill up like a sail in the wind.

Handkerchiefs: Fold in half over the Une and pin at both ends. Towels: Fold three to four inches of one end over the line and pin at both corners. Towels will line-dry to be much softer and fluffier if you shake them energetically before you hang them on the line. Make them snap. This loosens up the pile very effectively. Shake and snap them when you take them off, too, to soften them.

Shirts and Blouses: Method I—hang by the tail, turning under three to four inches over the line, fronts opened out to the sides. Pin at placket ends and side seams, if necessary. Method 2—hang by the tail, turning under three to four inches, but fold the fronts in.

Dresses: If the dress is straight, pin it by the shoulders. If the dress has a full or gathered skirt, pin it by the hem, shoulders hanging down. But straight dresses and the tops of many full dresses dry with fewer wrinkles and a better shape if you hang them on hangers.

Skirts: Turn over the waistband of straight skirts and pin at both ends. Hang gathered or full skirts by the hem.

Pants and Shorts: Turn the waist over and pin at both ends, or, for pants, use a trouser frame.

T-shirts and Undershirts: Fold the hem a few inches over the line and pin at both ends.

Underwear or Panties: Fold the waist over the line and pin at both sides.

Bras: Pin by the hook end.

Socks: Pin by the toe.

Hangers: If you want clothes on hangers to dry outside, make sure they will not blow off the hanger. Sometimes you can pin them on at the shoulder, but this may leave holes in fine and light fabrics, so be careful. If you hang a hanger outdoors—on the clothesline or elsewhere—watch out that it does not blow off. Try pinning the hanger to the clothesline with a clothespin, making sure that the garment is securely fastened to the hanger.

Where it will not make a thick lump of cloth that will take too long to dry, it is labor-saving and space-saving to pin the ends of two garments together so that you use only half as many pins. For example, you pin a pillowcase to the end of a sheet and then pin a second pillowcase to the end of the first, creating a continuous line rather than one with breaks between the items. (See the illustration on page 92.) But you cannot let two items touch if one has bleeding dyes that would be visible on the other.

Remember that clothes dry at very different rates. If you are short on line space, run out to check on the clothes periodically to see whether some are dry. Sheets dry very quickly in the breeze and take up lots of line. You’ll soon be able to take them down and hang up other things. Line-dried clothes are unlikely to get overdried on the line, since they are not exposed to artificial heat, but do not leave them out on the Une overnight. Articles that are to be ironed should be taken down when they are still a bit damp, rolled up, and covered with a towel or placed in a plastic bag so that they do not dry out. Iron them promptly so that they do not rot or mold.

Fold immediately all clothes that will not be ironed. As you take down clothes for folding, shake each item and snap it—that is, hold it at one end and sharply crack it like a whip. This fluffs and shapes the article. Avoid putting laundry in a basket unfolded, and especially never leave it that way for a period of time, for this will cause much wrinkling and ruin the good effects of your careful hanging.

If you are line-drying indoors, be sure to shake out the clothes vigorously before hanging them. This is necessary to reduce wrinkles and help them to dry less stiffly since you have no breezes to soften them.

Hanging Dry on Hangers or Hanging Racks

Dresses, blouses or shirts, jackets, permanent-press clothes, and pants that do not go in the dryer are usually best dried on hangers, for this preserves the shape of the garments and reduces wrinkles. Other items can be hung on clotheshorses. Wash-and-wear or drip-dry clothes should always be carefully hung to dry and finger-pressed (smoothed and straightened), particularly at seams. It is usually best to hang clothes to dry on wide hangers, for this distributes the weight of the garment better. A thin wire hanger produces strain on a very narrow band of cloth and creates unwelcome creases around the shoulder area. Jackets should be hung on hangers designed for jackets, which have wide rests for the shoulders. There are also thick-padded or inflated plastic hangers that are good for drying.

When drying dresses, blouses, and shirts, hang the garments straight and smooth. Hang slips and dresses by their straps, if they have them. Button, zip, or snap them up so that the cloth is pulled properly to shape the garment. Press or smooth collars, facings, seams, trim, and pockets with your fingers, especially on wash-and-wear clothes. This little step can make ironing of many garments unnecessary and reduces it considerably on all. Use a trouser frame for “hanging” pants. This pulls them taut so they do not wrinkle and creates a crease in the right places. Or hang them over a wide hanger. (If you hang them from their cuffs on a trousers hanger, the cuffs may not dry.)

Jacket on hanger

Nonrusting hangers with broad shoulders are best for hanging clothes to dry

Dripping garments can be hung in the bathtub or shower stall, either on a drying frame or a Une. The stores are full of good gadgets for these purposes.

Underwear, hosiery, and other articles that do not need to be hung on a hanger can be hung on racks.

Indoor drying on hangers and racks can be speeded by turning an electric fan on the clothes.

Drying cabinets provide for both hanger- and shelf-drying. Be sure to choose an appropriate heat level.

Drying Flat

Clothes that must be dried flat rather than hung include fabrics that stretch when wet, such as many knits and wools, and very delicate articles that should not be pinned or blown on the line or that should not be subjected to the stress of their own weight during hanging. In addition, smaller articles, particularly knits and items made of fast-drying synthetics, such as panties, bras, or hosiery, dry so quickly on a frame or rack that there is little reason to expose them to the high temperatures and static-producing friction of a dryer. They will last longer and look better dried flat.

When drying clothes flat, keep them away from direct sources of heat, which may produce shrinking. Dry colored items out of direct sun. Pick a warm, dry room in which the air will readily take up moisture, or, if drying outdoors, a warm, dry day. Knits, especially sweaters and other garments that hold lots of moisture, should be laid on a mesh rack, which speeds drying by permitting air penetration from below as well as above, or on a thick, absorbent towel. (If the article to be dried bleeds color, choose a towel that does not matter or that is of like color. And be sure that you do not lay the drying article on something that will bleed color onto it.) Articles that do not hold a great deal of moisture, such as panty hose or panties, can be laid on a sheet. Whatever you are drying, be sure to protect wood or other surfaces that might be vulnerable to moisture if there is a chance that moisture will soak through or drip onto them.

Drying rack

Flat drying rack

If you turn over long-drying items, they will dry faster, but you should not disturb carefully blocked articles such as sweaters or other wool or knit clothes.

You can hasten drying of clothes laid flat by turning a fan on them.

You can also dry things flat in a drying cabinet or on a drying rack in your dryer. Choose the cycle or heat setting appropriate for the garments. When using an in-dryer rack in my machine, I have to use a time-dry setting rather than a moisture-sensing setting; the dryer does not seem to sense the moisture in a single stationary item.