10. I Got Rhythm

I got rhythm, I got tempo, I got meter

There is a strong link between rhythm and vegetarians. I’m not talking about the relative dancing abilities of vegetarians and omnivores here, as I have observed examples of excellent and execrable hoofing from both camps. I mean that there is a strong link between the way we use the words “vegetarian” and “rhythm.”

When we say “Kay is a vegetarian” we don’t necessarily mean that she eats only vegetables. Lots of vegetarians also eat a wide range of things which are not vegetables, such as eggs, legumes, cheese, and many other foods packed with revolting vitamins. We are using “vegetarian” as a convenient label.

Any piece of music consists of a stream of sounds spread over a certain amount of time, and we use the word rhythm to describe how we organize the timing and emphasis of those sounds. But we are using the word as a convenient label. In fact, when we talk of rhythm in this way we are really referring to three things: tempo, meter and rhythm.

The tempo of a piece of music is its pulse rate—how often you would tap your foot to it.

The meter is how often you would emphasize one of the foot taps. For example, if you are listening to a waltz you will emphasize the first tap of groups of three—one, two, three, one, two, three. If you are listening to rock music (or most other Western music), you will stress the first beat of groups of four—one, two, three, four, one, two, three, four.

The rhythm is the pattern of long and short notes being used at any particular time. For example, the beginning of Beethoven’s Fifth Symphony (Da Da Da Daah) has a rhythm of three short notes followed by a longer one. You can play it as quickly or slowly as you like, but you won’t change the rhythm—it will always be three short followed by one long.

Having explained all that, I will now return to the normal, conversational use of the word “rhythm” for the rest of my discussion.

When I was putting this book together I considered all sorts of methods for drawing pictures to explain how rhythms work, but eventually I realized that the clearest and simplest pictures of rhythms were the ones we use in standard written music. The Western system of written music is a diagram which tells musicians which notes to play, when each note should start and stop, and which ones to emphasize. We can use this system for our discussion of rhythm—but don’t panic, I am not going to expect you to be able to read music.

Actually, learning to read music is a pain in the neck—and don’t let anyone tell you otherwise. It’s very interesting for approximately the first ten minutes, when you’re learning what it’s all about. After that there is a long struggle before you can get your fingers to obey the instructions on the page and produce music. This long struggle is similar to the one involved in learning a language, and the rewards are just as great, but in this chapter we are only going to cover those interesting first ten minutes.

The development of written music

The trouble with ancient history is that, as far as I can tell, the vast majority of it took place a hell of a long time ago. This means that it’s very difficult to know when written music was first attempted. There is some evidence of ancient written music of various levels of sophistication in China, Syria and ancient Greece. One of the earliest complete compositions we have discovered so far was inscribed on a tomb about 2,000 years ago. This song, known as the Seikilos Epitaph, is written in an ancient Greek musical notation which tells you which note to sing for each word and how long each note should be. The lyrics of the song encourage us, in the true rock and roll tradition, to shine while we live because life is short.

The written music system we use for Western music dates back to the time when monks and nuns were much more a feature of the national music scene than they are today (although there were also professional musicians around). In the early days, the music would be thought up by a talented musician, monk or nun, and taught directly to his or her friends by singing or playing. Eventually, however, the music became more complicated and composers realized that writing it down would be a handy way of teaching and recording it. Also, by about A.D. 750 the Christian church was beginning to insist that masses should be sung using various standardized rules. For these reasons there was a lot of interest in writing music down. Some early composers used to draw pictures of how the music went up and down but this wasn’t very accurate. By about A.D. 800 there was general agreement on the following rules.

- You need to use different sorts of dots or shapes for different lengths of note.

- The dots should be drawn one after another, reading from left to right.

- The dots should be drawn on a “ladder” to show how high or low the notes are.

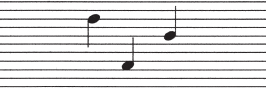

Writing down music involved giving names to the notes and so they drew their “ladder” and named the notes from A to G. The earliest ladder had eleven lines, like this:

One early idea was to write the notes on an eleven-line “ladder,” or “stave,” like this, but as you can see, it’s very difficult to identify quickly exactly which line or space the notes are on.

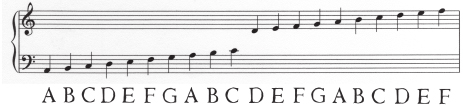

This ladder (or stave as it is called) had so many levels that it was very difficult to read, so composers split it into two sections, low (or bass) and high (or treble) like this:

The modern stave split into two sections (treble and bass) for easy reading. (Note that middle C is stuck in the middle between the two staves.) The two symbols on the left are just there to identify the treble and the bass sections of the stave because some instruments don’t need this enormous range of notes and only use the treble (e.g., violin) or bass (e.g., cello) part for their written music. The symbols are called the treble clef and the bass clef.

Splitting the stave into two parts leaves one note, a C, between the two sections. This is the famous “middle C” you have heard about—it’s the middle note on a piano as well. Middle C has no special musical significance—it’s just a convenient reference point. Musicians, for example, will say things like “I can’t sing this twaddle—my singing range is only up to the G above middle C. Who do you think I am? Freddy bloody Mercury?”

In the illustration below you can see the first lines of two of the songs we have been using for reference throughout this book. I have only used the treble part of the stave because—for these tunes—I don’t need the big range in pitch which both staves would give me.

The first lines of “Baa Baa Black Sheep” and “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow.”

We will look at how rhythms and notes of different length are noted down in a minute, but first let’s look at how the vertical position of the notes tells us how the pitch of a tune goes up and down. If you sing the songs while looking at the written notes you will notice that the notes go up and down the ladder, just as your voice does as the songs progress. I have started both songs on the same note so that you can compare them easily. If you hum these songs you will notice that both of them begin with notes of the same pitch and then there is a big leap up to “black” or a small jump up to “he’s,” depending on which song you are humming. In every case the musical jump you hear is accurately identified by the vertical position of the notes on the written stave. Remember, as I said in chapter 2 , you don’t need to start on the correct note (“C” in this case) to sing well—unless you are being accompanied on an instrument. The most important thing is the size of the jumps in the tune. It takes a lot of training to be able to look at a new tune and sing the jumps correctly just by reading the music—but the exact information is all there.

Key signatures

In the last chapter we discussed the fact that different keys involve different notes. For example, the key of A major includes the notes A, B, C#, D, E, F# and G#. If a composer is writing in this key he doesn’t want to be bothered with putting a sharp sign in front of every individual F#, C# and G# so he writes a general instruction at the beginning of every line of the music—called the key signature. The key signature of A major, with the instruction to play all the Fs, Cs and Gs as F#, C# and G#, looks like this:

The key signature of the key of A major. The three sharp signs are written on the lines which represent the notes F, C and G (reading left to right). This is a general instruction which means “Every F, C and G should be played as F#, C# and G#.”

Writing down rhythms

Different lengths of note

Our two songs involve notes of various lengths and we use different symbols to indicate how long each note is compared to the others. The note symbols and their names were agreed upon centuries ago and are listed below. As you can see, the notes get shorter in a very organized way: we start with a very long note (or “breve”) and divide it in half to get a half note (or semibreve), then continue dividing the length of the notes in half to get shorter and shorter notes. Nowadays we also talk about “whole notes” and “quarter notes” and, just to confuse everyone, it has come to be generally accepted that the semibreve, not the breve, should be counted as a whole note—as you can see in the illustration.

| Symbol | Name |

|---|---|

|

Breve |

|

Semibreve (whole note) |

|

Minim (half note) |

|

Crotchet (quarter note) |

|

Quaver (eighth note) |

|

Semiquaver (sixteenth note) |

|

Demisemiquaver |

|

Hemidemisemiquaver (no, I am not joking) |

A list of the different symbols for notes of different lengths. Each note is twice as long as the one below it.

If this “halving” system was all we had to describe the length of notes, then our music would be rather dull rhythmically, so we have a couple of additions to give us more flexibility:

1. A dot written immediately after a note means “this note should sound one and a half times as long as normal” (you can see such a dot after the note for “fe” in “fellow”). A double dot after the note is much less common but means “this note should sound for one and three quarters as long as usual.”

2. You can write a small “3” above a group of three notes to indicate that “these three notes should take up the same amount of time as two notes would normally.” This is a fairly common device and you will have heard it in action many times. Rather less common is the writing of “5” above a group of five notes, or any other similar combination. In every case the message is, “this group of notes should be squeezed into the amount of time allowed for a group of this size minus one,” i.e., 5 should only take as long as 4 usually would, 13 should take as long as 12 usually would, etc.

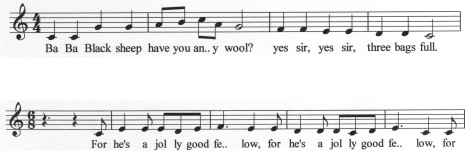

Sometimes notes are written as individuals (this is common for singing) but more often the shorter notes are joined to others to make little groups, as you can see in the songs. This joining together doesn’t affect the length of the note—it just helps the musician to read the music.

The shorter notes are usually joined together by their “tails” rather than written individually. The two quavers drawn above (on the left) each have a single tail and would be joined by a single straight line (as on the right of the illustration). Semiquavers have two tails, so they are joined by two lines, and so on.

Looking back to the notes for “Baa Baa Black Sheep,” and referring to the list above, you can see that the notes for “have” and “you” are half as long as those for “black” and “sheep,” which are, in turn, half as long as the note for “wool.” You might have thought that the notes you were singing were just randomly longer or shorter—but you are in fact singing notes whose lengths are closely related to each other.

Stress or emphasis: the use of bar lines

“Baa Baa Black Sheep” is a simple song but it would be simple to the point of dullness if all the notes were the same length and they all had equal emphasis. You will notice that there are vertical lines drawn on the stave at a regular distance apart, which do not have any note or sound associated with them. These are called bar lines. The distance between two bar lines (where we write the notes) is technically called a measure—but everyone I’ve ever met calls it a bar so that’s the word I’ll use.

One of the conventions of written music is that the first note after a bar line is given extra emphasis, or stress. When you sing “Baa Baa Black Sheep” you stress the first “Baa,” the word “have” and the first “yes.” In the written version of the music, these words appear just after a bar line. If you haven’t noticed that you emphasize in this way, try singing the song with deliberate stress on “sheep” and “any.” It all sounds a bit Monty Python, doesn’t it? Now sing it again with the emphasis where it should be—on “Baa” and “have.” You may now be over-emphasizing but the stress is in the right place—just after the bar line—so it sounds OK.

Now, without looking at the written music, sing the first line of “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow” a couple of times. It’s only six words, but it involves eight notes: For, he’s, a, jo, lly, good, fe, llow. Imagine that you are singing the song in a funny/dramatic way to a friend. For extra effect you have brought a cymbal with you. The noise from a cymbal lasts a long time so you will only hit it once in every line of the song. Sing the song aloud a couple of times and imagine which of the eight sounds you would choose to hit the cymbal on. Will it be “For,” “he’s,” “a,” “jo,” “lly,” “good,” “fe” or “llow?” Using my mysterious powers, I can confidently tell you that you will have chosen to make your big crashing noise on either “he’s” or “fe.” Now have a look at the music—yes, “he’s” and “fe” are both immediately after a bar line.

In many cases we would automatically choose the first note of the song as one of the notes to be emphasized. In “Baa Baa Black Sheep,” for example, you would have clashed your cymbal on the first word, “Baa,” or the word “have.” In the case of “For he’s…,” however, we would not choose the first note “For” because it does not come immediately after a bar line—the song does not start at the beginning of a bar. Just in front of the word “For” there is what musicians call a “rest,” a mark (in this case two marks) indicating that the first part of the bar is silent. This may sound a little weird—starting a tune with a silence—but we do it to get all the stresses in the song or tune to fall in the correct place, just after the bar lines. Here are a few examples of songs with the accented syllables printed in bold type.

Tunes which start at the beginning of a bar:

- Twinkle, Twinkle Little Star (Twinkle Twinkle Little Star…)

- Frère Jacques (Frère Jacques Frère Jacques dormez vous…)

- London Bridge is Falling Down (London Bridge is…)

Tunes which don’t start at the beginning of a bar:

- When the Saints Come Marching In (Oh, when the Saints…)

- On Top of Old Smoky (On top of Old Smoky…)

- Auld Lang Syne (Should old acquaintance be forgot…)

- Greensleeves (Alas my love…)

If you ever see these tunes written down you will see that the bar lines come immediately before the syllables I have highlighted.

Dividing up the bar—time signatures

You will notice that our two tunes begin with numbers which look like fractions. These numbers (called the time signature) tell the musician how many “beats” there are to each bar and, roughly, how long those beats are.

How many beats to the bar? The upper number in the time signature

The upper number in a time signature is the most important one—it gives you the meter of the music, that is, how many beats there are to the bar. Let’s take the two most common values for this number: 3 or 4 (4 is by far the most common).

If the time signature has an upper number of 3 then the overall pulse of the music will be: one two three, one two three—like a waltz. There doesn’t have to be a note played for every one of the three beats, and the tune may sometimes involve more than one note per beat; in any case your mind will retain this sense of a pattern of three beats.

Similarly, if the music has a 4 as the top number of the time signature, the music retains an overall “one two three four, one two three four” rhythmic pulse no matter how many notes are played during each pulse. Most people who have not had any musical training find this difficult to understand. When asked to clap out the rhythmic beat of a familiar tune they tend to clap once per note like this:

| Baa | baa | black | sheep | have | you | an - | y | wool? |

| clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap |

In this case you get four evenly spaced claps followed by five faster ones.

A musician, asked to clap out the basic rhythm, would do it this way:

| Baa | baa | black | sheep | have you | an - y | wool? | |

| clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap |

Now we get eight equally spaced claps: the musician claps regularly even when there is more than one note per beat (“have you” and “any”), and keeps clapping at the same rate through long notes or silences (in this case there is a one-beat silence between the end of “wool” and the “yes” which follows it).

If we ask the musician to emphasize the note at the beginning of each bar we would get:

| Baa | baa | black | sheep | have you | an - y | wool? | |

| clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap |

This tells us that this music has four beats to the bar.

Asking the musician to do the same job for “America,” we would hear:

| My | coun | try, | ’tis | of | thee | sweet | land | |

| clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap |

Here we can see that the beats come in groups of three—so the upper number in the time signature will be a three.

The most common time signature (which covers the vast majority of pop music and most classics) divides the bar up into four beats—here is a slightly more complicated example than “Baa Baa Black Sheep”:

| Oh when the | Saints | Oh when the | Saints | |||

| clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap | clap |

Whatever the time signature, words (notes) sometimes occur between the beats (“Oh” and “the” from “When the Saints,” and “of” from “America”); sometimes notes last longer than one beat (“tis” and “Saints”); and sometimes a beat happens when there is no note (before “Oh”).

If the piece of music has three beats to the bar, then the first beat is the strong one and the other two are weaker (one two three, one two three). In the case of four beats to the bar, the first beat is the strongest but the third beat (the halfway point in the bar) is the next strongest. The second and fourth beats are both weak by comparison—so the stress in a four-beat-to-the-bar piece is: one two three four, one two three four.

Another case of splitting the bar in half occurs if there are six beats to the bar—which is common in Irish jigs. As you can see in the written example, “For He’s a Jolly Good Fellow” has six beats to the bar. To get the emphasis correct, this time signature is usually counted aloud in the following way: one two three two two three, one two three two two three. The second two (in italics in the middle of the bar) is stressed, but not quite as much as the one—for he’s a jolly good fellow.

Four beats to the bar is, as I mentioned, the most popular case in Western music of any sort and three beats (mostly waltzes), two beats (mostly marches) and six beats (mostly jigs) are used in most of the remaining cases—all other numbers are fairly rare. Modern jazz and modern classical music sometimes make a point of using five, seven, eleven, or more beats to the bar (sometimes just to be clever and unusual), but there are only a few really popular successes:

- five beats to the bar—“Take 5” by the Dave Brubeck Quartet and “Mars” from The Planets by Gustav Holst;

- seven beats to the bar—“Money” from Dark Side of the Moon by Pink Floyd and various bits of The Rite of Spring by Igor Stravinsky (which also contains many other unusual rhythms);

- nine beats to the bar—used in a particular type of Irish jig, called a slip jig, which divides the bar up into three sets of three beats (one two three, two two three, two two three).

Syncopation

Syncopation is a method of adding an extra layer of interest to music by deliberately emphasizing beats which would normally be unimportant. There are some types of music which deliberately avoid stressing the first beat of the bar in order to give the music a particular feel. Some rock and pop songs keep the “one two three four” emphasis for the tune but deliberately emphasize beats two and four with the bass guitar and drums, a technique known as “back beat” which was very popular with the Beatles (e.g., “Can’t Buy Me Love”). Reggae music takes this idea even further by having the first beat of the bar left almost silent by the rhythm section of the band. In general, the drummer and bass guitar player in a reggae band both emphasize beat number 3 and the rhythm guitarist plays beats 2 and 4.

Back beat, rock and reggae use specific types of syncopation which form part of their identity, but syncopation is used to some extent in nearly all forms of music. You can even syncopate “Baa Baa Black Sheep” to add interest to your performance: “Baa Baa Black Sheep Have You Any Wool…”

Syncopation doesn’t even need to involve a full beat of the music. You can emphasize just a part of a beat—“Have you any wool?” Wherever you come across it, syncopation makes the music sound less predictable and more sophisticated.

What length are the beats? The lower number of the time signature

The lower number of the time signature is always a 2, 4, 8, 16 or 32. Of these, 4 is by far the most common and, really, could be used in all cases. The reason for this is that, although the choice of lower number changes how the music looks on the printed page, it doesn’t have any real effect on how the music sounds. This odd fact needs some explanation—so I’d better get on with it.

I am going to use the term “whole note” rather than “semibreve” in the following discussion to keep things as clear as possible.

When a composer writes a “3” over an “8” as the time signature, she is saying that each bar will have three beats, each of which is one eighth of a whole note long—so “3” over “8” simply means “three eighths of the length of a whole note per bar, please.” Similarly, 5 over 4 means that each bar will contain five beats which are all one quarter of a whole note long (“five quarters of the length of a whole note per bar, please”).

The problem is that no one has ever said how long a whole note is. In the most common time signature (4 over 4), each bar is one whole note long (four quarters)—but if you pick twenty different pieces of music and measure how long the bars are with a stopwatch you will have twenty different results. Although no one knows how long a whole note is, we know the approximate range involved—a whole note (equal to a bar of 4/4 time) will generally be shorter than six seconds but longer than one second. This is, of course, an enormous range—so musicians need more information than just the time signature if they are to play the music as the composer intended.

Musicians get a bit of help from a word printed above the beginning of the music which tells you (usually in Italian or German) how fast the music should be played—“presto” means fast and “adagio” means slow. But these are, of course, rather vague terms—two different performers might differ in speed by 50 percent or more.

In an attempt to minimize vagueness, composers often put metronome marks next to the speed-indicating word. They will, for example, draw a note of a certain length (e.g.,  ) followed by an “=” sign followed by a number (e.g., 120). The number tells the musician how many of that type of note would last for one minute, so “

) followed by an “=” sign followed by a number (e.g., 120). The number tells the musician how many of that type of note would last for one minute, so “ = 120” means that you could fit 120 of these eighth notes into one minute—or that each

= 120” means that you could fit 120 of these eighth notes into one minute—or that each  note lasts for half a second. (A metronome is just a device which you set to tick as slowly or as quickly as you want it to—in this case you would, of course, set it to tick 120 times per minute and then play along in time with the ticks.)

note lasts for half a second. (A metronome is just a device which you set to tick as slowly or as quickly as you want it to—in this case you would, of course, set it to tick 120 times per minute and then play along in time with the ticks.)

The use of metronome marks sounds logical until you find out that most professional musicians don’t take much notice of them—they just play as fast or slowly as they want to. For example, I have a couple of recordings of the famous guitar concerto by Rodrigo in front of me (the Concierto de Aranjuez) and the CD boxes tell me that John Williams plays the romantic second movement in just under ten minutes but Pepe Romero completes the same piece in just over twelve minutes (that’s a 20 percent difference, and it has nothing to do with how well they both play their instruments; Pepe just likes the extra romance of playing it more slowly). The piece has a metronome marking at the beginning but also includes vague instructions to speed up and slow down at various points—so there is no “correct” completion time. It is also well known that many composers cannot decide on the correct number for the metronome mark and, if they have been recorded, often go considerably faster or slower than their own instructions indicate.

So there we have it—the bottom number of the time signature gives us little or no information about how the music sounds. You could, for example, write a piece in 3 over 8 and mark it “slow” or write it in 3 over 4 and mark it “fast”—the music would sound the same. In fact, the music in 3 over 4 might be played faster than the music in 3 over 8 because “fast” and “slow” are such vague terms. No matter how well trained you are you cannot tell whether the modern jazz piece you are listening to is in 3/4 or 3/8 (or tell the difference between 5/4 and 5/16). If you had to make a bet, your only guide would be that, traditionally, bigger numbers on the bottom of the time signature are usually associated with faster music. For example, a romantic Viennese waltz will almost certainly be written with a time signature of 3/4 rather than 3/8, 3/16 or 3/2. Similarly, an Irish jig will generally be written in 6/8 rather than 6/4 or 6/16.

This quick guide to how written music works can be reduced down to five points.

• The vertical position of the notes tells you the size of the jumps in the tune.

• Notes of different lengths have different symbols.

• Notes which appear immediately after the bar line are (usually) emphasized or stressed.

• The top number of the time signature tells you how many beats to the bar.

• The length of the beats is given approximately by the lower number of the time signature together with a word indicating the speed of the piece. Sometimes this speed information is given more accurately in the form of a metronome mark.

Dancing and rhythm

If we go back to my point that rhythm can be divided up into rhythm, tempo and meter, it may come as a surprise that rhythm is the least important of these three components where dancing is concerned. The lengths of the different notes in the music are far less important to a dancer than tempo and meter. The tempo of the music tells you how fast to dance and the meter tells you what type of dancing you are involved in. The vast majority of Western modern dance music is in a meter of four beats to the bar with a simple 1, 2, 3, 4 count and so the only important variable is the tempo.

There is a widely held misconception that your heart rate tries to match the pulse rate of the music you are listening to. This belief probably arose because the range of pulse rates for music and human beings is similar. The tempo of music is usually between 40 and 160 beats per minute (bpm), and human pulse rates range from about 60 for a relaxed person with a slower than average heart, up to above 150 bpm for a healthy young adult dancing his socks off.

If you are a healthy young adult dancing in a club, the music will have a tempo between 90 and 140 bpm, and your heart will be batting along at a similar rate. But the exciting noise of the music is not what’s driving your heart rate up—it’s the dancing. The music will have an average beat rate of approximately 120 bpm because this is a sustainable, fun rate at which to be waggling your various bits about. You can move your body and limbs twice a second (120 bpm) for an hour or so without anything snapping off. Your heart will be racing along, faster than normal because you are consuming a lot of energy. Next time you are in a club, try taking the pulse of a friend who is dancing and comparing it to one who is slumped at the bar. The dancer will have a heart rate close to the pulse of the music, but the slumper’s heart will be much slower. But don’t forget—we slumpers need love too.

Of course, dancing is nothing new, and people have always enjoyed shaking their bits in the general direction of people they fancy. Dancing usually involves raising your heart rate and the waltz does this in two ways. The first reason for an increased pulse is the physical effort involved. A waltz has a tempo of approximately 100 bpm. This is a lower tempo than the 120 of the music found in the clubs today, probably because you have more work to do. Two people have to coordinate their movements and then steer themselves around the dance floor rather than merely hopping up and down in one spot. It’s also fairly certain that sweating like a pig used to be less fashionable than it presently is.

The second heart rate accelerator of the waltz is the reason why it was almost banned when it was first introduced into polite society—it was a method of actually getting your hands on the body of your beloved, or be-fancied. Even the torrid waltz, however, is not quite as “hands on” as a much earlier dance with a three-beat meter, the volta, which was a favorite of Queen Elizabeth I. The volta involves a lot of lifting and lowering of the woman, with plenty of opportunity for mutually enjoyable, accidental hand slippage. If enough of you readers vote in favor, we could try to get it reinstated as the biggest dance craze around, as it was in London in the late 1500s.

Rhythm and polyrhythm

If you are sitting and listening to music, rather than dancing, you have a much deeper appreciation of the subtleties of rhythm. Meter, rhythm and tempo all play their part in our enjoyment. Although our pulse rates do not link themselves to the tempo, we certainly find slower tempos more relaxing and faster ones more exciting. This tension is probably linked to our dislike of uncertainty, particularly our fear of not being able to cope with a situation. If the sounds we are hearing are moving at walking pace or slower, then there is no need for anxiety. If things are rushing along we might need to be prepared to run away or protect ourselves.

One good way of getting a lot of emotion out of a piece of music is through a technique called rubato. The word means “robbed.” The musician steals a bit of time off a couple of notes in order to make the note before or after them last a little longer. Instead of hearing the notes with a steady rhythm, “Daa, Daa, Daa, Daa, Daa, Daa,” we get the effect of a rush up to a longer note, “Daa, Daa, Daa, Da-Da-Daaaa,” which adds drama and romance to the music.

Changes of meter are a good way of keeping our interest levels high, and unusual meters such as seven beats to the bar also keep us interested because they sound unsettled or incomplete. But a lot of Western music is not very rhythmically adventurous or sophisticated. The music tends to concentrate on four or three beats to the bar with simple, regular sub-divisions of these beats. African and Asian musical traditions and several others often employ greater rhythmic complexity, including the use of polyrhythms.

Polyrhythm involves playing two or more non-collaborative rhythms at once. To explain what this means, let’s take the example of you and me tapping out rhythms on your dining-room table. If we both tap together in groups of four, we are just tapping the same rhythm. If I tap eight times to every four of yours, then our rhythms will collaborate—we will be hitting the table at the same time at regular, frequent intervals, and every extra tap of mine will fit exactly into the gaps between yours. If, on the other hand, I tap the table five times for every twelve of yours, then our taps will not coincide very often, and most of the time my taps will not be synchronized with yours in any obvious way. The two rhythms are no longer collaborating. We are tapping polyrhythmically.

The idea of polyrhythms is not completely new to Western music. Mozart used a pulsing accompaniment based on threes against a tune based on twos in the second movement of his Piano Concerto No. 21 (this piece is nowadays known as “Elvira Madigan” because it was used in a film of that name). More recently, some jazz and rock bands have used polyrhythms and I think that they will gradually become more commonplace. This will be useful for people like me, because when people tell me I’m dancing really badly, I can just claim to be dancing to the other half of the polyrhythm.