Acute Complications of Pregnancy

Perspective

Acute complications of pregnancy can appear in all trimesters and pose challenges in diagnosis and management for the emergency physician. Life-threatening disorders, such as ectopic pregnancy in early pregnancy, pregnancy-induced hypertension in mid to late pregnancy, and abruptio placentae in late pregnancy, are relatively common. Clinicians must consider the signs and symptoms, stage of pregnancy, and hemodynamic stability of the patient in developing diagnostic and treatment strategies.

Problems in Early Pregnancy

Perspective

Miscarriage, the most common serious complication of pregnancy, is defined as the spontaneous termination of pregnancy before 20 weeks of gestation. Fetal demise after 20 weeks of gestation or when the fetus is more than 500 g is considered premature birth. Loss of early pregnancy, defined as detection of human chorionic gonadotropin (hCG) within 6 weeks of the last normal menstrual period, occurs in approximately 20 to 30% of pregnancies.1–3 Embryonic and fetal loss after implantation occurs in up to one third of detectable pregnancies. The risk of miscarriage rises with increasing maternal age (fivefold increase in those older than 40 years compared with those 25 to 29 years), increasing paternal age, alcohol use, increased parity, history of prior miscarriage, poorly controlled diabetes mellitus and thyroid disease, low pre-pregnancy body mass index, maternal stress, and history of vaginal bleeding.4–6 Approximately 80% of miscarriages occur during the first trimester; the rest occur before 20 weeks of gestation.

Threatened or actual miscarriage is a common presentation of patients in the emergency department (ED). Approximately one fourth of clinically pregnant patients experience some bleeding. It is estimated that up to 50% of all women who have bleeding during early pregnancy miscarry, although the risk is probably higher in the ED population.7,8 Patients who have a viable fetus visualized on ultrasound examination have a much lower risk of miscarriage (3-6%), although vaginal bleeding is a high-risk indicator, even when a viable fetus is present.9 Those with a history of bleeding who do not miscarry may have otherwise normal pregnancies, although they have an approximately twofold increased risk of premature birth and low-birth-weight infants.10

Principles of Disease

Pathophysiology.: The majority of miscarriages are due to either uterine malformations or chromosomal abnormalities, which account for the majority of miscarriages that occur within 10 weeks of gestation.6 In some cases the ovum never develops (anembryonic gestation). In the majority of early miscarriages, fetal death precedes clinical miscarriage, often by several weeks. Although clinical symptoms of miscarriages are most common between 8 and 12 weeks of gestation, sonographic evidence in most cases demonstrates death before 8 weeks; if fetal viability can be demonstrated by heart activity and a normal sonogram, the subsequent risk of fetal loss decreases significantly.

Maternal factors that increase the risk of miscarriage include congenital anatomic defects, uterine scarring, leiomyomas, and cervical incompetence. Other conditions associated with increased miscarriage rates include toxins (e.g., alcohol, tobacco, and cocaine), autoimmune factors, endocrine disorders, including luteal phase defects, and occasional maternal infections.2–5

Terminology.: Miscarriage can be broadly categorized into three categories. The first is a threatened miscarriage, in which the patient presents with vaginal bleeding but is found to have a closed internal cervical os. The risk of miscarriage in this population is estimated at 35 to 50%, depending on the patient's risk factors and severity of symptoms.11 If the internal cervical os is open, the miscarriage is considered inevitable. If products of conception are present at the cervical os or in the vaginal canal, the miscarriage is termed incomplete, the second classification of miscarriage. The third classification is a completed miscarriage, which occurs when the uterus has expelled all fetal and placental material, the cervix is closed, and the uterus is contracted. Establishment of the diagnosis of completed miscarriage is difficult in the ED. A gestational sac should be visualized for diagnosis because the cervix may close after an episode of heavy bleeding and clot passage without or after only partial expulsion of the products of conception. Unless an intact gestation is passed and recognized, completed miscarriage should be diagnosed only after dilation and curettage (D&C) with pathologic confirmation of gestational products, demonstration by sonography of an empty uterus with a prior known intrauterine pregnancy (IUP), or reversion to a “negative” pregnancy test result. This may take up to several weeks after the initial presentation.

Missed abortion is a relatively obsolete term referring to clinical failure of uterine growth over time. The terms anembryonic gestation (when no fetus is seen), first- or second-trimester fetal death (failure to see fetal heart activity in a fetus with at least a 5-mm crown-rump length), and delayed miscarriage are more appropriate.

Clinical Features

Patient history should include the estimated length of the gestation; time since last menstrual period; symptoms of pregnancy (including evolution or loss of pregnancy symptoms); degree of bleeding; duration of bleeding; presence of cramps, pain, or fever; and attempts by the patient to induce miscarriage. Whereas the history is important, it is not helpful in the classification of the type of miscarriage. In addition, the severity of symptoms does not correlate well with the risk of miscarriage, although cramping and passage of clots are thought more likely to occur as the miscarriage becomes inevitable.

The assessment of the patient who experiences first-trimester vaginal bleeding includes a careful abdominal examination to evaluate for tenderness or peritoneal irritation from a potential ectopic pregnancy as well as to determine uterine size (the uterus should not be palpable abdominally). Pelvic examination should be performed to evaluate whether the cervix is closed or open, to look for clots or the products of conception, and to determine the degree of vaginal bleeding as well as uterine size and tenderness. The cervix should be gently probed with a ring forceps (not a cotton-tipped applicator) to determine whether the internal os (1.5 cm deep to the external os) is open or closed. This is unnecessary in the patient who has a clearly open os or visible products of conception but can be safely performed during the first trimester as long as the forceps are used gently and do not penetrate the cervix more than 2 or 3 cm. In the patient with second-trimester bleeding, probing should not be done because the uterus is more vascular and the organized placenta may overlie the cervical os. Parous women normally have an open or lax external os, a finding of no significance. The adnexa may be enlarged, often unilaterally, either because the corpus luteum is cystic or because the pregnancy is ectopic. Significant adnexal or uterine tenderness should always raise the possibility of an ectopic pregnancy. Much less commonly, pelvic infection can cause uterine and adnexal tenderness during early pregnancy.

Any tissue that is passed should be suspended in saline or tap water (or viewed under low-power microscopy) to differentiate sloughing endometrium and organized clot from chorionic villi, which form fronds and appear feathery in the saline suspension. Except in the rare instance of heterotopic pregnancy (combined intrauterine and ectopic pregnancies), this reliably excludes ectopic pregnancy. Passage of tissue called the decidual cast in ectopic pregnancy can easily be confused with intrauterine miscarriage if the physician does not confirm the absence of chorionic villi in the tissue.12

Diagnostic Strategies

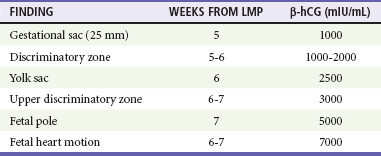

A hemoglobin level is useful to provide a baseline measurement and to evaluate the degree of blood loss in women whose bleeding persists. In addition, an Rh type should be obtained. Ultrasonography is the primary means of evaluating the health of the fetus as well as its location (Table 178-1). Because historical and clinical estimations of gestational age are often inaccurate, ultrasonography is useful to provide an accurate measure of fetal age and viability (Box 178-1).

Table 178-1

Landmarks for Gestational Age and β-hCG Level by Transvaginal Ultrasonography

β-hCG, beta subunit of human chorionic gonadotropin; LMP, last menstrual period.

Modified from Ramsey E, Shilitto J: How early can fetal heart pulsations be detected reliably using modern ultrasound equipment? Ultrasound 16:193-195, 2008.

In the stable patient with threatened miscarriage, expectant management may be sufficient to determine when intervention is needed as long as ectopic pregnancy has been excluded. Serial quantitative hCG levels are used to assess the health of the fetus if sonographic findings are indeterminate or if the gestational age is less than 6 or 7 weeks. The sonographic “discriminatory zone” is defined as the quantitative hCG level at which a normally developing IUP should reliably be seen. This is considered to be 6500 mIU/mL for transabdominal ultrasonography and 1000 to 2000 mIU/mL for transvaginal ultrasonography.13 Ultrasonography can be performed or repeated when hCG levels rise to 1500 to 3000 mIU/mL. If hCG levels are flat or decline or if sonographic criteria for fetal demise are demonstrated (see Box 178-1), the patient should be referred to an obstetrician for follow-up to ensure miscarriage completion and to rule out subsequent complications.

Differential Considerations

Ectopic pregnancy can masquerade as a threatened miscarriage in the early stages of pregnancy and should always be considered in the differential diagnosis. Even in the patient with painless vaginal bleeding, the diagnosis of ectopic pregnancy must be considered.12 Thus early ultrasonography is imperative to locate the pregnancy in the patient who has bleeding or pain.

Other diagnoses should also be considered. A small amount of bleeding occurs at the time of implantation of the blastocyst into the endometrium and occasionally at the time of the first missed menses. Molar pregnancy is also characterized by vaginal bleeding, usually during the late first trimester or the second trimester. This condition can be identified by ultrasonography. Cervical and vaginal lesions can also cause local bleeding and can usually be seen on vaginal inspection.

Management

After assessment of hemodynamic status and management of blood loss, a patient with a threatened miscarriage requires very little specific medical treatment. Anti-D immune globulin should be administered if the patient is Rh negative (unless the father is also known to be Rh negative). A 50-µg dose is used during the first trimester and a full 300-µg dose after the first trimester.14 Once ectopic pregnancy has been excluded, ultrasonography can be scheduled more routinely at a later time in the patient without significant pain as long as the patient is aware that the potential for ectopic pregnancy exists until it is excluded by identification of an IUP. In the patient who is planning pregnancy termination, prompt referral should be encouraged and chorionic villi confirmed at the time of uterine evacuation.

Unless an IUP is diagnosed, the patient with threatened miscarriage should be given careful instructions on discharge to return if she has signs of hemodynamic instability, significant pain, or other symptoms that might indicate ectopic pregnancy (so-called ectopic precautions). In conjunction with gynecologic colleagues, an ED protocol is useful to determine when follow-up sonographic evaluation and serial hCG measurements should be obtained as ultrasonography can be an inaccurate diagnostic tool if the hCG level is significantly low, if vaginal bleeding is significant, or if ultrasonographic findings do not include a fetal pole or yolk sac.15

Although 50% or more of women with threatened miscarriage who are seen in the ED ultimately miscarry, treatment to “prevent” miscarriage is not useful as most fetuses can be shown to be nonviable 1 to 2 weeks before symptoms occur. In most cases, spontaneous miscarriage is the body's natural method of expelling an abnormal or undeveloped (blighted) pregnancy. Thus a major goal of early management should be patient education and support. Patients should be advised that moderate daily activities do not affect the pregnancy. Tampons, intercourse, and other activities that might induce uterine infection should be avoided as long as the patient is bleeding, and she should return immediately for fever, abdominal pain, or a significant increase in bleeding. Cramping from a known IUP can be safely treated with oral synthetic narcotics, if needed. If the patient passes tissue, it should be brought to a provider to be examined for products of conception because differentiation of fetal parts or villi from decidual slough or casts is difficult.

Patient counseling is paramount with threatened miscarriage.16,17 Determination of fetal viability can be helpful in either reassuring the mother or preparing her for probable fetal loss. Miscarriages are associated with a significant grieving process, which is frequently more difficult because early pregnancy is unannounced and early fetal death is not publicly recognized. Because many women consider that small falls, injuries, or stress during the first trimester can precipitate miscarriage, patients should be reassured that they have done nothing to cause miscarriage. It is important to make them aware that miscarriage is common, grieving is normal, and counseling may be beneficial.18,19 A follow-up appointment should be scheduled after miscarriage to support the patient in resolving such issues.

Treatment of the patient with incomplete miscarriage includes expectant management, medical management with misoprostol, or surgical evacuation.18,20 When the miscarriage is incomplete, the uterus may be unable to contract adequately to limit bleeding from the implantation site. Bleeding may be brisk, and gentle removal of fetal tissue from the cervical os with ring forceps during the pelvic examination often slows bleeding considerably.

Management of patients with presumed completed miscarriage is more complicated. If the patient brings tissue with her, this should be sent to the pathology department for evaluation. Unless an intact gestational sac or fetus is visualized, it is rarely clear clinically whether miscarriage is “complete.” Studies have shown that in women with a history consistent with miscarriage who have minimal remaining intrauterine tissue as determined by ultrasonography, expectant management is safe, but only if ectopic pregnancy can be excluded.20 If endometrial tissue is not seen with ultrasonography, bleeding is mild, and gestational age is less than 8 weeks, curettage is frequently unnecessary and the patient can be safely observed by a gynecologist for serial hormonal assays. Up to 80% of women with first-trimester miscarriage complete the miscarriage without intervention.21 However, the need for later visits and procedures may be decreased by uterine curettage, particularly if the fetal pole or a gestational sac is visible on the sonogram at the time of evaluation.20 Medical management with misoprostol instead of D&C is also an option and has a success rate of up to 96%.18,22,23 The patient should be instructed to return if uncontrolled bleeding, severe pain or cramping, fever, or tissue passage occurs. Follow-up is recommended in 1 or 2 weeks to ensure that the miscarriage is complete.

After miscarriage, the patient should be advised that fetal loss, even during the first trimester, can cause significant psychological stress.16 Follow-up in 1 or 2 weeks with a gynecologist should be provided. Some physicians prescribe antibiotics after D&C (usually doxycycline or metronidazole), particularly in populations of patients at high risk for genital tract infections. Ergonovine or methylergonovine (0.2 mg orally twice daily) can be used to stimulate uterine involution. The patient should be advised to return if signs of infection (fever or uterine tenderness) occur, if bleeding resumes, or if further tissue is passed.

Ectopic Pregnancy

Ectopic pregnancy, or pregnancy implanted outside the uterus, is an increasingly frequent problem that poses a major health risk to women during the childbearing years. It is the third leading cause of maternal death, responsible for 6% of maternal mortality.24 The incidence of ectopic pregnancy has risen steadily during several decades and now accounts for approximately 2% of all pregnancies. Although the incidence of ectopic pregnancy is highest in women aged 25 to 34 years, the rate is highest among older women and women belonging to minority groups. Simultaneous intrauterine and extrauterine gestations (heterotopic pregnancy) have historically been rare, occurring in approximately 1 in 4000 pregnancies; more recently, women who have undergone assisted reproduction techniques with embryo transfer have demonstrated a risk of one of the pregnancies being ectopic of 4% or greater. The incidence of ectopic pregnancy among women presenting to the ED with vaginal bleeding or pain in the first trimester is consistently approximately 10% in several series.25,26

Principles of Disease

Implantation of the fertilized ovum occurs approximately 8 or 9 days after ovulation. Risk factors for an abnormal site of implantation include prior tubal infection (50% of cases), anatomic abnormalities of the fallopian tubes, and abnormal endometrium (host factors). These result in failure of the embryo to implant in the endometrium. The risk of ectopic pregnancy increases approximately threefold after a patient has had pelvic inflammatory disease (PID). In recent studies, one fourth of patients with ectopic pregnancies have had tubal surgery, including tubal sterilization or removal of ectopic pregnancy.27 If the patient is currently using an intrauterine device, increased risk can occur from complicating PID or from failure of the intrauterine device to prevent pregnancy while preventing endometrial implantation. All forms of contraception except the intrauterine device and tubal sterilization decrease the incidence of ectopic pregnancy. After an ectopic pregnancy, the risk of a subsequent ectopic pregnancy was 22% in one series of women trying to conceive again (Box 178-2).28

When abnormal implantation occurs in the fallopian tubes, on the ovaries, or in the cervix, the pregnancy usually grows at a less than normal rate, which can result in abnormally low or declining hCG production. Blood leaks intermittently through the tubal wall or out the fimbrial ends, with spillage into the peritoneal cavity. Bleeding and other symptoms are usually intermittent. Three outcomes are possible: spontaneous involution of the pregnancy, tubal abortion into the peritoneal cavity or vagina, or rupture of the pregnancy with internal or vaginal bleeding. Implantation in the uterine horn (cornual pregnancy) is particularly dangerous because the growing embryo can use the myometrial blood supply to grow larger (10-14 weeks of gestation) before rupture occurs.

Clinical Features

The classic clinical picture of ectopic pregnancy is a history of delayed menses, followed by abdominal pain and vaginal bleeding in a patient with known risk factors. Unfortunately, this history is neither sensitive nor specific. Risk factors for ectopic pregnancy are absent in almost half of patients. Fifteen percent to 20% of patients with symptomatic ectopic pregnancy have not missed a menstrual period, and occasionally the patient has no history of vaginal bleeding. Abdominal pain is most commonly severe, peritoneal in nature, and constant. Shoulder pain implies free fluid in the peritoneal cavity and is suggestive of an ectopic pregnancy with significant hemorrhage. The pain of ectopic pregnancy can also be crampy, intermittent, or even absent.12,29

The physical examination findings in ectopic pregnancy are likewise variable. Vaginal bleeding, uterine or adnexal tenderness, or both in the patient with a positive pregnancy test result should trigger consideration of ectopic pregnancy. Tachycardia is not always present, even with significant hemoperitoneum; hemoglobin level is usually normal, and hypotension may be seen.29 The presence of peritoneal signs, cervical motion tenderness, or lateral or bilateral abdominal or pelvic tenderness indicates increased likelihood of an ectopic pregnancy. If significant peritoneal irritation is present, pain can preclude accurate bimanual examination. Adnexal masses are felt in only 10 to 20% of patients with ectopic pregnancy.12,29 Vaginal bleeding is often mild. Heavy bleeding with clots or tissue usually suggests a threatened or incomplete miscarriage, although the patient with an ectopic pregnancy who has decreasing hormonal levels may experience endometrial sloughing, which can be mistaken for passage of fetal tissue. Passed tissue should be examined, as with cases of miscarriage, in tap water or saline (or under low-power microscopy). Unless fetal parts or chorionic villi are seen, ectopic pregnancy should not be excluded in the patient with bleeding or passage of “tissue.”

Diagnostic Strategies

Because both the history and the physical examination of the patient with ectopic pregnancy are insensitive and nonspecific, ancillary studies are essential to locate the pregnancy in any patient who has abdominal pain or vaginal bleeding and a positive pregnancy test result. Technologic advances have allowed accurate detection or exclusion of ectopic pregnancy in the assessment of the woman with first-trimester vaginal bleeding or pelvic pain. Ultrasonography and hormonal assays are the most commonly used ancillary tests. Laparoscopy may be the most efficient diagnostic tool in some instances.

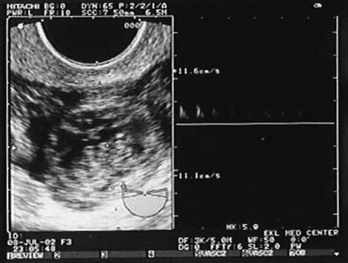

Ultrasonography.: Ultrasonography is the primary method used to locate early gestation, to establish gestational age, and to assess fetal viability. Transabdominal ultrasonography is most useful for identification of IUPs with fetal heart activity and exclusion of ectopic pregnancy (except in patients at high risk for heterotopic pregnancy because of infertility procedures).13 Transvaginal ultrasonography is more sensitive, recognizes IUP earlier than transabdominal ultrasonography does, and is diagnostic in up to 80% of stable patients presenting in the first trimester.30

Sonographic findings in the patient with suspected ectopic pregnancy are listed in Box 178-3 and illustrated in Figures 178-1 to 178-5. In general, an indeterminate ultrasound study usually does not result in a diagnosis of normal pregnancy; one series of more than 1000 pelvic ultrasound examinations reported that 53% of indeterminate ultrasound studies resulted in a diagnosis of embryonic demise, 15% were ectopic pregnancies, and only 29% had an IUP.31 However, correlation of sonographic results with quantitative hCG measurements can add to the predictive value.32 With hCG levels of less than 1000 mIU/mL, the risk of ectopic pregnancy increases fourfold; ultrasonography is still diagnostic in a significant minority of patients (one third of patients with ectopic pregnancy), although the accuracy of sonographic findings may decrease.31 Normal pregnancy is unlikely if no gestational sac is seen by transvaginal ultrasonography with an hCG level higher than 1000 to 2000 mIU/mL, depending on the institution's discriminatory zone, but the differential diagnosis includes both miscarriage and ectopic pregnancy. Unfortunately, levels of approximately 1500 mIU/mL develop in only approximately half of patients with ectopic pregnancies (see Table 178-1).8,13

Figure 178-1 Pregnancy in the fallopian tube, diagnostic of an ectopic pregnancy. (Courtesy Mary Ann Edens, MD.)

Figure 178-2 Fetal heart movements detected by ultrasonography in the fallopian tube, diagnostic of an ectopic pregnancy. (Courtesy Mary Ann Edens, MD.)

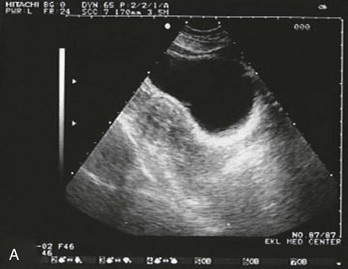

Figure 178-3 Ultrasonography showing an empty uterus, indeterminate for diagnosis of an ectopic pregnancy. (Courtesy Mary Ann Edens, MD.)

Figure 178-4 Ultrasonography showing fluid around the fallopian tube. (Courtesy Mary Ann Edens, MD.)

Indeterminate sonograms, which demonstrate neither an IUP nor extrauterine findings suggestive of ectopic pregnancy, occur in approximately 20% of ED evaluations of women with first-trimester bleeding or pain. Ectopic pregnancy is more likely among this subgroup with indeterminate sonograms if the hCG level is less than 1000 mIU/mL and when the uterus is empty. Endometrial debris and fluid in the uterus do not exclude ectopic pregnancy.33

Use of bedside ultrasonography in the ED for the diagnosis of IUP and the exclusion of ectopic pregnancy has shown good sensitivity and negative predictive value in ruling out ectopic pregnancy, but it requires significant operator training.34–38 In addition to operator-based limitations, it is also limited by device availability and quality within the ED.

Hormonal Assays.: The quantitative hCG levels have two primary uses: serial levels can be used in the stable patient who can be observed as an outpatient, and a single level can be correlated with sonographic results for improved interpretation. Serum hCG levels normally double every 1.8 to 3 days for the first 6 or 7 weeks of pregnancy, beginning 8 or 9 days after ovulation. An initial quantitative level can be measured at the time of the ED visit, particularly if the sonogram is indeterminate or the gestational age is estimated as less than 6 weeks. A repeated level should be measured 48 to 72 hours later. Levels that fall or rise slowly are associated with abnormal pregnancy, either intrauterine or ectopic. Twenty-one percent of women with an ectopic pregnancy in one series had an initial rise in hCG at a rate consistent with an IUP.36

Single quantitative hCG levels can also be useful in conjunction with ultrasonography; normal IUPs should be visible transvaginally at 1000 to 2000 mIU/mL hCG or higher (see Table 178-1). A benign course for ectopic pregnancy cannot be assumed with low hCG levels; ruptured ectopic pregnancies requiring surgery have been reported with very low or absent levels of hCG.39

Serum progesterone levels have been studied as an additional or alternative marker to determine which patients need further evaluation and follow-up for possible ectopic pregnancy. Progesterone rises earlier than hCG in normal pregnancy and plateaus with levels higher than 20 ng/mL, so measurement of serial levels over time is not necessary. Levels below 5 ng/mL exclude viable IUP (with rare exceptions) and could be useful when hCG levels are low, ultrasonography is indeterminate, and the clinician is considering D&C or laparoscopy. The ability of a progesterone level to differentiate ectopic pregnancy from a failed IUP is limited, however, and it is not a standard tool for ED evaluation.

Other Ancillary Studies.: Dilation and evacuation can be used in patients without a viable IUP or ectopic pregnancy on ultrasonography to differentiate intrauterine miscarriage from ectopic pregnancy. Identification of chorionic villi in endometrial samples is seen in approximately 70% of patients and excludes ectopic pregnancy (except in infertility patients). Identification of chorionic villi can be made even in 50% of women with an empty uterus on ultrasonography and limits the need for laparoscopy to exclude ectopic pregnancy in this population.40

Although it is invasive, laparoscopy is extremely accurate as a diagnostic (and therapeutic) procedure for possible ectopic pregnancy. It is the diagnostic treatment of choice in the unstable first-trimester patient with frank peritoneal signs and is also indicated in patients with significant peritoneal fluid or an ectopic gestation in the pelvic cavity. Medical alternatives for management of ectopic pregnancy have resulted in decreased indications in stable patients.32,41

Differential Considerations

The spectrum of clinical presentations in ectopic pregnancy is wide, so the differential diagnosis includes essentially all first-trimester complications. Threatened miscarriage, the most common alternative diagnosis, can be recognized by sonographic evidence of an IUP, either healthy or failed. Hypovolemia may be seen, particularly in incomplete miscarriage, but hypotension without significant vaginal hemorrhage is highly suggestive of ectopic pregnancy. Identification of fetal parts or chorionic villi in tissue expelled or obtained during D&C is useful to confirm a complication of IUP, although this is not sufficient to exclude ectopic pregnancy in the patient who has received infertility treatment and has an increased risk of heterotopic gestation.

A ruptured corpus luteum cyst should also be considered in the patient who has first-trimester bleeding associated with peritoneal pain or irritation. The corpus luteum normally supports the pregnancy during the first 7 or 8 weeks. Rupture causes pelvic pain and peritoneal irritation. Ultrasonography is helpful if it reveals an IUP (except in patients with in vitro fertilization). During early gestation, when ultrasonography is nondiagnostic, free fluid is usually visible by ultrasonography, and serial observation may be required (see Fig. 178-4). If the patient is unstable (especially if an IUP cannot be identified by ultrasonography), laparoscopy or, rarely, laparotomy may be required to differentiate between the two conditions.

Management

Classically, approximately 20% of women with ectopic pregnancies manifest signs and symptoms warranting immediate intervention.41 This includes patients with significant hypovolemia, large amounts of peritoneal fluid, or an open cervical os. For patients with significant signs of hypovolemia, rapid volume resuscitation should be instituted with intravenous fluids and blood products as necessary, and a baseline hemoglobin level and type and crossmatch should be obtained. A D&C or evacuation procedure with examination of endometrial contents for products of conception can be performed urgently in the unstable patient with an open cervical os.

If the patient remains unstable, immediate surgery is warranted. Laparoscopy may be indicated for patients who stabilize with treatment or for those who are hemodynamically stable but exhibit significant peritoneal signs. One study reported that identification of free fluid in Morison's pouch on bedside ultrasonography predicted the need for operative intervention in the majority of cases in patients with suspected ectopic pregnancies.26 All patients with ectopic pregnancy who are Rh negative should be given Rh immune globulin 50 µg intramuscularly, unless the father is known to be Rh negative.

The majority of patients who seek treatment for bleeding or pain during the first trimester of pregnancy are stable. In such patients, the goal should be to exclude ectopic pregnancy in a timely manner. In the patient with significant pain by history or examination or significant risk factors for ectopic pregnancy, ultrasonography should be performed before discharge. If the results are indeterminate, a quantitative hCG level may be helpful in determining the patient's risk for ectopic pregnancy.

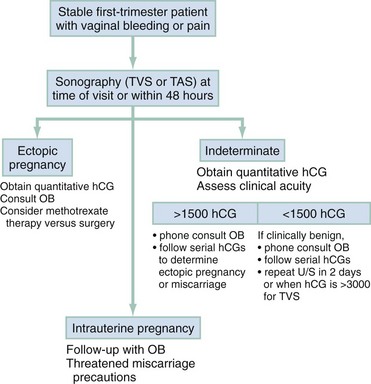

In low-risk patients with only minor symptoms or bleeding, ectopic pregnancy is still a possibility. Two general outpatient approaches can be considered. In most institutions, ultrasonography is the initial screening tool (Fig. 178-6). If an IUP is not seen, quantitative hCG levels help stratify patients by risk. In all cases, if the patient is discharged, careful instructions are given for symptoms that would require her earlier return (ectopic precautions).

Figure 178-6 Management of vaginal bleeding or pain in the stable first-trimester pregnant patient. hCG, human chorionic gonadotropin; OB, obstetrics specialist; TAS, transabdominal sonography; TVS, transvaginal sonography; U/S, ultrasonography.

An alternative strategy uses hCG levels first. However, waiting times for the serum assay can increase ED length of stay. In addition, ultrasonography is usually diagnostic of IUP or ectopic pregnancy, even if the hCG level is less than 1000 mIU/mL.29,30 In most hands, the initial sonogram provides more rapid and accurate information.

A significant minority of patients have indeterminate sonographic results and hCG levels below 1000 mIU/mL. When the hCG levels never rise to the discriminatory zone, the differential diagnosis includes intrauterine fetal demise and ectopic pregnancy. Early D&C with identification of products of conception can be useful in the patient with nonrising hCG levels to detect chorionic villi and to confirm a failed IUP or to strongly suggest ectopic pregnancy.40 Alternatively, hCG levels can be followed until they reach zero, particularly if initial levels are low.

Although laparotomy may be required for patients who have ectopic pregnancies, an increasing number of surgeries are being performed through the laparoscope. Salpingostomy is preferred to salpingectomy if the patient is stable and the procedure is technically feasible. Overall, the advent of transvaginal ultrasonography has resulted in a decreased number of surgeries and a trend toward nonoperative management.42

Medical management has become standard in many areas for the stable patient with minimal symptoms and is cost-effective when subsequent fertility is being considered.41 Methotrexate is the drug most commonly used to treat early ectopic pregnancy. It causes destruction of rapidly dividing fetal cells and involution of the pregnancy. Medical treatment is most often used for patients who are hemodynamically stable with a tubal mass smaller than 3.5 cm in diameter, no fetal cardiac activity, and no sonographic evidence of rupture. Although there is no agreed on cutoff for single-dose methotrexate, a systematic review found that patients with an hCG level above 5000 mIU/mL had an increased failure rate.43 Medical therapies are associated with an 85 to 93% success rate, with no significant difference between single- and multiple-dose protocols.44 Pelvic pain is common (60%) in patients receiving methotrexate, even when it is used successfully.45 Indications of methotrexate failure and need for rescue surgery include decreasing hemoglobin levels, significant pelvic fluid, and unstable vital signs. All patients receiving methotrexate require close follow-up until the hCG level reaches zero, which may take 2 or 3 months.

Molar Pregnancy

Molar pregnancy, also known as gestational trophoblastic disease, comprises a spectrum of diseases characterized by disordered proliferation of chorionic villi. In the absence of fetal tissue, the pregnancy is termed a complete hydatidiform mole. More rarely, if fetal tissue is present and trophoblastic hyperplasia is focal, it is called an incomplete mole. In approximately 19% of molar pregnancies, neoplastic gestational disease develops, with persistence of molar tissue after the pregnancy has been evacuated.46,47 Metastatic disease can develop, requiring chemotherapy and intensive oncologic management.

Early molar pregnancy is usually not clinically apparent. The most well described risk factor for development of a molar pregnancy is extremes of maternal age.48 Many patients present with abdominal pain, nausea and vomiting, or vaginal bleeding, and it may be difficult to differentiate these patients from those with threatened miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy by historical features alone.49 Patients sometimes seek treatment for apparent persistent hyperemesis gravidarum from high circulating levels of hCG, bleeding or intermittent bloody discharge, or respiratory distress; failure to hear fetal heart tones during the second trimester is the usual initial clue to diagnosis.50,51 If molar pregnancy spontaneously aborts, it is usually in the second trimester (before 20 weeks), and the patient or physician may note passage of grapelike hydatid vesicles. Uterine size is larger than expected by date (by more than 4 weeks) in approximately 30 to 40% of patients. Theca lutein cysts may be present on the ovaries as a result of excessive hormonal stimulation, and torsion of affected ovaries can be seen.50,51

The diagnosis of hydatidiform mole is based on the characteristic sonographic appearance of hydropic vesicles within the uterus, described as a “snowstorm” appearance (Fig. 178-7). Alternatively, cystic changes are seen in partial molar pregnancies. In some cases, partial molar pregnancy is detected only on pathologic examination of abortion specimens.52 Complications of molar pregnancy include preeclampsia or eclampsia (which can develop before 24 weeks of gestation), pulmonary embolization of trophoblastic cells, hyperemesis gravidarum, and significant uterine bleeding, either acute or chronic. Ultrasonography usually provides the diagnosis of complete molar pregnancy, either in the second-trimester patient who has “threatened miscarriage” or during sonographic assessment for fetal well-being and size. However, ultrasonography is only 58% sensitive, and diagnosis of partial mole is made in 17% of cases.52 Up to two thirds of molar pregnancies are diagnosed by pathologic specimens after miscarriage.52

Complications of Late Pregnancy

Vaginal Bleeding in Later Pregnancy

Perspective

Bleeding during the second half of pregnancy occurs in approximately 4% of pregnancies. Only 20% of miscarriages occur after the first trimester, and the most important differential diagnoses after 12 to 14 weeks of gestation are abruptio placentae and placenta previa. The cause is often not determined, although occult marginal placental separations (which can be recognized only by placental inspection at delivery) are held to be a common source of bleeding from above the cervix. Other causes of late vaginal bleeding include early labor, various cervical and vaginal lesions, lower genital tract infections, and hemorrhoids.

Bleeding during the second trimester before the fetus is potentially viable (14-24 weeks) is not benign. One third of fetuses are ultimately lost when maternal bleeding occurs. Management is supportive and expectant because fetal rescue is impossible at this level of fetal immaturity. In the third trimester, vaginal bleeding is still associated with significant morbidity in approximately one third of women, but the treatment includes consideration of urgent delivery.53

Abruptio Placentae

Principles of Disease.: Abruptio placentae, or separation of the placenta from the uterine wall, is believed to account for approximately 30% of episodes of bleeding during the second half of pregnancy. In addition, small subclinical or marginal separations may go undetected until the placenta is examined at delivery and probably account for many of the other self-limited episodes of bleeding for which no diagnosis is made. In cases of nontraumatic abruptio placentae, apparently spontaneous hemorrhage into the decidua basalis occurs, causing separation and compression of the adjacent placenta. Small amounts of bleeding may be asymptomatic and remain undetected until delivery. In other instances, the hematoma expands and extends the dissection; bleeding may be concealed or may be clinically apparent if dissection occurs along the uterine wall and through the cervix. Placental separation can be acute or an indolent problem throughout late pregnancy.

Abruptio placentae is most clearly associated with maternal hypertension and preeclampsia; it is also more common with increasing maternal age and parity, history of smoking, thrombophilia, prior miscarriage, prior abruptio placentae, and cocaine use.53,54 Placental separation can also be associated with blunt trauma to the abdomen. In such instances, the cause appears to be shearing of a nonelastic placenta from the easily distorted elastic uterine wall at the time of traumatic impact. Women who reported physical violence during pregnancy were twice as likely as women who did not report violence to have an abruption.55

Clinical Features.: Vaginal bleeding occurs in 70% of patients with abruptio placentae.55 Blood is characteristically dark and the amount is often insignificant, although the mother may have hemodynamic evidence of significant blood loss. Uterine tenderness or pain is seen in approximately two thirds of women; uterine irritability or contractions are seen in one third. With significant placental separation, fetal distress occurs and the maternal coagulation cascade may be triggered, causing disseminated intravascular coagulation.53

There is a wide spectrum of severity of symptoms and risk in placental separation. Up to 20% of women will have no pain or vaginal bleeding.54 Assessment is generally based on clinical features, coagulation parameters, and signs of fetal distress. Slight vaginal bleeding, little or no uterine irritability, absence of signs of fetal distress, and normal coagulation characterize mild abruption. As the separation becomes more extensive, it is associated with more vaginal bleeding (or hidden maternal blood loss), increased uterine irritability with or without tetanic contractions, declining fibrinogen levels, and evidence of fetal distress and maternal tachycardia. In cases of severe abruptio placentae (15% of cases), the uterus is tetanically contracted and very painful, maternal hypotension results from visible or concealed uterine blood loss, fibrinogen levels are less than 150 mg/dL, and fetal death can occur. Ultrasonography is insensitive in the diagnosis of abruptio placentae, often because the echogenicity of fresh blood is so similar to that of the placenta. Symptomatic or even fetus-threatening abruption can occur in the presence of a normal sonogram.53

Fetal distress and death occur in approximately 15% of patients with abruptio placentae by interruption of placental blood and oxygen flow. Risk of fetal death increases in proportion to both the percentage of placental surface involved and the rapidity of separation. Fetal distress may result from the loss of placental blood flow, associated maternal hemorrhage (into the uterine cavity or externally), increased uterine tone, or resultant disseminated intravascular coagulation. Maternal death can result, usually from coagulopathy or exsanguination. Fetomaternal transfusion occurs in a significant minority of patients. Placental separation also predisposes the mother to amniotic fluid embolism.

Differential Considerations.: The main alternative diagnosis in the woman with late-pregnancy bleeding is placenta previa, which is usually associated with painless, bright red bleeding and must be excluded with ultrasonography. Lower genital tract or rectal lesions and bloody show (blood-tinged cervical mucous plug) are also considerations.

In the patient with abdominal pain but no vaginal bleeding, abruptio placentae with concealed hemorrhage must be distinguished from other causes of abdominal pain in later pregnancy: complications of preeclampsia, pyelonephritis, various liver diseases, gallbladder disease, appendicitis, and ovarian torsion. Uterine irritability caused by abruptio placentae can also be confused with early labor; in one series, almost one fourth of patients were misdiagnosed as having premature labor until fetal distress occurred. If the patient has acute catastrophic hypotension, amniotic fluid embolus (with or without abruptio placentae) and uterine rupture must be considered.53

Placenta Previa

Principles of Disease.: Placenta previa, or implantation of the placenta over the cervical os, is the other major cause of bleeding episodes during the second half of pregnancy. The risk of placenta previa is increased with maternal age, multiparity, cesarean section, and preterm labor.56 Bleeding occurs when marginal placental vessels implanted in the lower uterine segment are torn, either as the lower uterine wall elongates or with cervical dilation near the time of delivery. Early bleeding episodes tend to be self-limited unless separation of the placental margin is aggravated by iatrogenic cervical probing or onset of labor.

Clinical Features.: Painless, fresh vaginal bleeding is the most common symptom of placenta previa. In approximately 20% of cases, some degree of uterine irritability is present, but this is usually minor. Vaginal examination usually reveals bright blood from the cervical os. Digital or instrumental probing of the cervix should never be done during the second half of pregnancy because it can precipitate severe hemorrhage in the patient with an asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic placenta previa. In the ED, speculum examination of the vagina and cervix should be performed only in those settings in which obstetric consultation is not readily available. It should be limited to an atraumatic partial speculum insertion to identify whether the bleeding is coming from the cervical os (and a presumed placenta previa), hemorrhoids, or a vaginal lesion that might not require urgent management.

Most cases of placenta previa identified during the midtrimester resolve by the time of delivery as the lower uterine segment elongates and the placenta no longer overlaps the cervical os. Central or total previa (which occurs in approximately 20% of cases) can, however, cause severe hemorrhage, with risk of exsanguination for the fetus and mother.

Diagnostic Strategies.: Ultrasonography is the diagnostic procedure of choice for localization of the placenta and diagnosis of placenta previa. Accuracy is excellent; visualization of the placenta as well as of the internal cervical os is required. The bladder should be emptied before examination for suspected placenta previa to avoid overdiagnosis of placenta previa. Transvaginal ultrasonography is safe and even more accurate for visualization of the relationships between the placenta and the internal os.57

Management

Patients who experience vaginal bleeding during late pregnancy should have immediate obstetric consultation and arrangements for safe transfer to an appropriate obstetric facility. Initial management consists of maternal stabilization, with establishment of two large-bore intravenous lines and fluid resuscitation, as well as continuous fetal monitoring if it is available. A baseline hemoglobin level should be obtained, and blood should be sent for type and crossmatch; baseline coagulation studies including platelet count, prothrombin time, and partial thromboplastin time should be performed; and fibrinogen level and the presence of fibrin split products should be determined. The normal fibrinogen level in pregnancy is 400 to 450 mg/dL; values below 300 mg/dL indicate significant consumption of coagulation factors.

Blood loss requiring transfusion can occur in patients with placenta previa or abruptio placentae. Fresh frozen plasma or fresh whole blood may be needed because of the coagulopathy associated with significant abruptio placentae. Fetomaternal hemorrhage can occur with abruption. If the Rh-negative patient has not yet received her routine Rh immune globulin prophylaxis at 28 weeks, 300 µg of Rh immune globulin should be administered within 72 hours (unless the father is known to be Rh negative).58 Transfer to the obstetric unit should be expedited if the patient is stable, or it should be done after initiation of resuscitation if she is unstable. If transfer to another hospital is required, a high-risk transfer team should be used if bleeding is significant or if the fetus is in distress. Although the bleeding source may not be identified or may be relatively benign, assessment is best accomplished by obstetricians who are accustomed to evaluation of late-pregnancy complications and who can perform emergent cesarean section if it is needed.

In the obstetrics unit, fetal monitoring is continued. Ultrasonography is used primarily to locate the placenta and to diagnose placenta previa; it may not be reliable in confirming the diagnosis of abruptio placentae. On occasion, subplacental hemorrhages of abruptio placentae can be seen and changes in size of the collection can be monitored. If evidence of placenta previa is absent or equivocal, vaginal examination is performed in the delivery suite, where emergency cesarean section can be performed if uncontrolled bleeding is encountered.

Patients who have significant abruptio placentae may require early delivery (either vaginal or surgical, depending on fetal status). If placenta previa is diagnosed or if abruptio placentae is considered mild, the patient is admitted for close monitoring. The goal is to support the patient, ideally until fetal maturity is demonstrated and a successful delivery can be accomplished.

Pregnancy-Induced Hypertension (Preeclampsia and Eclampsia)

Hypertension is observed in approximately 6 to 8% of pregnancies and is generally divided into several categories.59 Gestational hypertension occurs during pregnancy, resolves during the postpartum period, and is recognized by a new blood pressure reading of 140/90 mm Hg or higher. Preeclampsia is gestational hypertension with proteinuria (>300 mg/24 hr), and eclampsia is the occurrence of seizures in the patient with signs of preeclampsia. Progression of preeclampsia to eclampsia is unpredictable and can occur rapidly. Pregnancy-aggravated hypertension is chronic hypertension with superimposed preeclampsia or eclampsia. Chronic or coincidental hypertension is present before pregnancy or persists more than 6 weeks postpartum.59

Approximately 2 to 7% of pregnancies are complicated by pregnancy-induced hypertension. The incidence of actual eclampsia has progressively declined, but it is still one of the major causes of maternal mortality. The risk of pregnancy-induced hypertension is greatest in women younger than 20 years; primigravidas; those with twin or molar pregnancies; those with hypercholesterolemia, pregestational diabetes, or obesity; and those with a family history of pregnancy-induced hypertension.60

Principles of Disease

Gestational hypertension/preeclampsia is a vasospastic disease of unknown cause unique to pregnant women. Vasospasm, ischemia, and thrombosis associated with preeclamptic changes cause injury to maternal organs, placental infarction and abruption, and fetal death from hypoxia and prematurity. The cause of eclampsia is not known, but recent research has centered on vascular responsiveness to endogenous vasopressors in the preeclamptic woman. Vascular responsiveness is normally depressed during pregnancy, which is a high-output, low-resistance state. Gestational hypertension is characterized by an even greater elevation in cardiac output, followed by an abnormally high peripheral resistance as clinical manifestations of the disease develop. In patients with preeclampsia, the cardiac output eventually drops as peripheral resistance rises.61 The cause of these changes is not known, but endothelial dysfunction is purported to release vasoactive mediators and to result in vasoconstriction.62 Antiplatelet agents during pregnancy have been reported to reduce the risk of development of preeclampsia, supporting the premise of an imbalance between levels of thromboxane and prostacyclin in preeclampsia.63

The vasospastic effects of gestational hypertension/preeclampsia are protean. Intravascular volume is lower than in normal pregnancy, central venous pressures are normal, and capillary wedge pressures are variable. Liver effects are believed to be due to hepatocellular necrosis and edema resulting from vasospasm. Renal injury causes proteinuria and may result in decreased glomerular filtration. Microangiopathic hemolysis may result from vasospasm, causing thrombocytopenia. Central nervous system effects include microvascular thrombosis and hemorrhage as well as focal edema and hyperemia.60

Clinical Features

Signs and Symptoms.: The patient with gestational hypertension has mild systolic or diastolic blood pressure elevation, no proteinuria, and no evidence of organ damage. Mental status assessment, testing of reflexes, abdominal examination, liver function studies, and coagulation studies should yield normal results. Preeclampsia is associated with kidney changes and, in severe cases, other end-organ symptoms. Edema is often difficult to assess because pregnancy is normally associated with excess extracellular fluid and dependent edema, and it is no longer used as a criterion for preeclampsia. Proteinuria (300 mg/24 hr) is variable at any given time and may not be detectable in a random urine specimen.59

In cases of severe preeclampsia, diastolic blood pressure can exceed 110 mm Hg, proteinuria is more severe, and there is evidence of vasospastic effects in various end organs. Central nervous system effects commonly include headache or visual disturbances. Thrombocytopenia may be present, liver function test findings may be elevated, and the liver is often tender. Renal dysfunction may be indicated by oliguria and elevated creatinine levels in addition to proteinuria.

Complications.: The HELLP syndrome, a particularly severe form of preeclampsia that develops in 5 to 10% of women who have preeclamptic symptoms, is characterized by hemolysis, elevated liver enzymes, and low platelet count (100,000/mL). Prothrombin time, partial thromboplastin time, and fibrinogen level are normal, and blood studies reveal microangiopathic hemolytic anemia. Other complications of preeclampsia include spontaneous hepatic and splenic hemorrhage and abruptio placentae.

The most dangerous complication is eclampsia, which is the occurrence of seizures or coma in the setting of signs and symptoms of preeclampsia. Warning signs for development of frank eclampsia include headache, nausea and vomiting, and visual disturbances.64 Elevated total leukocyte count, creatinine, and aspartate aminotransferase are also predictive of increased morbidity for the patient with severe preeclampsia.65 Particularly in early eclampsia before 32 weeks of gestation, seizures may develop abruptly and hypertension may not be associated with edema or proteinuria.66 In postpartum women who have eclampsia, more than half (55%) are not previously diagnosed with preeclampsia, and patients may present with headache, vision changes, elevated blood pressure, or seizure up to 4 weeks after delivery.67 After 48 hours postpartum and without predelivery signs of preeclampsia, other diagnoses, such as intracranial hemorrhage, should be considered. Maternal complications of eclampsia include permanent central nervous system damage from recurrent seizures or intracranial bleeding, renal insufficiency, and death.

The maternal mortality rate from eclampsia has been reduced with modern management and is currently less than 1%. Perinatal mortality has also decreased, although it remains 4 to 8%.60 Causes of neonatal death include placental infarcts, intrauterine growth retardation, and abruptio placentae. In addition, fetal hypoxia from maternal seizures and the complications of premature delivery contribute significantly to fetal mortality and morbidity.

Diagnostic Strategies

The patient who has severe preeclampsia should have an intravenous line and fetal monitoring initiated in a quiet but closely observed area. Blood testing should include complete blood cell count, renal function studies, liver function tests, platelet count, and coagulation profile. A baseline magnesium level should also be obtained. In the patient with actual seizures, serum glucose concentration should be tested. If a history of preeclampsia is not obtained or the symptoms are refractory to magnesium sulfate therapy, a computed tomography (CT) scan of the head should be performed to exclude cerebral venous thrombosis or an intracranial bleed, either of which can occur in pregnancy (with or without pregnancy-induced hypertension) and may require specific treatment. CT scan abnormalities can be seen in half of patients with eclampsia. Patchy hemorrhage and microinfarcts of the cortex are characteristic and may be due to loss of cerebral autoregulation in patients with severe pregnancy-related hypertension. Diffuse cerebral edema can also be seen.68

Differential Considerations

Peripheral edema is common in normal pregnancy, and it may be difficult to differentiate normal edema from that of early preeclampsia. Differentiation of gestational hypertension from preexistent hypertension is often impossible if no record of normal blood pressure is available. Seizures during pregnancy may be due to epilepsy as well as other intracranial catastrophes, such as thrombosis or hemorrhage.

Management

In the patient who has mild preeclampsia, appropriate management includes documentation of blood pressure and reflexes, weight, and testing to ensure normal end-organ function. Accurate determination of gestational age by ultrasonography is needed to allow optimal management if symptoms progress. Limitation of physical activities (including bed rest) is the only demonstrated means of reducing blood pressure and allowing the pregnancy to be sustained longer. Definitive treatment is delivery of the fetus, although expectant management is standard in women at less than 34 weeks of gestation. Arrangement for close follow-up is important for patients who are not hospitalized.

Hospitalization is usually required for patients with sustained hypertension above 140/90 mm Hg and signs of severe preeclampsia. Baseline laboratory studies to identify end-organ effects in the liver, kidney, and hematologic systems should be obtained. Both diuresis and antihypertensive therapy have been remarkably unsuccessful in improving fetal outcome or prolonging pregnancy. Admission does, however, allow the obstetrician to accurately assess fetal age and well-being, maternal organ function, and the effect of bed rest on blood pressure before the optimal timing of delivery is decided.59

Fulminant or severe preeclampsia, with marked blood pressure elevation (160/110 mm Hg) associated with epigastric or liver tenderness, visual disturbance, or severe headache, is managed in the same way as eclampsia (Box 178-4). The goal is prevention of seizures and permanent damage to maternal organs. Magnesium sulfate is given for seizure prophylaxis.

Seizures and coma are the hallmarks of eclampsia, the ultimate consequence of preeclampsia. As in all seizure patients, hypoglycemia, drug overdose, and other causes of seizures should be excluded with appropriate tests. Eclamptic seizures are controlled in almost all patients by adequate doses of magnesium sulfate, although the mechanism of action remains elusive. Magnesium has little antihypertensive effect but is the most effective anticonvulsant, preventing recurrent seizures while maintaining uterine and fetal blood flow. The goals of magnesium sulfate therapy are to terminate ongoing seizures and to prevent further seizures. An intravenous loading dose of 6 g magnesium, followed by 2 g/hr intravenously, is recommended. Magnesium administration should be accompanied by clinical observation for loss of reflexes (which occurs at approximately 10 mg/dL) or respiratory depression (which occurs at levels of 12 mg/dL, although actual serum magnesium levels are rarely monitored). The infusion should be stopped if signs of hypermagnesemia are seen; such patients may require assisted ventilation. Calcium gluconate, 1 g given slowly into a secure vein, will reverse the adverse effects of hypermagnesemia.60

Despite ongoing controversy, the familiarity with magnesium sulfate and its physiologic advantages to the fetus, wide margin of safety, and high success rate in controlling seizures make it the first-line drug in patients with eclampsia. A Cochrane review found that magnesium sulfate is more effective than other anticonvulsants and diazepam for prophylaxis against or treatment of eclamptic seizures, more than halving the risk.69 If seizures persist after the recommended doses of magnesium sulfate have been administered, further therapy should be given in conjunction with obstetric consultation, and a careful search for other causes of seizures (e.g., hypoglycemia and intracranial bleed) should be instituted.

Although magnesium sulfate is not a direct antihypertensive, the hypertension associated with eclampsia is often controlled adequately by stopping of the seizures. Rapid lowering of blood pressure can result in uterine hypoperfusion, so specific antihypertensive treatment is initiated only if the diastolic blood pressure remains above 105 mm Hg after control of seizures. Many patients do not require specific antihypertensive treatment after treatment with magnesium sulfate. The antihypertensive used most often by obstetricians is hydralazine. The dose is 5 mg intravenously, with repeated doses of 5 to 10 mg intravenously every 20 minutes as needed to keep the diastolic blood pressure below 105 mm Hg. Nimodipine and labetalol have also been reported to be safe and effective, although they are less widely used.70 Other antihypertensive agents are not well studied in this population because there are specific risks to uncontrolled lowering of blood pressure and loss of uteroplacental blood flow.

Although total body water in the eclamptic patient is excessive, intravascular volume is contracted and the eclamptic patient is sensitive to further volume changes. Hypovolemia results in decreased uterine perfusion. Thus diuretics and hyperosmotic agents should be avoided in patients with eclampsia. Although intravascular volume expansion in the face of volume contraction, increased systemic resistance, and vasospasm would seem reasonable, invasive monitoring has demonstrated that vasospasm is not reversed with intravenous fluid administration. Rather, excessive intravenous fluids increase extravascular fluid stores that are difficult to mobilize postpartum, resulting in a higher incidence of pulmonary edema in patients treated aggressively with fluid therapy. Invasive pulmonary artery pressure monitoring may be required for accurate fluid management in the eclamptic patient.

Amniotic Fluid Embolus

Amniotic fluid embolus is the release of amniotic fluid into the maternal circulation during intense uterine contractions or uterine manipulation or at areas of placental separation from the uterine decidua basalis (abruptio placentae), triggering a rapidly fatal anaphylactoid-type maternal response. Although amniotic fluid embolus most commonly occurs during labor, in which circumstance the maternal mortality rate is 25% or higher, it can also occur after induced abortions and miscarriages and spontaneously during the second and third trimesters. Amniotic fluid embolus can also occur after amniocentesis or in association with abruptio placentae after abdominal trauma. Although it is a rare syndrome, amniotic fluid embolus is responsible for 13 to 30% of maternal deaths and is the second leading cause of direct maternal death.71

Clinical Features

Amniotic fluid embolus should be suspected during the second or third trimester of pregnancy, particularly in the setting of uterine manipulation or contraction, when a patient experiences sudden hypotension, hypoxia, and coagulopathy. The embolization of amniotic fluid and the particulate matter suspended in it triggers a profound immunologic response when it enters the maternal circulation. The list of proposed mediators is extensive and includes histamine, endothelin, and leukotrienes.71 In survivors, disseminated intravascular coagulation, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and left ventricular dysfunction develop. An initial seizure is seen in approximately 20% of patients. Bleeding diathesis may be the initial sign in some women, and disseminated intravascular coagulation occurs in approximately 50%.

Diagnostic Strategies

When amniotic fluid embolus is suggested, a complete blood cell count, coagulation studies, arterial blood gas analysis, and chest radiograph should be obtained. Urine output should be monitored after urinary catheter placement. The diagnosis is usually made with certainty only at autopsy, with the finding of fetal hairs, squamous cells, and debris in the maternal circulation. Because squamous epithelial cells can be seen normally in the maternal pulmonary circulation, the typical clinical syndrome is also required for diagnosis.71

Differential Considerations

Catastrophic pulmonary embolus, drug-induced anaphylaxis, and septic shock must be considered in the differential diagnosis. Seizure occurs in patients with eclampsia, but hypertension rather than cardiovascular collapse should be observed in that condition. Coagulopathy may be seen in patients with preeclampsia (HELLP syndrome), abruptio placentae, or other chronic coagulopathies seen in the nonpregnant patient.

Management

Amniotic fluid embolus is uncommon, so treatment is mainly anecdotal and based on animal studies. The most helpful modalities appear to be high-flow oxygen, support of ventilation and oxygenation with intubation, aggressive fluid resuscitation, inotropic cardiovascular support, and anticipation and management of consumptive coagulopathy. Adequate management usually requires invasive hemodynamic monitoring in an intensive care unit.

Rh (Anti-D) Immunization in Pregnancy

Rh immunization occurs when an Rh-negative woman is exposed to Rh-positive fetal blood. Small numbers of fetal cells enter the maternal circulation spontaneously throughout pregnancy, but the maternal immune system is triggered only by significant loads of fetal cells, which can occur during the third trimester and at delivery. Sensitization occurs in up to 15% of Rh-negative women carrying Rh-positive fetuses. To prevent this, anti-D immune globulin (RhoGAM) is routinely administered to Rh-negative mothers (if the father is Rh positive or his status is unknown) at approximately the 28th week of gestation to protect the mother from spontaneous sensitization, which occurs during the third trimester. Transplacental hemorrhage can also occur during uterine manipulation, threatened miscarriage (even without fetal loss), spontaneous miscarriage, surgery for ectopic pregnancy, and amniocentesis, although the risk is not clear. Anti-D immune globulin should be administered when these events occur. A dose of 50 µg can be used if the patient is at less than 12 weeks of gestation, although many pharmacies carry only the 300-µg dose, which can also be given. After 12 weeks, a 300-µg dose should be given. The half-life of immune globulin is 24 days, and it needs to be administered within 72 hours of a sensitization event to prevent antibody development.14

The Kleihauer-Betke test of maternal blood has been used to detect fetal cells in the maternal circulation. Unfortunately, the test is difficult to perform, not immediately available in most emergency laboratories, and only sensitive enough to detect 5 mL of fetal cells in the maternal circulation. Because only 0.1 mL of fetal cells is required to sensitize the mother, routine immune globulin administration has been recommended in situations likely to result in sensitization. Patients with third-trimester bleeding are not at increased risk of sensitization compared with patients with normal pregnancy; RhoGAM should be administered only if the patient did not receive her prophylactic dose at 28 weeks.58 In instances of significant blunt trauma to the uterus, the Kleihauer-Betke test should be ordered to detect the rare large fetal transfusions that may require specific fetal blood therapy or administration of additional immune globulin to the mother. The standard dose (300 µg) is sufficient to prevent maternal immunization for fetal transfusions of up to 15 mL of red blood cells or 30 mL of whole blood.14

Medical and Surgical Problems in the Pregnant Patient

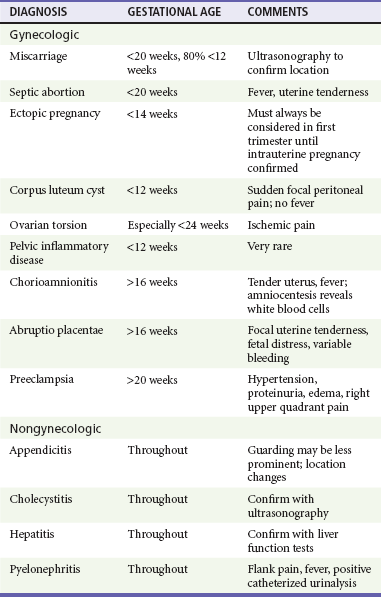

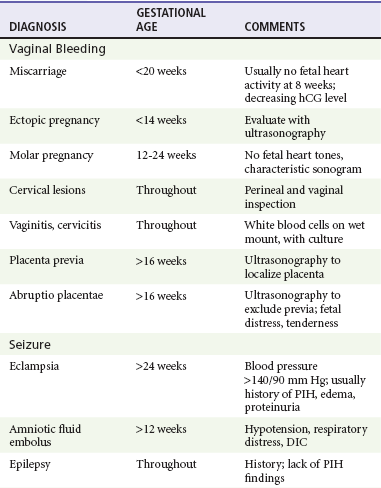

Clinicians should be aware of a variety of illnesses, both related and unrelated to pregnancy, that may have altered symptoms, risk, and treatment in the pregnant patient (Tables 178-2 and 178-3).

Abdominal Pain

Perspective.: Appendicitis is the most common surgical emergency in pregnant patients. The incidence of appendicitis in pregnant patients is the same as that in nonpregnant patients, but delays in diagnosis contribute to an increased rate of perforation, which results in significant fetal mortality and maternal morbidity.72,73 During the first half of pregnancy, diagnostic findings are usually similar to those in the nonpregnant woman, but the clinical picture becomes less classic during the second half of pregnancy.

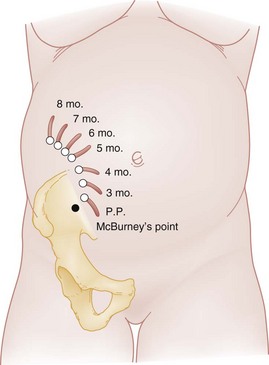

Principles of Disease.: Traditionally, the appendix was thought to be displaced counterclockwise out of the right lower quadrant after the third month of gestation, with its ultimate location deep in the right upper quadrant, superior to the iliac crest (Fig. 178-8). However, one study found that in only 23% of pregnant patients does the location change from the right lower quadrant, even in the third trimester.74 Displacement of the abdominal wall away from the abdominal viscera can result in difficulty in palpation of organs and loss of signs of parietal peritoneal irritation. The physiologic increase in white blood cell count and erythrocyte sedimentation rate in pregnancy should also be considered in the evaluation of the patient with possible appendicitis because these may confuse the overall clinical picture.

Figure 178-8 Locations of the appendix during succeeding months of pregnancy. In planning an operation, it is better to make the abdominal incision over the point of maximal tenderness unless there is great disparity between that point and the theoretic location of the appendix. P.P., postpartum. (From Gabbe SG, et al [eds]: Obstetrics: Normal and Problem Pregnancies. New York, Churchill Livingstone, 2007. Redrawn from Baer JL, Reis RA, Arens RA: Appendicitis in pregnancy. JAMA 98:1359, 1932.)

Clinical Features.: The gastrointestinal symptoms of appendicitis, such as anorexia, nausea, and vomiting, mimic those of pregnancy, particularly during the first trimester, making such symptoms relatively nonspecific. Right-sided abdominal pain is the most constant finding, although this is less reliable later in pregnancy. Peritoneal signs are likewise most common during the first trimester. Lack of fever, leukocytosis, or tachycardia has been reported.74,75 The cause of these differences in clinical findings in pregnant patients with appendicitis may be a blunted inflammatory response from elevated maternal levels of pregnancy-related steroids. Pyuria without bacteriuria is seen in up to 58% of patients.76

Because of confounding factors, the misdiagnosis rate for appendicitis is 30 to 35% overall in pregnancy, with a 40 to 50% rate of removal of normal appendix during the third trimester.74,76 In contrast to the relative safety of performing an exploratory laparotomy or laparoscopy during pregnancy, the risk of fetal loss and maternal morbidity from failure to diagnose appendicitis and perforation is considerable, so clinical vigilance is required even in the absence of classic signs. In later pregnancy, when peritoneal signs are often absent and the uterus obscures normal physical findings, diagnosis is frequently delayed, and the perforation rate may approach 25%.

Differential Considerations.: Pyelonephritis, cholecystitis, nephrolithiasis, and pregnancy-related diseases such as ectopic pregnancy, broad ligament pain, corpus luteum cyst leakage, and ovarian torsion should be considered in the patient who has right-sided abdominal pain. Pyelonephritis is the most common condition that is confused with appendicitis. During its migration, the appendix takes up a position very near the kidney, resulting in a high incidence of pyuria and flank pain (see Fig. 178-8). In cases of appendicitis, unless there is coincident urinary tract infection, the urine is free of bacteria, a feature distinguishing it from pyelonephritis. Salpingitis, another common misdiagnosis, is very rare in pregnancy, although it can occur before 12 weeks of gestation.

Diagnostic Strategies.: Leukocytosis is common in pregnant patients with appendicitis, although it is rarely high enough to distinguish it from the physiologic leukocytosis of pregnancy. Pyuria in a catheterized urine specimen suggests pyelonephritis, but it is also seen in 20% of patients with appendicitis.74 Bacteriuria is uncommon. Ultrasonography, with graded-compression techniques, may reveal a noncompressible tubular structure in the right lower quadrant consistent with appendicitis. Studies regarding the diagnostic utility of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of appendicitis are limited but suggest that it has a high positive predictive value but a low negative predictive value.76,77 Butala and colleagues recommend abdominal ultrasonography as the first imaging modality for patients, and if it is inconclusive, CT is the next imaging modality.78 When it is available, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is also useful in evaluation of pregnant patients with suspected appendicitis (see Chapter 93). Otherwise, laparoscopy or laparotomy is the diagnostic procedure of choice in the pregnant patient thought to have appendicitis. Early exploration is to be encouraged even more in pregnant than in nonpregnant patients because of the variability of clinical signs and the increased fetal risk if diagnosis is delayed.

Management.: The pregnant patient with suspected appendicitis should be admitted to the hospital after appropriate consultation with surgeons and obstetricians. Ultrasonography, MRI, or CT scan should be considered diagnostic options. The patient should be kept on nothing by mouth (NPO) status, with intravenous fluid hydration to maintain intravascular volume. Although prompt surgery is required if the diagnosis is clear, in unclear cases a period of inpatient observation may allow clarification of signs and symptoms.

Gallbladder Disease

Perspective.: Cholelithiasis is present in approximately 5% of pregnant women and is the second most common nonobstetric surgical condition in pregnant patients. The natural history of asymptomatic cholelithiasis is believed to be similar to that in nonpregnant women, with less than half of patients with gallstones developing symptoms.79

Principles of Disease.: Changes in gallbladder kinetics are believed to be due to high pregnancy-related steroid levels. Progesterone decreases smooth muscle tone and induces gallbladder hypomotility and cholestasis, causing an increased risk of stone formation. In addition, pregnancy induces changes in bile composition and increased cholesterol secretion, thus increasing the incidence of cholesterol stone formation.80

Clinical Features.: The signs and symptoms of acute cholecystitis during pregnancy are the same as those in nonpregnant women. Epigastric or right upper quadrant pain and tenderness and nausea predominate. Leukocytosis must be interpreted carefully because of the increased white blood cell count seen normally in pregnancy. Likewise, a slightly elevated amylase level can be normal during pregnancy, and alkaline phosphatase, which is produced by the placenta, may be twice the nonpregnant level. A history of self-limited pain episodes associated with food intake is useful in suggesting the diagnosis.

Diagnostic Strategies.: Ultrasonography is a reliable means of recognizing stones within the gallbladder, although it may not differentiate symptomatic from asymptomatic stones. In the patient with right upper quadrant pain, simultaneous sonographic evaluation of the liver is useful but technically difficult, particularly during the third trimester, when subcapsular liver hematomas and other intrinsic hepatocellular disease can occur but the liver may be obscured under the ribs.

Differential Considerations.: Pyelonephritis should be considered in the patient with right upper quadrant pain with or without fever. During the third trimester, appendicitis can also be associated with right upper quadrant pain. Hepatitis and fatty liver infiltration occur in pregnancy; liver distention and inflammation associated with pregnancy-induced hypertension can also cause right upper quadrant pain. In addition, spontaneous intrahepatic bleeding can occur in late pregnancy, mimicking cholecystitis. Because of the potential for other serious diseases, diagnostic studies should always be performed to verify a clinical diagnosis of symptomatic cholelithiasis and cholecystitis in pregnancy.

Management.: The patient who has fever, leukocytosis, prolonged pain, or evidence of cholecystitis should be made NPO and given intravenous fluid hydration, adequate pain control, and broad-spectrum antibiotics. These patients must be admitted for inpatient management. Some patients can be managed medically for prolonged or complicated cholecystitis. Patients with obstructive jaundice, gallstone pancreatitis, or sepsis or patients who fail to respond to conservative management should have surgery. Discharge should be considered only in patients with uncomplicated and sonographically proven cholelithiasis who do not meet admission criteria after consultation with an obstetrician. Pregnant patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis have a high rate of symptomatic relapse and increased severity of disease with each relapse.81 Early follow-up should be arranged and the patient should be given careful instructions to return if she experiences fever, vomiting, or persistent pain. In one study, patients who were observed during pregnancy had a higher rate of pregnancy-related complications (36%) in contrast to much lower rates of complications in those who had laparoscopic cholecystectomy.82

Liver Disorders

Perspective.: Pregnancy is associated with several unique liver abnormalities in addition to more usual hepatic diseases. Clinicians should recognize the various symptoms of liver disease during pregnancy as well as the hepatic diseases unique to pregnant women. Liver metabolism increases during pregnancy, but hepatic blood flow is unchanged, and little change occurs in liver function. Bilirubin, transaminase, and lactate dehydrogenase levels and prothrombin times are unchanged from the nonpregnant state. Albumin levels decrease secondary to an increase in maternal circulating plasma volume. Alkaline phosphatase levels may be up to double the nonpregnant values, and amylase levels may also be slightly elevated.83,84