cLuhan glibly dismissed many of his critics in academe as hacks, noting that because they had “been asleep for 500 years,” they probably didn’t like the idea of anybody coming along and stirring things up. But his critics in the popular media were just as hard-hitting.

cLuhan glibly dismissed many of his critics in academe as hacks, noting that because they had “been asleep for 500 years,” they probably didn’t like the idea of anybody coming along and stirring things up. But his critics in the popular media were just as hard-hitting.

Even Wired was less than complimentary of their patron saint, charging that by the time he died, McLuhan was “known in the popular press as an eccentric intellectual whose day in the media spotlight had come and gone”.

n October 1979, McLuhan suffered a massive stroke which left him unable to speak. Fifteen months later, in the early morning of New Year’s Eve 1980, he died peacefully in his sleep. The inscription on his gravestone, is in digital-analogue typeface and reads:

n October 1979, McLuhan suffered a massive stroke which left him unable to speak. Fifteen months later, in the early morning of New Year’s Eve 1980, he died peacefully in his sleep. The inscription on his gravestone, is in digital-analogue typeface and reads:

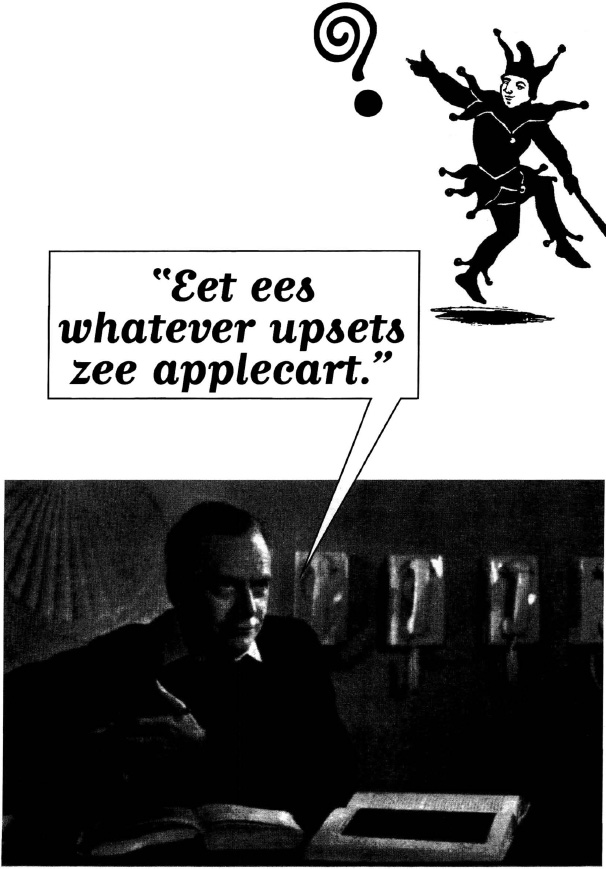

nd what, to McLuhan, was truth

nd what, to McLuhan, was truth

He liked to answer that question with a quote from Agatha Christie’s criminal sleuth, Hercule Poirot:

In that regard, McLuhan was a very, very free man, indeed!

If we had to put McLuhan into one sentence, it could be this:

It’s a ridiculous question, but McLuhan wouldn’t object. The only reason to ask it is so that we will ASK OURSELVES MORE QUESTIONS.

e can’t know WHAT we don’t notice unless we ask ourselves WHY we don’t notice more about our world. And this is where McLuhan’s teachings about media and environments come in. McLuhan doesn’t care if we ask different questions and come up with different answers than he did, as long as we discover something about our world and what is happening to it.

e can’t know WHAT we don’t notice unless we ask ourselves WHY we don’t notice more about our world. And this is where McLuhan’s teachings about media and environments come in. McLuhan doesn’t care if we ask different questions and come up with different answers than he did, as long as we discover something about our world and what is happening to it.