Chapter 21

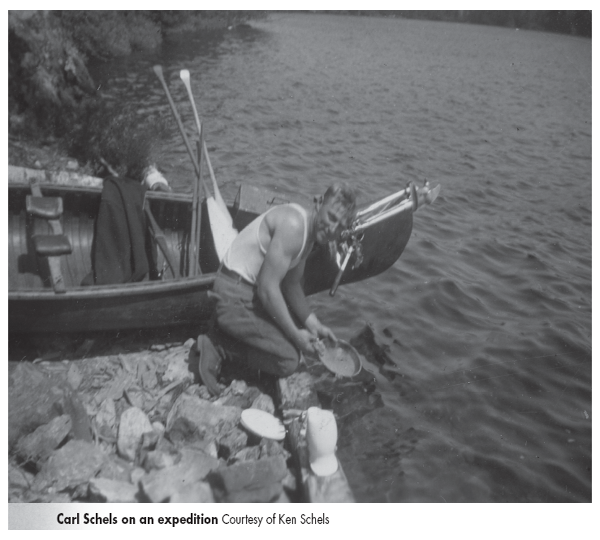

Trapping in the Blood: The Carl Schels Story

It started in late October 1929. Investors, losing confidence in the faltering U.S. economy, began unloading stocks. Panic developed and swept through Wall Street like a Kansas twister, and by mid-November the stock market had crashed, signaling the beginning of the Great Depression. In those few days fortunes were wiped out, and the prosperity of the 1920s screeched to a halt. In the months that followed hundreds of factories and mills closed their doors, and millions of American men found they were unemployed. One of those men was Carl Schels.

When the young, unmarried Schels lost his job working for Chicago Western Electric in 1930, his prospects for the future didn't look good. A Bavarian immigrant with a strong European accent and only a high school education, he had few choices. He could stand in long lines with the hundreds of other unemployed men hoping to find some menial work, or perhaps he could take to selling apples or shining shoes as some men were forced to do. He could depend on the charity of others and line up at the soup kitchens, or he could depend on the generosity of relatives. Schels chose none of those. Instead, he packed all his belongings in a Model T he had purchased for twenty dollars and drove to the Wisconsin northwoods.

“The depression was in evidence all about me and therefore, with the enthusiasm of youth, I started on my way up to the northwoods thinking that here would be my opportunity to make a fortune, little realizing that a city boy does not always find it easy to survive in the rigorous life of a woodsman,” wrote the late Schels in his autobiographical book, A Trapper's Legacy: The Tales of a Twentieth Century Trapper.1

His dream was to make a living from the land somewhere in the cutover of northern Wisconsin, where thousands of acres stripped of big timber a generation before lay abandoned to wildfire and neglect by the lumber companies. Possessing no logging, farming, or woods skills, Schels was the typical “greenhorn.” But what Schels lacked in skill he more than made up for with ambition and a willingness to work hard.

He found his way to north-central Wisconsin and took a job working on the Wolf River Mink and Fur Farm. The owner of the farm was notorious for taking advantage of Chicago boys down on their luck—working them hard before accusing them of stealing in order to get them sent back to the city without a dime of pay.2 Schels learned of the dirty tricks but wasn't one to be intimidated. He was a hard worker—clearing land with hand tools, cutting trees into firewood in the heat of July and August, and mixing endless barrels of mink feed. He worked for only room and board—oatmeal for breakfast every day and an old steel cot in the attic to sleep on. Though he knew he wasn't being treated fairly, he stuck it out, too proud to go home. The hard work made him stronger and more independent.

“The environment, responsibility and hardships I had while with the mink farmer certainly were gradually forcing me on my own,” he wrote.3

After two years at the mink farm Schels knew it was time to move on. He moved in with a neighbor, an “old-time Kentucky farmer,” to help with chores. It wasn't long before Schels had the opportunity to strike out on his own. The farmer's son-in-law owned some land on nearby Stella Lake and offered Schels a dollar a day to clear shoreline brush. The best part of the offer was that Schels could live in the twelve-by-twelve-foot shack on the property.

“This was really something,” wrote Schels, “here the first time in my life doing my own cooking, washing dishes, etc.”4

The winter of 1933–1934 would be the first on his own and when he really began to live from the land. Using money loaned by his uncle back in Chicago, Schels purchased winter supplies as well as a few leghold traps from the Montgomery Ward catalog. At the time, trapping was one of the few ways to earn hard cash in the north. According to Schels, at that time weasels brought up to fifty cents each, muskrats averaged sixty-five cents, and mink might fetch as much as seven dollars.5

“I knew practically nothing about trapping,” wrote Schels. “However if one works at it long enough once in a while you catch something.”6

Schels learned quickly, and by spring he had taken eighteen muskrats, a few weasels, and two mink. The fur was shipped to Montgomery Ward for sale.

With the hard cash made from fur trapping he ordered a Remington .25–20 from the Ward's catalog, his first real gun. “This was always considered a violators gun,” wrote Schels. “It had all the firepower needed but the main thing was it didn't make a lot of noise.”7

Due to low numbers of furbearers, trapping was highly regulated at the time, and much of Schels's fur trapping activity was illegal. However, there was a Depression-era economy in northern Wisconsin in the early '30s. Times were hard, and people did what they could—legal or illegal—to earn hard cash or put food on the table. “So, like all the violating, it would start before season opened and when one is young you are not afraid doing what I considered a little violating,” wrote Schels.8

By his second winter of trapping Schels had acquired many more traps, including the larger No. 4 Newhouse, a trap big enough for beaver. Schels's trapping skills developed quickly, but skill in avoiding the law lagged behind. “Of course I didn't know that there were other violators around,” wrote Schels. “I never saw them but they saw me.”9 Someone, probably another trapper, reported Schels to the game warden. Eventually he got caught with illegal muskrat pelts and spent twenty-seven days in the Oneida County jail as a result.

However, Schels was developing a passion for fur trapping that the law couldn't stop. To be sure, a large part of the lure was the money that could be made, but trapping was becoming something more than a simple quest for economic security. “If anything can get in your blood, it is trapping,” he wrote.10

Winter beaver trapping was illegal in those days, but it was the beaver pelts that could really bring in some hard cash. Although the big rodents were increasing in all parts of the north in the 1930s, they were still strongly protected by the state.

Beaver trapping was a game of cat and mouse between the trapper and the conservation warden, but Schels soon learned how to expertly play. As did other outlaw beaver trappers, Schels trapped deep in the forest, far from roads and towns, and stayed out in the woods for weeks at a time. “Very seldom did beaver trappers get caught.”

“At one time the warden waited twelve days for me to come out as they heard I was in there,” wrote Schels.11

The illegal beaver couldn't be sold through Montgomery Ward. “There were only a few fur buyers around dealing with illegal beaver skins so at a certain place on a certain night as many as six trappers would come with their furs to meet the buyer there,” wrote Schels.12

In 1937 Schels took his trapping to a new level. The owner of a resort in the northern Minnesota border country wilderness tempted Schels to head to northern Minnesota. There were thousands of cords of spruce pulpwood for Schels to log if he were to establish a logging camp there.

Schels headed to the wilderness with a crew of Wisconsin boys and built a small logging camp on the Gunflint Trail. The land was different from that in Wisconsin—harsh, rugged terrain and punishing weather. It was too much for the crew, and they headed back to Wisconsin, leaving Schels bankrupt and alone in the northern Minnesota wilderness.

Schels might have given up, too, if it hadn't been for his love of trapping beaver. The resort owner also was an outlaw beaver trapper, and he took Schels deep into the wilderness on a winter trapping expedition. It was an experience that almost killed him, several times.

Schels had come a long way since 1930, but trapping in the unforgiving Superior country was a new game. The trappers packed fifty miles into the wilderness, each carrying an eighty-pound pack. Shortly after Schels made a base camp, his feet and legs became painfully inflamed, the result of boots laced too tight, and he was unable to walk for days. To compound the problem he also developed snow blindness, with painful, raw eyes. He was at the mercy of his partner, who cared more about beaver pelts than he did about a helpless greenhorn. Schels tended his own ailments and began to recover.

Retreat was not in Schels's nature. Instead, he struck out on his own, an incredible decision seeing as he had no map and had never trapped the country before. He made his own camp, a thin tent held against a natural rock wall that reflected heat, with balsam boughs to cover the ground.

“When darkness of night surrounds one and you hear the sound of the wind, the trees cracking loud like a shotgun when the temperature gets down below zero, what such a small shelter against this rock wall means on nights like this cannot be counted in dollars and cents,” wrote Schels.13

When it came time to leave the wilderness with his beaver pelts, Schels again faced a life-or-death situation—he was fifty miles from his cabin and had no map, only a memory in his head of a map he had seen that showed the canoe route he needed to find.

Temperatures dropped to thirty below and colder as he walked in the direction he thought would take him home. Approaching the outlet of a lake, he fell through the ice, snowshoes on his feet and heavy pack on his back. To make matters worse, a winter storm was building. Luckily the water was shallow and he was able to chop his way to shore with a hatchet. A quickly made fire and some dry clothes saved his life. For the next two days he fought hunger, extreme cold, and weariness. Near total collapse, Schels hit the main road at about midnight of the fourth day of travel.

The Minnesota experience solidified his passion for trapping. “Trapping became the backbone of my life no matter how complicated it got,” he wrote.14

Schels returned to Wisconsin and eventually settled near Eagle River, married, and built a successful lumber business. He continued to trap throughout his life.

Carl Schels died in 1996 at the age of ninety. His book A Trapper's Legacy remains a fascinating account of his early years in northern Wisconsin.