Chapter 16

The Armistice Day Storm: The Winds of Hell

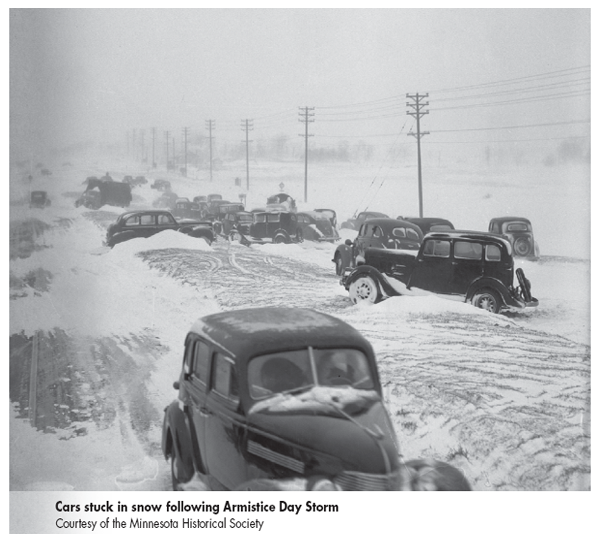

It began building nearly one thousand miles away, a classic “Panhandle hook” storm, a low-pressure system that would track from the southwest—the region east of the Rocky Mountains encompassing the Texas and Oklahoma Panhandles—toward the northeast, across Kansas and Iowa and into Minnesota and Wisconsin. As the system raced northward it gained strength by the hour—feeding on warm, moist air from the Gulf of Mexico to the south and a Canadian cold front in the north—intensifying into what meteorologists call a storm “bomb.”1 In its path houses and barns collapsed, chimneys toppled, trees were uprooted, and livestock froze to death in pastures and pens. When it reached the Upper Midwest the storm had become a deadly, raging fury—gale-force winds, plunging temperatures, rain and sleet, and then blinding snow. The big storm hit Wisconsin on the afternoon of November 11—Armistice Day. The year was 1940.

The storm moved with a terrifying swiftness that caught thousands of people, many outside to enjoy another day of mild November weather, completely unawares.

Minnesota and Wisconsin duck hunters were foremost among those people. The duck season ran sixty days that year, an increase of fifteen days from the 1939 season, and hunting prospects were good.2 Mild autumn weather, however, had hampered hunter efforts. A Wisconsin newspaper reported: “Not a lack of ducks but a lack of duck weather has resulted in a poor season to date, in the opinion of F. R. Zimmerman, in charge of waterfowl studies for the conservation department.” The report added, “The duck season may yet make up for lost time during the rest of this month with the prospect that there will be some real duck weather to put birds on the move.”3 The season was due to close November 29. Real duck weather was what hunters across Wisconsin were longing for—weather as it should be in Wisconsin in November: cold fronts and low, scudding clouds from the north that would bring down fat Canadian birds and stir up the local populations. But Armistice Day morning brought more unseasonably warm temperatures and quiet winds, another bluebird day. Hunters who ventured out to the marshes that morning had little need for heavy winter clothing; flannel shirts and canvas jackets sufficed. As the storm front approached from the west and the skies darkened in the afternoon, waterfowlers welcomed the change in weather, the increasing winds and cooling temperatures. Duck weather, finally.

Hunters from Wisconsin and Minnesota plying the vast backwaters, marshes, and wooded islands of the upper Mississippi River roughly between La Crosse, Wisconsin, and Red Wing, Minnesota, were the first to feel the change. As the barometric pressure plummeted to record-setting lows, the ducks responded accordingly.

“There were just a lot of birds moving,” recalled Minnesota hunter Sonny Ehlers. “Ducks, there were ducks all over.”4

But the excitement over the arrival of duck weather was short-lived. Before most hunters could react, before many could even retrieve the ducks they had just shot, the deceptively mild wind that came with the leading edge of the storm grew into a ferocious gale.

Harold Hettrick, a retired Wisconsin conservation warden, recorded his memories of the Armistice Day storm at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival on July 2, 1998. Hettrick was a high school student at the time the storm struck the Mississippi River valley:

The weather started to deteriorate. The wind came up first. And the shooting got good. Hunters were going for their limits, which were big limits in those days. They didn't pay that much attention to the ferocity of the wind until all of a sudden it was 4 o'clock. Then it was too rough to go back. That was when the hunting season closed everyday at that time, 4 o'clock. So they were stranded out there, many in hip boots and waders and small skiffs, small boats, in marshes or on shallow islands above the water line. The wind was coming over, bringing the waves over these islands and these marshes, and as 6 o'clock came it was sub-zero. They were freezing. They were sheets of ice.5

Duck hunters on the Mississippi had no way of knowing that what appeared at first to be a typical autumn weather front, like so many they had hunted in the past, would in a matter of a few hours become a howling, deadly nightmare. The intensity of the storm had not been predicted, and no warnings were issued that might have kept hunters from being trapped in the field. Apparently no one from the U.S. Weather Bureau (the precursor to the National Weather Service) was watching the storm's development on the morning of November 11.6

By late afternoon the brunt of the storm bore down on stranded duck hunters up and down the Mississippi. Temperatures that had been in the sixties and seventies in the morning plummeted to below freezing, resulting in horrendous windchill factors when combined with winds of fifty to eighty miles per hour. Evening brought heavy snowfall, blown horizontal by the gale. The night would be long and punishing for those caught in the storm.

Many of those stranded survived only through incredible effort. Hunters forced themselves to keep active during the night—running in circles or sparring with each other—knowing that to give up would mean certain death. Hunters packed marsh grass into their hip boots and waders and under their clothing for insulation. Some built nests of marsh grass underneath overturned skiffs and hunkered down for the night. One hunter survived because his hunting dogs kept him warm.7

Others weren't so fortunate. With clothing soaked from rain and sleet that came as the storm approached in the afternoon, the assault of wind, bitter cold, and snow was just too much, and hunters by the score died from exposure.

The late Wisconsin outdoor writer Gordon MacQuarrie immortalized the tragedy in a newspaper account that appeared in the Winona, Minnesota, daily newspaper November 30, 1940.

MacQuarrie described the storm as perhaps the worst hunting season disaster in U.S. history.8 He wrote about the duck hunters who died up and down the Mississippi on Armistice Day and night, caught completely unprepared for the onslaught:

The ducks came and the men died. They died underneath upturned skiffs as the blast sought them out on boggy, unprotected islands. They died trying to light fires and jumping and sparring to keep warm. They died sitting in skiffs. They died standing in river water to their hips, awaiting help.9

They will tell you this for years to come. They will recall how dad and brother were saved, and men who came through it alive together will look at each other with new understanding, as is the way with those who have seen death brush them close.10

Hunters were hit hard on the big waters of the Mississippi, but the storm didn't stop there. It continued to race eastward, gaining intensity as it swept across the state. The storm claimed another victim when it reached central Wisconsin, this time on the Big Eau Pleine reservoir, a flowage formed by the damming of the Big Eau Pleine River in southern Marathon County.

The Wausau Daily Record-Herald reported: “Enrollees of CCC Camp Rib Mountain and individual searching parties were patrolling the banks of the Big Eau Pleine river reservoir in the town of Green Valley today in an effort to locate Harry Zastrow, 57, town of Hamburg farmer, who was believed to have been drowned when a sudden squall struck the reservoir shortly after he started out alone on a duck hunting trip in a boat Monday noon at 12:30 o'clock.”11

Zastrow, his son LeRoy, and a farm hand, David Smith, had set out on a duck hunt before noon on Armistice Day, probably encouraged by the change in weather and hoping that the winds would bring ducks on the wing. After meeting at a local farmer's boat landing on the shores of the flowage, LeRoy and Smith rowed their boat eastward, leaving behind the elder Zastrow, who planned to follow in a small skiff after a visit with the farmer.12

Zastrow “left the dock about 12:30 o'clock, just before the sudden squall, which whipped waves into heights of four and five feet on the treacherous waters, struck the spot.”13

The storm forced LeRoy Zastrow and Smith to beach their boat and walk back several miles to the dock, their agreed-upon meeting place. The squall was so severe, LeRoy later told the Wausau reporter, that he “abandoned decoys only 20 feet from his boat.”14

The search party finally discovered Harry Zastrow's body on an island in the reservoir. Apparently he was able to beach the boat safely but succumbed to exposure.15

Those duck hunters plying the larger waters of the state, such as the Mississippi and the large flowages and lakes, were most vulnerable to the storm's fury. When the winds and cold tore through the popular duck hunting marshes of the Poygan, Butte des Mortes, and Winnebago lake chain in southeast Wisconsin, havoc, suffering, and death again ensued.

“An example of the wind's force was found in reports from Fond du Lac, at the foot of Lake Winnebago, and Neenah, at the head of the lake, 40 miles north,” reported the Associated Press. “At Fond du Lac one could walk 500 to 600 feet out into what ordinarily was the lake, and not get wet feet—the wind had pushed water that far from the normal shoreline.”16

Without the benefit of advanced storm warning and communication systems, group after group of waterfowlers were caught by the storm, including dozens hunting Lake Winnebago and Lake Butte des Mortes. As Gordon MacQuarrie had done for the Mississippi River hunters, reporters in southeastern Wisconsin documented the individual life-and-death struggles that played out against a backdrop of gale-force winds, whitecapped waves, and blinding snow.

The Associated Press reported numerous harrowing tales of survival:

“Walter Haufe, 28, Neenah was rescued from the lake [Winnebago] after his skiff swamped. He stood in water up to his armpits for an hour and a half before he was noticed by the caretaker of a nearby estate.”17

“R. J. White, Oshkosh banker, Walter Kieckhefer, Milwaukee, and William H. Brand, Milwaukee, had to spend the night on Long Point island in Lake Winnebago because the water was too rough to permit rescue. A campfire burned on the island throughout the hours of darkness.”18

Carl Hartman, Milwaukee, was rescued from a marsh on Butte des Mortes, but suffered frostbite on feet and hands.19 In a Wisconsin Sportsman article published in 1974, writer Lee Brunner documented the survival story of an individual duck hunter, Bill Davis of Oshkosh.

Davis had decided to spend Armistice Day afternoon hunting the familiar waters of Lake Butte des Mortes. Not long after he had rowed his skiff more than a mile and settled it into a marshland blind, the weather began to turn.

“As he waited he could feel the air growing colder,” wrote Brunner. “Winds picking up too, he [Davis] thought. If these waves get any higher the decoys will be nosing in. He waited a short time to see if the wind would calm down, then reluctantly began picking up his decoys.”20 Other hunters in the area were doing the same. But the storm was moving faster than the hunters.

Brunner wrote that Davis barely escaped with his life that day. As he tried to get to shore, freezing rain and wind-whipped waves threatened to swamp his skiff. Only through sheer determination was Davis, clothing coated with ice, able to reach a small cabin where he hoped a friend would be present. At the cabin door he was too cold and exhausted to knock, but he managed to kick lamely with his foot. His friend was there, and his life was saved.21

The survivors were the fortunate ones.

“Tales of thrilling rescue and harrowing experiences were told as dozens of duck hunters were brought from lakes and marshes,” reported the Associated Press. “Not all of them returned. Some drowned and some died of exposure as the 60-mile wind whipped usually placid waters to a froth. Several of those saved suffered frozen hands and feet.”22

One of those who lost his life on Butte des Mortes was twenty-eight-year-old Oshkosh native Lawrence Boeder.

“Boeder, who with his brothers, George and Paul, went hunting on Lake Butte des Morts [sic], froze to death when raging winds brought near zero temperatures to this region during the night. The party had been trapped on an island by high waves. Paul Boeder was treated for frozen hands and feet.”23

Neal Lendved, eighty-seven, currently a resident of Green Bay but born and raised in Kewaunee, first started duck hunting as a kid in the 1930s, mentored by his father, an avid duck hunter. He was eighteen years old when he and his father decided to venture out to a local duck lake the day after Armistice Day. On the southeast side of the state the storm's winds hadn't really peaked in the area until during the night, and they were still high in the morning. Awaking to what seemed like great duck weather on November 12, the Lendveds headed to East Alaska Lake with high expectations.

“The expedition started late that morning,” recalled Lendved sixty-nine years later:

A sudden drop in temperature and gale force west wind promised good hunting. We went to East Alaska Lake, not too far from home. Using a rental boat from a livery on the west shore we headed for a small cattail island near the lake's middle. As soon as we left the shelter of the west shore it became evident that the heavy wind would not allow us to row back to the landing. There was no choice. We headed for the island.

We didn't see many ducks until the blasting wind blew us into the reeds of the island. It seemed that every duck of every kind was sheltering in those cattails. As they went out we gave them a shotgun salute. A couple of birds fell, but they were not the ones we were aiming at. The wind was so strong that the shot was blown down wind and the birds, although flying full out, only made slow progress in the wind.24

Because the gale would not allow Lendved and his father to row back to the boat livery, they set a course downwind and landed on the northeast shore at the farm of a friend of the elder Lendved.

“It then became my chore to walk back to the landing, make my apologies to the boat owner, retrieve our car, and pick up my dad at the farm house,” remembered Neal.

At only about fifty acres in size, East Alaska Lake did not present the same challenges and dangers hunters experienced on the bigger rivers, lakes, and flowages in the midst of the storm, and the Lendveds' experience there was not enough to keep them from the field.

“Since we were slow learners,” recalled Neal, “we simply went back to our home, put on drier and warmer clothes and went to a blind we had under the sheltering bluffs of Lake Michigan. The idea was that we would only shoot birds under the wind shadow of the bluff. I would retrieve them with our fourteen foot skiff.”

The hunters' plan worked well at first, until one downed bird caught the wind and landed outside of the bluff's wind shadow. Attempting to retrieve the bird, Lendved's skiff also caught the wind, which threatened to take it out to the open waters of Lake Michigan. Lendved recalled:

Recovering the dead bird lost all priority. Rowing into the wind was a losing proposition, but by pulling full out and veering to the north I hoped to come across a reef that extends straight out from the shore. By heading west northwest my actual course was east northeast. After about fifteen minutes the breaking waves told me I was over the reef and an oar over the side sounded about three feet of water. So it was over the side and a long cold wading exercise. My father met me half way to shore and we pulled the boat back to shore. That ended our hunt for the day.

Neal Lendved came very close to becoming an addition to the Armistice Day storm death toll. “The fool killer was disappointed that day,” Lendved joked.

On land the storm reached its greatest intensity in southeast Wisconsin. In the Milwaukee area, the temperature had dropped an incredible forty-one degrees in twelve hours. A warm fifty-seven degrees on Armistice Day morning had plummeted to sixteen degrees by 11:00 p.m. and continued to drop to thirteen degrees during the night. Winds reaching eighty miles per hour were recorded at the Milwaukee airport.

Coast guardsmen recovered the body of Edward Quick, Milwaukee, from Big Muskego Lake, located in Waukesha County southwest of Milwaukee. In an Associated Press story, two other Milwaukee hunters whose boat had frozen into the ice on Big Muskego Lake during the storm described how they witnessed Quick's plight:

“‘About 30 feet from us was another man in a rowboat,’ Ignatius Zielinski said. ‘He didn't have any gloves on. He'd row a few strokes and then huddle up. Every once in a while he'd lift his arms, palm forward up over his shoulders toward the sun. Then he slumped over the side of the boat. Both arms dangled in the water.’”25

Leaving Wisconsin behind, the storm howled out across the open waters of Lake Michigan where it caused havoc with shipping lanes, grounding and sinking ships and sending hundreds scrambling for safe harbor.

Early in the storm's development, winds were from the southeast, which caused many ships on Lake Michigan to travel up and down the eastern shore of the lake, but when the brunt of the storm brought winds shifting to the southwest and west on November 11, ships became exposed and vulnerable to the full force of the gale and the crashing seas it created.

According to the Lake Huron Marine Lore Society, “While the gale was violent on Lake Huron and almost as heavy on lakes Superior and Erie, it was Lake Michigan that bore the brunt of a storm of incredible character and the longest in duration known to that body of water.”26

An Associated Press report from Ludington, Michigan, on November 13 stated: “The grim tale of Lake Michigan's most disastrous storm in recent years unfolded slowly today as coast guardsmen, aided by subsiding seas, renewed efforts to reach stricken vessels being dashed to pieces on the rocks.”27

The William B. Davock was one of two ships lost. The Davock sank in 210 feet of water off Pentwater, Michigan, taking with her all thirty-two men aboard and a cargo of coal.28 The Canadian grain carrier Anna C. Minch was the second freighter completely destroyed during the storm, also going down near Pentwater and taking with her the entire crew of twenty-four.

The following is the text from a Michigan historical marker in Pentwater:

The most disastrous day in the history of Lake Michigan shipping was Armistice (now Veterans’) Day, November 11, 1940. With seventy-five-mile-per-hour winds and twenty-foot waves, a raging storm destroyed three ships and claimed the lives of fifty-nine seamen. Two freighters sank with all hands lost, and a third, the Novadoc, ran aground with the loss of two crew members. Bodies washed ashore throughout the day. As night fell, a heavy snow storm arrived. Rescue efforts by the Coast Guard and local citizens continued for three days after the storm. Three Pentwater fishermen were later recognized by the local community and the Canadian government for their bravery in rescuing seventeen sailors from the Novadoc.29

As the Armistice Day storm began to abate on November 13, Wisconsin residents started to tally the losses in lives and property from what had been the most horrendous storm most had ever experienced. For days afterward, family, friends, and local officials combed Wisconsin shorelines and marshes for the missing.

“Searching parties pushed forward today on the grim task of hunting more victims as Wisconsin took stock of her losses in the death-dealing gale of Monday and Tuesday,” reported the Associated Press on November 13.30

When the counting was completed, a total of 154 lives lost were attributed to the Armistice Day storm.31 Minnesota suffered the heaviest toll with forty-nine dead; about half of those were duck hunters.32 Thirteen Wisconsin deaths were attributed to the storm, many of those duck hunters as well. Another fifty-nine deaths were related to the shipping disasters on Lake Michigan.33

For years afterward, old duck hunters told stories of the Armistice Day storm—tales of courage, survival, and death.