Chapter 22

Remembering the State Fur Farm

They are gone now. Bill Osburn, Kenny Mills, the Millard brothers, and the others. The men that dedicated their lives to the operation of one of the most unique but little remembered programs of the old Wisconsin Conservation Department.

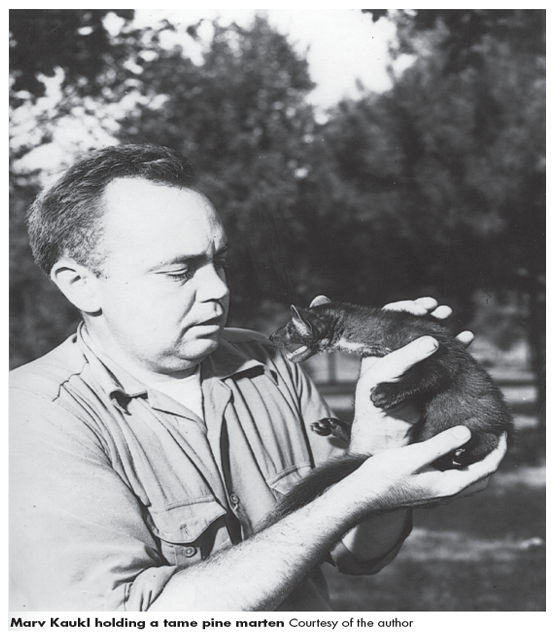

Marv “Koke” Kaukl retired from the Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources (DNR) in 1984, after forty years of service to the state. He spent his long career working at the state game farm located near Poynette, Columbia County. A year after joining the game farm staff in 1944, Kaukl was assigned to the fur plant, a section of the game farm dedicated to the propagation of native furbearers. He passed away in 2004.

“I'm the last one left,” said Kaukl with a mix of pride and sadness. “Not many people today even know about the fur program, not even those here in Poynette.”1

Today, the facility once known as the Experimental Game and Fur Farm is simply called the State Game Farm, and its focus is pheasants, producing thousands annually to be released on public hunting grounds. When Kaukl was hired, the fur farm section of the facility was a hub of activity with a variety of active projects involving furbearers including mink, fox, raccoon, muskrat, otter, and even pine marten—all part of the state's furbearer research and propagation programs.

“I started at the game farm in May 1944 and transferred to the fur farm that October,” said Kaukl. “At that time there was a genetics mink ranch, fox ranch, raccoon propagation ranch, and disease control ranch. I was in charge of the animals at the mink ranch but helped out in the other areas as well.”2

The Poynette facility was established in 1934 when Harley Mackenzie, chief of the Conservation Commission, combined the existing state game farm operations, which had primarily been located at Peninsula State Park in Door County with a satellite facility on the Waupun Prison grounds (where prisoners provided labor to hatch and rear game birds from eggs shipped from Door County), into one major facility located just outside Poynette in Columbia County. A third facility, the Moon Lake state game farm, which operated on land leased from the Milwaukee chapter of the Izaak Walton League in Fond du Lac County, continued to operate. Labor to build the new facility came from Civilian Conservation Corps (CCC) and Works Progress Administration (WPA) programs.

The fur section was an integral part of the game farm from the start. Prior to the construction of the new game farm, the conservation department had already been involved in a raccoon stocking program.

A biennial report from the State Conservation Commission stated: “The conservation department is co-operating with the Wisconsin Raccoon Hunters' Association in its raccoon stocking programs. Approximately 20 raccoons were furnished the association in each year of the biennium. A greatly enlarged raccoon stocking program is contemplated for 1933 and 1934, in co-operation with the association.”3

Although the propagation and stocking of game birds such as pheasants, Hungarian partridge, quail, and chukars was of great importance at the new facility, research into the propagation and care of furbearers, and programs to restock furbearers in the wild, were of equal importance. At the time, there was strong political and economic support to assist the fur farm industry and to provide hunters and trappers with increased opportunities to take furbearers.

Fur farming was big business in Wisconsin in the 1920s, '30s and '40s. By the 1920s, Wisconsin, along with Michigan and Minnesota, was producing half of the nation's commercial fur, and by the 1940s Wisconsin had twice as many fur farms as any other state.4 One of these farms was the large and highly successful Fromm Bros. ranch, which by the 1930s was reported to be the largest fur farming operation in the world.5 The Fromm ranch was renowned for its breeding of silver fox. In 1936 Time magazine reported: “the Fromm's have 2,000 foxes running wild on their ranch near Wausau, another 4,000 in breeding dens on a ranch near Milwaukee. The 6,000 foxes are valued at about $1,500,000.”6

The purpose of the fur farm was made clear in the 1933–1934 biennium report from the commission:

Construction began late in the biennium on the experimental fur farm at Poynette, adjoining the state game farm at that site. A modern fur plant, including laboratory, is planned.

The purpose of the fur farm [is] twofold:

(1) to produce annually for stocking from 500 to 1,000 raccoon and from 25 to 50 silver and blue foxes for experimental stocking purposes.

(2) to carry on experimental work at the farm which will consist principally in the attempted breeding and rearing of the rarer furbearing animals such as fisher, marten, and otter. Mink will be given special studies in nutrition, housing, and breeding. Some experimental work will be done with fitch. It is hoped to add a herd of karakul sheep to the fur section in the next biennium, together with an experimental project in the production of white-tailed deer from an economic standpoint.

The fur farm laboratory, which is one of the finest in the central west, will be invaluable not only to the fur farmers in the state, but to the state game farm and to commercial game breeders. It will serve in addition as a clearing house for all wild dead game shipped for analysis, particularly those species where death is caused by cyclic disturbances.

Present breeding stock at the farm includes 150 black, gray and cross raccoon; four pairs of silver fox; three pair of blue fox; two pairs of red fox; one pair of fisher; three pairs of fitch; and one pair of nutria.7

There were many disease, genetic, and nutritional problems at commercial fur farms, and research projects through the years at the game farm attempted to solve some of these, much as an agricultural experiment station. Researchers and veterinarians in the disease section worked on projects to study encephalitis in raccoons as well as distemper and rabies in mink and fox. According to Kaukl, an effective distemper vaccine was produced by veterinarians at the farm.

In other projects, fox and mink were scientifically crossed and bred to develop more valuable furs for ranchers, and artificial breeding was attempted. Some studies looked at nutritional requirements of captive animals, as fur farmers were always seeking cost-effective ways to feed their animals. A carp-feeding project looked at ways to utilize carp as mink feed.

Due in part to the influence of organized raccoon hunting groups, raccoons were a prominent feature at the fur farm in the early years. A 1935 visitors guide to the game farm explained the raccoon program: “Raccoon are being reared on a wholesale basis for distribution in the natural 'coon country,” the guide stated. “Most of the raccoon which are being released are black raccoon, which when crossed with the native gray variety, produces a superior grade of pelt. This program of release and providing favorable conditions for the natural increase of furbearers will aid many farmer boys who count upon trapping to assist them in financing themselves at school or even at home.”8

“The raccoon ranch was run by the Millard brothers,” said Kaukl. “It was a large facility. At one time I counted over four hundred female coon kept for breeding stock.”9

Raccoon hunting was extremely popular in the simpler times after the Great Depression, not just because raccoon pelts were a valuable commodity but also due to the numerous field events that could greatly increase the value of a good hound. Although raccoons were not scarce, they were not abundant, and raccoon hunter associations convinced the Conservation Commission to breed and release raccoons for sport hunters.

According to Kaukl the raccoon program was funded by sportsman dollars at first, but the funding shifted to an occupational tax of twenty-five cents per raccoon pelt sold. Eventually the funding came directly from the Wisconsin Raccoon and Fox Hunters Association.

“It was a costly program,” said Kaukl. “But it had a lot of support from an influential state senator and a newspaper editor, both involved with the 'coon and fox hunters association.”

The support was strong enough to keep the raccoon ranch running at Poynette for twenty years. When it finally shut down in the late 1950s the ranch had produced as many as one thousand animals a year for stocking. The young raccoons were crated up and distributed to wardens for release into the wild.

“A problem with the program was that the raccoon born in spring were released in August. Too young to fend for themselves I thought,” said Kaukl. “Many of us at the farm were opposed to the raccoon ranch.”10

Kaukl was involved in other interesting fur programs at the game farm, including the state's involvement in the fur trade. “Trappers working the state's portion of the Horicon Marsh had to split their take with the state,” said Kaukl. “It was a three-to-one split, with the state getting a one-fourth share of the take.” The pelts were sent to the game farm where they were graded by Kaukl and put up for auction. An old fur grader named Steve Collins taught Kaukl the art of grading furs. “Beavers were pretty good money back then,” Kaukl said. “We averaged about eighteen dollars, with blankets [large pelts] going for forty to forty-five dollars. That was a lot of money in those times.”11

Another of Kaukl's responsibilities involved maintaining the game farm's live animal exhibits, and his affinity for furbearers won him some notoriety.

In November 1954 Wisconsin State Journal staff writer John Newhouse wrote of Kaukl's ability to tame two badgers:

If there ever was a fighting animal, it's the squat, powerful badger.

And it's extremely rare when one is tamed, for badgers don't cotton much to mankind.

That's why the seasoned animal men at the state game farm here are impressed with the job that Marvin (Koke) Kaukl is doing at the farm with a pair of badgers approaching maturity.12

Through the years the fur programs at the game farm were discontinued, with little remaining by the early 1960s. With the modern-day decline of the fur farm industry and the explosion in raccoon numbers in the wild, the old fur programs of the state game farm speak of a different era. All that remains today of the once-vital fur section are concrete foundations of buildings long ago torn down, overgrown with woods and brush, and Marv Kaukl's memories.