Singers are simultaneously musician and instrument, inseparably integrated. When the time comes to perform, everything you have done to optimize your voice and develop your technique is set in motion by your imagination. From a strictly mechanical perspective, the breath would seem to be the generator for the vocal instrument; however, I argue that expressive intention could more accurately be said to serve this role, not merely poetically but in a literal neuromuscular sense.

The technical coordination you cultivate in the studio becomes artistically valuable only when it enables the translation of your ideas and feelings into sound. Vocalises serve to expand your range and enhance your skill at registration, but it is your ear that audiates and thereby tunes precise pitches and eliciting desired weight and dynamic levels from your vocal folds. Articulatory coordination and balanced resonance are developed through exercise and repetition, but it is through audiating each vowel and consonant that you activate the required anatomy needed to produce them. The characters you breathe life into, the narratives you weave, and the emotions you evoke must arise from creative impulse before they can be channeled through your voice.

Instrumentalists make music by manipulating an inanimate object. For them, mastery requires developing a sense of seamless integration with their instrument. The necessity of channeling their artistry through an external device rather than their own bodies would seem to set them at a disadvantage in comparison with singers, but the structural distinction between musician and instrument actually makes their job easier in some crucial ways:

Instrumentalists can visualize and feel nearly everything they are doing. They receive visual and tactile feedback from their interactions with their instrument. The muscles in the hands, arms, and mouth are relatively rich with sensory neurons; by contrast, many significant components of vocal anatomy, including the intrinsic muscles of the larynx, provide little to no sensory feedback.

They can distinguish between technique and instrument function with relative ease. Instrumentalists can simply acquire a fine model and rely on repair specialists to ensure it remains in top working condition. When a reed or a string ceases to respond properly, they can replace it, whereas you will rely on a single pair of vocal folds throughout your entire career.

The way they perceive their own sound is likely to be almost identical to the way their listeners perceive it. To a great extent, they are able to hear their own sound amplified by the acoustics of the room they’re playing in rather than through the distortion of bone conduction.

The instrument they are playing is nearly identical to all others of its kind. They can emulate those with more advanced skills and compare themselves with their peers fairly objectively. This is far more difficult for singers, as each plays a unique instrument.

For singers, the difficulty of differentiating musician from instrument can make it difficult to discern whether a challenge you’re experiencing stems from a technical or physiological issue. Nevertheless, I find the inherent integration of artist and instrument that singers alone enjoy to be highly advantageous, provided that we respect the relationship between mind and body and understand how we can benefit from that connection.

Classical singing technique can unlock the full power of the acoustic human voice, harnessing emotional extremes and vocally transmitting them to our audiences. We can set listeners’ auditory apparatuses in motion, creating a sympathetic vibratory connection that exhorts them to feel what we are feeling.

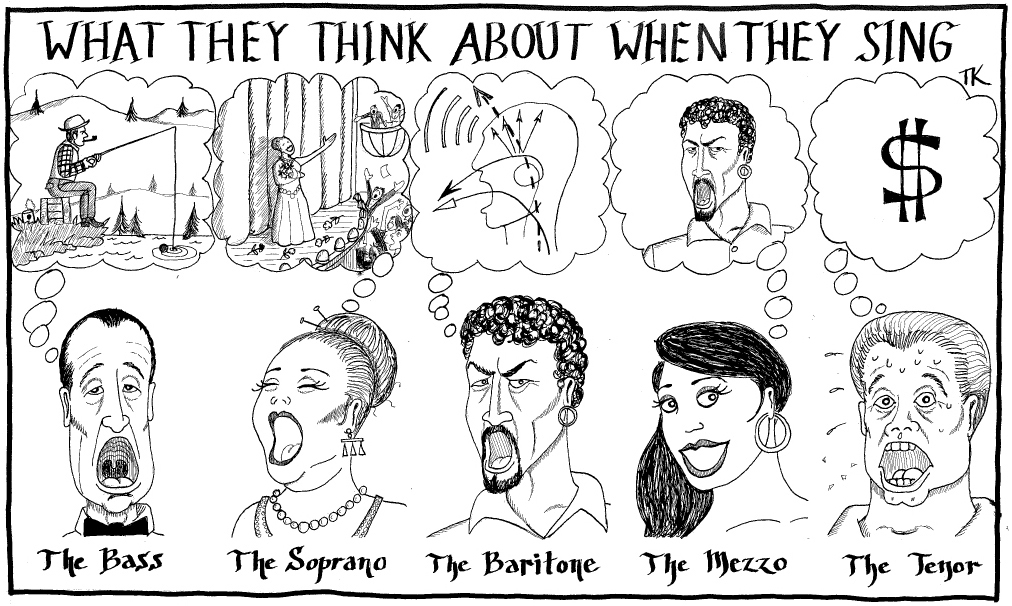

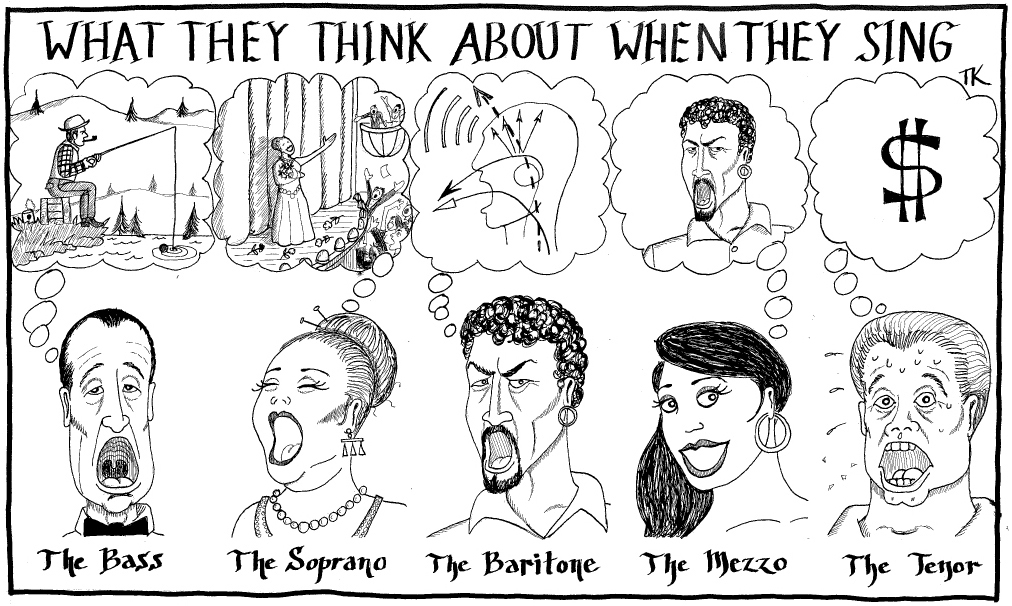

However, the voice never lies—everything you are thinking and feeling will come through in your singing (see figure 5.1). If you fully immerse yourself in the experiences and emotions of the character you are embodying, you will communicate them incisively to your listeners; likewise, if you become consumed with a need to micromanage your technique or wrestle with stage fright, those activities will color your performance, because the voice is physiologically wired to respond to and communicate all your thoughts and feelings in real time.

The more vulnerable, passionate, and sincere your intentions, the more impactful your singing will be. A singer with a flawed technique can deliver a compelling performance because dramatic and musical commitment sometimes transcends imperfect coordination. Yet a singer who has little to say can deliver an impeccable performance but leave listeners cold, because virtuosity for its own sake cannot compare with raw passion.

Figure 5.1 What they think about when they sing. Thom King.

Hold your left arm straight out in front of you. Bend your elbow. Straighten your arm out again. How did you do that?

There are a couple of ways to answer this question. It could be said that biomechanically, you contracted your biceps, causing your elbow to flex; then you relaxed your biceps and engaged your triceps, which resulted in your arm returning to an extended position. It is equally true to say that mentally, you tasked your highly efficient neuromuscular system with executing these movements, causing a group of motor neurons to deliver your instructions to and activate the requisite musculature, with minimal conscious thought or physical effort on your part.

This mental procedure is the means whereby you are able to adjust your vocal folds to the precise length required for a given pitch, contract your diaphragm to take in the quantity of air you need to perform a phrase of a certain length, and arrange your tongue, jaw, and lips to articulate a desired vowel. Your intentions activate the neuromuscular system to initiate movement. The process may seem more mystical where the voice is concerned than for elbow movement—I find it quite magical that the vocal folds can be tuned with such specificity in response to a musical impulse!—but if you think about it, there is something magical about all human movement, as well as our ability to condition our bodies to learn new skills and improve upon old ones.

Consider the ways it is possible to augment the function of your elbow. You can improve its range of motion. You can condition it to handle greater loads by strengthening the muscles surrounding it. You can develop speed and coordination by training and repeating the movements necessary to catch and throw a baseball. But when the time comes for you to field that ball and throw it to a teammate, it is the intention to do so that reflexively sets the whole process in motion.

So it is with vocal conditioning. Flexibility, strength, and coordination are cultivated in the practice room via well-controlled movement and repetition. When the time comes to perform, you hand the controls over to your expressive intent and trust your instrument to reflexively respond.

Effective conditioning also benefits from clarity of intention. Whether you are working to balance out the musculature that supports your alignment, improve laryngeal range of motion, or coordinate your articulators, your work in both the studio and the gym is most productive when you set a well-defined agenda and commit to a procedure that will yield the results you desire. And not only the body but also the mind itself can be made more powerful through such conditioning.

The Importance of Equanimity

Learning to sing is an open-ended endeavor. No matter how skilled and experienced you become, there will always be more to learn, refine, and express. Singing is thus both incredibly fulfilling and quite humbling. Every breakthrough reveals a higher potential level of achievement, so each success confers insight into how much more there is to learn.

Vocal progress involves exposing areas of resistance, weakness, or poor coordination so that you can work on them. Awareness is often curative, and careful observation of a problem is often enough to set in motion a process whereby you will be able to resolve that problem. However, a desire to avoid eliciting ugly or unpleasant sounds and sensations can make unmasking these problems painful. Your progress thus largely depends upon your ability to greet these revelations with equanimity.

It is essential that you remain dispassionate while observing technical flaws in your singing in order to focus your attention and energy on ameliorating them. When observing flaws provokes negative emotional reactions and self-criticism, a crucial opportunity to investigate and resolve them is lost. The most unwieldy sounds you make in the practice room often provide the very best learning opportunities—provided that rather than berate yourself you suspend judgment long enough to observe your actions and explore alternative strategies. Equanimity is therefore one of the most significant skills a singer can possess, as it lays the foundation for the swift and pleasant cultivation of all the other skills you need.

Meditation is a means of enhancing your power of concentration. It trains the mind to observe thoughts, sensations, and other phenomena with detached awareness and expands your ability to direct your focus. While many meditation practices stem from religious traditions, meditation is now commonly taught as a stand-alone technique distinct from any dogmatic origin.

While any activity can serve as a meditative object of focus, when beginning a meditation practice it is best to set conditions that encourage a narrow focus. Try this seated meditation focusing on the body sensations associated with breathing:

1. Set a timer for a modest stretch of time, perhaps ten or fifteen minutes.

2. Sit on a chair or a cushion, assuming a posture that is comfortable but discourages slouching—a position that makes you feel alert but not rigid. Allow your hands to rest on your thighs.

3. Close your eyes and bring your awareness to your breath. Notice all movements and sensations related to breathing:

• All movement in your abdominal area

• The rise and fall of your ribs

• Sensations in your throat, mouth, and nose

• Any movement elsewhere in your body that feels related to the breath

• Any sense of tightening or release related to the breath

• Any changes in how expansive or shallow your breathing seems to be

• Any sounds related to the breath

4. If your mind wanders, gently bring your awareness back to the movements and sensations related to your breath.

5. If you find yourself analyzing or judging aspects of your breathing, again gently bring your awareness back to the movements and sensations related to your breath.

This exercise exemplifies a meditation technique called Vipassana. In the West, Vipassana commonly translates to insight meditation, but the literal meaning of the Pali word is “to see distinctly.” The version of Vipassana meditation that I practice involves observing specific phenomena and identifying, labeling, and tracking the movement of their various components. For example, as part of this exercise you could note breathing sensations of expansion and contraction or differentiate between movements, feelings, and sounds.

The mental skill facilitated by this technique is highly applicable to singing practice. Focused intention is essential when working with the mechanics of breath management in order to avoid being distracted by the sounds and sensations you elicit along the way. Heightened awareness is useful for keeping track of the individual movements of your jaw, tongue, lips, and soft palate during detailed work on articulation. Detached, dispassionate observation can enable you to gently steer your focus away from any emotional reactions you experience in relation to vocal flaws or instabilities in order to concentrate on the actions crucial for their amelioration.

Like meditation, hypnosis promotes states of relaxed focus and awareness; in addition, it encourages greater mental suggestibility in order to reprogram specific patterns of thought and habit. While meditation provides for a general, global elevation of your ability to concentrate, hypnosis facilitates targeted psychological and behavioral shifts.

Thought patterns are habituated and stabilized in much the same way as the movement and postural patterns we cultivate, both consciously and unconsciously. Just as our movement patterns can be changed and fine-tuned, we can learn to consciously redirect our thoughts to habituate more positive and productive patterns.

For example, a history of unresolved intonation or flexibility issues may make you fear you’ll never improve in these areas and cause deep discouragement. This may incline you to focus on past failures, reinforce a belief that these issues are permanent, and make it difficult to take steps to resolve them. Hypnosis offers techniques for replacing such habituated negative thought patterns with more positive, solution-oriented mental feedback loops. If you find yourself thinking, “I’ll never be able to sing in tune” or “I hate how I sound right now,” you can learn to redirect yourself with questions like “What would I like the sound to be? How do I want to feel when I sing this passage? What must I do to facilitate that and enjoy the process?”

Learning and skill retention are most swiftly, effectively, and pleasurably accomplished in a positive environment. When offered encouragement and rewarded with kindness, we feel motivated to absorb new information and optimistic about progress; when offered admonishment and punished with criticism, we will likely react with confusion and pain. Hypnosis can teach us to entice ourselves with carrots rather than threaten ourselves with sticks.

Somatic disciplines are practices that incorporate movement and mindfulness to promote mind/body integration and enhanced awareness. Humans have engaged in such disciplines for millennia—they include everything from ancient yoga and martial arts practices to modern forms of bodywork.

Somatic disciplines can improve physical coordination, kinesthetic awareness, mental focus, and emotional equanimity. They are therefore of immense benefit for singers. I will highlight several that have historically been favored by our community and discuss their potential benefits.

Yoga is a five-thousand-year-old discipline created as a means of cultivating physical, emotional, mental, and spiritual growth and integration. Originating in India and now practiced throughout the world, yoga has evolved into numerous traditions emphasizing different aspects while sharing fundamental principles and procedures: a sequence of poses, each dynamically sustained and slowly transformed to the next, emphasizing mindfulness, acceptance, and expansive breathing.

Singers have long valued yoga for its ability to promote full breathing, balanced alignment, and calm. It encourages you to experience your body as an integrated whole and to appreciate the movement inherent in sustained stillness, which is also essential for developing a consistent musical legato.

Like singing, yoga is an open-ended practice—there are variants to suit all levels of fitness and flexibility, and there is no limit to what you can achieve. Every yoga teacher I have worked with expresses the importance of beginning where you are and letting go of outcomes and expectations—a mind-set that is also highly valuable in the voice studio.

The Alexander Technique is a method of reeducating the musculoskeletal system to improve alignment and mobility, enhance performance, and alleviate chronic tension. Alexander teachers employ verbal direction and subtle touch to encourage muscular release and deepen kinesthetic awareness. They help their students become cognizant of suboptimal habitual patterns of self-use; they facilitate an experience of more efficient movement patterns and provide tools for reinforcing them.

F. Matthias Alexander was inspired to develop this technique when he found himself in need of vocal rehabilitation. When Alexander’s nascent acting career was hampered by hoarseness and respiratory issues that were unresponsive to medical treatment, he theorized that his problems must somehow stem from his own behavior. Through self-examination and experimentation, he devised a means of identifying and supplanting the habits of posture and movement that had given rise to his vocal dysfunction. While the Alexander Technique is widely applicable to alleviating pain and improving performance, its origin as a means of vocal reeducation has earned it particularly high appreciation among actors and singers.

Body mapping, an offshoot of the Alexander Technique, was created by music educators to teach musicians to accurately visualize their anatomy in order to more effectively sense, train, and activate their biomechanics. Practitioners apply Alexander principles and methods to provide a guided tour of your functional anatomy, which therefore holds great value for singers seeking a practical understanding of how their instruments work.

The Feldenkrais Method employs movement and touch to expose limiting physical and psychological habits and restore healthy alignment, range of motion, and energetic flow. Like F. Matthias Alexander, Moshe Feldenkrais developed his technique out of personal necessity. When an injury left him unable to walk and existing medical protocols failed to help him recover, he drew on his background in physics, engineering, and martial arts to devise a means to restore his own mobility. Feldenkrais is taught in both one-on-one “Functional Integration” sessions with a certified practitioner and in group “Awareness through Movement” classes.

Singers value Feldenkrais for its application of targeted kinesthetic suggestion to retrain alignment and expand breathing. A key principle of Feldenkrais is the idea of “passive control”—initiating movement by formulating a clear intention rather than physical effort. It is therefore useful for helping singers learn to allow expressive intent to engage the singing voice, rather than muscular manipulation.

In addition to practices profiled in this chapter, there exist a wealth of mental disciplines and somatic methods that can complement and heighten your work in the studio. Explore the options available in your area, and keep in mind that finding a skilled, experienced practitioner is often of greater importance than the particular modality they espouse.

One of the things I most love about singing is that it is itself a practice that serves to integrate body and mind. Meditation, yoga, and martial arts can improve mental and physical well-being in countless ways, but these practices are most rewarding when pursued as ends unto themselves rather than as means to particular goals. Learn to approach your singing practice as its own end, and you may find that the resulting enhancement of focus, self-awareness, and expressive power serves to enrich all your activities, musical and otherwise.