11. Making Music

The myth of musicality

For some reason, a lot of people think that if you haven’t studied a musical instrument by the time you are twenty then it is already too late. Also, people who didn’t study music as children, or who had a horrible time learning an instrument when they were kids, often declare themselves to be “unmusical” but they would “love to be able to play an instrument.” If you ask such people about any other skill they would like to acquire, such as making pots or knitting, they don’t declare themselves to be “unpotterly” or “unknitty,” they quite sensibly say that they probably could do it if they bought the equipment and took some lessons. They realize that they would probably never be able to compete with professionals but could eventually produce worthwhile stuff and have fun in the process.

There is general agreement that anyone can acquire almost any skill to some level of competence. But music is considered a special case—apparently you’re either musically talented or you’re not. Thankfully this view is entirely wrong: playing a musical instrument is just a skill to be learned like any other. Some people (especially children) pick up the skills involved faster than others (which is true of any skill), but everyone gets better with time and effort.

Another myth about music is that it takes years to learn an instrument. This is only true if you have very high expectations. If you want to play Beethoven sonatas in public, then yes, it will take more than ten years and you will have to practice for more than an hour a day. If, on the other hand, you want to play a Bob Dylan song at a campfire singalong you could probably be ready in a month if you practiced for a few minutes on most days. By the end of the year you could have more than a dozen songs which you could play. It is also very important to remember that learning an instrument is a lot of fun from the beginning. The only pain in the neck is that it involves a lot of repetition—but even that is OK when you can hear yourself getting better and better.

One of the most daunting things about musicians is the way they seem to be able to remember an inhuman amount of notes and regurgitate them at will. This is particularly true of musicians playing classical music from memory: sometimes the musician has to produce thousands of notes in exactly the correct order and if they get even one wrong it will be noticed by the audience. If a non-musician sees this sort of feat it puts her off the idea of learning an instrument because she is sure that her memory (and fingers) couldn’t work that well.

Without in any way diminishing the achievement of such performers, it is useful to know that they are being assisted by something known as “muscular memory.” Obviously muscles can’t actually remember things, but complex sequences of muscular movement can be stored by the brain as a single memory. If this sounds a little unlikely, just think about how little mental effort and memory you need in order to tie your shoelaces every morning. Next time you tie your laces just watch your fingers—it’s an amazingly complicated set of muscular movements, but your brain just sends out a single instruction, “tie shoelaces now.” A trained musician can render a whole piece of music down into a sequence of linked “shoelace-tying” sets of instructions. The brain is not sending out instructions for each finger movement; it’s saying “next comes the bit with the jiggle in the middle; now there’s the bit with the three loud chords.” Getting your brain to do this for a piece of music requires a lot of repetition or practice—but there is nothing magical about it. The magic is in the sounds we create and how people respond to them.

So those of you who have been saying “I’d love to play a musical instrument but I’m just not musical” can go down to the music shop on Saturday and buy an instrument. Everyone is “musical”—becoming a musician is simply a matter of learning a skill. You will be worse than some and better than others but you will be a musician.

If you have decided to take the plunge, the following notes might help you choose the most appropriate instrument—all instruments involve a learning process but some are kinder to the beginner (and their neighbors) than others.

Choosing an instrument

There are far too many instruments in the world for me to list them all here, but I can give you some pointers about some of the more common ones. Musical instruments can be categorized in a number of different ways. For example, there are instruments which can only produce one note at a time (such as flutes), ones on which it is difficult to produce more than one note at a time (such as violins) and those on which it is easy to produce lots of notes at once (such as pianos).

Another categorization which may be useful to a beginner is that some instruments have definite places where you put your fingers to get a certain note (e.g., pianos, flutes, guitars), and some instruments don’t (e.g., violins and trombones). For those of you who have never held a violin or trombone, this may need some explanation.

To take the simplest case of an instrument with set places for your fingers for each note, look at the piano. In the illustration below you can see that if I want to play the note we call “middle C” I just have to press the correct key. Pressing that key will always produce that note and I can’t get that note by pressing any other key. Because the key itself is quite large compared to my fingertip, I don’t have to be very accurate in hitting it, so long as I miss the keys on either side of it. (By the way, I’m assuming that the piano has been tuned.)

To hear the note “middle C” on a piano, all I have to do is press the correct key with one finger.

Now let’s have a look at how you get notes from a guitar. In the illustration opposite, you can see that I have shortened the string I am about to pluck by pressing one of my fingers on the neck of the guitar behind one of the frets. When I pluck the string, I will get the note relevant to the length of the string between the fret and the bridge of the guitar. Once again, I don’t have to be extremely accurate—my finger can be right up against the fret (as in the left-hand photo below) or a few millimeters away from it (as in the middle photo). The note will be the same in both cases because the position of the fret determines the note produced, not the exact position of my finger.

a.

b.

c.

To get a chosen note on a guitar I need two fingers. One finger plucks the string and a finger from the other hand presses the string against the neck of the guitar to trap it over one of the frets. As is the case with the piano, my fingers only need to be accurate within a few millimeters. The finger positions shown in the two illustrations produce the same note because—even though my finger has moved—the fret stays in the same place. The final photo shows the bridge of the guitar, which holds the other end of the strings.

If we now look at a violin, you can see that there are no frets—the pitch of the note produced is determined by the exact position of your finger as it traps the string against the neck and makes it shorter. Wherever you put your finger, you get a note—but only a very small percentage of those notes will be the ones you want. In this case the position of your finger has to be accurate within a millimeter or so.

The lack of frets on a violin neck means that it is much more difficult for a beginner to identify where to put their finger down to shorten the string. Also, the position of the finger must be accurate to within a millimeter or so.

If you want to play the first three notes of “Three Blind Mice” on a piano, you use just one finger to ding out “E, D, C”—it takes about half a minute to learn and you can sound proficient in two minutes. To play the same notes on a guitar involves both hands (one for plucking, one for the frets). It takes a little longer to learn and to become proficient, because frets are not as easy to use as piano keys. Nevertheless you should be making a convincing “Three Blind Mice” noise after about twenty minutes: you learn which frets you have to get your fingers behind for each note and you only have to be accurate in your finger placement to the nearest few millimeters.

The situation is entirely different if you now try to play the tune on a violin, even if we ignore the fact that using the violin bow is pretty difficult in the first place. Let’s imagine that you have had weeks of training on the use of the bow, but this is the first time you have tried shortening the strings by pressing them against the neck of the instrument. There are no frets and there is nothing to use as a visual guide, so it’s very difficult to know where to put down your fingers. If you press your finger down even two millimeters away from the correct place you will produce a note which is noticeably wrong. Also, because you have to hold the instrument up under your chin, you’re looking along the neck and it’s difficult to judge these distances properly.

Taking all this into account, I think it’s perfectly reasonable to declare that the guitar and piano are kinder to total beginners than the violin. However, don’t be misled into thinking that a trained violinist is more skilled than a trained pianist or guitarist—nearly all instruments require similar amounts of skill once you have progressed beyond the beginner stage. “Why,” you might well ask, “if the violin is more difficult to start with, doesn’t it remain more difficult?” The answer to this question is that musical training is designed to get the best out of every instrument. Within a few weeks a trainee pianist will be asked to play more than one note at once most of the time. By the time he has been learning a couple of years he may be playing four, five or even more notes at the same time. Violinists will only rarely be asked to play more than one note at a time and will not attempt even two together until they have been training for several years, because it is much more difficult to do on the violin. In each case the musician is trained within the limits of the instrument she is trying to master.

Which instrument should you take up? Well, of course, that’s up to you. I wish you luck whichever one you choose. My only advice is that, if you are over twenty and you’ve never played an instrument before, don’t put yourself off by starting with one of the instruments which are really tough on total beginners—the slide trombone, French horn, bassoon, violin, viola and cello fall into this category.

Slide trombones, for example, make a marvelous noise but they involve more skill than most instruments for the beginner. To start with, you have to learn how to use the sliding bent tube which makes the instrument longer or shorter—a longer tube gives a lower fundamental frequency. There are seven different correct positions for this slide but no indication of where they are—you just have to practice getting it right. Once you have pushed the slide into the correct position, you can get one of about ten possible notes depending on the type of farting noise you make with your lips—which is determined by how tightly you press your lips together and how hard you blow. These different notes are the harmonics of the tube length you choose by moving the slide. In the early stages of learning it is very easy to get completely the wrong note, either by putting the slide in the wrong place, or by blowing too hard or pursing your lips in the wrong way. I have a lot of admiration for people who learn one of the instruments which are extra tricky for beginners, but my admiration is tempered by NIMBYism—I wouldn’t want a trainee trombonist living next door.

If you want to take up an instrument you blow into, I suggest starting with the flute, saxophone or trumpet, instruments with clear positions for your fingers. You can then change instruments after a few months if you want to. You might also want to consider portability and storage (it’s easier to store and carry a clarinet than a harp), and how satisfying the instrument is to play solo—because you will be practicing on your own most of the time. For example, there is a far more interesting repertoire of printed music for the solo piano than there is for any other instrument. By the way, if you do decide to go for the piano, I recommend one of the high-quality electronic keyboards rather than a real piano, because you can practice with headphones on without disturbing your neighbors, and you can fool around with all the other sounds they make if you get bored practicing.

Finally, I would suggest that you join an evening class or find a teacher. You can make decent progress if you have a half-hour lesson once a week or so and then practice for an hour or so every week.

How do composers learn to compose?

To most non-musicians the process of composition is totally mysterious. Other jobs or hobbies seem pretty straightforward by comparison. If you spend a long time training, you can become a dentist, portrait painter, crane driver or gardener—and the sorts of things you would have to study have very little mystery to them.

Training to compose music of any sort always involves a lot of trial and error. If you are starting a rock band with your friends you usually start off playing other people’s music, but eventually you might start to write your own. This can either be a collaborative thing or might involve just one writer. Initially the music will be very imitative of your favorite musicians, but eventually your own musical personality will come through. This type of informal “on-the-job” training for writing music is very common for rock and pop musicians.

It is also possible to study composition at a college or university. At one point I studied composition, and my friends used to ask me what I did with my tutor—apart from drink tea. I suppose most of them thought that I would think up a tune and then my tutor and I would mess about with it until it became a piece of music. Nobody really understood how you could train to do something as “artistic” as composition. Eventually, to explain what was actually going on, I developed the following analogy.

Imagine you are training to be a TV comedy scriptwriter—you are a fairly amusing person and you have developed some writing skills. You have thought up a funny situation but it just doesn’t work very well once you have written it down. If you take the sketch to your tutor, she will use her experience to try to find ways of getting the maximum amount of audience pleasure out of your original idea. She will probably suggest changes, such as:

• maybe it’s too long or too short…

• maybe all the interesting stuff happens too early or too late…

• maybe there are too many or too few people involved…

• maybe you need to remove a line which gives the punch line away too early—or add one to make the joke clearer…

The tutor (if she is any good) will not work directly on the piece with you—but she will suggest specific areas you might want to look at.

This is basically how composition is taught—you go in with a musical idea and the tutor assists you with suggestions like the ones above and also helps with the technical issues. In music there are lots of technical issues. If you are writing for instruments you don’t play yourself you need to learn a lot about them if the music is to be playable. There are obvious simple mistakes—“flutes can’t go that low”—and less obvious ones—“this trumpeter’s lips went completely numb about two minutes ago.”

So the sort of training you get is pretty straightforward, and a lot of it is similar to the sort of training you would get as a scriptwriter—it’s all about content and timing.

As far as the original musical idea is concerned, that’s no great mystery either. You don’t necessarily start with a tune—it might be a rhythm or a “bass line” (a repetitive bass accompaniment). It might be something you found yourself humming or something you misplayed on the piano. For example, the English composer Vaughan Williams based the second movement of his Third Symphony on a single mistake he heard an army bugler make while he was working as an ambulance driver during the First World War.

Anyone can make up a tune. Just hum to yourself for a couple of minutes and eventually something worthwhile will pop out. Or you could sit at the piano playing with one finger quite slowly—occasionally tunes will appear. The difficulty is not in producing tunes. It’s in remembering them and then developing harmonies and, finally, writing it all down or recording it. This is where musical training is useful; it will help you to remember your tune and write it down. Unless you can record your idea or write it down, it will be difficult to work on and improve it and, in any case, nobody else will ever be able to hear it because you will probably forget what you wrote.

So whether you are writing an opera or the next rock classic, the basics of musical composition go like this:

1. Come up with one or two (generally very short) musical ideas.

2. Write them down or record them (there are computer packages to help you).

3. Use them to develop accompanying music (i.e., if you started with a tune, try different accompaniments; if you started with a bass line, develop a tune and/or chords).

4. Write it all down or record it.

5. Now organize the overall timing. Just like a well-told joke, does it need to be made longer by repeating bits? Does it need thirty seconds of droning, mysterious introductory music?

6. Write it all down or record it.

And there you are—your own composition. At first you might only produce the musical equivalent of “knock knock” jokes, but eventually your stuff will become more sophisticated and (hopefully) enjoyable to others. (If you make a fortune from following this advice, please send a check for 5 percent of your annual income made out to “John Powell”—credit cards are also acceptable.)

While we are on the subject of composition, I would like to offer you a few notes on a subject which baffles a lot of people when they first encounter classical music.

Why do classical pieces have such long, complicated names?

If you listen to any classical music station for an hour or so you are bound to hear the announcer say something like, “That was the allegro first movement from Mozart’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 17 in G major, K453” or, “Next, we are going to hear Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Opus 26.” This is one of the reasons that many people find classical music unapproachable—even if they hear something they like, it’s difficult to know how to ask for it in a shop. The pieces need to have names if we are going to buy a recording or discuss them—but why do the names need to be so complicated?

One way to disentangle the origins of the names is to explain a few examples. Let’s start with the Mozart one above.

Decoding “The allegro first movement from Mozart’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 17 in G major, K453”

CONCERTO FOR PIANO AND ORCHESTRA

The two most common types of classical music which involve an orchestra are the symphony and the concerto.

A full orchestra playing a symphony involves about a hundred musicians but generally they don’t all play at the same time. The composer chooses which instruments do what at any given moment. If the music is to sound wistful, the composer might write a tune for a single oboe, accompanied by violins and a harp. The same tune might be reintroduced later in a more dramatic section played by brass instruments, accompanied by drums. These changes in instrumental tone help to sustain the listener’s interest. The performance of a symphony can therefore be described as an orchestra all working together as a team—passing the musical work around and occasionally all playing together.

The only difference between a symphony and a concerto is that a concerto also involves a soloist who sits or stands at the front of the stage and shows off throughout the piece. The soloist might be playing any instrument (in this case it’s a piano but there are also concertos written for cello, guitar, trumpet, etc.), but the point of the solo instrument is that it adds extra drama to the music. The soloist does more work than any other musician, as he rarely takes a break (he also gets paid more). For a concerto the composer might write music for strings and soloist together; followed by brass and soloist; soloist alone; full orchestra alone; then full orchestra with soloist, and so on. Musical “conversations” or even “arguments” can be set up where the soloist is playing one thing while the orchestra is responding with something else. Basically the on/off relationship between the soloist and the orchestra makes the music even more varied than a symphony—and also more interesting to watch at a concert because you have a “star of the show.” This description only fits concertos written since around 1800. Before that time the word “concerto” just meant “a piece of music,” which might involve a soloist (as in Bach’s Concerto in A for Violin and Orchestra), or might not (as in Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos).

When we discuss a particular concerto, we usually refer to the solo instrument as well as the orchestra, so we get names like “Concerto for Piano and Orchestra.”

FIRST MOVEMENT

Classical music enthusiasts might find the following prosaic description of the organizational motives of composers very difficult to accept, but it is important to remember that composers have always needed to have a professional attitude towards their music. Swanning around, insisting that you are an “artist,” won’t pay the rent.

Traditionally, classical music was written for live concerts, a straightforward entertainment which resulted in the composer and the musicians getting paid and everyone else having a good time for an hour or two. From the point of view of a working composer like Mozart, the following two guidelines are important:

- The orchestra should change pieces every few minutes to keep interest levels up—so the audience doesn’t start chatting, nodding off, or playing tic-tac-toe.

- The pieces should be presented in groups of three or four to cut down on the amount of disruption and effort involved in applauding.

From these two fairly simple rules, most composers from about 1750 on have presented three or four individual pieces of music (each between five and twenty minutes long) as parts (or movements) of a bigger piece which they call a symphony, concerto, or in the case of solo instruments, a sonata. There is a short silence between each movement during which you are not supposed to clap—yet another source of confusion to the newcomer. You are only supposed to applaud at the very end.

In some cases there might be a musical link between the movements, but they can also be specifically designed to clash (in order to keep interest levels up). In the piece we are discussing there are three movements: the first is about thirteen minutes long; the second is about ten minutes; and the third is about eight minutes.

ALLEGRO

Apart from having different tunes, the movements are often pieces with different speeds: it is common (but not a rule) to start with a fast movement, then have a slow romantic movement, and then finish with another fast movement. The movements can be referred to either by their number (first, second, etc.) or by their speed, which is usually indicated in Italian, French or German. In this case the word “allegro” is simply the Italian for “fast.”

Having given us the number of the movement, our radio announcers do not need to tell us the speed as well—but they often do.

MOZART

Obviously we need to know the name of the composer if we are to track the piece down.

NO. 17

Mozart wrote over twenty piano concertos, so we need to know which number it is. The concertos are numbered in the order in which he wrote them.

IN G MAJOR

This is a totally pointless piece of information unless Mozart only used G major for one of his piano concertos—in which case this information could be used instead of the number to identify it. Apart from this minor point I don’t know why everyone involved in classical music broadcasting keeps telling us what key things were written in—it makes no difference to any of us.

K453

A music historian called Köchel (pronounced “Kerkul”) spent a large part of his life cataloging Mozart’s music and numbered every piece in the order it was composed. So now we refer to each piece by its “K” or “Köchel” number (as well as the separate concerto number).

COULD WE SHORTEN THE NAME OF THIS PIECE?

Yes, we could: the radio announcer could have given us all the information we need by calling it any of the following:

- “The allegro from Mozart’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 17”

- “The first movement from Mozart’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 17”

- “The allegro from Mozart’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, K453”

- “The first movement from Mozart’s Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, K453”

Let’s have a look at a few more examples.

Prokofiev’s Piano Concerto No. 3 in C major, Opus 26

This is very similar to the title of the Mozart piece, except for the word “Opus,” which means “piece of work.” In music the opus number generally refers to a piece of published work—such works are numbered chronologically—so this piano concerto was the twenty-sixth work which Prokofiev managed to get published (only very high-quality pieces get published).

Tchaikovsky’s Symphony No. 6, Opus 74, the “Pathétique”

As I said earlier, a symphony involves an orchestra without a soloist—although the composer might choose to use individuals for short solos during the piece. Most symphonies have four movements, each of which is usually between five and twenty minutes long. Symphonies are numbered and sometimes also have names—as in this case, the “Pathétique,” or “sad.”

The Prelude, Fugue and Sarabande from Bach’s Lute Suite No. 2 in C minor, BWV997

Bach, and other composers of his time, often grouped together about six short pieces into a suite. These suites usually began with a prelude (“pre” meaning “before,” and “lude” meaning “play”) and then were followed by several dances. The fact that they were called dances merely meant that they had the distinctive rhythm of certain dances (in the same way that a composer might call a movement of their symphony a waltz because it has an “um-pa-pa” rhythm), but you were not supposed to dance to them. The dances in Bach’s suites had names such as sarabande, gigue and minuet. The rhythm of a sarabande is like a slow waltz.

The fugue in this title is a word which means “flight” in English. As far as music is concerned, a fugue is generally a difficult piece which involves lots of counterpoint—the playing of more than one tune at the same time.

This particular suite was written for a single musician playing the lute, which is similar to a guitar. The BWV number is, like the K number for Mozart’s work, a catalog number to identify the piece accurately.

Beethoven’s Piano Sonata No. 14 in C sharp minor, Opus 27, “Moonlight”

Sonatas are almost always pieces for one or two instruments and are generally in three or four movements (for the usual reasons—see my earlier comments on “First Movement”). A piano sonata is always written for a solo piano but a violin or cello sonata will usually include a piano accompaniment. (There is a rather stingy tradition among composers, concert promoters, radio announcers and CD sleeve designers to relegate the pianist to the rank of “accompanist” rather than treating him like one half of a duet—which would be closer to the truth.) By the way, Beethoven didn’t call this piece “Moonlight”—he called it “Sonata Quasi una Fantasia.” One of the critics who reviewed the piece, a man called Ludwig Rellstab, wrote that the first movement reminded him of the moonlight on Lake Lucerne—and the idea stuck.

Now that you know all about the opus numbering, key naming, and so on, we can deal with a few more bits of classical music jargon.

STRING QUARTET

A string quartet is written for, and performed by, two violins, a viola and a cello. There are usually four movements.

STRING TRIO

A string quartet without the second violin.

STRING QUINTET

A string quartet with an extra viola or cello.

PIANO QUINTET

A string quartet with a piano.

CLARINET QUINTET

A string quartet with a clarinet.

CANTATA

A piece for choir and (usually) orchestra with occasional solo singers. These are often quite long (an hour or so) and made up of lots of five-or ten-minute movements.

CHAMBER MUSIC

The original idea for chamber music was that it should be performed by a small number of musicians in a room (chambre) rather than a concert hall. Nowadays the term just means any music written for up to about ten musicians (such as string quartets or quintets).

LIEDER

“Lieder” is the German word for “song.” The term “lieder” generally describes a solo singer (with clasped hands and a fancy dress, or clasped hands and a bow tie) singing to a piano accompaniment.

Now we have decoded the titles of classical pieces, I would like to stay on the subject of classical music for a little while, in order to answer another puzzling conundrum.

How do conductors justify their enormous paychecks?

If you go to a classical symphony concert you will find that there are about a hundred people on the stage doing all the work while one person, with their back to you, wafts a stick around. Surprisingly, it is the stick-waggler who is the star of the show—and the best paid member of the band. To many this arrangement seems unfair. Apart from the fact that waggling a stick is demonstrably easier than playing an instrument, no one in the orchestra seems to be paying a blind bit of notice to the waggles of the stick in question.

In fact, by the time everyone gets on stage, the conductor has done most of her work. This preliminary work takes place during rehearsals and involves making a lot of choices about speed, balance and loudness. “Why do these choices need to be made?” you might ask. “Didn’t the composer make all these choices in the first place?” Well, the surprising answer to that question is “No.” The amount of information the composer writes down on the printed page varies according to the composer and the historical date of the composition: for example, music written before 1800 often has no indication of the speed at which it should be played, or any other extra information—all you get on the page is a stream of notes.

Music composed in the past 200 years usually has information written alongside the notes telling the musicians when to speed up or get louder, but these instructions tend to be rather vague. A piece of music will commonly state what speed to start at (by means of a metronome mark, which tells you how many notes per minute you should play), and might then tell you to slow down for a while—but will not generally indicate how much to slow down. Similarly, there will be various indications on the written music as to when to play louder—but only a rough indication about how loud to get.

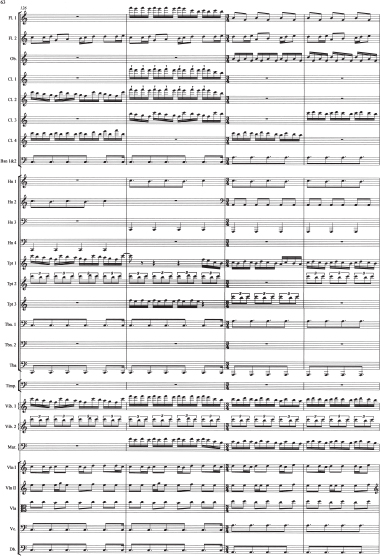

You might wonder why composers aren’t more exact in these matters, but the point is that a single page of orchestral music already contains hundreds of pieces of musical information, as you can see in the example below, and more detail might cloud the musical message rather than clarify it. In any case, a bit of variability adds interest to each new performance. One of my favorite stories about this flexibility concerns the Finnish composer Sibelius. He was listening to a rehearsal of his violin concerto when the violin soloist asked him a question about how to interpret a certain passage. “Do you prefer this passage played like this… [he then played it with a very sweet tone], or like this… [playing it with a dryer tone]?” Sibelius thought for a few seconds and then pronounced judgment: “I prefer both versions.”

Apart from all this vagueness about loudness and speed, there is the choice of the overall balance of the sound of the orchestra, which will, of course, change during the piece. Quite often the written music gives no indication that, for example, the violins need to get gradually louder during a particular section because they will be taking over the tune from the woodwind instruments in the next bit. The conductor can color and shade the overall sound of the piece by deciding which instruments should play loudest at any point. This is not as straightforward as it might seem because you don’t always want to do the obvious thing of playing the tune loudly over a quieter background harmony.

There are, in fact, hundreds of important decisions to make during rehearsals-and it’s the conductor’s job to make them all. All conductors make different, equally valid decisions and some of them change their minds about how a piece should be played as they get older. This means that each concert or recording of a piece of classical music is unique, which is why people often have several recordings of the same piece.

A typical page from an orchestral piece, showing that each page contains hundreds of pieces of information. In this case, all the information represents about twelve seconds of music for twenty-seven different types of instrument, all playing at the same time (e.g., the top line is for a flute and the bottom line is for the double basses).

Things are better organized nowadays, but toward the end of the nineteenth century it was difficult for the conductor to pass on his ideas about the music to the orchestra, because many members of the orchestra weren’t actually there for rehearsals. Hangovers, illicit love affairs and better paid gigs meant that a lot of the orchestral members had better things to do in the afternoons than go to rehearsals, so they paid “deputies” to take their places. The deputy would play the instrument of the missing musician to make sure there were enough violins, clarinets, or whatever, at the rehearsal. This was fine if only a few people did it, but it eventually became fairly common for over half the orchestra to send deputies. Sometimes the deputy would also play the concert, but generally a large number of the players at the concert had not been at the rehearsal.

Another problem conductors had to deal with in those days was naughty percussionists. In a lot of orchestral scores you need two or three percussionists to do a lot of impressive banging and crashing at particular climaxes of the music, but sometimes they have nothing to do for twenty minutes or more. Obviously, these long breaks bring out the natural tendency of the musician to slink off to the pub for a quick pint. Back in 1896 Sir Henry Wood (the conductor who invented the Proms) found that the only way to stop the slinking percussionists was to lock the exit doors. In his autobiography he describes the result: “I would see these fellows creeping up, one by one, bending double in the hope of being hidden by the music stands. They would gently push the bar of the exit door, following up with a good shove. They would then return, creeping along, bent double and with a puzzled expression on their faces—perhaps to watch someone else going through the same antics.”

Of course, in these modern, professional times, percussionists are paragons of virtue who would never dream of nipping round the corner for a quick one in the middle of a symphony.

Once everyone is on stage and playing, the conductor will spend his time nodding, winking and glaring at the musicians as well as wafting that stick around. Some of these signals are simply to remind someone that, after not playing for seventeen minutes, she has to get ready to play that big fanfare. Other signals vary in meaning from “Don’t forget to play this bit very quietly” to “You’re fired, you butter-fingered oaf…” As far as the stick wafting is concerned, the up-down, side-to-side action of the stick is used to indicate the beats in each bar and thus the speed of the music.* The reason why most of the orchestra aren’t watching most of the time is that they are busy reading the music and can only glance up occasionally to get information from the conductor.

Improvisation

Improvisation is making music up as you go along. Various sorts of music involve different levels of improvising: if you listen to a symphony written between 1800 and 1900 the total level of improvisation involved is—zero. At the other end of the scale, you get jazz musicians like Keith Jarrett, who can turn up at a venue and improvise the whole concert.

As far as improvisation is concerned, the first step is usually to play your own versions of well-known tunes. This often means playing the tune as it was originally written to start with, and then making up your own variations. The variations often involve strategies which a musician has learned, which can be applied to any tune. For example, imagine that you are one of those irritating, glazed-eyed hotel lobby pianists improvising on “My Way” to make it last until your next coffee break. If you want to make it sound romantic, play it slowly, with lots of pauses, and accompany the tune with chords split into arpeggios (where you play the notes of the chord one after another rather than all together). If you want it to sound hymn-like and spiritual, simplify the chords and play one chord for every strong beat of the rhythm. Hymns sound like this because they are specifically designed to be performed by non-expert musicians. If you want to make it sound heroic or dramatic, then don’t let the music rest on the long notes; replace them with repeated notes. Of course, if you carry on doing this for too long you are likely to find a certain author creeping up behind you with a garrote in one hand and body bag in the other.

This type of variation/improvisation can, of course, be done by groups of musicians as well as solo players. Good musicians will not only arrange the notes in different ways, they will introduce new notes and change the tune. When they are improvising, the best jazz musicians merely hint at the original melody every now and then—it’s like getting a glimpse of a familiar landmark when you thought you were lost. It might sound a little chaotic at times, but improvising musicians learn lots of techniques for re-establishing order whenever they want to—and can steer the audience through an emotional cycle of familiarization, disorientation, expectation and gratification. Or, in my girlfriend’s view of jazz, disorientation, irritation, horror that it might never end, and relief when it does (her words, dictated to me as I write this).

Another type of improvisation involves a soloist or members of a band making up new melodies over a well-known sequence of chords or a bass line. This is epitomized in the lead guitar solo. Lead guitarists love lead guitar solos—everyone else repeats something pretty mundane, and we get to prance and pose. We’ve got between two and twenty-two minutes to get back to the tune and it doesn’t really matter what we do in the meantime as long as it’s loud and has lots of notes in it. There are examples of musically meaningful guitar solos, but the guitarists involved are just being unnecessarily clever and letting the side down. One of the commonest platforms for a lead guitar solo is the twelve-bar blues. The twelve-bar blues is not an allusion to the previous eleven pubs you’ve been to that evening, trying to forget the fact that your girlfriend just left you because you insisted on listening to too much jazz—it’s a very simple musical structure which is the basis of most blues and a lot of other pop music.

The twelve bars are just twelve short time periods. As we saw in the previous chapter, music is divided up into bars of time and each of these time periods has several notes in it. In the context of an average blues song, a bar lasts about three seconds and contains four beats, with a slight emphasis on the first one:

dum dum dum dum, dum dum dum dum.

During a twelve-bar blues, the rhythm guitarist churns out a standard sequence of chords. In the simplest versions there are only three chords involved—let’s call them chords X, Y and Z. Although there are quite a few varieties, in a standard twelve-bar blues you might expect the rhythm guitar player to strum chord X for four bars, then chord Y for two, back to chord X for two, Z for two and back to X for the final two of the twelve. This routine then repeats itself, and all the while the bass guitar is also supplying notes in an X–Y–X–Z–X cycle. This simple structure explains why blues bands can play after any amount of alcohol intake, and why their natural habitat is the pub. Over this straightforward musical background the lead guitarists can lark around however they want to, as long as they avoid certain notes which clash with these chords—and thus was the endless blues guitar solo born.

I have no intention of belittling blues bands, because some of them are tough-looking buggers who I wouldn’t want to meet in a dark alley. So I would like to point out that, like many simple musical systems, there are lots of added complications and nuances which the best players have to master before anyone will pay them to perform.

Improvising in Western music is not a new thing; it just became unfashionable in nineteenth-century classical music. Back in the eighteenth century it was very popular: for example, one of Bach’s most well-known pieces, the Brandenburg Concerto No. 3, consists of three movements but only two of them are written out in full. The written music for the middle movement is just two chords long—which would only last about ten seconds. It is possible, of course, that Bach was called away in the middle of his writing to take part in the birth or, indeed, conception, of one of his twenty children, and forgot to finish it. The more traditional historical view is that the second movement would consist of a three-minute viola solo by Bach who would then nod at the rest of the band—and they would finish off with these two chords. Nowadays, in most recordings of this piece, the musicians chicken out on the improvisation and just play the two chords—and who can blame them? I certainly wouldn’t want any of my own improvised drivel sandwiched between two pieces by Bach.

Improvisation is common to all musical societies. For example, Indian traditional music concentrates heavily upon it. The training of a Western classical musician involves lots of repetition in an attempt to play the notes written by a composer correctly. Traditional Indian musical training is all about how to compose your own music on your instrument as you go along. The idea is that you have a group of notes as your basic building blocks, and you use them to improvise a piece lasting several minutes. Each group of notes, or “raga,” is associated with a mood and a time of day.

The ability to improvise well is a highly respected talent and it can lead to some interesting interplay between the musicians involved. It can even become competitive, as the musicians drive each other to new heights. Speaking of competition, there are international improvisation competitions between classically trained organists. You can’t cheat by playing something you composed earlier, because they hand you a brand-new tune to base your improvisation on only an hour before you begin. After you are given the tune, you have to make up a piece of music on a big church organ, in front of a crowd of other competitors and their friends. So, no pressure there then…

Whatever level you reach, improvisation is fun for the player. Even if you are a complete beginner, you can make up your own tunes really easily if you have access to a piano or similar key-board. Use one finger from each hand and play only the black notes. This automatically gives you a pentatonic scale—and it’s really quite difficult to make a horrible noise using this type of scale. If you put your foot on the right-hand pedal the notes will merge into each other, which gives a great “full” effect, but you need to raise your foot and put it down again quickly every five or six notes. This pedal lets the notes ring out for a longer time, and the notes of your melody will overlap and harmonize with each other. Every time you raise your foot you kill that group of notes. You need to do this because too many overlapping notes sound messy. The pedal on the left gives the notes a very short lifetime and is for real pianists—not for the likes of you and me.