Because the Osprey hunts by plunging into water, its nostrils are slit-shaped and more horizontal than other raptors.

Many raptors have a crest, while others have a white base to the crown feathers, which are raised when the bird is scared or concerned. Some have markings on the back of the head that resemble another pair of eyes, perhaps to confuse other predators. Falcons have bony baffles in their nostrils, which may help in reducing airflow through them during high-speed stoops. Some diving raptors have slit-shaped nostrils to reduce the entry of water. The ear openings are just behind and below the eyes and only visible on raptors with exposed head skin, such as vultures. Owls, and to a lesser extent harriers, have a flat face or facial disk that helps channel sound to their ear openings.

Because the Osprey hunts by plunging into water, its nostrils are slit-shaped and more horizontal than other raptors.

The Golden Eagle has larger nostrils as they don’t need to keep out water.

The eyes of diurnal raptors are set on either side of the head, facing forward. An upper and lower eyelid and a “nictitating” membrane protect the eye. Some species have a bony ridge above and to the front of the eye, which both protects and shades the eye. In owls, the eyes are situated at the front of the head and diverge outward slightly.

Lower eyelid

Upper eyelid

Nictitating membrane

The eyesight of birds of prey is between four and eight times better than that of humans. When scanning into the distance they can see eight to ten times farther than man. Some raptors can spot a grasshopper at 109 yards (100 m) and others can detect a vole or lizard at 437 yards (400 m) and a rabbit at 0.62 mile (1 km). Many owls hunt after nightfall, and although some use their exceptional hearing abilities to locate and catch prey, their eyesight in darkness is between 10 and 100 times better than man’s.

The bill is strong and hooked and is used for ripping up flesh into smaller, gulpable pieces. The sharp edges of the bill act like knives to slice through flesh. With the prey securely clamped under its feet, the raptor can pull off chunks of flesh by burying its hooked bill in the flesh and straining up and backward. Some falcons have a “tooth” in the upper mandible, used both to kill prey with a bite to the neck, and for taking apart insects. Some kites have two “teeth.” The bird’s beak, or bill, is made of bone and covered by horny plates of a tough fibrous material called keratin. Some have huge bills for chopping up large chunks of flesh, whereas others can have quite small ones for picking at little bits of meat. At the base of the upper bill is a soft, fleshy area known as the cere. The absence of feathers below the raptor’s bill is for hygiene reasons, as they would get caked in blood and would be difficult to clean. Owls have beaks that are relatively small and are not generally used for pulling apart flesh as they tend to eat prey whole.

Peregrine

Egyptian Vulture

Snail Kite

Raptors’ legs are used for walking, running, jumping, perching, and grasping, and often for killing prey. The legs and feet are covered with scales, and each foot has four toes. In most owls, the feet are not bare but are covered with feathers, as their feet do not become as messy as those of other raptors. Raptors usually have the first toe pointing backward and the other three pointing forward. At the end of each toe is a claw, or talon, which curves downward and is made of keratin. The hind toe and inside toe are especially strong, with longer talons, and are used to crush and kill prey. The other two toes are used for balance when perched or walking. The feet are adapted for the species’ diet: those of raptors that hunt slippery fish can have spikes, while those of birds that prey on stinging insects can have extra-hard scales. Vultures have weak toes and talons as they do not need to kill and catch prey. Raptors such as the Golden Eagle, which carry large prey, have a particularly long hind claw. Some falcons use the hind claw to strike down other birds in midair.

Some raptors that catch birds in flight have the aid of an elongated middle toe, like the Sparrowhawk.

Eagle Owl foot: Non-fishing owls tend to have feathered feet.

If you spend any time bird watching you will have noticed that when you spot a bird of prey it is often flying. To help identify it when it is soaring up high, gliding away from you or dashing past, it is useful to observe its shape and size as well as the color of the plumage. Eagles, hawks and vultures, or buzzards, have long, broad, rounded or blunt-ended wings for soaring. Falcons have thin, pointed wings perfect for high-speed stooping. Some falcons have a broad base to their wings, which makes them excellent at soaring. Sparrowhawks and goshawks have short, rounded wings for making quick, agile flight maneuvers. Look at the tail shape. Is it long and thin, as in falcons, or forked, as in most kites? Although owls come in many sizes, most appear blunt-headed, with rounded wings and short tails.

Goshawk

Falcon

Eagle

Tails are used to create lift and balance in flight, as a rudder for turning, and as a brake for landing. Tail shape and length vary in relation to how the bird catches its prey. Raptors that need to twist and turn through forest canopy tend to have longer and broader tails than birds that make mad dashes after their prey.

The kite’s distinctive tail really helps this large bird to fly with great agility.

The buzzard’s tail is a more typical bird of prey shape.

The kestrel’s tail fans out to help when hovering.

Raptors hold their wings in different ways depending on whether they are gliding, soaring, stooping, or flapping along. When kites and harriers flap along, their wings are swept backward and appear angled. Harriers also hold their wings up in a distinctive “V” shape when gliding, which is especially obvious when seen flying head-on. In contrast, kites, head-on, are similar in shape to a flattened “M.” Falcons have long, straight, pointed wings in normal flight, but during stoops the wings are closed up against the body. Eagles and vultures hold their wings out straight when gliding or soaring, although, when seen head-on, slightly different angles can be distinguished. For example, when gliding, the wings of the White-Tailed Eagle slope down slightly while those of the Golden Eagle are slightly turned up at the ends. Owls have straight, rounded wings.

Harrier flight

Eagle flight

Owl flight

All birds of prey and a few other birds, such as herons, kingfishers and curlews for example, regurgitate indigestible material. These are called pellets and are formed in the bird’s gizzard. They can contain a mixture of bones, fur, feathers, bills and bits of insects. Fresh pellets can look shiny, this is from the coating of mucous the bird needs to aid regurgitation. Pellets are normally ejected within two days of the meal, although in some cases they can take up to five days. Some birds of prey are better than others at digesting small bones, therefore a pellet is not always needed. Scientists can learn a lot about the bird’s diet from pellets. Sometimes you can find whole skulls, teeth, and many bones; this enables identification of exactly what creature the bird has eaten.

Barn owl pellet

Falcon pellet

Prey is the meat eaten by raptors and can come from mammals, birds, reptiles, amphibians, and fish, or from nonvertebrates such as crabs, mollusks, and insects. The prey can range in size from a rotting elephant or blue whale carcass at one end of the scale, to worms and insects at the other. Most hunting attempts, except those for insects, end in failure, but after a successful attack the raptor will spread both wings over the prey as it feeds. This is called the mantling display and it may reduce the possibility of other species stealing the food. The fur, feathers, and other indigestible remains are regurgitated as pellets via the mouth. Research has shown that some birds of prey can reduce the numbers of its prey species within its territory. Some raptors are attracted by gunshots, in the hope of finding dead or injured prey.

Vultures feast on a dead cow.

Birds of prey are at the top, or nearly at the top, of their respective food chains. Some smaller raptors have to keep an eye open for larger raptors with a diet that could include them on the menu. As with all animals, they can be prone to dying from diseases. The very recent collapse in the population of vultures in India is thought to be due to the spread of a lethal pathogen. The most significant threat by far, however, is from man, through habitat destruction, hunting, and the use of pesticides. Collision with power lines and moving vehicles can be added dangers. Surprisingly, despite these threats, no birds of prey have so far become extinct during our lifetime. Many, though, have come perilously close and still have a precariously low population. After massive falls in the numbers of some species in the second half of the twentieth century, many populations have recovered to former levels. Most birds of prey in the USA are protected by federal laws that prohibit hunting by humans. Conservation of natural habitats in which the raptors can hunt is vital.

The California Condor is possibly the most endangered bird of prey in the world. Once their greatest threat, man is now trying to save this species from extinction.

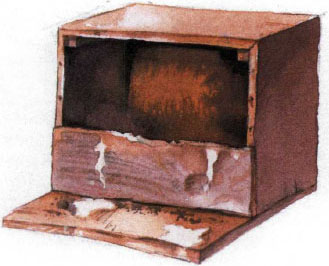

The nest is used as a safe place to lay and incubate eggs and rear the young. Some birds of prey do not really build a nest but just lay their egg or eggs on a scrape on the ground or cliff ledge, or in a hollow in a tree. Others will construct huge nests from sticks and small branches, which are used year after year. New nesting material is added each year, so that after a few years the nests can become colossal and, in some cases, in danger of collapse. Some species will reuse abandoned nests built previously by other birds, including other raptors. Some nests are merely a platform constructed from sticks. Often a nest will be lined with softer material such as green leaves, small pieces of bark and moss, or covered with material so that they are camouflaged and therefore difficult to spot. Many species nest in trees, often in the crook of a large fork, while others will nest at the end of fine branches to avoid attack by predators. Many species of owl and some other raptors will nest in boxes provided by man.

Hen Harrier nest

Eagle nest

Raptors can survive in any habitat, providing they can find enough food to eat and a safe place to roost and nest. As most habitats will pass these three tests, birds of prey are found on every continent except Antarctica, and can be seen in almost every type of habitat, ranging from Arctic tundra to tropical rainforest and sun-scorched deserts. Some species can even survive in urban habitats, and others will make use of man-made structures such as pylons and ledges on buildings for nesting. Some species of raptor can exploit a wide variety of habitats, while others are more specialized and restricted to one habitat. This is often a reflection of their diet. The least fussy eaters can survive in all sorts of habitat, whereas for others the choice is more restricted. The Snail Kite, for example, eats only a certain type of snail and is therefore limited to the freshwater marshes in which the snail is found.

Owl box

Many species of raptor migrate, including several species of owl. Migration is the movement from one area to another and enables the migrants to exploit new food sources as they become available, such as when the ice retreats in Arctic regions in summer. In general, species in the northern hemisphere follow the seasons, moving north in the summer and retreating back south in the winter. In some species one of the sexes can be migratory while the other stays put, and even within the same species, some populations can be migratory and others resident. They are partial migrants. Some species are nomadic, flying from area to area in search of food. When a good food source is located they stay for a while until the prey have been thinned out and then they move on.

Raptors often travel along migration routes, following ridges and coastlines. Large numbers can be seen in some locations, especially when they are funneled into bottlenecks, often where there is a narrow sea crossing. Many raptors do not like to travel over water. In general, small birds that can flap their wings for longer are less reluctant to cross open water. Larger species soar up high using updrafts, glide down, covering huge distances, and then use another thermal to gain height again. This method would not work over water, due to the absence of thermals, which develop only over heated-up land. Most raptors fly during daylight hours, coming in to land at night to roost.

Migrating birds are believed to have an “internal calendar” that tells them when to start migrating. Factors such as the change in the length of daylight each day will influence them. They navigate by making use of several bits of information gleaned from the earth’s magnetism, the position of the stars, moon, and sun, and the low sound waves emitted from mountain ranges, as well as by using geographical features and, possibly, an inherited internal map.

Birds are vertebrates, or animals with a backbone. Other vertebrates are mammals, reptiles and amphibians, and fish. Birds can be separated from some or all of the other vertebrates by the following features: they have feathers, wings, beaks, and scales on their legs and feet; they are warm-blooded; and they lay eggs. They have been given a scientific class, Aves, which comes from the Latin word for bird, avis. Birds can then be further divided into different orders, two of which are birds of prey: Falconiformes (mostly day-flying raptors) and Strigiformes (owls). The Falconiformes are divided further into four groups, called families. These are the Cathartidae (New World vultures), the Accipitridae (hawks, eagles, harriers, kites, Old World vultures, and the osprey), the Sagittariidae (secretary bird) and the Falcones (falcons and caracaras). The Accipitres family has the greatest number of species. The Strigiformes are divided into just two families, the Tytonidae (barn owls) and the Strigidae (typical owls).