Chapter 13

Waterfowl Hunting with Live Decoys

The severe drought that much of America experienced in the early 1930s was a major factor in the agricultural disaster of the dust bowl and was also devastating to waterfowl populations as once-productive wetlands dried up. Plummeting duck numbers led to more restrictive hunting regulations. One common practice of both the market and recreational waterfowl hunter that was regulated out of existence in 1935 was the use of live decoys.

The use of live decoys in waterfowling was a practice brought to America by European colonists. The use of “stool birds” to lure an unsuspecting flock to the gun was certainly used by early colonists, but the method gained in popularity as large-scale market hunting developed in the East and Midwest after the Civil War.1

On the East Coast live decoys were used primarily in goose hunting. The Outdoor Life book The Story of American Hunting and Firearms described the use of live decoys for goose hunting on the sand spits of bays around Long Island:

A decoy rig consisted of between fifteen and forty geese of both sexes, taken to the spit in coops. Stakes were driven into the sand at regular intervals and a bird was tethered to each stake by a leather leg strap or hobble. The most valuable member of the rig (worth up to two hundred dollars) was a trained gander tethered some distance from the other birds, so that its calls would attract wild geese passing overhead.

…[T]he art of decoying geese reached its height of deadly efficiency along the New England coast, where the stool birds were trained—with corn and endless patience—to fly out to meet flocks of wild kin and lure them to the blinds.2

In Wisconsin and other Midwestern states live decoys were used for both goose and duck hunting during the late 1800s up to 1935. Many sportsmen kept a collection of mallards to be used as “live callers.” While a hunter would still have a set of artificial decoys or “blocks” to provide the visual enticement, the primary purpose of the live duck was for calling.

The Wisconsin outdoor writer Gordon MacQuarrie, who wrote in the 1930s and ‘40s, immortalized the use of live decoys in his story “Minnie the Moocher,” a tale of a pair of mallards he collected at a farm near Frederic, Wisconsin, to be used as live decoys for waterfowling. The pair, Minnie and Bill, were quite the characters. Min became a deadly caller to every passing male mallard. Bill was known for growling.3

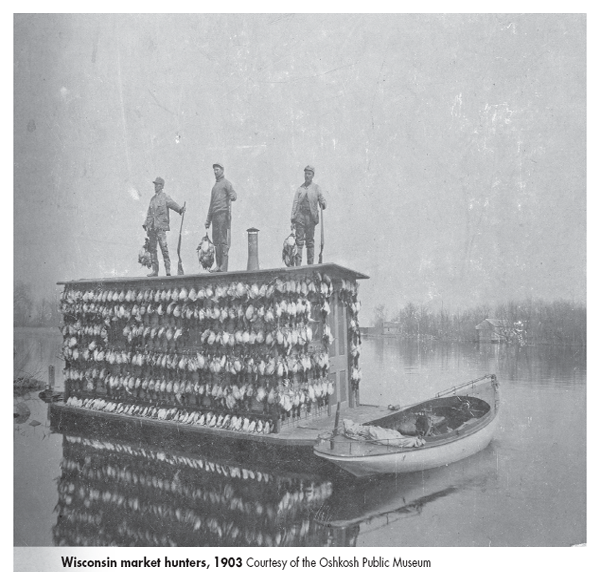

MacQuarrie's story offers a glimpse into the days when live decoys were allowed in duck and goose hunting. Measured by the sporting standards of today, the use of live decoys, which could be extremely effective, may seem unsportsmanlike. When utilized by market hunters in combination with other methods such as baiting, punt guns, and sink boats to take hundreds and sometimes thousands of birds a day, the practice was indeed unfair. However, for ethical sportsmen such as MacQuarrie and many others, live decoys were an accepted tool prior to 1935.

As with MacQuarrie's Min, the mallard hen was most popular for duck hunting, while both male and female geese worked equally well as goose callers.

Sportsmen at that time cared for their live callers almost as much as they cared for their hunting dogs. A good caller might be sold for two hundred dollars or more. According to The Story of American Hunting and Firearms: “The man who owned a drake and half a dozen Suzies often grew as fond of them as his dog, and was thrilled to watch them lure their wild relatives down to the guns.”4

In addition to MacQuarrie's story there are some other bits and pieces that record the nearly lost history of live decoys, with a great record coming from Wisconsin. Phillip S. Habermann, a noted Madison attorney who passed away at the age of eighty-nine in 2002, describes in his 1988 recollections duck hunting with live decoys in the 1920s: “Using live decoys, or call ducks as they were known, was a heartwarming experience that doubled the pleasure of hunting. The ways and means of how it was done should be preserved as part of our folklore.”5

Habermann, born in 1913, was a native of Lodi and grew up near the banks of Lake Wisconsin, an impoundment on the Wisconsin River in Columbia County. Lake Wisconsin was created the year he was born, and the lake attracted “fantastic concentrations” of ducks among the dead and half-submerged trees.

“My father was an ardent duck and goose hunter from 1895 on,” Habermann wrote. “Beginning before WWI he raised more than 100 mallards and six to ten Canada geese each year. The original stock for this flock came from wild birds that were wingshot. This flock furnished our live decoys.”

As each autumn's waterfowl season approached, Habermann and his father would scrutinize the flock and pick out the best prospects. “There was a great difference in the talkativeness of the hen ducks,” he wrote.

About half a dozen hens were chosen. Some had proved themselves the year before, while some were rookies. The chosen ducks would stay in a separate pen, except during the hunt, until the season's end.

There was a science involved in the tethering of live decoys. “To tether a live decoy while hunting it was essential to have a means of attaching a cord and weight to the duck's leg in such a manner that it would not harm the duck, and with a device that could remain in place all fall,” Habermann wrote.

A half-foot-long, thin, oiled leather strap with two slots at one end and a metal D ring at the other end was part of the rig used. “You wrapped the strap around the duck's leg, inserted the slotted end through the second slot, then threaded the D ring end through the first slot and pulled it tight. The strap was locked in place until unthreaded, but could only pull around the leg loosely.”

When hunting, the hunter attached a heavy chalk line to a five-pound weight and snapped the other end to the D ring on the duck's tether. The duck had a six- to ten-foot circle to paddle freely about. Some hunters placed little metal platforms, or stools, in the water for the live decoys to rest on.

Just as with the art involved in placing conventional decoys, there was an art to placing the live callers.

“The secret in placing the call ducks was to spot them where they could not see one another. Usually one went out front near the blocks and one back on either side of the blind. Being unable to see each other they became lonesome and talked back and forth, as well as calling loud and long at almost everything that flew past.”

Habermann also saw the similarity between the enjoyment of watching the live decoys do their job and watching a prized dog work. “Watching and listening to the decoys work was akin to the pleasure of hunting with a fine dog,” he wrote. “One never felt alone when the callers were out. You learned to understand duck talk, and could usually tell what was going on by the tone of the calls being made.”

When the practice was banned, many hunters, Habermann included, lamented the end of live decoy use. “Those days are gone forever,” he wrote. “But the memories and a few pictures remain. That era of our hunting history should never be forgotten.”

And thanks to MacQuarrie and Habermann, it won't be.