The time after the Roman withdrawal and before the Norman invasion is known archaeologically as the Early Medieval period, and can be further subdivided into the Anglian (AD 410–866) and Anglo-Scandinavian or Viking (AD 866–1066) periods. It includes a short length of post-Roman indigenous rule and ends with the unification of England into a single kingdom. The objects recorded from this period are many and varied, displaying the different decorative styles of distinct cultures.

The immediate post-Roman era is unclear archaeologically, as native Britons under Roman rule are virtually indistinguishable from those ruling themselves. How long, and in what form, Roman structures of administration persisted after the army left is unclear. An ever-shifting, complex pattern of small, warring kingdoms emerged.

Following the Roman withdrawal, Yorkshire was attacked by Picts, Scots and Anglo-Saxon raiders. The Germanic invaders consisted of two main groups: the Angles (or Anglians) from modern north Germany, and the Saxons from the modern German-Dutch border. The Angles settled in eastern Britain, including Deira (modern East Yorkshire) and East Anglia, while the Saxons adopted territory further south. Deira was disputed territory claimed by both Angles and Saxons. It eventually joined with Bernicia, to the north, to form a single kingdom of Northumbria, which stretched from the Humber to south-east Scotland. Following battles in Hatfield and Winwaed (believed to be in Yorkshire) in the seventh century, the unified kingdom expanded, incorporating Elmet and uniting Yorkshire and the wider north.

During this period, aristocratic status was defined by the ability to muster wealth and give extravagant gifts to other leaders. Some of the objects in this chapter reflect this gift-giving tradition. The Anglo-Saxon fashion for objects of gold and garnet is clearly demonstrated in the famous Staffordshire Hoard.

By the mid-ninth century, England had unified into four independent kingdoms: East Anglia, Wessex, Mercia and Northumbria. From the late eighth century, it suffered sporadic attacks by Scandinavian raiders known as Vikings. In AD 865, the Great Danish Army, led by Ivar the Boneless, landed in East Anglia, seeking new territories. This was not a band of opportunists, but a large and organised army. Heading north, they seized York, which was a prosperous trading settlement, and made it their capital, Jorvik. The Vikings eventually took control of the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms and, by AD 874, only Wessex, ruled by Alfred the Great, remained under Anglo-Saxon control. Ultimately, England was divided into the Anglo-Saxon south-west and the Viking north-east, known as the Danelaw.

While popular perception suggests that the Vikings were attacking and conquering raiders, there is a range of evidence suggesting that they were also farmers, traders and craftspeople. Increasingly we are learning that Vikings were very adaptable, raiding and trading interchangeably.

The Anglo-Saxon leader Athelstan succeeded to the kingdom of Northumbria in AD 927, becoming the first king of England with authority over all of Britain. This is celebrated on coins, which use the title: ‘Rex TOtius BRItanniaE ’ (‘King of all Britons’).

Almost ninety years later, Cnut the Great, king of Denmark, Sweden and Norway, conquered England, placing Yorkshire under Viking rule once again, along with the rest of England this time. Cnut’s empire, bridging the North Sea, made him one of the most powerful men in Europe.

A map showing some of the post-Roman, Anglian and Saxon kingdoms of England and Wales. (Ian Downes)

Several object types are distinctively Anglian, including this girdle hanger from Kilham, East Riding. Girdle hangers date from the sixth century and are associated with Anglian women. They appear to be imitation keys or latch-lifters, which were worn suspended from a belt. They may have emphasised the woman’s status as mistress of the household (FAKL-508584).

Some of the stunning artefacts from the Staffordshire Hoard. Many of the objects in the hoard would have been given as gifts to reinforce the social status of the giver and recipient. (WMID-0B5416/2009T394; for more information see http://finds.org.uk/staffshoardsymposium )

A map showing the Danelaw and the Anglo-Saxon part of England. (Ian Downes)

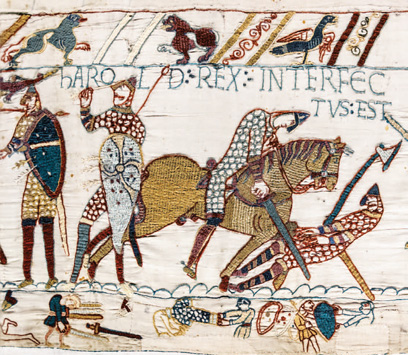

In AD 1066, following the death of Edward the Confessor, Harold Godwinson became king of England. He defeated a Scandinavian army seeking to reclaim Cnut’s kingdom at the Battle of Stamford Bridge in September of the same year, allowing William of Normandy to take advantage of the distraction and invade the south coast. Weakened by his exploits in the north, Harold was defeated just nineteen days after the Battle of Stamford Bridge by William at the Battle of Hastings. This event was the turning point that marks the end of the Early Medieval period.

A penny describing Athelstan as ‘King of all Britons’ with the legend EÐELSTAN REX TO BRIE . This coin was recovered from the Vale of York Hoard. (York Museums Trust (Yorkshire Museum) [CC By-SA 4.0] accession number YORYM:2009.55.639)

The death of Harold at the Battle of Hastings, as depicted on the Bayeux Tapestry. (Myrabella (Own work) [Public domain or CC0], https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Bayeux_Tapestry_scene57_Harold_death.jpg )