Chapter 2

Boats in the Backyard

To say that Donald “Ducky” Reed has strong family ties to the Bay Shore of Oconto, the small Wisconsin city found near the bottom of the stairstep-shaped county of the same name where it meets the waters of Green Bay, would be an understatement. He can, in fact, look back to his great-great-grandparents—early settlers who arrived in Oconto in the spring of 1856 by way of steamship from Chicago.1

His great-grandfather, Louis Reed, was born in Hamburg, Germany, in 1841. In 1846, his family came to America, making the forty-two-day voyage from Hamburg to New York City in a sailing vessel.2 They settled in Chicago, where young Louis was educated in the public schools for ten years. Louis was just a teenager when his parents packed up their belongings and headed up the western shore of Lake Michigan toward what they hoped would be great opportunity at the small community of Oconto. Wisconsin had become a state only eight years before.

The Reed family was heading to a location already steeped in history. An ancient Indian burial ground considered to be the oldest cemetery in Wisconsin dating to 6,000–5,000 BC, today the location of Copper Culture State Park, is located along the Oconto River on the west side of present-day Oconto.3 Nicolas Perrot, the first French trader in the region, was said to have mediated a dispute between the Potawatomi and the Menominee near the present site of Oconto in the 1660s. During the winter of 1669–1670, French Jesuit missionary Father Claude-Jean Allouez said mass at a mixed village of Sauk, Potawatomi, Fox, and Winnebago (Ho-Chunk) on the Oconto River at the site of present-day Oconto.4 One of the first white settlers, Robert Jones, built two sawmills on the Oconto River in 1851.5 At this time only six families called Oconto their home. A June 10, 1909, retrospective in the Oconto County Reporter described the young village back in the early 1850s: “Oconto at this time, was only a woods with Indian trails running through, the main trail extending from the water mill to the mouth of the river along what is now Main Street. The Indians had their camps along this trail.”6

When the Reeds arrived at Oconto the settlement was in the midst of transforming from a pioneer outpost to a growing lumber town. The bay allowed access to the old-growth pine lands of northeastern Wisconsin and the rivers—the Peshtigo, Menominee, and Oconto—a way to get the logs to sawmills. The mills transformed what seemed like a limitless supply of raw logs into lumber to feed the insatiable demands of Chicago, which was growing at an astronomical rate. Rafts loaded with finished lumber would be towed to the mouth of the river and then loaded onto sailing vessels for transport south.7

Not long after his arrival, Louis Reed found work in a lathe mill, and he also worked as a carpenter, helping to build the first Oconto County courthouse.8 With early Oconto industry centering on the logging and lumber business, Reed readily found employment as a log driver and lumberjack. He drove for thirteen seasons, having charge of the drive for five.9

While Oconto sawmills were turning out pine lumber, the commercial fishing industry was growing, quickly becoming the town's second leading industry.

As with many men in the area, Reed worked in the woods during the winter and engaged in commercial fishing on the bay in the summer.

Turning more and more to the bay for livelihood, he began living on the South Bay Shore in the 1860s. The home Reed built on a tract of land on the shore of Green Bay south of Oconto would become a focal point for generations of Reeds to come, referred to simply as the “Big Bay House” or the “Old House” by the family.

Reed married Jane Gale, the daughter of Abram and Harriet Gale, who had moved their family to Oconto from Oshkosh in 1854. Abram had acquired a Swampland Grant from the government in 1856 that consisted of a mile and a half of Green Bay shoreline south of the Oconto River.10 Abram Gale later deeded this property to Louis and Jane, and it is probably where Louis Reed built the Big Bay House, but this is unclear.

Ducky Reed described the early Reed commercial fishing operations: “The early fishing was with sailboats and pound nets [pronounced pond nets—a stationary net held in place by stakes]. In the winter they set pound nets through the ice using horses. Whitefish and herring were the main catch back then. They would salt the fish in barrels at the fish houses to be shipped by the railroads, going to Chicago and other places. Men worked for a dollar a day and were fed at the house.”11

As Louis Reed's family grew, the house on the bay grew, too.

“Louis built additions to the house as the family grew,” said Ducky. “They had seven children. The oldest was my grandmother, Eva Reed Holmes. She died two days after giving birth to my father, Everett.”

Ducky explained how he kept the Reed family name: “My father was raised by my grandmother's sister, and he took to the name Reed, eventually having his last name of Holmes legally changed to Reed.”

Everett Reed carried on the family's commercial fishing tradition. Louis and Jane transferred the bay shore property to Everett in 1921. In 1927 he married Florence May Johnson, and a third generation of Reeds began life in the big house with the birth of Ducky (whose nickname came from the popular Disney cartoon character, Donald Duck, which debuted in 1934) in 1930.

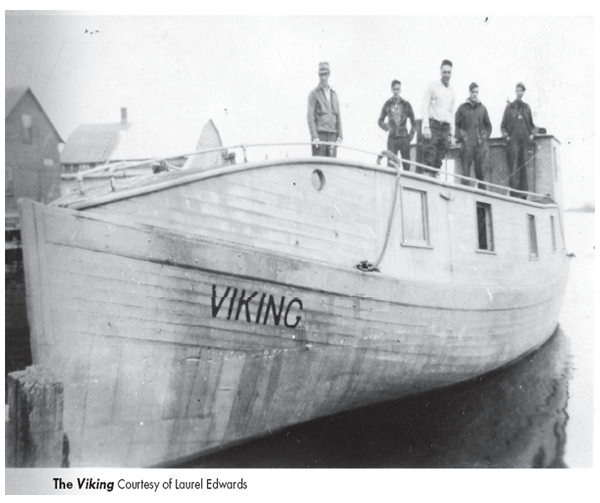

Growing up in a commercial fishing family with Green Bay in the backyard made for an interesting childhood. “My father built two fishing boats behind the house,” said Ducky. “The first was the Viking, built [in 1929] before I was born.”

The Viking, at thirty-nine feet, was typical of the wooden gill net fish “tugs” that had been developed for the Great Lakes. When the Viking was completed, it was launched directly into the bay from its perch in the maple grove on the beach in the backyard of the Big Bay House.

As commercial fishing boats transformed from the two-masted Mackinaw sailboats used in the early days to steam-powered and then diesel-powered engines, the boats took on the familiar look of Great Lakes fish tugs with enclosed decks for protection from the weather and a prominent pilot house. The gill net was the mainstay of the industry, more cost effective than pound nets and able to catch fish in deeper water.

Commercial fishing on Green Bay in the 1930s was primarily for herring, lake trout, yellow perch, and suckers—the whitefish sought in earlier days having been overfished. While the herring catch had also declined from its 1905 peak, fishing the fall herring run could still be a profitable venture. In the fall of 1930, the Viking had a record herring catch of twelve thousand pounds in one day, according to Ducky. When herring catches also began to plummet in the late 1930s beyond the point of profitability for the small operator, due in part from increasing pollution from paper mills, the Viking was relegated to dry dock and eventually sold.

A more optimistic commercial fishing outlook, particularly for yellow perch, in the early 1940s prompted Everett Reed to begin construction on a second fishing tug, the Buccaneer. While most of the new fishing tugs were being built of steel by the 1940s, the Buccaneer would be a traditional wooden boat because it was not being built in a commercial shipyard with access to metalworking and welding equipment.

Ducky remembers how his father began work on the boat after January in the winter of 1943: “The Buccaneer was built behind the house, like the Viking. Dad started cutting white oak that winter up north because around here, we have mostly red oak. He cut two-and-one-quarter-inch square strips while the wood was green, which were then soaked in a tank of hot water and bent to make the ribs. After bending them they would put them on a flat wood surface, using blocking to hold them till they were dry enough. He made them in pairs, so each pair was exactly alike for each side of the boat. He had the size of each pair of ribs drawn out on paper. The cabin was constructed by local homebuilders Hansen & Strutz. She had a sharp bow with a covering of galvanized steel up to the waterline which was needed to break ice.”

As with many of the Green Bay fishing tugs it had a twin-cylinder Kahlenberg engine in it. “The engine had built-in blowtorches to heat up the cylinders, and then compressed air would start it,” Ducky remembered.

The forty-four-foot Buccaneer hit the water in the backyard of the Big Bay House as perch fishing in the bay peaked. “In spring of 1943, the first year out, a crew of five men picked twenty-five hundred to three thousand pounds of perch a day while father had to stay in the wheelhouse to keep the boat from going over the net,” said Ducky. “At eight to ten cents a pound, my dad was able to pay off the $2,100 loan for the boat that same year in December.”

The perch boom didn't last long, and catches began to decline by 1945, just two years after the peak. “The Buccaneer was sold to fisherman Norbert Frasch from Two Rivers. It broke up on the rocks inside the breakwater there when the engine stopped during a storm,” said Ducky.

With the overall decline of the Green Bay fishery, compounded by the arrival of the sea lamprey, Everett Reed focused his business efforts on a successful mink ranch from 1946 till 1968. “When the mink were no longer profitable, my dad bought a Lake Erie steel gill net boat in 1967. He converted it into a trawler and named it the Bounty,” said Ducky.

“He trawled for alewife on Green Bay, which were sold to Art Swaer's fish meal plant, Schilling Fish, on the Pensaukee River where the Bounty was harbored. My daughter, Laurel, and I also fished with the Bounty,” said Ducky. “When the alewife were no longer plentiful on Green Bay, he took the trawler to Sheboygan and installed a lifter for gill nets and fished for chubs that winter from Sheboygan. I stayed back home and finished pelting out the remaining mink to ship to the New York auction.”

In 1979, Everett sold the Bounty to Schilling Fish in Pensaukee. Owner Art Swaer changed the boat's name to Art Swaer IV and continued trawling for alewife there until he gave the boat to longtime employee John Kulpa, who converted it back to a gill net boat. Kulpa still fishes perch with it from the Pensaukee River.12

Everett passed away at the age of eighty-six in 1990 and his wife, Florence, in 1994, leaving the Big Bay House to their children, Ducky and Janice.

Today, Ducky Reed's only daughter, Laurel Edwards, and her family occupy the Big Bay House—and Laurel's daughter, Megan, represents the fifth generation of Reed descendents to have lived there. Ducky lives in a small house next door to the old house. The large picture window in the living room of Ducky's home frames a scene of beach and Green Bay open water that one could imagine has changed little since 1856 when the steamship carrying sixteen-year-old Louis Reed passed the spot on its way to his new home.