Chapter 24

Pioneer Bits and Pieces

While researching articles for this book, I frequently came across interesting tidbits of Wisconsin sporting history that don't warrant a full story but are interesting little slices of a long past Wisconsin. In the early 1900s newspapers across the state frequently ran stories about the earliest of Wisconsin pioneers and their hunting and fishing memories.

Fishing with Jackson

While many of us are familiar with the Wisconsin fishing experiences of U.S. presidents such as Dwight Eisenhower and Calvin Coolidge, I ran across another interesting connection between Wisconsin and presidential fishing pursuits.

In 1906, the Appleton Crescent ran a story about a local woman who, besides having the distinction of being the first woman in Appleton to ride in the first covered carriage (an import from Massachusetts), was also lucky enough to have been a fishing companion of the seventh president of the United States, Andrew Jackson—hero of the Battle of New Orleans in the War of 1812.

As a child, Elizabeth Mereness (née Kling) lived on a farm located very near Sharron Springs, a health resort in New York frequented by southerners, including Jackson, who were escaping oppressive southern summer temperatures. Mereness first met Jackson in the summer of 1833. The former president took a liking to Elizabeth and her sister Eveline and frequently fished with the two girls on a five-acre pond at the Kling farm. The girls dug worms for Jackson, and he always gave the fish he caught to them.1

An early Appleton-area settler, Mereness was seventy-seven years old when interviewed by the Crescent reporter. She recalled that Jackson “looked as much like the typical picture of ‘Uncle Sam’ as you could imagine. His hat was shaped just like Uncle Sam's. It was an old grey hat, dirty and greasy in the front. His face was the same long, thin one which appears in histories.”2

Jackson continued to spend summers at Sharron Springs and frequent the Kling farm. He died in 1845 at the age of seventy-eight.

Early Madison Hunting

In 1923 the Madison Capital Times carried the hunting and fishing reminiscences of an early settler known only as the “Early Madisonian”:

In 1845 Madison was a small hamlet standing in a forest thicket. There were no streets or walks. Prairies and groves, as yet unmarked by evidences of man's presence in the surrounding country, reached to the edges of the lakes. But game was plentiful and fishing most successfully carried on.

Prairie chickens were shot on the capitol square, and quail also filled the game bag. Rabbits were plentiful. An hour's fishing would often give a boatload of finny beauties to be divided among neighbors by the angler.

Deer were numerous, and from the cabin doorway or window, could often be shot. The last one killed on the town site was an old buck, who had become so wise he eluded his fate for several years.

Bear were common at this period, and wolves innumerable. The latter became so troublesome that an official wolf-catcher was engaged.

Prairie fires annually crossed the site from one marsh to another, passing through the timber between Capitol Park and Fourth Lake. Unquestionably a good deal of what may be called smaller game perished in the flames. But wild duck and geese escaped—either by high flight or by early migration southward, and each returning spring brought the blackbirds and pigeons as excellent foundations for pot pie.3

Oldest Hunter in Superior

G. J. Anderson of Solon Springs, touted as Douglas County's oldest deer hunter by the Superior Telegram in November 1914, provided his early hunting memories to a Telegram reporter.

Anderson told the reporter “how he had shot the first deer killed by him in Douglas County in November 1880, on the site where the Hotel Superior now stands.”4

“I never thought then that I was standing on what would be in a comparatively short time the busiest corner in a large city,” reminisced Anderson. “All around me were huge pine trees, and I remember thinking what fine logs they would make.”5

Anderson was an old man when he was interviewed, but he confidently told the reporter, “I'm going to get my venison this year again.”6

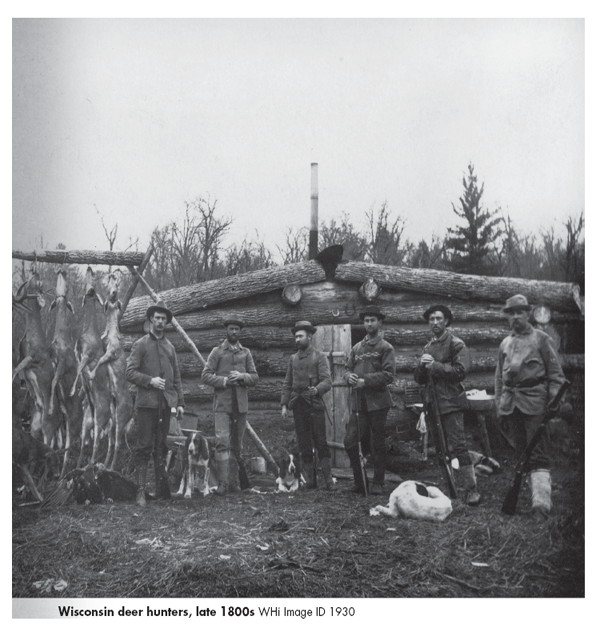

Deer Stacked Like Cordwood

In 1927 the Superior Telegram interviewed another area old-timer, Pat Simons. He recalled the market hunting days of the mid-1800s.

“I've seen deer stacked like cordwood as far as from here to that shed, and 20 feet high,” Simons told the newspaper. “Fellows made their living that way. They'd go into the woods in the winter and shoot deer and haul them out with teams later. They were shipped to the markets. The deer were thick. One could shoot them from the door of the cabin. Often they would come right into town.”7

Simons also remembered how the now extinct passenger pigeon existed in huge numbers in the area.

“Partridges were thick around here, and wild pigeons. I've seen the pigeons come down and cover whole trees,” he remarked.8

Hunting for the Logging Camps

Also in 1927 the Eau Claire Telegram interviewed one of the last of the white pine loggers, the fast-disappearing generation of men who had cleared the northern pineries. James D. Terry of Augusta felled trees and drove logs in the Eau Claire and Chippewa Falls area in the 1860s and ‘70s. He told the reporter that it became his job to supply the lumber camps with venison:

I was to receive four dollars per head for the deer killed, also my board. I had only to show the toters where the deer could be found. I began hunting November first and by January had killed thirty-eight deer and two bear, an old one and a cub. I was paid ten dollars for the large bear and five dollars for the cub.

After January first I began working as a chopper, and in the spring helped drive the logs down to the Five Mile Dam, at what is now Altoona.9

Terry spent two winters hunting for the lumber camps.

“Both winters I hunted alone,” he remembered. “The gun I used was a double barrel, muzzleloader rifle, about thirty-eight caliber, and was made by Mr. Schlegelmilch senior, the pioneer gunsmith of Eau Claire.”10

Those early pioneers are all long gone now, but luckily some of their stories were recorded by the newspapers. Wisconsin still has its share of old-time hunters, trappers, and anglers who can fondly recall the Wisconsin outdoors as they existed in the 1930s, ‘40s, and ‘50s. It is hoped that their stories will find their way to the archives of history as well.