Chapter One

October 26th 1911. Emma knew she would never forget the date – she was as sure of that as she was sure of her love for Seth.

‘But we were both born in this parish,’ she said. ‘We’ve lived here all our lives. My parents were married in this very church. Seth owns a fishing fleet and gives local men a living. Houses them. So what do you mean you can’t marry us?’

Emma gripped Seth’s hand tightly for support.

‘As you heard, Miss Le Goff.’

‘But you’re a vicar. It’s what vicars do, marry people. I’m eighteen, Reverend Thomson, old enough to marry. I know I’m an orphan and can’t get my papa’s permission, but I’m sure Dr Shaw will speak for me if—’

‘Let it go, Emma,’ Seth said.

‘You’d be wise to take heed of what your fiancé tells you, Miss Le Goff. Now if you’ll excuse me, I have other people to see.’ The Reverend Thomson heaved his bulk out of his high-backed over-stuffed chair and walked towards the bell pull.

Huh, Emma thought, it’s as though we’re not fit for his company. Well, she hadn’t said all she wanted to say to the Reverend Thomson yet.

Emma prised her hand from Seth’s and raced across the room to put herself between the vicar and the bell pull. He resolutely refused to meet her eye. But whichever way he looked, Emma dodged in front of him. Faced him. Challenging.

‘Is that can’t or won’t marry us?’ she asked. ‘Just so as we know before we leave.’

The Reverend Thomson sighed heavily. ‘Joining a couple together in holy matrimony is always at the discretion of the vicar. If I feel a couple doesn’t understand the sanctity of marriage, or there are … are … other reasons, I …’

Seth took advantage of the hesitation.

‘Are you referring to my family, Mr Thomson? My late brother, Carter, perhaps?’

The vicar turned around slowly to face Seth. ‘Not particularly, no. But that is in the equation. I’ve heard, on good account, that you, Miss Le Goff – a single woman – lived under the roof of one, Matthew Caunter. And—’

‘I was his housekeeper, Mr Thomson. Did no one bother to tell you that? You have a housekeeper yourself. And no wife. Do people make assumptions about that?’

‘I don’t think—’ Mr Thomson began, but Emma wasn’t finished yet.

‘Mr Caunter took me in and gave me employment when no one else in this town would. They were all, including those who go to church regularly, shunning me. Well, all except Seth, of course.’

‘That’s as may be,’ the Reverend Thomson snapped. ‘Just as serious is the fact that there’s a shadow of doubt hanging over your late mother, Miss Le Goff.’

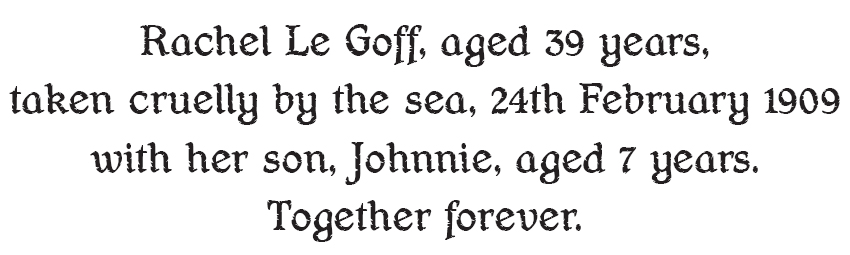

‘The coroner’s verdict was “accidental death by drowning”,’ Emma said wearily – oh, to have a sovereign for every time she’d had to tell someone that.

‘And I have a letter, written by my brother, Carter, confessing to having …’ Seth began. He went to stand beside Emma, putting an arm around her shoulders. ‘I’m sorry, sweetheart, but I have to say this,’ he whispered to her. ‘My brother, Reverend Thomson, confessed to having been party to Rachel Le Goff and her son Johnnie falling from the cliff. Mrs Le Goff was running away from him. I can show you the letter.’

‘Do you think anything a murderer might have to say on the night before he went to the gallows would hold any sway with me?’

‘How dare you!’ Emma was white hot with rage now. ‘What Carter Jago was isn’t Seth’s fault! And the coroner’s verdict was good enough for the Reverend Toop at the time. He gave my mama and Johnnie a lovely funeral. The whole town turned up.’ She glanced at Seth. His pa and his brothers hadn’t been there, but Emma had glimpsed Seth afterwards among the gravestones, solemnly watching as her mama and Johnnie were lowered into the earth. ‘Almost the whole town.’

‘The previous incumbent was obviously a softer touch than I am. Now, if you’ll excuse me.’

The Reverend Thomson sidestepped Emma and Seth and walked to the door. ‘I’ll have Mrs Dunn show you out.’

‘We’ll find our own way,’ Seth said.

‘Yes,’ Emma agreed. ‘And we won’t be back. Not ever.’

‘Did you mean that?’

Emma, her arm through Seth’s, leaned into him. They were walking the gravel paths of the cemetery, habit taking them to family graves: Seth’s mother’s, with its ornately carved headstone; and Emma’s pa’s, with its far simpler tablet; and her mother’s and Johnnie’s, the same as her pa’s but with a dove etched over Johnnie’s name. Seth had had them made for Emma because she hadn’t been able to afford them herself at the time. A surprise. A gift. A testimony to his love for her.

‘Every word. I’m never going to the rectory again, no matter what. Or the church. But we’ll have to come here, won’t we?’

They’d reached her mama’s and Johnnie’s joint grave now. It didn’t seem possible that it was over two years since they’d been laid to rest. Emma bent to trace her finger along the wording.

‘And we will. We’ll come at night, sweetheart, if the Reverend Thomson puts his sexton on watch to keep us out during the day.’

Emma wanted to laugh because the thought of her and Seth creeping about the cemetery in the dark trying to find the graves was a funny idea. But the laugh wouldn’t come.

‘I wanted to lay my wedding bouquet here,’ she said, a catch in her voice. She knew exactly which flowers she would carry on her wedding day – wild flowers if there were any to be had, and if not stocks; heady musky-scented stocks. White ones for preference. And a white bud rose as a buttonhole for Seth. ‘So my mama was part of our day. And I thought you could put your buttonhole flower on your ma’s grave and—’

‘We still can,’ Seth interrupted. ‘There are other churches. The Baptist chapel?’

‘No! I’ve never been a Baptist. Baptists are too sanctimonious my mama always said, saying you can’t have a drink of sherry – even at Christmas – or put brandy in your puddings. Besides, I was christened in this church. I don’t want the Reverend Thomson and his narrow-mindedness forcing us into something we don’t want. I’ll know when I see the right place for us to marry.’

‘But we’ll marry soon,’ Seth said. ‘I love you and want to make a statement to the world to say so.’

‘Oh, Seth, you say the loveliest things.’

Emma felt her eyes welling with tears. She was already emotional from their unpleasant confrontation with the Reverend Thomson, but now she was overcome by her feelings for Seth; an emotion that began somewhere behind her breastbone and radiated outwards with warmth. And it wasn’t just his looks – jet-black hair, and skin that looked as though he’d been out in the sun all day, even in winter; eyes the colour of ebony almost. How delicious it was to stand on tiptoe to reach his lips and kiss his full, soft, mouth. She had to pinch herself sometimes that Seth had chosen her when there were girls from richer backgrounds he could have chosen.

‘All true, sweetheart,’ Seth said. ‘I won’t have people talking about you, blackening your name.’

‘Any more than they already have! It’s only words, Seth. Words can’t kill me. I won’t let them.’

Emma pulled the collar of her coat tight against her neck. There was a stiff breeze blowing in from Lyme Bay. Slate-grey clouds were hastening the darkening of the sky. Beattie Drew, Seth’s housekeeper, had told Emma that there was going to be snow before Christmas, she was sure of it; she could feel it in her waters. Emma had laughed and said she’d put a bet on it that there wouldn’t be, because it rarely snowed at the water’s edge and she was certain she wouldn’t lose her money.

‘Come on,’ Emma said, chuckling just thinking about Beattie Drew with her mop of curly grey hair no brush or comb could tame, and the funny things she said. Mrs Drew wasn’t going to find it so funny being denied the chance to wear a new hat for Emma and Seth’s wedding though. ‘Let’s get back to Mulberry House. The dining table was delivered yesterday – I want to see how it looks all set up for dinner.’

Not that they would be eating there. Seth still lived at his old family home, Hilltop House, and Emma in one of his properties, Shingle Cottage. But they’d be in Mulberry House soon – just as soon as they were married, and then Seth would put Hilltop House up for sale.

‘Let’s,’ Seth said. ‘You do like it, don’t you?’

‘Mulberry House?’ Emma asked, and Seth nodded. ‘You know I do.’

Seth was full of surprises – buying Mulberry House for one. Just imagine, Emma had thought at the time, what it would be like to go out and buy a house the same way as other, less well-off people went out to buy a packet of tea. But he had. And he’d been happy for Emma to choose the furnishings for it. And as for the fitting out of a stable beside it into a bakery for Emma, well, it still felt like a dream to her at times, that he’d done all that.

On impulse, Emma threw her arms around Seth’s neck and kissed him long and hard. She hoped her mama’s spirit was around somewhere and would be able to sense that Emma had found the love of her life.

‘The Reverend Thomson might have refused to marry us, Seth Jago, but I’ve got a plan.’

It didn’t take Emma long to put her plan into action. By November 18th she was all set. Seth was always encouraging her to spoil herself with lovely things – giving her the money to buy them with – and now she had. At Bobby’s department store she’d bought some deep lilac shantung, just a few shades away from purple; it had cost five guineas, and she’d made it into a wedding dress for herself.

Her mama – skilled with a needle – had made dozens of wedding dresses before her untimely death. Most of them had been white and if Emma closed her eyes and thought hard, she could still see them, draped in old sheets, hanging like ghosts from the picture rail, waiting for the brides to collect them. ‘Make one for me, Mama,’ the young Emma had begged often. And her mama had promised that yes, she would when the time came. But for her mama that time never came.

So Emma had made it herself on an old treadle sewing machine borrowed from a neighbour; one of the few neighbours who believed the coroner’s verdict and didn’t shun her as many in the town still did. Emma had surprised herself at how well the dress had turned out.

‘You’re mad, you are,’ Seth said. ‘But I still adore you.’

Emma fiddled with the red carnation in Seth’s buttonhole.

‘Just one thing, though,’ Seth said. ‘Not so long ago, when I first asked you to marry me down on Crystal Cove, you said you wanted wild flowers, or white stocks for your bouquet and a white rose for my buttonhole and now—’

‘I know. And we will have all those things one day. But for now, we’ll have this.’ Emma pulled off a damaged petal from Seth’s rose and dropped it onto the grass. ‘My, but you look good enough to eat. And I adore you so much I might just take a nibble later.’

‘Emma! This is holy ground!’ Seth waved an arm in an arc out over the graveyard that was like so many others attached to country churches, yet was totally unfamiliar to them. Emma’s plan had amused him, even though he’d done his best to talk her out of it.

But he was going along with it. Emma had known he would.

‘The photographer’s coming. Look!’ Emma pointed to the bend in the lane where she could see a man in a tall hat driving a pony and trap daintily towards them. ‘Don’t I look like every inch a bride?’ Emma said, laughing.

‘Fishing for compliments?’ Seth asked, smiling down at her.

‘Of course! It’s a bride’s prerogative.’

Something fizzed and tickled inside Emma – like sherbet dropped into a glass of lemonade – she was so happy.

‘You look wonderful, and you know it, in that dress.’

‘Thank you, kind sir.’ Emma giggled. ‘I know it was expensive but I can always cut it down to make dresses for our daughter, when we have one.’

Although she hoped that wouldn’t be too soon. She had a business to get off the ground first. A couple of years maybe, but if one came along before then, well … she’d think about that if it happened.

‘And do you like my bridal bouquet, Seth Jago? Isn’t it beautiful?’ She waved her trailing bouquet of deep red roses at him.

‘It is. And you look beautiful. But then you looked beautiful to me that day when you turned up at Shingle Cottage in clothes that were torn and too big for you and—’

‘I accept the compliment, thank you. But I want to forget all that. Once our wedding photograph is in a silver frame on our mantelpiece at Mulberry House, I’ll make sure the local gossips know about it.’

Seth laughed. ‘I can see life with you is never going to be straightforward. That photographer didn’t bat an eyelid when you told him the photographs taken on our wedding day didn’t come out, so we want to recreate them today.’

‘Minus guests,’ Emma said, with a wry smile. ‘I did wonder if he might guess we were up to something when I said our guests were all struck down with the influenza.’

‘What an accomplished little liar you are,’ Seth said, kissing her cheek so she’d know he didn’t mind.

‘I prefer to call it bending the truth to save my skin,’ Emma told him. She’d had to do it often in the past and she hoped this would be the last time she’d ever have to do it. ‘It probably won’t be very long before the Reverend Thomson comes calling at Mulberry House wanting a donation for some good cause or other.’

‘And he’ll leave empty-handed?’

‘I don’t know. I haven’t thought that far ahead.’ Emma shivered. Even though her dress was lined with winceyette and was high-necked and long-sleeved, it was doing nothing to keep out the cold. Her coat was draped over a headstone. ‘If it’s for orphaned children then I probably will donate something, but if it’s for vicars down on their luck then he’ll get shown the door.’ Emma giggled again. ‘Now, start practising your smile.’

But Seth wasn’t smiling.

‘What’s the matter? Don’t you want to marry me any more?’ Emma felt a frisson of fear ripple up her spine that Seth might be changing his mind, that she’d gone too far with this subterfuge. She twisted the wedding band Seth had bought her only that morning around her finger.

‘Of course I do. And I’ve also bought you this.’

Seth took a ring from the pocket of his suit jacket.

The sight of it made Emma gasp. A quartered box of diamonds set diagonally on the shaft. Her mother had owned one exactly like it, but it had been missing from her finger when her body had been found.

‘My mama’s ring?’

‘No. But you described it so well I can see I’ve done a good job getting it replicated.’

He slipped it on Emma’s finger next to the wedding band.

‘Oh, Seth,’ Emma sighed. She hadn’t given a thought to having an engagement ring of any sort. That Seth loved her was enough. ‘You’re a surprise a minute.’

‘Not quite up to your standard though. But one thing – I don’t want you to ever lie to me.’

‘I won’t. The truth between us always. Even if it might not be what we want to hear. Don’t worry, Seth. This will work. And it’ll keep the romance alive for us knowing either one of us could get up and leave at any moment. No legal ties to bind us.’

‘Leave you?’ Seth said. ‘Never. I’d rather lose an arm.’

Emma and Seth waited a week before moving into Mulberry House together – just long enough for the wedding photographs to be sent to them. Emma thought it had been the longest week of her life so far – even longer than the time she had lain ill with pleurisy in a neighbour’s house after her mother and brother, Johnnie, had fallen to their deaths.

To wake in Seth’s arms on this first morning, knowing she would be doing so for the rest of her life, had been wonderful. Emma had even suggested, after breakfast, that they go back to bed for half an hour.

‘You’ll wear me out,’ Seth had joked, before telling Emma he unfortunately had no time because he had to leave for an appointment at the bank.

‘So, what do you think, Mrs Drew?’ Emma turned the photograph of her and Seth in their wedding finery this way and that in its silver frame. At last, deciding on the best position, she set it gently on the mantelpiece while Mrs Drew huffed and puffed behind her. While far from being a gossip, Emma knew Seth’s housekeeper wouldn’t be able to resist letting a few of her friends know that Emma was now Mrs Jago.

‘I think whatever recipe it is you and Seth Jago ’ave got for a marriage it’s a good ’un. Look at you! Your skin glows, your ’air shines. Like mahogany after it’s ’ad a good polish it is, that ’air of yours.’

Emma glanced at herself in the mirror over the mantelpiece, and try as she might she couldn’t get the smile off her lips, she was so happy. Being ‘married’ had changed her, made her more womanly. She was no longer the gaunt young girl of a short while ago. Seth’s loving had seen to that.

‘Is it?’ Emma giggled.

‘Didn’t I just say so! You always were a one for questionin’ a body. Those eyes of yours look like conkers after the rain’s been on ’em, all shiny and bright. Look at ’em!’

‘The photograph’s black and white, Mrs Drew,’ Emma said. ‘You’ve got a vivid imagination.’

But all the same, Emma blushed because looking in the mirror she could see that Mrs Drew was right – her skin did glow more these days. And her hair, now she was eating good food, was shiny and full of bounce – too much sometimes when it was a struggle to pin it all up underneath her hat.

‘I didn’t mean in the photograph. I meant lookin’ at you. My old man never gave me that glow.’

‘Mrs Drew!’ Emma said. ‘You’re making me blush.’

‘An’ I ain’t the only one who’s done that. You wuz a long time comin’ down those stairs this morning after I knocked on your front door. Doin’ up buttons and all, like you’d only just tumbled out from between the sheets.’

Emma knew every word of what Mrs Drew said was true. But what she and Seth got up to between the sheets, as Mrs Drew put it, wasn’t up for discussion. Not with Mrs Drew. Not with anyone. Not ever.

‘The photograph, Mrs Drew,’ Emma said. ‘Do you like it?’

Mrs Drew sucked her breath in through her teeth, pretended to scrutinise the wedding photograph carefully.

‘Hmm. I know my eyes ain’t what they used to be but that there dress ain’t white, is it?’

‘No. It’s a deep lilac. I thought it made more sense to have a dress I can wear again.’

‘Oh, that’s what they all say!’ Mrs Drew laughed. ‘’Ere, it’s not a shotgun job you’ve had, is it?’

‘Definitely not,’ Emma said – not that she’d have minded if that had been the case. ‘Now, my wedding photograph. Do you like it or not?’

‘It’s beautiful, Emma, you know it is,’ she said at last. ‘And that dress is the most beautiful I’ve ever seen. I just wish I could’ve seen you in it, that’s all. I know you think it’s the most romantic thing anyone can do, runnin’ off and gettin’ married like that, but I still don’t know why you and Seth didn’t invite me at least. Who wuz the witnesses?’

Emma’s mind froze. She almost stopped breathing. Then with a little cough, she recovered quickly.‘The lady who does the flowers, and the verger.’ Emma crossed her fingers behind her back, praying God wouldn’t strike her dead on the spot for lying. When she still seemed to be breathing air, she carried on: ‘It was all arranged beforehand.’

‘Hah! That’s as mebbe, but I didn’t think Seth was the sort not to remember those as was on ’is side in ’ard times. An’ I told him so.’

‘I bet you did!’ Emma laughed, letting the woman have her little rant. ‘It wasn’t Seth’s idea, though, it was mine. I tricked him.’

Mrs Drew sniffed.

‘I could’ve ’ad a new ’at. Or some new trimmings. Summat to cheer up a winter’s day any rate. I bets I could do with a new ’at more than the lady what does the flowers, and what saw you wed, do.’

‘Oh, Mrs Drew,’ Emma said. ‘I’ll get Seth to buy you a new hat from Gladwyns. They’ve got some lovely velvet ones in I noticed when I was in there last. An early Christmas present. You can wear it on Sundays when you go to …’

Emma left her sentence unfinished. While Mrs Drew would be going to church on Sundays, Emma certainly wouldn’t be. She hadn’t thought all that through either, had she? What was she going to say when people asked why she wasn’t in church, even if it was only at Christmas and Easter?

‘I don’t know that I’ll be goin’ no more. That new reverend’s an ’ellfire merchant. Looked me straight in the eye ’e did when he was thumpin’ the pulpit preachin’ about them as steal. Even the teensiest thing like a sliver of beef when they’m servin’ up fer those they work fer is a mortal sin, so ’e said. I went all ’ot and cold I did, ’cos didn’t I sneak some of your Seth’s best beef when I was dishing out after that uppity cook went and left, the night Seth’s pa and brothers got arrested fer smugglin’ and all them other things they got up to?’

‘Seth wouldn’t mind,’ Emma said, relieved that she was off the hook about going to church – for a while at least. Although she would have preferred it if Mrs Drew hadn’t brought Seth’s father and brothers into the conversation.

‘Anyways, what I’ve come fer – apart from admirin’ your swanky wedding photograph – is to ask what you’ll be needin’ me to do ’ere. Now that Hilltop has sold.’

‘It’s sold?’ Emma gasped.

‘Didn’t I just say, Emma Le Goff? Oh, beg your pardon, Emma Jago now.’ Mrs Drew did a mock-curtsey. ‘I don’t suppose Seth ’as ’ad time to tell you yet. I was over there givin’ the breakfast room a thorough clean just now and the folks as ’e was showin’ round said they’d take it. Solicitor is comin’ this afternoon with papers and that. And that’s not all. I can’t quite believe it yet, though I’m goin’ to do my best!’ Mrs Drew chuckled. ‘Your Seth’s only gone and said I can live in Shingle Cottage now you won’t be needing it no more – and rent free as long as I do a bit of cleanin’ up here fer you, now I won’t be doin’ fer ’im at Hilltop any more.’

‘Yes, he told me he’d do that when the time came.’ He also told me he was going to the bank she thought. He hadn’t said anything about showing anyone around Hilltop.

‘And only just! Don’t think I ’aven’t noticed Seth ’asn’t been coming back ’ome night times. Stoppin’ with you, no doubt.’

‘I only moved in here after our marriage,’ Emma said.

Gosh, how silkily the word marriage slipped off her tongue – she almost believed it herself.

‘I didn’t say he were stoppin’ ’ere with you, did I? Got more’n one place ’e could stop, ’asn’t ’e? Shingle Cottage where you’ve been livin’ bein’ one of ’em. Don’t you tell me that ain’t true, lovie, or the Lord’ll strike you down dead fer lyin’.’

‘Once or twice,’ Emma blushed. ‘He might have stopped the night once or twice.’

Mrs Drew made a noise like a snorting horse – once or twice, indeed, that snort said. ‘Most nights, more like,’ she said. ‘An’ I ain’t moralisin’ you ’bout the sharin’ a bed neither, ’cos God only knows you and Seth, both, were in sore need of a bit of lovin’. But all in all, it’s just as well you’ve gone and tied the knot. You know, just in case little ’uns come along.’

Emma decided it was time to change the subject. ‘I wonder who the new owners of Hilltop are?’

‘Incomers. From Bath. I ’eard ’em tellin’ Seth so. Goin’ to be takin’ over Deller’s Café on the Torbay Road. Not that I was eavesdroppin’, mind.’

‘Not much!’ Emma laughed. ‘What else did you not eavesdrop on?’

‘Ere, watch it, miss, or I wouldn’t be beyond givin’ you a clip around the ear fer your cheek seein’ as your ma ain’t ’ere to do it fer me.’

‘Mama never laid a finger on me,’ Emma said.

‘I know she didn’t. And it were only my little joke – a bad one an’ all. Anyways, I ’eard there’s goin’ to be a three-piece band, whatever that is when it’s at ’ome.’

‘It’s a music turn. Usually a piano and a violin and a double bass. They play discreetly in the background while people nibble at dainty cakes.’

There’d been a three-piece band playing at Nase Head House, where she’d worked for Rupert Smythe not so long ago, on the night a solicitor called to say that Carter Jago had been hanged. The night she’d stormed out, to face an unknown future, in nothing but a fancy dance frock bought for her by Rupert Smythe, who’d bought her so many things in his grooming of her, in his determination to make her the second Mrs Smythe.

‘Do they now? An’ I ’spect they’d like your fancy French tarts better’n dainty cakes, don’t you?’

‘Now there’s an idea! A ready-made new outlet for my cooking, perhaps.’ So much was happening so fast for Emma these days she was dizzy with the thought of it all at times.

‘Well, knowin’ you, you’ll make it so. And if you ask me, it’s about time things turned good fer you, lovie. God only knows you’ve ’ad an ’ard enough time of things up until now.’

Emma didn’t want to think back over those hard times any more than she had to. ‘Come on, Mrs Drew,’ she said. ‘I’ll show you over the house, and what I’d like you to do.’

‘An’ you’ll work me to the bone doin’ it all, no doubt,’ Mrs Drew said, even though she sounded as though she wouldn’t mind that at all. ‘All them carved banisters going up the stairs I saw just now in the ’all when I came in. They’ll be needing polishin’ on a regular basis, and them tiles on the floor in the ’all will need washin’ every day. Drawin’ room, kitchen, dinin’ room. So many rooms. You’ve even got a room jus’ fer ’aving breakfast in, so Seth said. Six bedrooms an ’all you’ve got. You and Seth will ’ave to be at it—’

‘Mrs Drew!’ Emma stopped her.

‘I know, I know. Oversteppin’ me mark, ain’t I? But I’m gladder than a mayfly that’s ’ad its day in the sun that you’ve got it all after everythin’ you’ve been through. Like I said, things ’ave got to get better for you, ’aven’t they, lovie?’

Yes, Emma thought, as she gave Mrs Drew a guided tour of Mulberry House, things just had to get better from now on.

Seth parked the Wolseley on the esplanade in Paignton. It had been a nerve-wracking journey because the mechanic from Evans Garage had only given him a ten-minute lesson on how to drive the car. He’d stalled a couple of times driving up to Hilltop to meet the estate agent and the people who wanted to buy it. What a surprise that had been – how quickly they’d agreed to buy. He hoped Emma would be pleased with that news. She hated the house, and with good reason, after what his brother, Carter, had tried to do to her in the drawing room there.

Born with a silver spoon in his mouth, as the saying had it, Carter thought that to take any woman he wanted was his right, and against her will if needs be. But Carter had met his match in Emma, thank God, when she’d gone up to Hilltop looking for him – Seth. If Carter hadn’t swung for murdering the housemaid, Sophie Ellison, Seth knew that he himself would have swung for killing his brother, if Carter had harmed Emma.

Seth ran a hand over the shiny black wing of the car. It had been a race against time to drive the seven miles to Paignton afterwards for his next appointment. It would be easier driving back. Emma hadn’t seen the car yet and he couldn’t wait to surprise her with it. Take her for a drive somewhere. Up towards the moor, sit and hold hands and watch the sunset maybe. He’d bought two wool travelling rugs, so wrapped in those they’d be warm enough.

He’d go into the Esplanade Hotel on the other side of the green later. Probably for a brandy. He’d need it without a doubt. But first he had an appointment to keep. He had a wad of notes in his pocket. Would it be enough to pay Caroline Prentiss off? He hoped so. While Emma knew he’d been sweet on Caroline once, he hadn’t told her just how far that relationship had gone. Although he had a feeling Emma had suspected he hadn’t been a virgin the first time they’d made love.

‘Where,’ she’d said, her eyes glittering, her body burning beneath him, ‘did you learn to make a girl feel like this!’

And each time they made love it seemed to get better and better – for Emma as well as for himself, as she was always so happy to tell him.

Seth scurried on down the alley that ran beside the railway line. It smelled of urine and beer and coal smoke. A mix that made him want to retch. Once through the arch that led to the bandstand in the park, he could see Caroline waiting for him. Not for the first time, he wondered why, and how, he’d got involved with her – a widow, ten years his senior – in the first place. No, he knew the reasons. Caroline was attractive and, at the time, predatory, and he’d slipped into her bed easily enough when she’d invited him to, certain, at the time, that Emma was lost to him.

Caroline had her back to him, shoulders up to her ears almost. But he would have recognised her anywhere – her height, her almost white-blonde hair and the way she always wore it coiled at the back with a hat set at a jaunty angle. She was lovely to look at, no denying, but Seth definitely wasn’t looking any more. He quickened his step. Best get it over with.

The grass was damp under his feet, silencing his footfalls. ‘Caroline,’ he said softly, so as not to give her a shock at his sudden arrival.

She wheeled round.

And it was Seth who got the shock.

Caroline, always so well dressed, so well kept, seemed years older than when he’d last seen her. Her skin had a greyish hue, and her eyes were dark-rimmed and sunken in her face.

And she was holding a baby in a shawl. A baby with a very red face, as though it had been crying very recently. Seth gulped, tried to say something but the words vanished in his throat the way Pelosi’s delicious ice cream always did on the tongue. No wonder Caroline had suggested he meet her miles from where her parents lived, where she was unlikely to be recognised.

‘Quite a surprise, eh?’ Caroline said.

Seth nodded. So, it was true. She had had his baby. She’d said as much in her letter, which was why he was here at all, even though Seth hadn’t believed her.

‘No doubt, is there?’ Caroline said. ‘She’s got your hair.’

Caroline pulled the shawl away from the baby’s head before covering it again against the cold.

‘It’s a girl?’

‘Girls usually are “she”.’

Seth didn’t want to look at the child, but she’d opened her eyes now and seemed to be staring straight at him.

‘How old is she?’

‘Four months. She was born on July 16th. It’s taken me until now to get over the birth. I almost died having her. Thanks to you.’

‘If she is mine,’ Seth said. More than a few times during the months he’d been seeing Caroline he’d had a niggle of a feeling that he wasn’t the only one she’d been inviting into her bed. Caroline, of course, always denied it, when he’d broached the subject.

‘She is yours. Look at her hair, for goodness’ sake. Blacker than night it is. And, like I said, it nearly killed me having her.’

Seth pressed his lips together. That this child had hair the same colour as his without even a hint of wave in it, he couldn’t deny. But what to say? What to think?

‘Well?’ Caroline said, obviously irritated at his hesitation.

‘I wish you’d told me before,’ Seth said.

‘Before what?’

Before I bought a house for Emma and built her a bakery and let her give her heart to me the way I’d already given mine to her. But he couldn’t tell Caroline any of that, could he? And would he have wanted to commit to Caroline for the rest of his life, even for the baby’s sake?

‘Oh, I know,’ Caroline sneered. ‘Before it grew so bloody big it nearly burst my belly open, you’d have handed over some of your pa’s ill-gotten gains for an abortion in some back alley and killed me that way.’

‘I’ve got the money you asked for,’ Seth said quickly. The sooner he could bring this conversation, this encounter, to an end and get back to Emma, the better it would be. His fingers trembled as he took the notes from his inside pocket. He’d promised he’d never lie to Emma and that it would be truth between them always, but would this finish it for them before it had even started? ‘And I’ll send you more if you tell me where to send it.’

‘Oh, I will – you can be sure of that. I went to Plymouth as a lady’s companion. It turned out to be a good cover in the end. The soft old bugger lost a daughter of her own, so she’s been only too happy to have her about the place.’ Caroline jiggled the baby – rather roughly, Seth thought – in her arms. ‘And I’m going back to Plymouth on the next train.’ Caroline snatched the money from Seth’s hand. ‘I knew you wouldn’t part with your money without evidence. This is to pay the doctor who delivered her. And for the nursing care afterwards.’

Seth let Caroline’s words wash over him. The baby – his baby – was smiling at him and he was smitten. He didn’t have the first clue about babies, but wasn’t this baby a bit small for four months old?

‘Four months old, you say?’

‘Give or take a week or two.’

‘Is she well? She’s so tiny.’

‘I’m fine-boned myself, if you remember.’ Caroline took one arm away from holding the baby and ran a hand down over a hip.

‘What’s her name?’ Seth asked, wanting an end to this encounter, and quickly.

Caroline shrugged. ‘I don’t call her anything.’

‘But you’ve registered her birth? You must have.’

‘Of course I did. It’s an offence not to. I asked the registrar what his wife’s name was and he said Rose, so I called her that. It’ll do.’

‘Rose,’ Seth said, reaching out with a finger to touch the baby’s cheek.

‘Very touching,’ Caroline said. ‘I can see you’ll honour your obligations. I don’t want to be a companion forever and it’s getting harder and harder by the day with her to care for, too.’ Once again, Caroline jiggled Rose roughly in her arms – and it was as though she couldn’t bear to say the child’s name. ‘So, once I’ve taken this money back to Plymouth, when are you going to do right by me? You’re a rich man now, Seth, so I’ve heard. Once we’re married, a nanny can do the caring.’

‘Married?’

‘Yes. As in you and me saying vows.’ Caroline smiled then, for the first time, at Seth. She pursed her lips, then poked the tip of her tongue through them. ‘You can’t have forgotten how good we were together?’

No, Seth hadn’t forgotten the physical aspect of his relationship with Caroline, but his heart had never been hers and never would be. And now there was Rose to consider. He could see Caroline didn’t have a scrap of love for her daughter – his daughter, too – but what could he do about it?

‘I’ll support Rose financially for as long as she needs support. But we aren’t going to be exchanging vows, Caroline,’ Seth said. ‘We can’t. Because, you see, I’m already married.’

Not the truth, but Caroline wasn’t to know that. Not ever. All the colour leached from her face and Seth thought she might faint. But then she turned puce with rage. ‘You’ll be sorry,’ she hissed. ‘Just see if you aren’t.’