Trauma in Pregnancy

Perspective

Trauma occurs in 6 to 7% of all pregnancies. It is the leading nonobstetric cause of maternal death, accounting for close to 50% of fatalities in pregnant women.1 The most common causes of injury in pregnancy, in order of frequency, that result in emergency department (ED) visits are motor vehicle collisions (MVCs), interpersonal violence, and falls.2–5 Patients with penetrating injuries are seen more frequently in EDs in inner city medical centers.6 Of note, 8% of women aged 15 to 40 admitted to a trauma center do not yet know they are pregnant.7 Commonly used thresholds of fetal viability are an estimated gestational age of 24 to 26 weeks or an estimated fetal weight of 500 g. Only viable fetuses are monitored, because no obstetric intervention will alter the outcome with a previable fetus.8 Counseling on proper seatbelt and alcohol use and screening for interpersonal violence may help to reduce the morbidity and mortality rates for pregnant patients. Although the essential principles of trauma management remain unchanged in the pregnant patient, a number of special points need to be considered. Pregnancy causes alterations in physiology and anatomy that affect multiple organ systems. Although there are two lives involved, maternal life takes priority.

Principles of Disease—Changes of Pregnancy

Cardiovascular

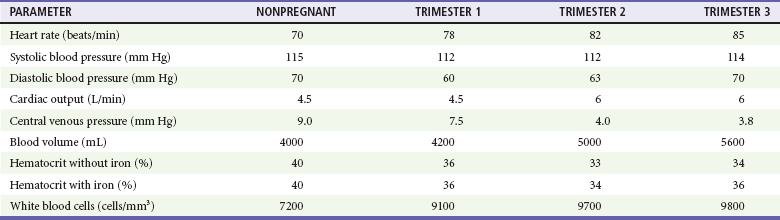

The normal cardiovascular changes of pregnancy can alter the presentation of shock and vascular events (Table 37-1).

Table 37-1

Hemodynamic Changes of Pregnancy (Mean Values)

Data from de Swiet M: The cardiovascular system. In Hytten F, Chamberlain G, eds: Clinical Physiology in Obstetrics. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1980, pp 3-42; Colditz RB, Josey WE: Central venous pressure in supine position during normal pregnancy. Comparative determinations during first, second and third trimesters. Obstet Gynecol 36:769, 1970; Letsky E: The haematological system. In Hytten RF, Chamberlin G, eds: Clinical Physiology in Obstetrics. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Scientific Publications, 1980, pp 43-78; and Cruikshank DP: Anatomic and physiologic alterations of pregnancy that modify the response to trauma. In Buchsbaum HJ, ed: Trauma in Pregnancy. Philadelphia: WB Saunders, 1979, pp 21-39.

Some Alterations Mimic Shock.: Blood pressure declines in the first trimester, levels out in the second trimester, and then returns to nonpregnant levels during the third trimester. The decline in systole is small, 2 to 4 mm Hg, whereas diastole falls 5 to 15 mm Hg. Heart rate increases in pregnancy but does not rise by more than 10 to 15 beats per minute above baseline (mean of approximately 90 beats/min).

A major contributor to maternal hypotension is the supine hypotensive syndrome. After 20 weeks' gestation, the uterus has risen to the level of the inferior vena cava, resulting in compression when the mother is supine. Such caval obstruction diminishes cardiac preload, which can decrease cardiac output by as much as 28%, resulting in reduced systolic blood pressure by 30 mm Hg. In late pregnancy, it is common for the inferior vena cava to become completely occluded when the pregnant patient is supine. Attempts at resuscitation will be improved if compression is relieved. In determining whether observed hypotension is related to positioning, the pregnant woman's pelvis can be tilted so that the uterus is displaced from the inferior vena cava, (i.e, tilt the patient onto her left side unless otherwise prevented because of other injuries). The uterus can also be manually pushed to the left by with two hands, pushing the uterus toward the patient's head. One early study found that tilting limited to only about 15 degrees may only partially resolve vena caval obstruction9; thus, maintaining a position between 15 and 30 degrees is optimal. Elevating the patient's legs, where blood may pool owing to increased capacitance, will improve venous return.

Similarly, central venous pressure (CVP) measurements can be lowered in the last two trimesters by inferior vena caval compression. Normal CVP during pregnancy is approximately 12 mm Hg.

Alterations That May Mask Hypovolemic Shock.: Blood volume gradually increases during pregnancy, starting at 6 to 8 weeks' gestation, to as much as 45% above normal, peaking at 32 to 34 weeks' gestation. Blood volumes become increasingly larger for multigravidas, twins, triplets, and quadruplets. With this increased circulatory reserve, clinical signs of maternal hypotension from acute traumatic bleeding may be delayed.

Some Alterations Can Exacerbate Traumatic Bleeding.: By the beginning of the second trimester and throughout the remaining pregnancy, cardiac output is increased 40%, to 6 L/min. Blood flow to the uterus increases from 60 mL/min before pregnancy to 600 mL/min at term. This hyperdynamic state is needed to maintain adequate oxygen delivery to the fetus. Because the mother's total circulating blood volume flows through the uterus every 8 to 11 minutes at term, this organ can be a major source of blood loss when injured. By the third trimester, there is also marked venous congestion in the pelvis and lower extremities, increasing the potential for hemorrhage from both bony and soft tissue pelvic injuries.

Compression of the lower abdominal venous system by the gravid uterus increases peripheral venous pressure and volume in the legs, creating the potential for brisk blood loss from leg wounds. This alteration can play an important role in procedures that may be necessary for maternal resuscitation, such as central venous catheter placement.

Pulmonary

The pregnant woman at term has a significantly reduced oxygen reserve. This effect comes from a reduction in functional residual capacity caused by diaphragm elevation and an increase in oxygen consumption related to the growing fetus, uterus, and placenta. In a classic study, Archer and Marx observed that mean arterial oxygen tension dropped by 29% in pregnant women at term during 60 seconds of apnea but just 11% in nonpregnant women. Labor accelerates this decline by a further 7%.10 In addition, minute ventilation increases, leading to hypocapnea. Therefore an arterial partial pressure of carbon dioxide (PaCO2) of 35 to 40 mm Hg may indicate inadequate ventilation and impending respiratory decompensation in the pregnant patient. At signs of respiratory compromise or hypoxia, endotracheal intubation should be considered, as maternal hypoxia rapidly leads to fetal hypoxia, distress, and possibly demise. There are no contraindications to rapid sequence intubation during pregnancy. Bag-valve-mask ventilation is more difficult in the pregnant patient.

Gastrointestinal

Gastroesophageal sphincter response is reduced in pregnancy and gastrointestinal motility is decreased, both of which increase the possibility of aspiration during reduced levels of consciousness and intubation. The stomach's increased acid production in pregnancy makes aspiration more ominous than usual. Therefore early gastric decompression should be considered in appropriate circumstances.

Anatomic Changes in Pregnancy

The uterus remains an intrapelvic organ until approximately the 12th week of gestation. It reaches the umbilicus by 20 weeks and the costal margins by 34 to 36 weeks. It grows from a 7-cm, 70-g organ to a 36-cm, 1000-g structure at term. As a result of this growing mass, the normal anatomic location and function of multiple structures are altered.

The diaphragm progressively rises in pregnancy, with compensatory flaring of the ribs. Pneumothorax may be exacerbated and tension pneumothorax can develop more quickly in pregnancy because of this diaphragm elevation, combined with pulmonary hyperventilation. For thoracostomies done in the third trimester, the chest tube should be placed one or two interspaces higher than the usual fifth interspace site to allow for diaphragm elevation.

Abdominal viscera are pushed upward by the enlarging uterus, resulting in altered pain location patterns. The gravid uterus itself tends to protect abdominal organs from trauma but substantially increases the likelihood of bowel injury with penetrating trauma to the upper abdomen. Conversely, the upward displacement of the bowel makes it less susceptible to blunt trauma. The stretching of the abdominal wall modifies the normal response to peritoneal irritation. Therefore expected muscle guarding and rebound can be progressively blunted as pregnancy approaches term, despite significant intra-abdominal bleeding and organ injury, another factor that may lead to underestimation of the extent and gravity of maternal trauma.

In the first trimester, the bony pelvis shields the uterus. After the third month, the uterus rises out of the pelvis and becomes vulnerable to direct injury. The bladder is also displaced into the abdominal cavity beyond 12 weeks' gestation, thereby becoming more vulnerable to injury. Like the uterus, the bladder becomes hyperemic, and injury may lead to a marked increase in blood loss compared with similar injury in a nonpregnant patient.

Imaging studies may show ureteral dilation that can be physiologic secondary to smooth muscle relaxation or caused by compression from the gravid uterus. Thus hydronephrosis is not necessarily pathologic. The ligaments of the symphysis pubis and sacroiliac joints are loosened during pregnancy. As a result, a baseline diastasis of the pubic symphysis may exist that can be mistaken for pelvic disruption on a radiograph.

Changes in Laboratory Values with Pregnancy

The physiologic anemia of pregnancy, resulting from a 48 to 58% increase in plasma volume and only an 18% increase in red blood cells, causes hematocrits of 32 to 34% by the 32nd to 34th week. Despite the lower hematocrit, there is actually an overall increase in oxygen-carrying capacity because of an increased total red blood cell mass.

Placental progesterone directly stimulates the medullary respiratory center, producing a PaCO2 of 30 mm Hg from the second trimester until term. The subsequent compensatory lowering of serum bicarbonate slightly reduces blood-buffering capacity for stress situations. A PaCO2 of 40 mm Hg in the latter half of pregnancy reflects inadequate ventilation and potential respiratory acidosis that could precipitate fetal distress.

Electrocardiographic changes include a left-axis shift averaging 15 degrees, caused by diaphragm elevation. Consequently, flattened T waves or Q waves in leads III and augmented voltage unipolar left limb lead may be seen.

Clinical Features of Trauma in Pregnancy

The findings of the physical examination in the pregnant woman with blunt trauma are not reliable in predicting adverse obstetric outcomes. However, risk factors that are significantly predictive of contractions or preterm labor include gestational age greater than 35 weeks, assaults, and pedestrian collisions. In gravid patients, penetrating trauma of the abdomen has an increased likelihood of causing injuries of the bowel, liver, or spleen.

Fetal mortality rates range from 4 to 40% after maternal trauma, with most likely causes of fetal death occurring from placental abruption, maternal shock, and maternal death, in order of decreasing incidence.11 Risk factors significantly predictive of fetal death include ejections, motorcycle and pedestrian collisions, maternal death, maternal tachycardia, abnormal fetal heart rate, lack of restraints, and an Injury Severity Score greater than 9.8

Unbelted or improperly restrained pregnant women are twice as likely to experience excessive maternal bleeding, and fetal death is three times more likely to occur.11–13 For low- to moderate-severity crashes (constituting 95% of all MVCs), proper restraint use, with or without air bag deployment, generally leads to acceptable fetal outcomes. For high-severity crashes, even proper restraint does not improve fetal outcome.14

Pregnant crash-test-dummy trials show that improper placement of the lap belt over the pregnant abdomen causes a threefold to fourfold increase in force transmission through the uterus. The lowest force transmission readings through the uterus occur when a three-point seat belt is used properly. For correct position, the lap belt should be placed under the gravid abdomen, snugly over the thighs, with the shoulder harness off to the side of the uterus, between the breasts and over the midline of the clavicle.15 Women who receive information on seat belt use during pregnancy from a health care worker are statistically more likely to use seat belts and to use them properly than uninformed controls.15

Interpersonal Violence

Although it has been previously documented that intimate partner violence against women affects one in four U.S. women, and numerous health consequences have been associated with being a victim of such violence, a 2006 study by Silverman and colleagues conclusively demonstrated that physical abuse from husbands or boyfriends compromises a woman's health during pregnancy, as well as her likelihood of carrying a child to term and the health of her newborn.16 Women experiencing abuse in the year before or during a pregnancy were 40 to 60% more likely than nonabused women to report high blood pressure, vaginal bleeding, severe nausea, kidney or urinary tract infections, and hospitalization during that pregnancy. Abused pregnant women were 37% more likely to deliver preterm, and children of abused pregnant women were 17% more likely to be born underweight. These conditions pose grave health risks to newborns, and children born to abused mothers were over 30% more likely than other children to require intensive care at birth.16–18 Physicians detect only a minority of cases, which supports the need for routine screening for interpersonal violence in pregnant patients.

Falls

Falls become more prevalent after the 20th week of pregnancy.2 Protuberance of the abdomen, loosening of pelvic ligaments, strain on the lower back, and fatigability contribute to this problem. In a given pregnancy, about 2% of pregnant women sustain repeated direct blows to the abdomen because of falling more than once. Although repeated falls often trigger premature contractions, they seldom result in immediate labor and delivery.

Penetrating Trauma

The gravid uterus alters injury patterns to the mother. There is an increased probability of harm (approaching 100%) to the bowel, liver, or spleen if the entrance of the penetrating object is in the upper abdomen. When the entry site is anterior and below the uterine fundus, visceral injuries are less likely. Although the enlarging uterus can act as a shield against intra-abdominal injuries in the mother, it makes the fetus more susceptible to injury. A high fetal death rate from penetrating trauma to the uterus has been reported, but a lower fetal death rate for maternal injuries above the uterus.19

Fetal Injury

Pregnancy does not alter rates of maternal mortality caused by trauma. However, trauma is associated with a high risk of fetal loss. When the mother sustains a severe level of injury, poor fetal outcome is predicted by maternal hypotension and acidosis (hypoxia, lowered pH, lowered bicarbonate) and a fetal heart rate of less than 110 beats/min.5,6,20 When the mother sustains life-threatening injuries, there is a 40% chance of fetal demise, compared with a less than 2% chance in cases of non–life-threatening maternal injuries. Maternal age and gestational age may also be important factors in determining fetal outcome.21

Maternal disseminated intravascular coagulation (DIC), which may be caused by placental products entering the maternal circulation, is a significant predictor of fetal mortality.11 For women with less severe trauma, fetal outcome is not predicted by maternal vital signs, abdominal tenderness, blood tests, or ultrasonography (US) results. Only cardiotocographic monitoring for a minimum of 4 hours is useful in predicting fetal outcome.3

Fatal in utero fetal injuries from blunt trauma usually involve intracranial hemorrhage and skull fractures. Such head injury is often secondary to fractured maternal pelvic bones striking the fetal skull as a result of vertex lie. Pelvic and acetabular fractures during pregnancy are associated with a high maternal (9%) and a higher fetal (38%) mortality rate.22 With penetrating trauma, gunshot wounds to the uterus are associated with a high incidence of fetal injury and fetal mortality. Stab wounds to the uterus produce substantial morbidity and mortality to the fetus.11

Placental Injury

In blunt trauma, 50 to 70% of all fetal losses result from placental abruption.19,23 It is the leading cause of fetal death after blunt trauma.

Placental separation results when the inelastic placenta shears away from the elastic uterus during sudden deformation of the uterus. Because deceleration forces can be as damaging to the placenta as direct uterine trauma, abruption can occur with little or no external sign of injury to the abdominal wall. Because all gas exchange between the mother and fetus occurs across the placenta, abruption inhibits the flow of oxygen to the fetus and causes in utero carbon dioxide (CO2) accumulation. Such hypoxia and acidosis can lead to fetal distress. Sustained uterine contractions induced by intrauterine hemorrhage also inhibit uterine blood flow, further contributing to fetal hypoxia.24

The diagnosis of abruption is a clinical one, and US and the Kleihauer-Betke test are of limited value.24 Classic clinical findings of abruption may include vaginal bleeding, abdominal cramps, uterine tenderness, maternal hypovolemia (up to 2 L of blood can accumulate in the gravid uterus), or a change in the fetal heart rate. However, many cases of placental abruption after trauma show no evidence of vaginal bleeding.11

The most sensitive indicator of placental abruption is fetal distress. Therefore prompt fetal monitoring is a very important assessment technique in trauma during pregnancy. There is also a close linkage of abruption to uterine activity, with increased frequency of contractions associated with abruption. US is less than 50% accurate as a first-line test in detecting placental abruption.19,25 If the abruption bleeds externally, not enough blood collects to be seen sonographically. Even with significant intrauterine blood accumulation, accurate US diagnosis may be difficult because of placental position (i.e., posterior) and confounding uterine or placental structural conditions.

Placental abruption is associated with an overall 8.9-fold increased risk of stillbirth (>20 weeks) and a 3.9-fold increased risk of preterm delivery (before 37 weeks). The extent of placental separation affects stillbirth rates. At 50% separation, there is a fourfold increased risk of stillbirth, and a more profound 31.5-fold increased risk of stillbirth is present at 75% separation. The risk of preterm delivery is substantially increased with even mild abruptions; a 25% separation carries a 5.5-fold increased risk of preterm delivery.24,25

When mother and fetus are stable, expectant management can be tried for partial placental abruptions of less than 25%. This usually applies to fetuses of less than 32 weeks' gestation in which the likelihood of morbidity and mortality associated with prematurity makes delivery management risky. Expectant care in stable patients may allow further fetal maturation and improved outcome. If expectant management is pursued, close maternal and fetal monitoring is needed to ensure the well-being of both patients. The ability to perform an immediate cesarean section is necessary because there may be little time between the appearance of fetal distress from further placental separation and the occurrence of fetal death. After 32 weeks' gestation the risk of further placental separation outweighs the benefits of further fetal maturation, so intervention may be indicated.11,25

Women with placental abruption are more likely to have coagulopathies than those without abruption. The injured placenta can release thromboplastin into the maternal circulation, resulting in DIC, whereas the damaged uterus can disperse plasminogen activator and trigger fibrinolysis. The precipitation of DIC is directly related to the degree of placental separation. Severe clotting disorders rarely occur unless separation of the placenta is significant enough to result in fetal demise.24,25

Uterine Injury

The most common obstetric problem caused by maternal trauma is uterine contractions.3,4 Myometrial and decidual cells, irritated by contusion or placental separation, release prostaglandins that stimulate uterine contractions. Progression to labor depends on the extent of uterine damage, the amount of prostaglandins released, and the gestational age of the pregnancy. The routine use of tocolytics for premature labor has come under question because most contractions stop spontaneously. Contractions that are not self-limited are often induced by some pathologic condition, such as underlying placental abruption, which is a contraindication to tocolytic therapy. Older studies describe this risk as relative and have used tocolysis successfully with careful evaluation and intensive monitoring to continue the pregnancy and enhance fetal maturity.26 The option to use tocolytics ends when cervical dilation reaches 4 cm.

Uterine rupture is a rare event. It is most often caused by severe vehicular crashes in which pelvic fractures strike directly against the uterus. Uterine rupture may occur from stab wounds and gunshot injuries, but this appears to be rare.11,19 Maternal shock, abdominal pain, easily palpable fetal anatomy caused by extrusion into the abdomen, and fetal demise are typical findings on examination. Diagnosing uterine rupture can be difficult. A fractured liver or spleen can produce similar signs and symptoms of peritoneal irritation, hemoperitoneum, and unstable vital signs. Optimal treatment, between suturing the tear or performing a hysterectomy, depends on the extent of uterus and uterine vessel tears and the importance of future childbearing.

Diagnostic Strategies

Plain Radiographs

Adverse effects to the fetus are unlikely if radiation exposure is less than 5 to 10 radiation-absorbed doses (rad). Less than 1% of trauma patients are exposed to more than 3 rad. Sensitivity to radiation is greater during intrauterine development than at any other time of life, especially in the first trimester (i.e., when the embryo undergoes organogenesis in weeks 2-9). However, the risk to the fetus of a 1-rad (1000 mrad) exposure, approximately 0.003%, is thousands of times smaller than the spontaneous risks of malformations, abortions, or genetic disease. Intrauterine exposure to 10 rad does not appear to cause a significant increase in congenital malformations, intrauterine growth retardation, or miscarriage but is associated with a small increase in the number of childhood cancers.27 Pathologic conditions more readily appear with intrauterine radiation doses of 15 rad or greater.

Providing information on radiation exposure from diagnostic radiographs is difficult. The individual amount of fetal dosage may vary by a factor of 50 or more, depending on the equipment used, technique, number of radiographs done in a complete study, maternal size, and fetal-uterine size. Diagnostic radiographic studies should be performed with regard for fetal protection, but necessary diagnostic studies of the traumatized pregnant patient should not be withheld out of concern for fetal radiation exposure.11,19 When appropriate, fetal irradiation should be minimized by limiting the scope of the examination and using technical means such as shielding and collimation. Table 37-2 provides estimated radiation doses from various types of examinations.

Table 37-2

Estimated Radiation Dose to the Unshielded Ovaries and Pelvic Uterus

| IMAGING STUDY | UTERINE RADIATION DOSE (MRAD)* |

| Plain-Film Radiography | |

| Cervical spine | Undetectable |

| Thoracic spine | <1 |

| Chest (PA) | <1 |

| Chest (AP) | <5 |

| Extremities (femur) | <50 |

| Hip | 10-210 |

| Lumbar spine | 31-400 |

| Pelvis | 140-2200 |

| KUB | 200-503 |

| Intravenous pyelogram | 503-880 |

| Urethrocystogram | 1500 |

| Computed Tomography | |

| Head | <50 |

| Thorax | 10-590 |

| Abdomen | 2800-4600 |

| Pelvis | 1940-5000 |

| Angiography | |

| Cerebral | <100 |

| Cardiac catheterization | <500 |

| Aortography | <100 |

AP, anteroposterior; KUB, kidney, ureter, and bladder; PA, posteroanterior.

*mrad, millirad; dose increases as the fetus grows to occupy more of the abdomen.

Data from Berlin L: Radiation exposure and the pregnant patient. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1996; 167:1377; North DL: Radiation doses in pregnant women. J Am Coll Surg 2002; 194:100; Damilakis J, Perisinakis K, Voloudaki A, Gourtsoyiannis N: Estimation of fetal radiation dose from computed tomography scanning in late pregnancy: Depth-dose data from routine examinations. Invest Radiol 35:527, 2000. [published correction appears in Invest Radiol 35:706, 2000].

Ultrasonography

US is the best modality for simultaneous assessment of both the mother and the fetus. It has a sensitivity of 88%, a specificity of 99%, and an accuracy of 97% for detecting intra-abdominal injuries in blunt trauma in all patients. In the pregnant patient, it is most useful in detecting major abdominal injury (sensitivity 80%, specificity 100%) and establishing fetal well-being or demise, gestational age, and placental location.28,29

Sonography is a safe and effective screening examination that can obviate more hazardous tests such as computed tomography (CT), cystography, and diagnostic peritoneal lavage (DPL) in most pregnant patients with trauma who require an objective evaluation of the abdomen. Limitations in accuracy include operator experience, patient obesity, the presence of subcutaneous air, and a history of multiple abdominal operations. If ultrasound findings are equivocal and the patient is hemodynamically unstable, DPL performed in an open and suprauterine fashion is indicated. Diagnostic peritoneal aspiration (DPA) may be considered in conjunction with a trauma surgeon; however, this procedure also poses risks.

Computed Tomography and Magnetic Resonance Imaging Scans

CT and, increasingly, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) studies are used in evaluating abdominal trauma in pregnancy. If US is indeterminate and the patient's condition is stable, CT and MRI have the potential to identify specific organ damage. They are particularly useful in assessing penetrating wounds of the flank and back. CT can miss diaphragm and bowel injuries. Both of these studies generally lack portability, and trauma patients may have to be taken from the closely monitored environment of the ED to a distant radiography suite.

Radiation from CT is a concern in the pregnant trauma patient. However, with shielding, fetal exposure from head and chest CT scans can be kept below an acceptable 1-rad limit. CT of the abdomen above the uterus can be done with less than 3 rad of exposure to the fetus.30 Pelvic CT, centered over the fetus, produces a more prohibitive 3- to 9-rad dose; spiral CT can further reduce radiation dosage.30 Radiation exposure ultimately depends on the patient, scanner, and technique used in performing the study (see Table 37-2). MRI scanners use no radiation and have not been associated with significant fetal disease or disability.

Special Procedures

In unstable trauma patients with equivocal or negative findings on US, DPL can be done in any trimester by an open technique above the uterus. The gravid uterus, in the later trimesters, makes the procedure more risky and technically challenging. In blunt trauma the gravid uterus does not compartmentalize intraperitoneal hemorrhage and does not reduce the accuracy of DPL for selecting patients who need operative intervention for intra-abdominal bleeding. DPL is limited in detecting bowel perforations and does not assess retroperitoneal and intrauterine pathology.

Management

As with any trauma, advance notification and preparation can be helpful. Depending on mechanism, maternal condition, and gestational age, the emergency physician should consider early notification or consultation with an obstetrician, neonatologist, or pediatrician (or all three). A fetal monitor, portable US, and neonatal resuscitation equipment should be immediately available.

Maternal Resuscitation

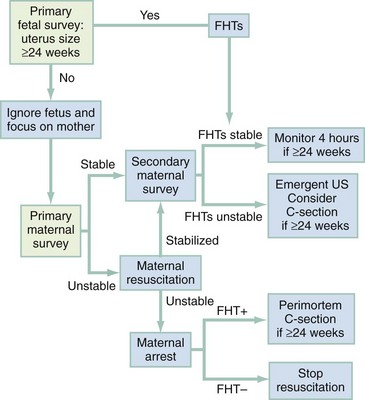

The primary survey focuses on the mother. However, because two patients are present, it is reasonable also to gather preliminary information about the fetus in the primary survey (Fig. 37-1).

Figure 37-1 Decision-making algorithm in emergency obstetric care. C-section, cesarean section; FHTs, fetal heart tones; US, ultrasonography.

Airway and Breathing.: Oxygen therapy should be instituted early. Because of reduced oxygen reserve and increased oxygen consumption, the traumatized pregnant woman can quickly become hypoxic. The fetus is very vulnerable to any reduction in oxygen delivery. Supplemental oxygen should be continued throughout maternal resuscitation and evaluation.

A secure airway is critical to an optimum outcome. Not only does it enable proper oxygenation, but it negates the higher risk of aspiration in pregnancy. Rapid sequence intubation is recommended when intubation is performed. Mechanical respirators need to be adjusted for increased tidal volumes and respiratory alkalosis consistent with the physiologic PaCO2 of 30 mm Hg in the last stage of pregnancy.

Circulation.: Any time significant maternal injury is suggested by the mechanism of injury or clinical findings, early intravenous access for volume resuscitation is indicated. Maternal blood pressure and heart rate are not consistently reliable predictors of fetal and maternal well-being.11,19 Because of an expanded circulating volume, the mother can be bleeding but not show early signs of hypotension. The uterus is not a critical organ, and its blood flow is markedly reduced when the maternal circulation is compromised. As a result, after an acute blood loss, uterine blood flow can be substantially decreased while maternal blood pressure remains normal. Consequently, the pregnant woman with borderline hemodynamic stability probably already has a jeopardized fetus. When traditional signs of shock appear, fetal compromise can be far advanced. Vasopressors should be avoided because they produce fetal distress by further decreasing uterine blood flow.

Beyond 20 weeks' gestation, tilting the patient to approximately 30 degrees to the left on a backboard or elevating the right hip reduces the compression on the inferior vena cava caused by the gravid uterus. Tilting to the right is less effective in removing the uterus from the inferior vena cava; manually displacing the uterus upward and leftward is more effective.

For severe injuries, a CVP line is helpful in assessing cardiac preload. CVP pressures decline as pregnancy progresses because of inferior vena caval compression by the gravid uterus. Therefore correction to nonpregnant normal pressures may be unnecessary. Instead, it is more valuable to focus on trends of how the CVP responds to fluid challenges. A Foley catheter for measuring urine output provides further information on circulatory volume status.

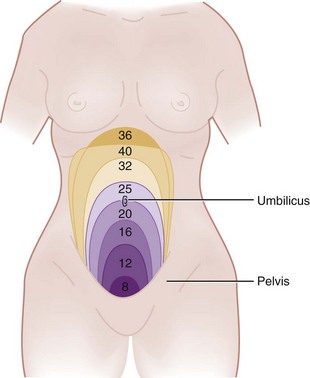

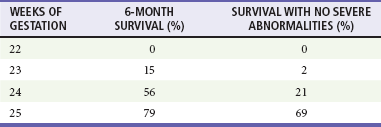

With trauma in pregnancy, the primary survey can be modified to assess uterine size and the presence of fetal heart tones. Uterine size, measured from the symphysis pubis to the fundus, is the quickest means of estimating gestational age. This distance in centimeters equals the gestational age in weeks (e.g., 24 cm = 24 weeks), which allows some early indication of fetal viability if delivery is necessary (Fig. 37-2). Usually, 24 to 26 weeks is used as the cutoff point for fetal viability (Table 37-3). As a rough guide, the fetus is potentially viable when the dome of the uterus extends beyond the umbilicus. Fetal heart tones can be detected by auscultation at 20 weeks' gestation or by Doppler probe at 10 to 14 weeks. If either the uterus is less than 24 cm in size or fetal heart tones are absent, the pregnancy is probably too early to be viable, and treatment is directed solely at the mother.

Table 37-3

Data from Morris JA Jr, et al: Infant survival after cesarean section for trauma. Ann Surg 223:481, 1996.

Secondary Survey

The secondary survey involves a detailed examination of the patient but is also modified to gather additional information about the maternal abdomen and the fetus. Physical examination of the abdomen, frequently unreliable in the nonpregnant patient, is more inaccurate with changing organ position, abdominal wall stretching in advancing pregnancy, and uterine contraction pains. Still, information can be gathered about uterine tenderness, contraction frequency, and vaginal bleeding.

Pelvic examination begins with sterile speculum examination to allow direct visualization to enable detection of possible trauma in the genital tract, the degree of cervical dilation, and the source of any observed vaginal fluid. Vaginal bleeding suggests placental abruption, and a watery discharge suggests rupture of the membranes. If a vaginal fluid sample placed on a slide dries and crystallizes in a ferning pattern, it is amniotic fluid and not urine. Cervical cultures for group B streptococci, Neisseria gonorrhoeae, and Chlamydia should be performed if there is evidence of amniotic fluid leak. Bimanual examination should be limited to assessing for pelvic bone injury or progression of advanced labor. If the mechanism of injury is significant enough and the fetus is judged to be viable, early involvement of an obstetrician may enhance the fetal outcome.

Fetal Evaluation

Fetal evaluation in the secondary survey focuses on the fetal heart rate and detection of fetal movement. When the presence of fetal heart tones has been confirmed, intermittent monitoring of fetal heart rate is sufficient for the previable fetus. If the fetus is viable (i.e., 24 weeks or more), continuous external monitoring initiated quickly and maintained throughout all diagnostic and therapeutic procedures may be useful in directing management. Such monitoring can also benefit the mother because fetal hemodynamics are more sensitive to decreases in maternal blood flow and oxygenation than are most measures of the mother. Fetal distress can be a sign of occult maternal distress. However, fetal distress and even demise can occur with seemingly minor maternal trauma. Signs of fetal distress include an abnormal baseline heart rate, decreased variability of heart rate, and fetal decelerations after contractions.11

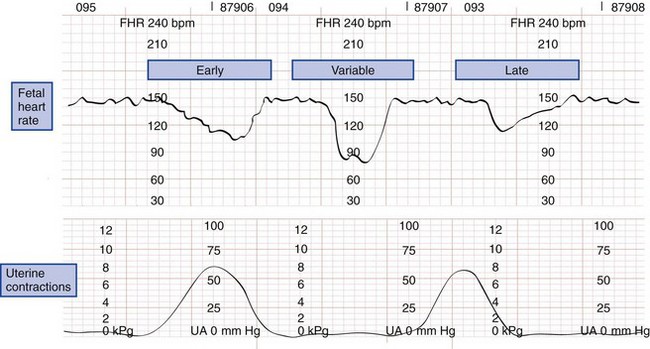

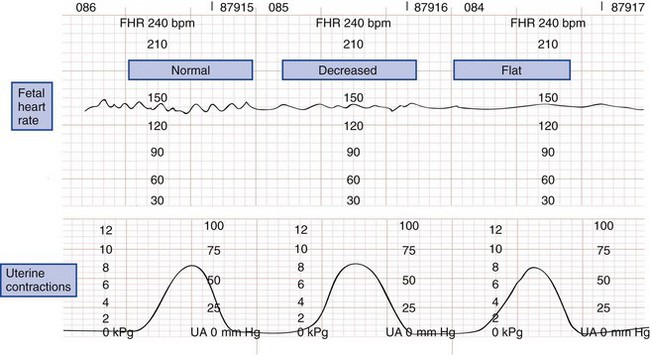

The normal fetal heart rate ranges from 120 to 160 beats/min; rates outside or trending toward these limits are ominous. Heart rate variability has two components. Beat-to-beat variability measures autonomic nervous function, whereas long-term variability indicates fetal activity. Heart rate variability increases with gestational age. The loss of beat-to-beat and long-term variability warns of fetal central nervous system depression and reduced fetal movement caused by fetal distress (Fig. 37-3).11,19

Figure 37-3 Types of fetal heart rate variability. bpm, beats per minute; FHR, fetal heart rate; UA, uterine activity.

Late decelerations are an indication of fetal hypoxia. These decelerations are relatively small in amplitude and occur after the peak or conclusion of a uterine contraction. By comparison, early decelerations are larger, occur with the contraction, and recover to baseline immediately after the contraction. Early decelerations may be vagally mediated when uterine contractions squeeze the fetal head, stretch the neck, or compress the umbilical cord. Variable decelerations are large, occur at any time, and are possibly caused by umbilical cord compression (Fig. 37-4).

Laboratory

Besides routine trauma blood work, emergency laboratory tests for a traumatized pregnant patient include a blood type with Rh status. In apparently stable pregnant patients, a low serum bicarbonate level may indicate occult maternal shock. Interpretation of bicarbonate results requires consideration of the physiologic changes of the bicarbonate level that occur in the later stages of pregnancy as a result of respiratory alkalosis. Arterial blood gases can allow detection of maternal hypoxia and acidosis, whereas pulse oximetry can be used to monitor oxygen saturation. Coagulation studies are important in directing management of patients with multisystem trauma or when the diagnosis of placental abruption is considered. The main difference in the laboratory workup between the nonpregnant and the pregnant trauma patient is the need to determine Rh status and quantitative β-human chorionic gonadotropin (β-hCG) in the pregnant patient; besides this, the physician should order any and all laboratory tests that would be ordered for any trauma patient.

Kleihauer-Betke Test and Fetomaternal Hemorrhage

Fetomaternal hemorrhage (FMH), the transplacental bleeding of fetal blood into the normally separate maternal circulation, is a unique complication of pregnancy. The reported incidence of FMH after trauma is 8 to 30% (with a range of 2.5-115 mL of blood) compared with 2 to 8% (range of 0.1-8 mL) for control studies. MVCs, anterior placental location, and uterine tenderness are associated with an increased risk of FMH, but gestational age is not.3,4 Massive fetomaternal transplacental hemorrhage causes alloimmunization in Rh incompatibility but also endangers the fetus by severe fetal anemia and resulting fetal distress and possible exsanguination. ABO incompatibility causes less severe disease.

In theory, it is possible that trauma can result in FMH as early as the fourth week of gestation, when the fetal and placental circulations first form. In practice, FMH is usually of more concern after 12 weeks' gestation, when the uterus rises above the pelvis and becomes susceptible to direct trauma.

The Kleihauer-Betke test quantifies the amount of FMH. Most laboratories screen for FMH of 5 mL or more. Unfortunately, the amount of FMH sufficient to sensitize most Rh-negative women is well below this 5-mL sensitivity level. Therefore it is advisable that all Rh-negative mothers who have a history of abdominal trauma receive one prophylactic dose of Rhesus immune globulin (RhIG) within 72 hours of the incident. In the first trimester, one 50-µg dose is sufficient because total fetal blood volume is only 4.2 mL by 12 weeks' gestation, and a 50 µg-dose covers 5 mL of bleeding. During the second and third trimesters, a 300-µg dose of RhIG is given, which protects against 30 mL of FMH. Beyond 16 weeks' gestation, the total fetal blood volume reaches 30 mL or more. Massive FMH likely exceeds the efficacy of one 300-µg dose of RhIG, so the Kleihauer-Betke test can be used to guide effective dosing.

Trauma patients at risk for massive FMH have major injuries or abnormal obstetric findings, such as uterine tenderness, contractions, or vaginal bleeding. Less than 1% of all pregnant trauma patients and only 3.1% of major trauma cases exceed the coverage of one 300-µg RhIG dose.4

Because RhIG can effectively prevent Rh isoimmunization when administered as late as after 72 hours of antigenic exposure, the results of the Kleihauer-Betke test are not immediately needed in the ED.

Mother Stable, Fetus Stable

Minor trauma does not necessarily exempt the fetus from significant injury. It is estimated that 1 to 3% of all minor trauma results in fetal loss, typically from placental abruption.11,19 Therefore, once the traumatized mother is stabilized, the focus of care is directed toward the fetus. For the viable fetus (greater than 24 weeks' gestation), monitoring is the next step. Continuous monitoring maintained throughout all diagnostic and therapeutic actions is advisable. Because direct impact is not necessary for fetoplacental pathology to occur, the traumatized pregnant woman with no obvious abdominal injury still benefits from monitoring.11

The recommended 4 hours of cardiotocographic observation of the viable fetus is extended to 24 hours if at any time during the first 4 hours there are more than three uterine contractions per hour, uterine tenderness persists, results on a fetal monitor strip are worrisome, vaginal bleeding occurs, the membranes rupture, or any serious maternal injury is present. Most cases of placental abruption after maternal trauma are detected within the first 4 hours of monitoring.11,19

On release from the hospital, the pregnant woman should be instructed to record fetal movements during the next week. If fewer than four movements per monitored hour are noted, the patient should see her obstetrician immediately and a nonstress test is warranted. The occurrence of preterm labor, membrane rupture, vaginal bleeding, or uterine pain also necessitates prompt reevaluation. Serial US and fetal heart rate tests on viable fetuses a few days after maternal trauma and periodically throughout the remaining portion of the pregnancy are helpful in monitoring fetal well-being.

Mother Stable, Fetus Unstable

Fetal death rates after maternal trauma are three to nine times higher than maternal death rates.5 If a viable fetus remains in distress despite optimization of maternal physiology, cesarean section should be considered.

Although fetal viability is first reached at 24 weeks, the ultimate determinant of the age of fetal viability is the level of neonatal care provided by the intensive care nursery unit in each hospital or accessible regional facility. Determining gestational age for fetuses of less than 29 weeks may be difficult. Emergency decisions on fetal viability are therefore made on the basis of the best US and gestational age information available.

The presence of fetal heart tones is an important survival marker for fetuses about to undergo emergency cesarean section. No infant survives if there is no fetal heart tone before emergency cesarean section commences. If fetal heart tones are present and the gestational age is 26 weeks or more, then infant survival rate may be as high as 75%.11,19

Besides fetal distress, other reasons for a cesarean section include uterine rupture, placental rupture with significant vaginal bleeding, fetal malpresentation during premature labor, and situations in which the uterus mechanically limits maternal repair. Fetal demise without any of the aforementioned conditions is not an indication for cesarean section because most will pass spontaneously within 1 week.

Mother Unstable, Fetus Unstable

If the mother's condition is critical, primary repair of her wounds is the best course. This may apply even when the fetus is in distress because a critically ill mother may not be able to withstand an additional operative procedure such as cesarean section, which prolongs laparotomy time and likely substantially increases blood loss. The best initial action on behalf of the fetus is early restoration of normal maternal physiology. If it is felt that the unstable mother can tolerate an emergency cesarean section, it should be considered for the distressed, viable fetus.11

As with nonpregnant patients, operative intervention for blunt trauma and above-the-uterus stab wounds is dictated by clinical findings and diagnostic testing results. Above-the-uterus intraperitoneal gunshot wounds require exploration.

There is little evidence to support a definitive management strategy for penetrating trauma to the gravid uterus. In situations of a hemodynamically stable mother, expectant management has been recommended. However, no prospective study has verified this. Damage to the uterus alone can be quite devastating because of its increased circulation. Without exploration, it is impossible to know the occurrence, size, or depth of uterine penetration, and there are no guidelines indicating whether a uterine wound can be left unsutured without incurring an increased risk of infection or delayed uterine rupture. Laparotomy or laparoscopy seems to be the safest means of managing penetrating uterine wounds because missed maternal injuries can quickly compromise the fragile fetus.

Perimortem Cesarean Section

Restoration of maternal and thus fetal circulation is the optimal goal. However, extended and exclusive attention to the mother in cardiopulmonary arrest may prevent recovery of a potentially viable fetus. During maternal resuscitation, adequate oxygenation, fluid loading, and a 30-degree left tilting position may improve maternal circulation. If there is no response to advanced cardiac life support, a decision for perimortem cesarean section is made. If there are no fetal heart tones, a cesarean section is not warranted.31

Perimortem cesarean section in the ED should be considered only if uterine size exceeds the umbilicus and fetal heart tones are present.11,19,31 Time since maternal circulation ceased is the critical factor in fetal outcome. Published reports support but fall short of proving that perimortem cesarean delivery should be initiated within 4 minutes of the onset of maternal cardiac arrest.19 Beyond 20 minutes, there is virtually never survival or favorable neurologic outcome for either mother or fetus.19

In the event of maternal cardiopulmonary arrest, perimortem cesarean section may be indicated. The most experienced physician available should perform the procedure as cardiopulmonary resuscitation is continuing. A midline vertical incision is made from the epigastrium to the symphysis pubis. The uterus is then entered with a midline vertical incision. If necessary, the placenta is incised to reach the fetus; once the fetus has been delivered, the cord is clamped and cut.32 Maternal revival after delivery of the fetus has been reported in a few perimortem circumstances, presumably because vena caval compression is relieved.33

Disposition

Any pregnant woman at 24 or more weeks of gestation who has sustained blunt body trauma should undergo at least 4 hours of fetal monitoring even if she looks well.11,19 Other admission and operative criteria are similar for pregnant and nonpregnant trauma patients. The emergency physician should consider the stability of the mother and the viability of the growing fetus when making management and disposition decisions.

Miscellaneous

Tetanus toxoid and immune globulin have no detrimental effect on the fetus. Proper immunization of pregnant women decreases the incidence of neonatal tetanus because the tetanus antibody crosses the placenta.

Electrical flow that bypasses the fetus has little effect on the pregnancy. Maternal elective and emergent cardioversion has been performed safely for cardiac dysrhythmias in all three stages of pregnancy. Energies up to 300 watt-seconds have been used without affecting the fetus or inducing premature labor. Cullhead reported no disruption of a monitored fetal heart rhythm during maternal cardioversion with 80 and 200 watt-seconds.34 Although the amount of energy reaching the fetal heart is thought to be small, it is advisable to monitor the fetal heart during maternal cardioversion.

Acknowledgment

The contributors would like to sincerely thank John D. G. Neufeld, MD, for his previous work on this chapter.

References

1. Tinker, SC, Reefhuis, J, Dellinger, AM, Jamieson, DJ, National Birth Defects Prevention Study. Epidemiology of maternal injuries during pregnancy in a population-based study, 1997-2005. J Womens Health (Larchmt). 2010;19:2211–2218.

2. Petrone, P, et al. Abdominal injuries in pregnancy: A 155-month study at two level 1 trauma centers. Injury. 2010;42:47–49.

3. Schiff, MA. Pregnancy outcomes following hospitalisation for a fall in Washington State from 1987 to 2004. BJOG. 2008;115:1648.

4. El-Kady, D, et al. Trauma during pregnancy: An analysis of maternal and fetal outcomes in a large population. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1661.

5. John, PR, et al. An assessment of the impact of pregnancy on trauma mortality. Surgery. 2011;149:94.

6. El Kady, D, Gilbert, WM, Xing, G, Smith, LH. Maternal and neonatal outcomes of assaults during pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:357.

7. Bochicchio, GV, Napolitano, LM, Haan, J, Champion, H, Scalea, T. Incidental pregnancy in trauma patients. J Am Coll Surg. 2001;192:566.

8. Curet, MJ, Schermer, CR, Demarest, GB, Bieneik, EJ, 3rd., Curet, LB. Predictors of outcome in trauma during pregnancy: Identification of patients who can be monitored for less than 6 hours. J Trauma. 2000;49:18.

9. Kerr, MD, Scott, DB, Samuel, E. Studies of the inferior vena cava in late pregnancy. Br Med J. 1964;1:532.

10. Archer, GW, Jr., Marx, GF. Arterial oxygen tension during apnoea in parturient women. Br J Anaesth. 1974;46:358.

11. Brown, HL. Trauma in pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 2009;114:147–160.

12. Schiff, MA, Mack, CD, Kaufman, RP, Holt, VL, Grossman, DC. The effect of air bags on pregnancy outcomes in Washington State: 2002-2005. Obstet Gynecol. 2010;115:85.

13. Hyde, LK, Cook, LJ, Olson, LM, Weiss, HB, Dean, JM. Effect of motor vehicle crashes on adverse fetal outcomes. Obstet Gynecol. 2003;102:279.

14. Klinich, KD, Schneider, LW, Moore, JL, Pearlman, MD. Investigations of crashes involving pregnant occupants. Annu Proc Assoc Adv Automot Med. 2000;44:37.

15. McGwin, G, Jr., et al. A focused educational intervention can promote the proper application of seat belts during pregnancy. J Trauma. 2004;56:1016.

16. Silverman, J, Raj, A. Intimate partner violence victimization prior to and during pregnancy among women residing in 26 U.S. states: Associations with maternal and neonatal health. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:140.

17. Guth, AA, Pachter, L. Domestic violence and the trauma surgeon. Am J Surg. 2000;179:134.

18. Hedin, LW, Janson, PO. Domestic violence during pregnancy: The prevalence of physical injuries, substance abuse, abortions and miscarriages. Acta Obstet Gyncecol Scand. 2000;79:625.

19. Sugrue, ME, O’Connor, MC, D’ Amours, SK. Trauma during pregnancy. ADF Health. 2004;5:24–28.

20. Theodorou, DA, et al. Fetal death after trauma in pregnancy. Am Surg. 2000;66:809.

21. Aboutanos, MB, et al. Significance of motor vehicle crashes and pelvic injury on fetal mortality: A five-year institutional review. J Trauma. 2008;65:616.

22. Leggon, RE, Wood, GC, Indeck, MC. Pelvic fractures in pregnancy: Factors influencing maternal and fetal outcomes. J Trauma. 2002;53:796.

23. Barraco, RD, et al. Practice management guidelines for the diagnosis and management of injury in the pregnant patient: The EAST Practice Management Guidelines Work Group. J Trauma. 2010;69:211.

24. Oyelese, Y, Ananth, CV. Placental abruption. Obstet Gynecol. 2006;108:1005.

25. Reis, PM, Sander, CM, Pearlman, MD. Abruptio placentae after auto accidents. J Reprod Med. 2000;45:6.

26. Henderson, DE, Goldman, B, Divon, MY. Ritodrine therapy in the presence of chronic abruptio placentae. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;80:510.

27. North, DL. Radiation doses in pregnant women. J Am Coll Surg. 2002;194:100–101.

28. Brown, MA, Sirlin, CB, Farahmand, N, Hoyt, DB, Casola, G. Screening sonography in pregnant patients with blunt abdominal trauma. J Ultrasound Med. 2005;24:175.

29. Ormsby, EL, Geng, J, McGahan, JP, Richards, JR. Pelvic free fluid: Clinical importance for reproductive age women with blunt abdominal trauma. Ultrasound Obstet Gynecol. 2005;26:271.

30. Damilakis, J, Perisinakis, K, Voloudaki, A, Gourtsoyiannis, N. Estimation of fetal radiation dose from computed tomography scanning in late pregnancy: Depth-dose data from routine examinations. Invest Radiol. 2000;35:527.

31. Katz, V, Balderston, K, DeFreest, M. Perimortem cesarean delivery: Were our assumptions correct? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:1916.

32. Warraich, Q, Esen, U. Perimortem caesarean section. J Obstet Gynaecol. 2009;29:690–693.

33. DePace, NL, Betesh, JS, Kotler, MN. “Postmortem” cesarean section with recovery of both mother and offspring. JAMA. 1982;248:971.

34. Cullhead, I. Cardioversion during pregnancy. Acta Med Scand. 1983;214:169.