Chapter 20

Murder at Pelican Lake

Hunters and trappers spend a great deal of time alone in the woods, and outdoor activities in remote areas have their share of inherent dangers. In the early 1930s, the Wisconsin northwoods held extra dangers, with large tracts of remote, logged-over country, limited communications, and few heavily traveled roads along with occasional gangsters, moonshiners, and poachers.

Edward Keeler didn't worry about dangers in the woods. The son of the first white settlers in the township of Enterprise, Oneida County, Keeler had grown up in wild, sparsely settled places. An accomplished fur trapper, hunter, and fishing guide, he was a rugged man who was at home in the woods. He had no reason to believe that another routine trip to his trapping shack in early December 1931 would be his last.

Born in 1871 in Sand Lake, Michigan, Keeler accompanied his family to the Green Bay area in 1878 and then to Enterprise in 1888 after his father inquired in Antigo about good land to homestead. Edward was seventeen years old when his family made its way to Enterprise.1 The young Keeler developed a deep and passionate love for the northern Wisconsin outdoors at a time when many saw the northwoods only as a resource to be exploited. At the time of the Keeler family's move to Enterprise many Native Americans lived in the area, and Edward learned much about hunting, trapping, and tracking from them. He eventually became a well-known woodsman in the area as well as a highly respected citizen.

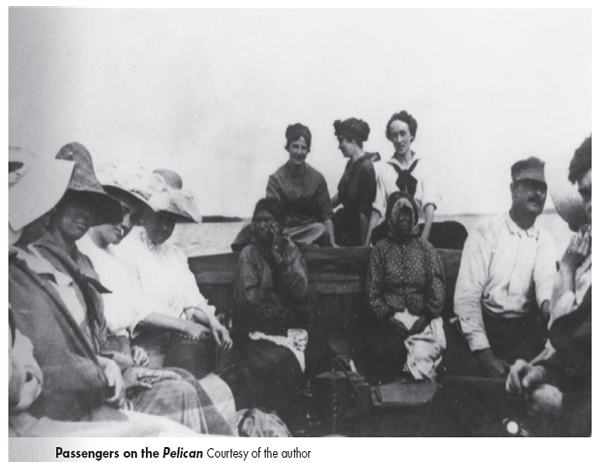

Edward's father, George Keeler, owned and operated a resort on Pelican Lake, near Enterprise, and Edward served as a fishing guide on the lake for many years.2 The resourceful Keeler owned and operated a forty-person motorized boat on Pelican Lake during the tourist season. With his boat, the Pelican, Keeler picked up tourists from the railroad depot in the little village of Pelican, situated on the eastern shore of Pelican Lake, and transported them to the many resorts on the large lake and gave boat tours as well. He also delivered mail, fresh dairy products, bakery goods, and produce to the resorts. Keeler's beautifully designed and constructed boat, which sported an inboard motor, was the pride of Pelican Lake.

During the winter, Keeler earned money by running a furbearer trapline. He eventually built a small trapping shack back in the woods about three miles north of his home. In his later years he retired from the passenger boat service and began spending more time in pursuit of hunting, fishing, and trapping ventures. It was typical for Keeler to pack a few days' worth of supplies and head out to the shack to run his trapline, hunt, or just explore the woods and swamps.

On Thursday, December 3, 1931, Keeler, sixty years old at the time, left home for a two-day trip to the cabin. He told his family he would be home by Saturday. When Keeler failed to return as expected, family members became concerned—it wasn't like him to change plans without letting someone know.3 Keeler's son, Edwin, went to the cabin looking for his father and discovered that Edward had dropped off the supplies, but the water and food were frozen. It looked as though no one had been in the cabin for a day or two. A search of the area by Edwin on Saturday, hampered by fresh snow that had covered any tracks, yielded no clues to the whereabouts of his father.4

Another unsuccessful search for Keeler was conducted that Sunday. The next day, county officials organized a search posse of more than fifty men led by Oneida County sheriff Hans Rodd. The posse scoured the woods in the vicinity of the shack. During the search, the body of Edward Keeler was found by his brother, Clifton Keeler, facedown in the snow in a pool of frozen blood.5

Sheriff Rodd pieced together what had happened by examining the clues at the scene. The sheriff's conclusion about Keeler's last minutes was gruesome. Apparently, Keeler had been walking along with his pack on his back, probably believing he was quite alone in the December woods. From about fifty yards away, an unknown person fired a .30–30 rifle at Keeler, a single shot striking him in the abdomen.6

The shooter would have been hidden by brush, and according to reports the single bullet passed through a two-inch-diameter tamarack tree before hitting Keeler. There was no evidence that the shooter did anything more than continue on his way, even though Keeler did not die instantly and probably was able to cry out, according to the sheriff.7

The mortally wounded man was able to stumble to a nearby stump, where he sat down to rest. He never got up. Bleeding from the wound, he eventually slumped forward into the snow and bled to death. The deputy county coroner from Rhinelander estimated that Keeler had been dead for at least two days prior to the discovery of the body. Because snow covered his body, officials knew he had been shot sometime before Saturday evening.8

The death of Edward Keeler presented a real mystery for officials. Two theories were offered as possible explanations for the shooting. The official theory was that Keeler was mistaken for a deer by a game violator who shot at movement or sound through the brush and then in a cowardly manner skipped out when realizing a man was shot.

“Although Sheriff Hans Rodd and Deputy Coroner Rudolph Carlson were still continuing their investigation this afternoon,” reported the Rhinelander Daily News on December 7, 1931, “it is believed Oneida county officers probing the death of Edward Keeler, Enterprise farmer, will advance the theory that he was shot and killed by a game violator who mistook him for a deer.”9

The second, less prominent theory was that Keeler was murdered in cold blood by someone bearing a grudge against the man.

Supporting the more plausible “accidental shooting by a violator” theory, both the sheriff and deputy coroner were convinced that the shooter knew he had injured a man with the reckless shot but chose to flee the scene without offering any assistance to the dying Keeler. This idea simply appalled officials and local residents.

County officials investigated the shooting further but never could discover the identity of the person who had fired the fatal shot. No one was ever arrested or charged with the crime. The town of Enterprise was rife with theories and rumors about the shooting at the time, with some holding firmly to the belief that Keeler was murdered. John Mistely, an early resident of Enterprise, now in his nineties, knew Edward Keeler well and was a member of the search party back in '31.

“Edward's death remains a mystery to this day,” Mistely said. “I guess no one will ever know what really happened.”10

Eventually most Keeler family members moved away from Enterprise and Pelican Lake, and today few people related to Edward Keeler remain. But on the west side of Pelican Lake there is a small public boat landing where a sign welcomes recreationists to the very place where Edward Keeler had regularly launched the Pelican well more than half a century ago. An interpretative sign at the landing says a few words about Edward, his father, and the history of the landing. Hundreds of modern-day sports enthusiasts today launch their own vessels at Keeler's landing, but few are aware of the mystery surrounding the brutal death of Edward Keeler.