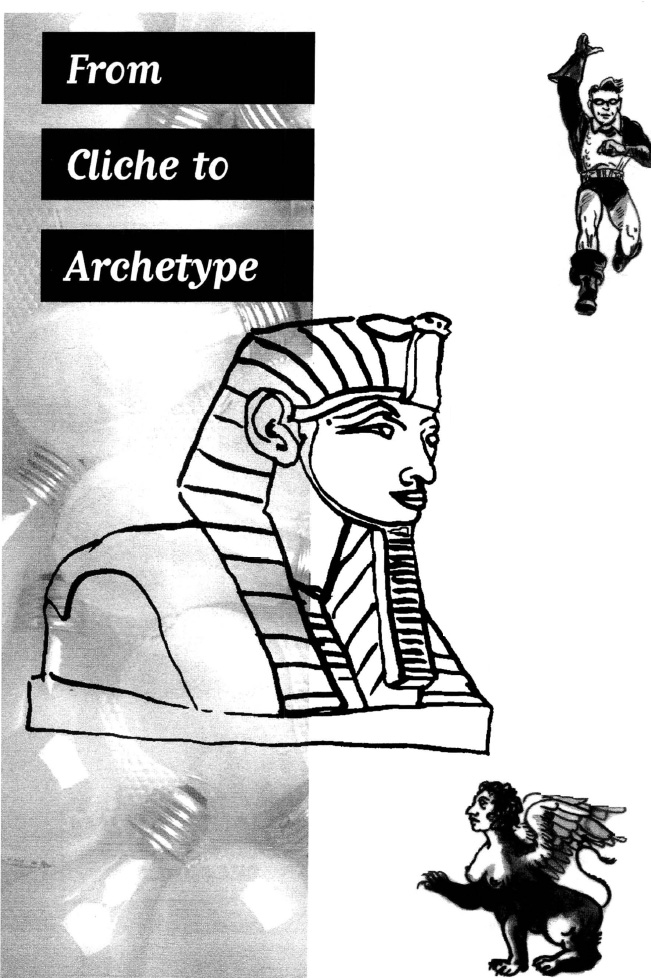

fter doing a lot of mosaic writing, McLuhan turned around and published what seems to be set up like a mini-encyclopedia—From Cliché to Archetype (1970). But it turns out to be a put-on! It’s just as much a mosaic as his other books, and when you stop to think about it, he packs so much into those books that they are like encyclopedias too. It’s all a trick to get us thinking about the ideas packed into the title—clichés and archetypes—what they are and how they interact.

fter doing a lot of mosaic writing, McLuhan turned around and published what seems to be set up like a mini-encyclopedia—From Cliché to Archetype (1970). But it turns out to be a put-on! It’s just as much a mosaic as his other books, and when you stop to think about it, he packs so much into those books that they are like encyclopedias too. It’s all a trick to get us thinking about the ideas packed into the title—clichés and archetypes—what they are and how they interact.

Most readers will recognize cliché as meaning a worn-out expression, but what is an archetype? McLuhan explores the various meanings of archetype, but it is useful for us to start with a general, basic definition:

In literature an archetype is a symbol or image (person, place, or thing) that we recognize because we meet the type repeatedly:

ut we meet clichés repeatedly too. It’s because they are repeated so often that they are clichés. So we see already why McLuhan emphasizes the connection between cliché and archetype.

ut we meet clichés repeatedly too. It’s because they are repeated so often that they are clichés. So we see already why McLuhan emphasizes the connection between cliché and archetype.

An archetype is a category you can add to (the more you have read, the more names you can add to those of Beowulf and Batman); a cliché is not a category, and you cannot add to it. But you can change it, and we will see what McLuhan has to say about how this is done in the hands of artists.

We saw how McLuhan stretched the sense of “medium”; he does the same with “cliché”, defining it at different times as:

an extension,

an extension,

a probe,

a probe,

a means of retrieving the past.

a means of retrieving the past.

These are echoes of important notions from McLuhan’s other writings. They show us how central the cliché is in his analysis.

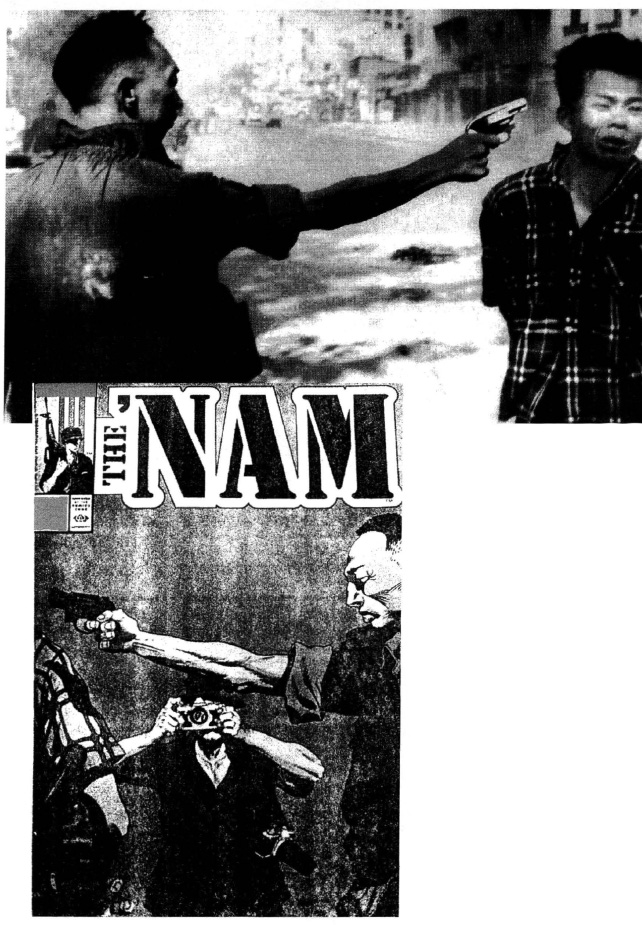

McLuhan goes so far as to say that our perceptions are clichés (because our physical senses are a closed system), that all communications media are clichés (because they extend our physical senses), and that art is cliché (because it retrieves older clichés).

he simplest definition of cliché for McLuhan is that of a probe. This may sound like a paradox (especially if we go back to the definition of cliché as a worn-out expression), and McLuhan admits that this is so. BUT, what happens is that artists sharpen clichés into probes, into new forms that jolt us into awareness. The familiar, even the worn-out, becomes new.

he simplest definition of cliché for McLuhan is that of a probe. This may sound like a paradox (especially if we go back to the definition of cliché as a worn-out expression), and McLuhan admits that this is so. BUT, what happens is that artists sharpen clichés into probes, into new forms that jolt us into awareness. The familiar, even the worn-out, becomes new.

s usual, one of McLuhan’s favorites to illustrate this point is James Joyce, who wakes up language (creates new clichés) by putting it to sleep (destroying old clichés). We hear the echo of

s usual, one of McLuhan’s favorites to illustrate this point is James Joyce, who wakes up language (creates new clichés) by putting it to sleep (destroying old clichés). We hear the echo of

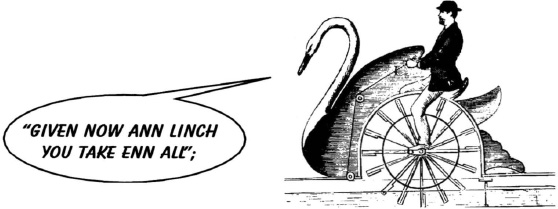

“give an inch and take a mile”

when Joyce writes

we catch the clichés

“skin of his teeth”

and

“earned his bread”

transformed into probes that call up the myth of King Cadmus when Joyce writes “He dug in and dug out by the skill of his tilth for himself and all belonging to him and he sweated his crew beneath his auspice and he urned his dread”.

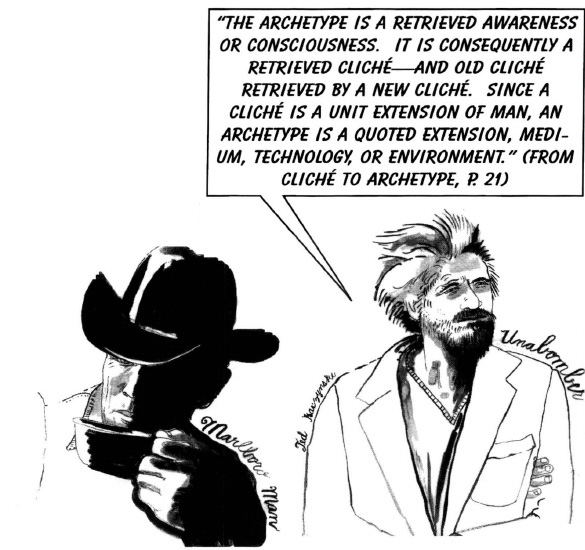

Archetypes both interact and contrast with clichés. McLuhan defines the archetype as a retrieved awareness or new consciousness. This happens when the artist probes an archetype with an old cliché, as in the examples from James Joyce above. Sooner or later, the probe itself turns into a cliché. McLuhan views all form, whether in language, visual arts, music, etc., as a reversing of archetype into cliché. But cliché also reverses into archetype.

Let’s give McLuhan himself the last word on the subject: