Chapter 6

Carl Marty's Northernaire: A Special Place in Time

It was one of those quirky, rare moments when the convergence of the right place and the right time coalesce into an indelible memory.

I was a senior in high school at the time, and it was the week between Christmas and New Year's. It also was the late 1970s, and cross-country skiing fever had consumed, if not the nation, at least the Upper Midwest. This was the reason behind my parents and I heading north to Eagle River to meet my sister and her family for a long weekend of both skiing and learning how to ski at one of the area resorts.

After a day of the “learning how” part, my parents were ready to move on to something a little less strenuous, something they already knew how to do, and something they were pretty good at—sightseeing, shopping, and eating out.

On this day they had a destination in mind: someplace called the Northernaire. As I pieced together the story during the drive to Three Lakes, in northeast Oneida County, I learned that this Northernaire was nothing short of the “Waldorf of the Wilderness”—a golden, gleaming resort complete with luxury guest rooms, gourmet chefs, a grand ballroom, entertainment that rivaled Las Vegas, and celebrities rubbing elbows with the tourists in the hallways.

My parents had eaten dinner at the Northernaire many years before and had apparently soaked in enough of the grand ambience and aura of the place to create larger-than-life memories that they still held as we pulled into the parking lot that winter afternoon in 1978.

Our car was about the only one in the parking lot. The theme of emptiness continued as we entered the resort and then the well-windowed dining room. Although it was a still a prize week for northern tourism, the Northernaire was quiet, with none of the hustle and bustle you'd expect of a famous northwoods resort. There were no celebrities to rub elbows with. In fact, aside from resort staff, it seemed as if there was no one else in the entire place.

We were seated for lunch in the big dining room, the only people there except for a lone old man sitting at the opposite end of the room. I had noticed him immediately, his presence in the mostly empty dining room conspicuous.

After we ate lunch and my dad paid the bill, the waitress handed me a small paperback book. “Mr. Marty would like you to have this,” she said. The book was Mr. Conservation: Carl Marty and His Forest Orphans, written by August Derleth, the prolific Wisconsin writer from Sauk City. It was inscribed: “With Best Wishes! Carl Marty.”

Then the waitress offered us an invitation on behalf of Mr. Marty to watch some wildlife films. Strange as it may have seemed to me—unfamiliar with Carl Marty or any of the Northernaire's history aside from what my parents had discussed on the short trip from Eagle River to Three Lakes—I immediately said “yes,” hoping my parents would agree.

They did, and we were led to a downstairs room where we found the old man I had seen in the dining room, Carl O. Marty Jr. himself, the founder and proprietor of the Northernaire. At that time Marty was nearly eighty years old.

For more than an hour we watched reels of wildlife movies featuring the Northernaire, Marty, and a cast of woodland animals including two otters known as “Sugar and Spice,” a beaver named “Bopper,” and a porcupine that went by the name of “Ouch.”

I didn't realize until many years later that at the time I was experiencing a unique slice of north Wisconsin history as well as playing witness to the end of a special chapter of the northern Wisconsin resort industry.

After learning more about Carl Marty and his vision of a resort unlike any the north had ever seen, I realized that the Northernaire of my parents' memories truly had been something special. But that special place, the reality of the Northernaire as the Waldorf of the Wilderness, existed in a different time—its time the ‘40s, ‘50s, and ‘60s—and by 1978 that time was fairly well past.

Marty was a Wisconsin resort visionary. Born in Monroe, the Swiss cheese capital of the United States, in Green County at the turn of the century, but growing up in Chicago after his father took a job there when Carl was eight, Marty demonstrated his skill in the business world at an early age.1 In his early twenties he founded “Carl Marty and Company,” which specialized in cheese production. Other successful cheese operations, all based in Monroe, followed.2 By the late 1930s Marty's operations had the attention of milk and cheese giant Borden, which bought him out in 1939.3

With money in the bank, Carl Jr., with help from his younger brother Bob, decided to act upon a dream he had of developing the perfect luxury resort.

“The dreaming we had indulged in before, now had to be transferred into practical, business-like plans,” Marty wrote in the August 1947 issue of Resort Management. “Over a period of time, we had become more and more convinced that there was a definite need in our state of Wisconsin for an all year ‘round resort.”4

Marty knew precisely the type of customer he was after: the more affluent post-war veterans and their baby boomer children. What he would do would be a departure from tradition. He realized that while people desired “new surroundings” for recreation they “would also desire the same comforts, conveniences and luxuries of their town life.”5

“The people to whom we would appeal, then, would be that class having the time, income and inclination for this kind of resort,” wrote Marty. “And in this group are many families with children—youngsters, and young men and women in college and out of school who possess all the vitality and energy of youth accustomed to rigorous activities and sport.”6

Marty would place his luxury resort in the heart of the northwoods, “where those who seek the outdoors' life and those who wish rest and relaxation may find all this and more among beautiful surroundings and with well-appointed accommodations and efficient service.”7

Carl Marty Sr. had purchased land on Deer Lake near Three Lakes in 1915 and had built a vacation cottage on it.8 This area would become the site for Carl Jr.'s dream.

The construction of the Northernaire began in 1946, with the resort formally opening in 1947. The Show Boat night club, which originated as a clubhouse for an existing golf course purchased by the Marty brothers, had already been built and opened in July of 1940. A unique set of circumstances led to the building of Northernaire lore well before the construction of the resort itself.

Professional baseball player Fred “Cy” Williams, who played for the Chicago Cubs and the Philadelphia Phillies during his nineteen-year career from 1912 through the 1920s, had made Three Lakes his permanent home. A capable outfielder, Williams was best known as a home run hitter (the first major leaguer to hit two hundred home runs in his career).

Williams, however, had other talents besides baseball. Before starting with the Cubs he had graduated from Notre Dame with a degree in architecture.9 When his baseball career had run its course he returned to Three Lakes to begin a successful career in architecture and building. It was natural for Williams to design and build the Northernaire.

Marty's timing for a new kind of northwoods resort could not have been better. Oneida County and other north Wisconsin resort destinations were poised for exceptional growth in the post-war era. In March of 1946 the Rhinelander Daily News reported: “All indications here point to the brightest tourist season in Rhinelander's history. Behind the giant wave of optimism sweeping the county's resort men and the Chamber of Commerce is the flood of mail that is engulfing them from the southern part of the state, Illinois and Indiana asking for reservations.”10

Herman Bostrom, a Rhinelander-area real estate agent and resort owner, offered the Daily News his reasoning for the expected influx of tourists: “What makes the tourist prospects rosy, in Bostrom's opinion, is the bulging wallets of the people coupled with a strong yen for relaxation after four years of war and rationing.”11

The bulging wallet was a key to the future of the Northernaire. If the resort was to supply unparalleled amenities in the northwoods there would be a cost. “This, plus the resort being an all year ‘round place, naturally resulted in a cost much higher than average,” wrote Marty. “Rates, therefore, had to be keyed commensurate with cost and conveniences offered.”12

Whether it was pure business savvy, some unexplained intuition, or a little of both, the Marty brothers had hit the mark when determining the clientele they wanted to attract to the Northernaire.

The Waldorf of the Wilderness quickly attracted celebrities as well as well-heeled tourists. In July of 1947 Gypsy Rose Lee, the famous burlesque stripper, actress, and writer, made her second visit to the Northernaire.

“Miss Gypsy Rose Lee, who is vacationing at Marty's near Three Lakes,” reported the Rhinelander Daily News, “last night showed personal movies to a group of friends and their guests in the Hotel Northernaire and later was presented to guests in Marty's Show Boat.”13

Lee was an ardent angler: “Miss Lee's personal movies last night showed her fishing expedition last summer near Three Lakes and illustrated in one easy lesson how muskies were landed.”

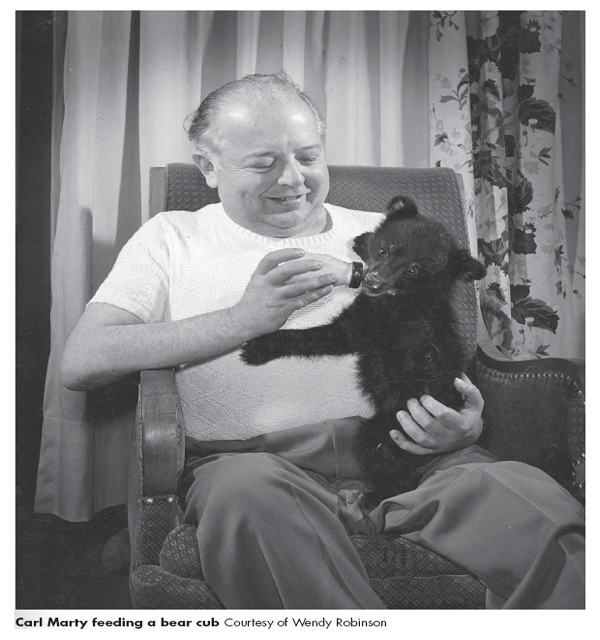

Perhaps more important in the lore and legend, and the fame, of the Northernaire—more than its celebrities and world-class chefs, more than its luxurious amenities and big-city entertainment—were Carl Marty's adopted woodland animals.

“People come here from all over the United States to spend their vacation time among the forests and waters of this magnificent north country. Many are not aware of Carl Marty's fame as a naturalist and are astonished to find small, wild animal orphans wandering at will around the grounds of this luxurious resort,” wrote Edith Lassen Johnson in her book about Marty's wild orphans, Mother Is a Saint Bernard 14

While walking on the Deer Lake property prior to the construction of the resort, Marty and his cocker spaniel Rusty had a brief close encounter with a wild red fox.15 The incident inspired Marty to experiment with taming wild animals and letting them interact with his domestic pets. Marty started with red fox pups, taming them enough so that they bonded with Rusty. As they grew, the fox were given the freedom to come and go as they pleased, but they seemed to retain an affinity for the spaniel and returned from the woods on numerous visits.

The experience with the fox seemed to rekindle Marty's youthful love of wildlife, and wild animals became a central focus during his reign at the Northernaire. The fox experiment led to deer fawns and eventually to beaver, porcupines, pine marten, and coyotes—just about any orphaned or injured wild animal that was brought to the Northernaire.

Ginger, a daughter of Rusty, along with a St. Bernard named Bernese became famous as the dogs that not only bonded with the wild orphans but mothered, protected, and formed lasting relationships with them.

In a self-published book, Northernaire's Ginger and Her Woodland Orphans, Marty writes about building a small house for Ginger:

It was quite evident that Ginger needed a house of her own in which to receive all her woodland friends who come to call. So we had a house built for Ginger with her name on the door, and it has proved to be a popular place for the animals to congregate.

A sign welcomes all animals and says that if the door is closed, to come in through the hole in the floor.

During the summer months especially, Ginger naps heavily during the day because most of her friends come to call at night, and she is kept busy playing the perfect hostess to all!16

The Northernaire's menagerie of free-roaming wild animals, as well as the celebrity status of Rusty, Ginger, and Bernese, may have done as much to lure tourists to the resort as the scenery, celebrities, and hotel amenities.

Alvin E. O'Konski, a Republican congressman who represented Wisconsin's old tenth district (which covered much of northwestern Wisconsin) was so taken by Marty's wild animal menagerie following visits to the resort that he presented a speech about Marty before the second session of the Ninetieth Congress, subsequently printed in the Congressional Record.

In reference to the federal government's spending millions “to find out why rats, mice, and monkeys act the way they do,” O'Konski stated:

“For the past 25 years in northern Wisconsin, at no expense to the government, a great humanitarian and a great savior of wildlife has been carrying on exactly such an experiment with no cost to the taxpayers. He has learned why wild animals act the way they do. He has discovered a way of getting the animals of the forest to accept each other, to live with each other, and to love each other.”17

With a protectionist outlook on wild animals, Carl Marty was not the best friend of the local hunters and trappers. Some of his friends included Cleveland Amory and Sterling North, noted antihunting and antitrapping figures. But they also included outdoorsmen-writers—such as nationally known Sigurd Olson and local Walt Goldsworthy—as well as Rhinelander-area woodsman and trapper Paul Munninghoff.

Goldsworthy's widow, Doris, told me that Marty was vehemently opposed to trapping and angered local residents with his push to establish no-hunting and no-trapping refuge areas around Three Lakes. “He didn't like the idea that animals such as beaver could be trapped when the kits were in the den,” she said.18

The Northernaire as a business entity, however, was not by any means against animal use.

The first issue of Northernaire and Showboat News, a promotional newsletter, stated: “There is a 2,700 acre tract of wild land with a trout stream running through it for guests who want to fish or hunt.”19

Aside from all of the many activities the Northernaire offered, fishing was still important to many of the guests.

“A 49 inch Muskie was caught off the Show Boat dock. No, we can't guarantee that you will land one this big. Yes, there are even larger ones in our lakes. It's a challenge!”20

Marty died at the age of eighty in 1979, a year after my parents and I joined him for wildlife films that winter day.

After Marty died, the resort passed through a series of owners, including Fred Schlagel, who worked to keep the hotel's reputation for world-class entertainment alive.

“A near sell-out crowd is expected to pack the Northernaire in Three Lakes this Saturday, August 13, for the performance of internationally known comedian Bob Hope,” reported The Three Lakes News in 1983.21

Bob Hope's appearance on that sweltering August night may have marked the end of the grand resort's attempt to retain the glory of years past. The rest of the world, or at least the northwoods resort industry, was catching up to Carl Marty's vision, and by the late ‘80s and early ‘90s fancy new resorts and condominium developments were appearing on a regular basis on prime northern lakes.

The Northernaire was still in operation, but just barely it seemed, when my wife and I stopped there in the summer of 1990. We had just moved to Rhinelander, and my own memory of the Northernaire and Carl Marty on that odd winter day in 1978 prompted me to take her there one Saturday afternoon. We had hoped to eat lunch there in the big dining room but were informed that the Northernaire no longer offered lunch, just dinner.

Soon after, the grand northwoods resort was closed due to bankruptcy and stood silent and vacant overlooking Deer Lake.

In December of 1995 a corporate partnership, BarKat LLC, based in Milwaukee, purchased the property at a sheriff's foreclosure sale for $625,000.22 The plan was to raze the old Northernaire and build an expansive new condominium development on the 1,800 feet of prime lakeshore property.

“A new lodging and restaurant complex may rise like the phoenix from the ruins of the withering old Northernaire in Three Lakes,” reported Tom Michele of the Rhinelander Daily News.23

Carl Marty's dream vanished from the face of the earth as the Wisconsin northwoods eased toward summer. “The landmark Northernaire Hotel, once called the ‘Waldorf of the Wilderness,' is scheduled for demolition next week, with the new owners of the property planning to build a new hotel with condominium units to replace the present structure,” reported the Rhinelander Daily News in May of 1996.24

BarKat's project never materialized. After facing years of stiff opposition from local residents and landowners concerned about the size of the proposed project and possible negative impacts to the lakes, as well as the inability to gain approval from the county, BarKat abandoned the project.25 Eventually an Eau Claire-based development group purchased the property.26

With new owners toting a scaled-down development plan, the phoenix did rise from the ruins of Marty's Waldorf in 2007.

“Sixty years after the original hotel and vacation complex was built, the Northernaire lives again,” reported the Rhinelander Daily News in August.27

But the resort complex, now called the Northernaire Resort and Spa—which officially opened when the secretary of the Wisconsin Department of Tourism and a state senator snipped a ribbon in front of the entrance doors on an August day twenty-four years after Bob Hope entertained 3,500 people under the Northernaire's big tent and long after Rusty and Bernese walked the grounds—resembled the old resort in name only.

The original Northernaire, the product of Carl Marty's vision, had once occupied a special place in time and possessed a certain style and a unique grace that will never be duplicated.