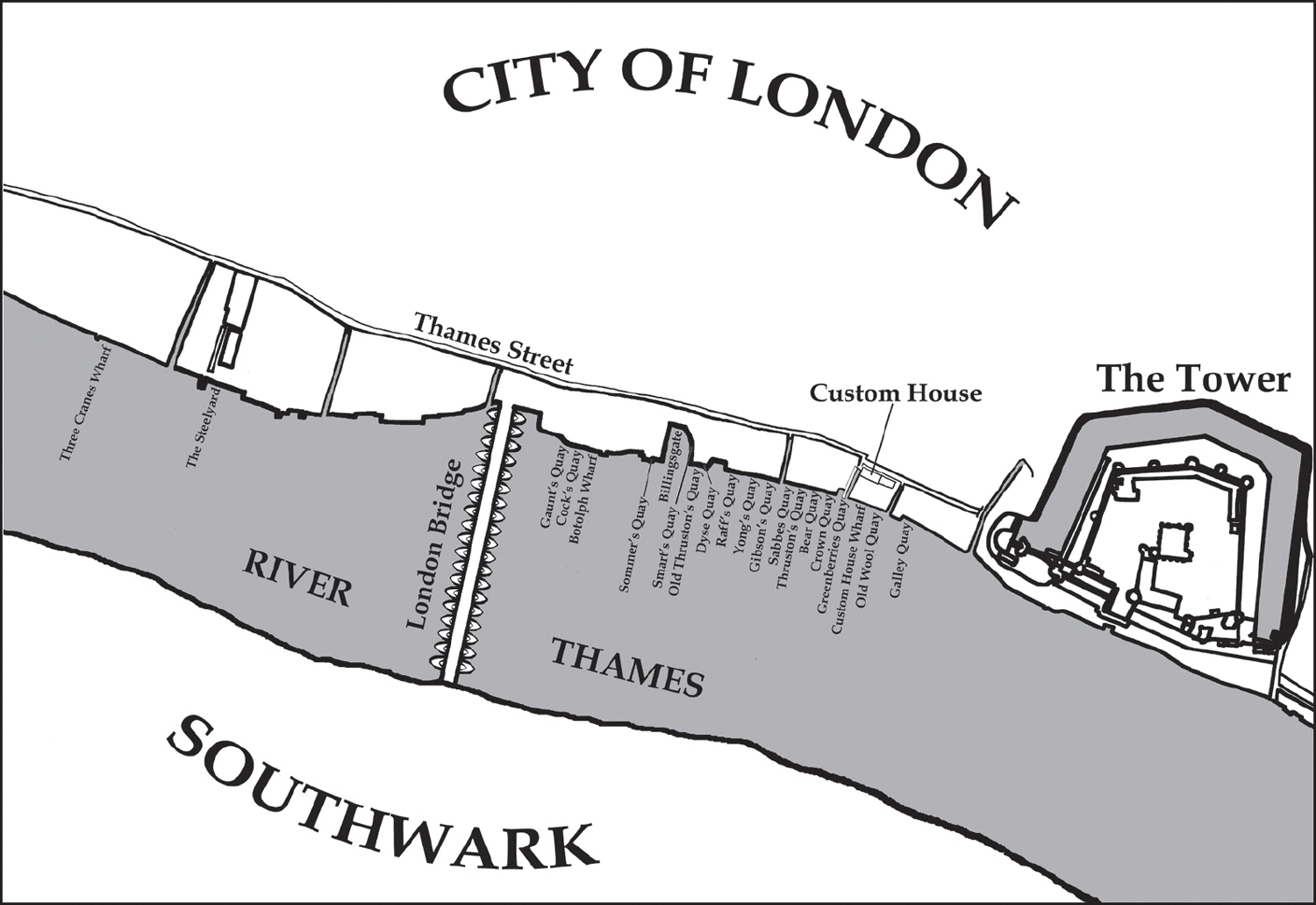

The Legal Quays, as listed in a survey of 1584. Of those originally registered, Bussher’s Wharf and Thomas Johnson’s Quay, each located between the bridge and the Steelyard, were no longer mentioned after 1559.

Throughout the Middle Ages the world’s greatest volume of trade took place in Asia and the Mediterranean. England, in comparison, was a small island on the periphery of Continental Europe. In the early period, foreign merchants came to buy wool and to sell their wine and luxury goods. The export of wool by English merchants was supplanted by that of cloth. England thus began to evolve from being simply a supplier of raw material into an industrialized nation. The value of cloth was far greater than that of raw wool and this brought increased wealth to the country.

During the mid-fifteenth century the English merchant fleet had been in decline and much of the import and export trade was carried on foreign ships, putting the country at a disadvantage. Henry VII understood the importance of international commerce and how it would increase the nation’s wealth. ‘Henry kept out of war, both on the Continent and in his own country. He set himself to make the land of England more productive and the foreign trade more extensive,’ wrote Sir Joseph Broodbank in his History of the Port of London. In the 1480s Henry resolved to increase the fleet by introducing Navigation Acts stipulating that goods should be carried on English ships with English crews. His son, Henry VIII, was rather indifferent to commerce, instead concentrating on strengthening his naval forces, which at least brought shipbuilding to the Thames. It was events that took place during the reign of his daughter, Elizabeth I, that set the scene for England to become one of the world’s financial and commercial superpowers.

By 1500 about 45 per cent of the country’s wool and 70 per cent of cloth exports were passing through London, much of it to Antwerp and England’s outpost at Calais. Yet the economy of the country was still heavily dependent on those products and on exports to nearby countries, stimulated by successive debasement of the coinage. By mid-century the Continental market was saturated, England lost its outposts at Calais in 1558 during the reign of Queen Mary, and Antwerp was closed as a market during a period of religious conflict and never fully recovered. Revaluation of the coinage in the 1560s depressed exports; England needed new markets and more diverse products to stimulate its economy and began to look further afield.

Pepper from the Far East had long been an essential ingredient for cooking and Western Europe was at the far end of a long supply chain that passed through the Islamic world and middlemen such as the Venetians. The vulnerability of this state of affairs was highlighted when supply was cut off following the Ottoman capture of Constantinople in 1453. The Portuguese went around Africa, successfully discovering a new route of their own. In the meantime, the Spanish headed west across the Atlantic looking for new supplies but instead discovered South America and silver. Thus the Spanish were able to pay in silver for spices, brought to Europe by the Portuguese who violently enforced their monopoly on the trade. For a century the spice trade between Asia and Europe was dominated by the state-owned Portuguese Estado do India from their base at Goa.

Throughout the sixteenth century much of Northern Europe turned towards Protestant beliefs and the Netherlands revolted against their Spanish Catholic rulers. The newly-independent Dutch created a strong navy to defend themselves but they also used it to plunder Spanish and Portuguese maritime trade and established their own spice trade with Asia. Protestant England became reliant on the Dutch for their pepper but in 1599, when the price tripled, English merchants resolved to create their own spice route to the Far East.

The Thames, and in particular its estuary and approaches, holds numerous dangers for navigation. Many vessels have run aground over the centuries, particularly in the days of sail, before reliable charts, when ships tended to stay within sight of the shore in order to navigate by landmarks such as church spires. The Maplin Sands and many other long, shifting, tongues of sand lie up to forty miles off the Essex coast where the Thames meets the North Sea, to be avoided by ships passing into and out of the estuary on the way to east coast ports and beyond. Some are in a Y-shape, where an apparently deep channel ends in a fatal cul-de-sac. Ships en route from London and east coast ports down to France and southern Europe must pass the Goodwin Sands off the Kent coast, described by Shakespeare in The Merchant of Venice as ‘where the carcasses of many a tall ship lie buried’. Well over a thousand vessels have been recorded as having been lost there since the late fifteenth century, and parts of unrecorded, more ancient, vessels still occasionally snag the nets of fishing boats.

It was vitally important for mariners to understand the underwater dangers, the ever-changing times of the tides according to the moon and location along the river, the effect of the wind, and to know local landmarks in poor visibility. During the thirteenth century the monks of St Albans had compiled tables of the high tides at London Bridge. Local experts, known as ‘lodemen’ in the Middle Ages, could be hired to advise on the best channels along which to navigate. The term dates back to at least the 1380s and is referenced in the Shipman’s Tale of the Canterbury Tales. Chaucer wrote:

His stremes, and his daungers hym bisides, His herberwe, and his moone, his lodemenage

(His current and the dangerous watersides, His harbours, and his moon, his pilotage)

The ancient nautical medieval Law of Oleron stated that if a ship was lost by default of the lodeman it was a mariner’s right to have him executed by cutting off his head, providing it was the majority decision of the crew.

In 1513 a group of eminent masters and mariners petitioned Henry VIII that the standard of pilotage on the river had declined in recent times and regulation of pilots was required. The King may or may not have had an interest in the safety of merchant ships but Henry was at that time at war with France. The mariners pointed out that the scarcity of English pilots caused Scots, Flemings and Frenchmen to learn the secrets of the river, thus jeopardizing English security. From its foundation by letters patent in May 1514 responsibility for safety on the river was given to ‘The Master, Wardens and Assistants of the Guild or Fraternitie of the most glorious and blessed Trinitie and Saint Clement in the parish Church of Deptford Stronde in the County of Kent’, otherwise known as Trinity House, Deptford. The organization was to provide pilotage – the safe guiding of ships by experienced English pilots – along the Thames, particularly through its shifting sandbanks in the estuary.

The membership of Trinity House consisted of those with various nautical interests and over time they gradually became involved in a range of maritime safety measures. They were distinct from the Fellowship of Lodemanage of the Cinque Ports, based at Dover and formally incorporated in 1527, which was concerned solely with pilotage. The two organizations between them provided authorized pilots for ships navigating the Thames. After the Fellowship was discontinued in 1854 Trinity House took over complete control of pilotage on the Thames.

An Act of Parliament of 1566 under Queen Elizabeth extended the responsibility of Trinity House to ensure the upkeep and continuation of seamarks around the coast, those being landmarks such as church steeples and trees used by mariners to fix their position. In 1594 the provision of beacons and buoys was similarly transferred from the Lord High Admiral, and the Corporation gradually began providing lighthouses, their first probably being at Lowestoft in the early years of the seventeenth century. The cost to the Corporation regarding all these works was funded by dues paid by ships arriving at London, where they were collected by the officials of Custom House, and at other ports.

The 1594 Act also transferred the right to provide ballast to ships on the Thames, which was particularly necessary for colliers returning empty to Newcastle. Using wet ballast also reduced the cost of the important dredging of the Thames to prevent silting. The Corporation’s rights and responsibilities were further extended in 1604 under James I, including the supervision of apprenticeships of seamen, and to hold a court dealing with disputes, such as those between masters and seamen or regarding damage to ships.

Trinity House was governed by a court of eighteen Elder Brethren, some of whom were leading mariners, navigators and naval men of their day, who met at least once each week. At some point in its early years a lower class of Younger Brethren came into being, numbering 254 by 1629, mostly living around Stepney or Rotherhithe. The expansion of the membership effectively created a guild consisting largely of shipmasters, limited to natural-born Englishmen who could afford the subscription. The Brethren were headed by a Master, the first of whom was Thomas Spert, an experienced and eminent seaman from Stepney who rose through the ranks to captain the great Henri Grace à Dieu. He was knighted in 1529 and held the post until his death in 1541.

After Spert, a new Master was elected at Trinity House every three years and the naval administrator and diarist Samuel Pepys held the position of Master on two occasions. It gradually became an honorary role, held by the Duke of Wellington between 1837 and 1852, with the management undertaken by the Deputy Master. Since 1866 it has been bestowed on a member of the royal family. For forty-two years it was held by the Duke of Edinburgh until his retirement in 2011 when it was conferred on the Princess Royal. Elder brethren have included Winston Churchill.

In order to achieve their aims, it was necessary for the Elder Brethren to be both supporters of, and have the support of, the monarchs. During the Interregnum in the mid-seventeenth century the powers of Trinity House were transferred to a Parliamentary Committee, although they continued as advisors. At the Restoration in 1660 the responsibilities of Trinity House were reinstated.

In 1618 the working headquarters of Trinity House moved to Ratcliff, the area where many of London’s merchant seaman resided. Following the Restoration a move was made to Water Lane, close to the Tower of London. That building was destroyed in the Great Fire, as was its successor in 1714. After extensive repairs in the 1790s the headquarters moved for the final time into a grand building facing the Tower of London across Tower Hill, designed by the architect Samuel Wyatt and completed in 1796. It was largely destroyed during an air raid in December 1940 but restored with much Georgian detail in 1953 and is Grade 1 listed. Many of the historical records and artworks were destroyed in the fires and bombing although some records from as early as the seventeenth century are still in existence. The building now contains a magnificent collection connected to its history, including a contemporary portrait of Elizabeth I.

From the beginning, Trinity House was involved in charitable work. Almshouses for elderly seamen and their widows were created at Deptford. In 1695 Captain Henry Mudd, an Elder Brother, provided an estate of houses and a chapel on his land at Whitechapel north of Ratcliff. Much of it still remains at Mile End Road although no longer for its original purpose. Pensions were also paid to elderly or injured seamen, and by 1618 they were providing for 160 people, which had risen to over 1,100 in 1681.

As part of its responsibility for buoys and lighthouses, at the beginning of the nineteenth century Trinity House established riverside workshops near Blackwall, where the River Lea joins the Thames. From there maintenance work could be carried out and experiments undertaken, for which two lighthouses were built at the yard. The electrical scientist Michael Faraday was appointed Scientific Advisor in 1836 and undertook experiments that led to advancements in lighthouses around the coast. Trinity Buoy Wharf continued in operation until 1988 and the main buildings and one lighthouse still exist.

Trinity House continued as the sole authority for pilotage on the Thames and around the coast until 1986, by which time it managed around 500 self-employed pilots. At that time responsibility for pilotage on the river was transferred to the Port of London Authority. Trinity House today works as a licensed authority for deep sea pilotage in Northern European waters, as well as for navigation aids, including lighthouses, lightships and buoys, around England, Wales, the Channel Islands and Gibraltar. It continues to carry out charitable as well as educational work including a cadet training scheme. In modern times the Elder Brethren are supported by around 300 Younger Brethren.

Ships had over the centuries been gradually increasing in size and by the early fifteenth century the largest were 1,000 tons. The general trend for larger ships thereafter reversed and the size of seagoing cargo vessels became smaller throughout Europe, with the majority between 100 and 150 tons and rarely exceeding 200 tons. Advantages of smaller ships are that they require less crew, can enter smaller harbours, are quicker to load and unload, and their loss easier to bear if sunk. The English merchant navy remained modest by European standards at the beginning of Elizabeth’s reign, with only 250 vessels above eighty tons. Navigational aids remained rudimentary, forcing crews to stay within sight of land as much as possible.

At the end of the fifteenth century new methods of ship construction were introduced in England and around Europe. Until then wooden ships had been made in the ‘clinker’ style where each plank of the hull overlapped the one below, with the shell constructed first and the frames added later. From at least 1465 the new ‘carvel’ method began to be used, where each plank butts edge-to-edge with the next. Construction began with the skeleton to which the planks were fastened. The new method made the vessel much stronger and allowed for gun-ports in naval ships, such as the Mary Rose, launched in 1511. The type of timber changed from oak to elm in the sixteenth century, sawn instead of split. With larger ships also came the introduction of more sails, with more than one mast to support them. These new ships were more robust, more easily manoeuvrable, of larger capacity, faster and cheaper to build.

The changes, and local shipbuilding, were stimulated in England by the creation by Henry VII of the first permanent navy. When Henry VIII was at war with France he found it inconvenient that the navy was based at Portsmouth, far from his palaces and the Royal Armoury at the Tower of London. He decided that the ideal locations were close to his palace at Greenwich, at the Kent fishing villages of Deptford, Woolwich and Erith, which were not only more convenient but also easier to defend than Portsmouth. Initially there was a lack of skilled workmen and they had to be conscripted from as far as Newcastle and Cornwall. Over time however, these yards enlisted men with shipbuilding and repairing skills and there was a need for local suppliers and administrators with suitable knowledge. All these factors eventually created an industry that was not only useful for merchant shipping but for the wider Port of London. Initially the facilities on the Thames were rather small but during his reign Henry invested heavily in the navy and they expanded and became betterorganized. The King’s Yard at Deptford expanded to thirty acres, including two wet-docks, three slips large enough for warships, and with forges, ropemaking and other facilities. The area to the east of London grew to become the shipbuilding capital of England by the end of the sixteenth century.

The ‘great gun’, a cannon that could fire over a long range, revolutionized naval warfare, with warships able to engage enemies from a distance.. The Mary Rose was constructed at Portsmouth but fitted out on the Thames in 1512 with bronze cannons made in a London foundry. A state-of-the-art warship, it became the flagship of Henry’s navy, perhaps the first to carry the great gun, and served in his navy for over thirty years. In 1513 Henry commissioned what was at that time the largest English ship afloat, the Henri Grace-á-Dieu (Henry, Thanks be to God) but popularly known as the Great Harry. It was built at Woolwich, downriver of Greenwich, which had the advantage of a ready supply of wood from the forests of Kent to build new ships.

During the Middle Ages most of the merchant ships sailing from London were built in Holland or Flanders but the growth of Henry’s shipyards brought many of the necessary skills to the River Thames. Therefore a local shipbuilding and repair industry grew at yards downstream of London at the riverside hamlets of Wapping, Shadwell, Blackwall and Rotherhithe. Few, however, were permanent yards employing permanent staff; more often vessels were built on available land by transient shipwrights.

Despite progress, shipbuilding on the Thames and elsewhere throughout England would continue to be rather small-scale until the advent of longdistance trade, with most vessels less than 100 tons. During the Dutch wars of the mid- to late-seventeenth century around 2,000 merchant ships on either side were captured. The Dutch were the leaders in merchant ship design, building ‘fluits’ (known as ‘flyboats’ in English) that moved under less sail. They required a smaller crew, and were more space-efficient and thus carried a greater cargo. English merchants preferred to use captured Dutch ships rather than locally-built vessels and shipbuilding yards in England received fewer orders during the latter part of the century. In response the English yards began to copy the Dutch designs and as the captured ships came to the end of their working lives business once again picked up in the English yards. There was also new competition from shipyards in the American colonies, which under the Navigation Acts qualified as English until Independence, where there was the advantage of abundant supplies of timber. In the 1770s around a third of all British ships had been built in America but American Independence once again gave British shipyards a boost in business. Even though many of the ships on the river during the eighteenth century had been built elsewhere, shiprepairing continued to be a thriving business.

In 1552, during the reign of Edward VI, the Commission on the King’s Courts of Revenue issued a report and, as a result, customs duties were increased and many more commodities added on which duty was payable. This made the collection of duties more complex and smuggling more profitable. Therefore a reform of ports was initiated by the Lord Chancellor, William Paulet, Marquis of Winchester. An Act of Parliament was passed in 1559 establishing general regulations for loading and unloading and a commission was appointed to survey the ports. The outcome was that, with the exception of fish, goods could henceforth only be unloaded during daylight and only at certain quays at London, Southampton, Bristol, Newcastle and certain other ports where customs officials were present. In London, arrivals of overseas goods were to be limited to particular wharves along the riverbank in the City and these became known as ‘Legal Quays’. Incoming vessels were forbidden to touch land after passing Gravesend. Those wharves at the ancient Queenhithe – in use since Saxon times – as well as Gravesend, Barking, Blackwall and many other places, ceased to be used for goods on which duty was payable.

The Legal Quays, which lined the southern side of Thames Street, were to maintain their monopoly on the landing of foreign imports into the Port of London for the following 250 years. Their names changed over time, often according to their ownership. A survey of 1584 listed them as:

| Three Cranes Wharf | The largest of the Legal Quays and located at Vintry, it was used for landing wine and ‘waynscotts’. |

| The Steelyard | For the exclusive use by the German Hanse. By the time of the survey a crane was in use. |

| Fresh Wharf | For eels and fish. |

| Gaunt’s Quay | A very small wharf where barrels of fish were landed. |

| Cock’s Quay | For foreign merchants, including lodgings. |

| Botolph’s Wharf | Used by the Russia Company as well as coastal traffic. |

| Sommer’s Quay | Located on the west side of Billingsgate and owned by the City, it was used exclusively by Flemish merchants. |

| Billingsgate and Smart’s | Both forming the Billingsgate harbour and owned by the City. |

| Quays | Fish, vegetables, fruit and grain were landed. Smart’s Quay was on the east side of Billingsgate. |

| Old Thurston’s Quay | For coastal trade and Flemish goods. |

| Dyse Quay | An open and unprotected quay used for coastal trade. |

| Raff’s Quay | For imports and exports of general merchandise. |

| Young’s Quay | Where Portuguese cloth was landed. |

| Gibson’s Quay | For lead, tin, and other coastal trades. |

| Sabbe’s Quay | Cargoes of pitch, tar, ‘soap ashes’ and other goods were landed. |

| The property was generally in a poor state at the time of the survey. | |

| Thurstan’s Quay | For imports and exports of general merchandise. It no longer existed by the time of the Great Fire, presumably amalgamated with its neighbours. |

| Bear Quay | Used by merchants from Portugal who lived there, as well as coastal trades. |

| Crown Quay | For coastal trade in wood and corn. |

| Greenberry’s Quay | Used for imports and exports from France and coastal trade. |

| Custom House Quay | Purchased by the Crown in 1558 and leased out, it was used for |

| (or New Wool Quay) | general imports and exports such as fine wares and haberdashery. It later returned to private ownership. |

| Old Wool Quay | This was one of the oldest quays on the riverside, dating back to the thirteenth century or earlier and named after the wool ships that loaded there in previous times. It had been purchased (from the Coopers’ Company) by the Crown two years before they acquired Custom House Quay. At the time of the survey it was used for landing wood and by coastal trades. |

| Galley Quay | Formerly a place for shipbuilding but by then for unloading general merchandise. |

The Legal Quays, as listed in a survey of 1584. Of those originally registered, Bussher’s Wharf and Thomas Johnson’s Quay, each located between the bridge and the Steelyard, were no longer mentioned after 1559.

In some cases the Legal Quays were separated from each other by small wharves that were unregistered and therefore presumably only handled goods on which duty was not payable. Bridgehouse at Southwark was the only authorized landing place on the south bank. It was there that grain was unloaded for storage in granaries and for baking.

After creating the Legal Quays, Winchester turned his attention to improving customs administration throughout the country, detailed in his Book of Orders, issued in 1564. These set out the hierarchy of responsible officials within the Port. The Exchequer would henceforth issue port books – special parchment books – to the senior collectors in which details of ships, their cargoes and revenues were to be entered. The system included two separate controls in order to reduce the possibility of fraud. All goods were to arrive at the wharves by lighter (a barge for moving cargoes to and from ships), except in cases of those that were so large they had to be unloaded by crane. By the 1560s mechanical cranes were being used at Three Cranes Wharf, each operated by a man inside a cabin in the crane’s structure.

An Act of Parliament of 1663 provided the width of river frontage of all the City quays, varying from the widest – Custom House Quay at 202 feet – to the narrowest – Hammond’s Quay (between Botolph’s and Cock’s Quays) at just 23 feet. Three years later the Tudor-era wharves and warehouses from the Tower to Temple church were swept away during the Great Fire but by then some people had anyway thought the rotting timber wharves, the disorganized mass of warehouses and narrow lanes, were due for renewal. Visionaries including Sir Christopher Wren proposed a new broad quay running the entire length of the City, details of which were included in the second Rebuilding Act in 1670. Plans were drawn up by Robert Hooke but disputes with wharfingers regarding compensation delayed the project, which was only properly implemented along the Thames end of the River Fleet, Blackfriars, Dowgate and Puddle Dock. In the event, most individual wharfingers, notably those owning the Legal Quays below the bridge, rebuilt as they saw fit.

The need to find new markets became critical in the second half of the sixteenth century when the lucrative Antwerp trade collapsed, although exploration for new lands and routes had already begun in the previous century. The Spanish and Portuguese initially dominated the transatlantic trade routes. The earliest voyages westwards from England were undertaken from Bristol where John Jay the younger made an unsuccessful attempt to find the ‘Island of Brazil’ in 1480. Englishmen managed to reach Newfoundland and, later, continental North America under the Italian Giovanni Caboto (John Cabot) in 1497, partly supported by merchants from London. Giovanni’s son, Sebastiano, made several voyages to North America in English ships, including unsuccessful attempts to discover a north-west passage to the Far East.

In May 1553 Sir Hugh Willoughby and Richard Chancellor set off from the Thames in three ships with the aim of finding an alternative north-east passage to the Orient without interference from the Portuguese who controlled the route to the Far East around Africa. Whereas Portuguese exploration and trade was state-led, that of the English was to be almost entirely private-enterprise. To fund the voyage, London merchants purchased shares in the joint-stock ‘Mystery and Company of Merchant Adventurers for the Discovery of Regions, Dominions and Islands and Places Unknown’. Two of the ships became trapped in Arctic ice and Willoughby and his crew perished but Chancellor reached the harbour of Nikolo-Korelsky from where he was invited to Moscow by Tsar Ivan IV (Ivan the Terrible). They made an agreement that took English cloth to Russia in return for Russian furs, timber, tar and other commodities. In 1555 Chancellor returned to London and a charter was granted to the Russia (or Muscovy) Company by Queen Mary and her husband King Philip of Spain. In 1558 representatives were able to travel by way of Moscow to reach the great Persian market of Boghar, where goods from China and India could be traded. Queen Elizabeth confirmed a new charter in 1566 and in the following years the Company was granted a monopoly by the Tsar on goods passing beyond Moscow to Persia. The Russia Company was the first English long-distance joint-stock company and its influence on the future of London as a trade centre was enormous. In 1557 Chancellor’s successor at the Muscovy Company, Anthony Jenkinson, opened a new route through Russia to Central Asia, diverting trade from the old Silk Route. In 1613 the Company was granted a patent by James I giving them a monopoly on whaling off the coast of Greenland, although they had strong competition from the Dutch. The Muscovy Company continued trading with Russia, importing iron, tar and copper as well as fur, and survived until the Russian Revolution in 1917. It continues today as a charity. The Company sponsored the explorer Henry Hudson to seek a north-west passage to the Orient. Although unsuccessful in that quest he did make discoveries in the North-East of America, including what was named Hudson Bay.

Other English chartered companies were formed in the sixteenth century either as groups of merchants similar to the Merchant Adventurers or as jointstock companies, each granted a monopoly on trade within a certain area of the world. The Eastland Company was formed in 1579 to trade around the Baltic, overlapping with areas monopolized by the Merchant Adventurers, and competing directly with the Hanse. There were several attempts by London merchants to create a Spanish Company to regulate English trade with the Iberian Peninsula. They ultimately failed due to either war or opposition from provincial merchants who were very active in trade with the near-Continent.

A group of English merchants were keen to establish direct business with the Ottoman Empire in order to avoid the high price of oriental goods passing through Venice and Antwerp. The Grand Dukes of Tuscany opened the port of Livorno in north-western Italy to foreign merchants and an English base was established there in 1573. Five years later a treaty of reciprocal safe conduct was agreed between the Sultan in Turkey and Queen Elizabeth at a time of mutual opposition to Spain. Elizabeth issued letters patent and the first English ship arrived at Constantinople in June 1584. Cloth was sent and spices, silks, dyes, grapes, currants and other merchandise brought back. In 1592 a charter was issued to the Levant Company, amalgamating the former Turkey and Venice Companies, with a monopoly on trade for its members from Venice to the ‘newly discovered’ East Indies. A flourishing trade developed thereafter, particularly in currants, as well as cotton and other exotic merchandise. London became a major base of trade with the Mediterranean, exporting cloth, tin, lead and fish and importing wine, cotton, dried fruit and other luxury goods. The Levant Company continued until the early decades of the nineteenth century. Many of the same merchants who comprised the Levant Company were also members of the Barbary Company, which was formed in 1585 and primarily imported sugar from along the Atlantic coast of Morocco.

The Guinea Company initially dealt in redwood from around Sierra Leone and became a joint-stock company in 1618. It turned its attention to the search for gold with limited success and its interests in Africa were taken over by the East India Company in 1657. In the 1640s sugar plantations were established on Barbados creating a demand for slave workers. The Company of Royal Adventurers into Africa was formed in 1660 by the Duke of York (later King James II) and Prince Rupert, establishing a fort in Gambia. Its main business was in gold, which it minted into coins, but it soon found slavery to be a lucrative additional business. Its intrusion into Dutch trading territory led to the Second Anglo-Dutch War and the company ceased to trade from 1665. It was succeeded by the Royal African Company, dominated by merchants, primarily supplying slaves to Virginia and the West Indies. Its monopoly on slave-trading ended in 1698 when that was opened up to other British companies.

Unsuccessful attempts were made to establish English colonies in North America in the 1580s. The first was founded by Sir Humphrey Gilbert at St John’s in Newfoundland in 1583 but it collapsed due to disease and Gilbert drowned on the return voyage. Two years later Gilbert’s half-brother, Walter Raleigh, attempted to create a colony further south at Roanoke, off the coast of what is now North Carolina. The war between England and Spain prevented supplies from reaching the colony between 1588 and 1589 and English ships arriving in 1590 found it deserted. Despite the setbacks during her reign, the area along the eastern seaboard, from what is now South Carolina and north to Maine, was nevertheless named ‘Virginia’ after the Queen.

In 1606 King James issued royal charters that established the Virginia Company of London and the Plymouth Company, both joint stock companies whose shares were traded in London. Their aim was to establish permanent colonies in North America and they were each granted rights to certain areas in which they were able to create settlements. The following year three London Company ships set sail from Blackwall to establish Jamestown on the James River in Chesapeake Bay, the first successful permanent British colony in North America. When the Plymouth Company’s Popham colony failed, its territory was handed to the Virginia Company. A later charter gave the Company additional ocean territory including the island of Virgineola (Bermuda). It became ever more obvious that the London Company could not meet its obligations and King James changed the status of Virginia to that of a direct colony of the Crown in 1627, as it remained until the American War of Independence in 1776. New colonies were also established in New England, Massachusetts and Maryland. Virginia and the Bermuda Islands exported tobacco; new colonies at Barbados, St Christopher, Nevis and Antigua found greater success growing sugar. The initial impact of the colonies in North America was small but during the first half of the seventeenth century, particularly once the slave business was established, their importance to Britain’s trade became significant. In 1660, shortly after regaining the throne, Charles II signed an Act stipulating that all goods imported from the colonial plantations should be carried in English ships.

Yet another unsuccessful attempt to find a north-west passage to the Far East was made on English ships in 1668 by the French traders Pierre-Esprit Radisson and Médard Chouart des Groseilliers. They nevertheless brought back to London beaver furs from north-east America and gained backing from Prince Rupert. Charles II granted a charter that founded the Hudson’s Bay Company with a monopoly in trading in all the lands that have rivers and streams draining into the Hudson’s Bay, which later proved to be a vast area from the Arctic Circle south to Dakota and west to the Rockies. Some of their trading forts, such as Winnipeg and Edmonton, grew into major cities. In a similar way to the East India Company, Hudson’s Bay governed the lands in which it traded until handing them to the British Crown in 1869. The Hudson’s Bay Company is the last of the early London-based Chartered Companies still in operation and the present monarch still retains a shareholding. Its headquarters moved from the City of London to Toronto in 1970. Shopping bags in their stores throughout Canada continue to boast ‘Incorporated 2 May 1670’.

The reign of Queen Elizabeth was dominated by wars with Spain. English vessels were licensed as privateers, to plunder the ships and ports of the enemy. The onset of peace, in 1604, left shipowners with large, well-armed vessels, well-suited for long-distance trade, as well as the reopening of previously closed markets.

Maritime commerce and voyages of discovery required finance but by the sixteenth century Europe’s major money market was at the Antwerp bourse. It was largely through the efforts of Thomas Gresham that a new financial exchange was established in London, laying the foundation for the City to become the world’s foremost commercial centre.

The growth of trade in London, including the funding of voyages of exploration in the sixteenth century, led to an increasing number of merchants and syndicates raising finance within the City. International shipping and trading was a lucrative but risky business and merchants needed to share that risk rather than possibly losing everything by borrowing. Initially they would do business with each other in the streets. Lombard Street, named after Italian financiers from Lombardy who had settled there, was the main centre for this. Other locations used were in and outside St Paul’s or within the halls of the Livery Companies.

Two of London’s leading men of the mid-century were the Gresham brothers, John and Richard. They were hard-working members of the Mercers’ Company who both amassed a fortune and rose to become Mayor of London. John was one of the founders of the Muscovy Company. Richard, who lent money to Henry VIII, was knighted in 1531 and John six years later. Richard proposed a new establishment in Lombard Street where merchants could meet to do business with each other but he died before the plan could be realized.

It would be left to Richard’s second son to accomplish the idea. Thomas was born in Milk Lane in around 1518. At 17 he joined his uncle John’s drapery business, working in both London and the Low Countries. Living between the two, Thomas was able to speak both English and Flemish as well as French and classical languages. He also studied law at Gray’s Inn. While still an apprentice, he came to the attention of Henry VIII’s chief minister, Thomas Cromwell, and began undertaking errands on the Continent for the King. Following his apprenticeship, Thomas gained the right to membership of the Mercers’ Company in 1543. Three years later he took control of the family business in the Netherlands, exporting woollen cloth from England and importing fine cloth and armaments. When English cloth became less competitive at the Continental markets in the 1540s he diversified into metals.

Gresham was appointed as the royal agent during the reign of the young Edward VI, responsible for borrowing at the Antwerp bourse where he was able to play the market in order to successfully reduce Crown loans. His moment of glory was cut short when the young Edward died and was succeeded by his sister Mary. Gresham and his fellow Merchant Adventurers were suddenly out of favour due to their association with the Duke of Northumberland, who had attempted to put Lady Jane Grey on the throne, and he returned to his commercial activities. When Gresham was reinstated as royal agent following Mary’s death he was able to borrow more favourably for Queen Elizabeth and again greatly reduce the Crown’s loans. Now with the full support of the monarch and her chief minister, William Cecil, he became involved in several government services and initiatives. Gresham was knighted in 1559 for his services to the Crown and continued as the royal agent for the first nine years of Elizabeth’s reign.

Tragedy struck in 1564 when Thomas’s son died in a riding accident. Without a male heir, and already in poor health, Thomas decided to use some of his large fortune to create a lasting legacy for the general good, reviving his father’s idea of a public building where businessmen could carry out transactions to rival the bourse of Antwerp. A site was chosen at the junction of Cornhill and Threadneedle Street, and over £3,700 raised by subscription to purchase and demolish thirty-eight houses. The new exchange was completed at the end of 1567. Initially the idea was slow to take off and it took some years before it was fully used. In January 1571 the Queen visited to officially open the building. The market was given a royal charter and thereafter renamed the Royal Exchange.

Antwerp’s golden period as the cultural and financial centre of Europe ended when that city was sacked by the Spanish in 1576. A large part of the population fled following a siege in 1585. Many of the bankers emigrated to London and thus enhanced London as a major European finance centre to supersede its Continental rival. After his death in November 1579 Gresham was buried at St Helen’s Bishopsgate, with a still-extant tomb that may have been shipped from Antwerp. The Gresham family symbol of the grasshopper continues to be used by Gresham College, which he founded as London’s first university-style institution, and on the weather vane of the Royal Exchange.

In the early part of the eighteenth century Joseph Addison was able to write in his Spectator magazine: ‘There is no place in the town which I so much love to frequent as the Royal Exchange. It gives me a secret satisfaction, and, in some measure, gratifies my vanity, as I am an Englishman, to see so rich an assembly of country-men and foreigners consulting together upon the private business of mankind, and making this metropolis a kind of emporium for the whole earth.’ Nearly a hundred years after its foundation, the original Royal Exchange was a victim of the Great Fire. It was subsequently rebuilt on two occasions and its successor of the 1840s, facing the Bank of England and Mansion House, continues today as an upmarket shopping centre.

A significant factor in the immense growth of the Port during seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, as well the increasing business and prosperity of London, was that it was the home of the East India Company. For over 200 years the capital had a monopoly on trade with the Far East.

For centuries Asia was the world’s greatest manufacturing area, with spices and exotic luxury goods sent overland from there to Europe via Istanbul and on to Venice. Thus a camel was incorporated into the heraldic device of London’s medieval Grocers’ Company. Vasco de Gama was the first European to open a direct sea route with the Far East in 1499 and the Portuguese monopolized maritime routes with India and China for the next century. The Dutch reached Bantam in Java from where they returned with spice, leading to the formation of the Verenigde Oostindische Compagnie (VOC) in 1602. It established a dominant position during the following century, particularly under the brutal Jan Coen, founder of Jakarta and the Company’s Governor General from 1619. With a fleet of over 100 ships, the VOC accounted for half the world’s shipping. The Dutch were eventually expelled from India by the British, ceased operations following the Anglo-Dutch War in the 1780s and the Compagnie was declared bankrupt in 1799.

English merchants had made exploratory voyages to the Far East under a royal charter granted by Elizabeth I in 1581, most likely to make raids on other European traders rather than trade in their own right. A group of English ships set out from Plymouth in 1591 under Captain George Raymond but it was a disaster, with all three ships lost. Only a handful of men, under the command of James Lancaster, one of the ships’ captains, arrived back in England, having been rescued by French vessels. Nevertheless, the booty the survivors had amassed, and the information they conveyed, encouraged English merchants in their desire to carry out better-prepared voyages.

At least two expeditions set out from England carrying letters from Queen Elizabeth to the Chinese Emperor requesting trade agreements. Sir Robert Dudley dispatched three ships under Captain Benjamin Wood in 1596 but they never returned. Another expedition the following year was headed by merchants Richard Allen (or Adam) and Thomas Broomfield, although evidence of success is lacking. An early attempt to trade with China in 1637 was blocked by the Portuguese.

When the Dutch first returned from Java laden with pepper in 1599 its price almost tripled in England, which made London merchants determined to create their own monopoly of the trade. A meeting was chaired by the Mayor at Founders’ Hall and an association was formed. On New Year’s Eve 1600 a royal charter was granted to the ‘Company and Merchants trading to the East Indies’, or ‘East India Company’, giving them a monopoly on English trade between the Cape of Good Hope and Magellan’s Strait.

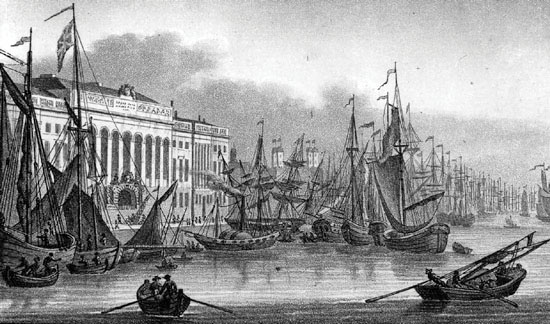

A small fleet of well-armed ships carrying around 500 crew, many of them Thames watermen, sailed from Woolwich, backed by 218 subscribers. The Company was given the right to export silver – something that had previously been illegal – in order to purchase spices. The first voyage was not made until a peace agreement with Spain allowed English ships to safely navigate south. The vessels set sail from Woolwich in February 1601 under the command of James Lancaster, who had survived the doomed expedition of 1591. A variety of goods, including metals, fabrics, lace and gifts for foreign officials, as well as bullion, were sent on the outbound voyage. Despite poor sailing conditions that made for slow progress and many of the crew succumbing to scurvy, they arrived at Achin on the Indonesian island of Sumatra in the spring of 1602. A trade agreement with the Sultan was struck and a small settlement established as a base. Pepper, cloves, indigo, mace and silk were brought back, providing substantial returns for the investors. Continuing voyages ensured that spices were thereafter widely available in Britain, changing the nation’s cuisine.

In 1608 the Company established a transit point at Surat, the main port of Gujarat on the north-west coast of India and another two years later at the town of Machilipatnam in the Bay of Bengal on the east coast. The Company’s ships often clashed with those from the Netherlands and Portugal and in 1612 they won an important victory at the Battle of Swally. In 1613 an agreement was made with the shogan to establish a trading post on Japan’s southern Hirado island (although it closed a decade later when Japan shut itself off from the world). Two years later a diplomatic mission sent on behalf of King James made a commercial treaty with the powerful Mughal emperor, who ruled much of the subcontinent, giving the East India Company exclusive trading rights with the Surat region. By 1640 the English and Dutch had broken the Portuguese monopoly on trade with the Far East.

Each of the early voyages were funded as individual ventures but in 1657 a permanent joint-stock corporation was formed, allowing the shares to be publicly traded. They could initially be purchased from the East India headquarters and later at the Royal Exchange. After a further two years, following a charter to the Company from Oliver Cromwell, an important supply base was established on the island of St Helena in the South Atlantic, en route between England and the Far East. An additional base was later available from the time when Cape Town became a British colony during the Napoleonic Wars.

Once they had been expelled from the Spice Islands by the Dutch in 1682, the East India Company instead focussed their attention on India and its textiles. A trading station was created at Bombay on the west coast of the Indian subcontinent. It had originally been established by the Portuguese but transferred to Charles II in 1661 as part of the dowry of Catherine of Braganza and rented to the East India Company for £10 per year. (Oddly, the letters patent that sealed the agreement placed Bombay ‘in the Manor of East Greenwich in the County of Kent’). In the 1690s another base was established at the commercial centre of Calcutta on the prosperous Bengali coast of India and the area was soon providing over half the Company’s imports from Asia. The original Indian base as Surat declined in importance as Calcutta, Madras and Bombay became pre-eminent. Local regulations ensured that business was conducted through intermediaries known as ‘banians’ and not directly with the producers.

By 1700 the East India Company was making 20 to 30 sailings per year to the Far East and was England’s largest corporation. The Indian subcontinent accounted for substantially more than twenty per cent of the world’s gross domestic production, compared with less than two per cent by Britain. The Bengal region in the north-east was the richest part of the Mughal empire. Its weavers had for centuries efficiently produced a vast range of the finest textiles in silk and cotton. These colourful products, such as muslin, calico, chintz, dungaree and gingham, became the East India’s primary imports into England. Business boomed and in the early eighteenth century East Indiaimported calico overtook native British wool as the most popular textile in English homes. This was to the great detriment of the local weaving industry, leading in 1697 to riots by London’s textile workers and assaults on the property of the Company and its directors. Two decades later there were attacks on London’s streets against women wearing calico. The government’s response was to restrict its importation and ban the use of powered looms in Bengal.

Between 1699 and 1774 the East India Company’s business increased to as much as fifteen per cent of total annual imports into Britain, its taxes and other payments often keeping the British government solvent. From its headquarters in London, instructions were sent around the world regarding what goods should be purchased and the price to be paid. Local Company governors in India were given autonomy as to how those purchases could be achieved.

One of the Company’s strengths was its sophisticated fleet, its handsome and heavily-armed East Indiamen equal or superior to ships of the Royal Navy, with gilded sterns and flying the Company’s striped flag. Initially it purchased existing craft but from 1610 commissioned its own ships from a yard at Deptford, next to the Royal Dockyard. As business grew, vessels of up to 1,000 tons were required, larger than could be constructed at Deptford, so the Company took the decision to create new yard. A marshy area slightly downriver on the opposite bank was chosen, by the fishing hamlet of Blackwall where Bow Creek flows into the Thames. Work began to create the yard in May 1614. It was operational within a few months, although not completely developed until 1619, by which time it was employing up to 400 workers. By then the Company operated a fleet of 10,000 tons, with 2,500 seamen. As with the royal dockyards on the opposite bank, the East India site at Blackwall was self-sufficient in all the needs of their ships, including the manufacture of its own ironwork and ropes. Employees were housed on site with their own victualling house where they could eat and drink. For security, a large wall and water-filled ditch surrounded the premises.

For customs inspections, imported goods were required to be discharged at the Legal Quays until the opening of the East India Docks in the early nineteenth century. The ships would moor at Blackwall and their cargoes would be unloaded onto 100-ton hoys to be taken upriver for inspection. From there the goods were moved to the Company warehouses in the City.

The Blackwall yard was a large fixed cost for the East India Company and when business became more difficult in the 1630s it proved to be a financial burden. After 1637 the Company ceased building its own ships and instead leased them from individual owners. The yard was sold in 1653 to a shipwright named Henry Johnson for considerably less than the Company had invested. The company did however continue to own a yard at Deptford until the latter part of the eighteenth century.

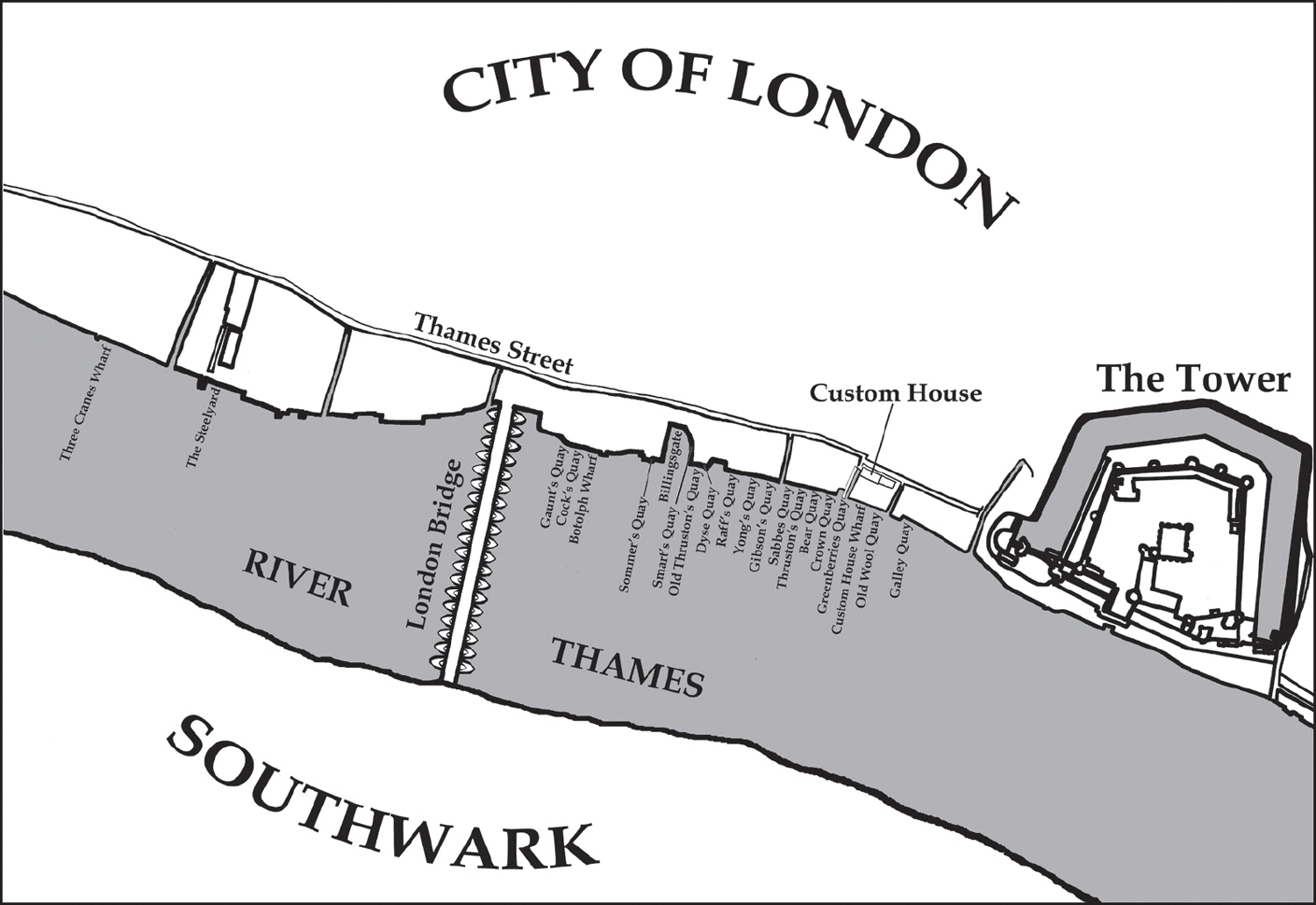

The East India merchants initially met in the City at the home of the Company’s first Governor, Sir Thomas Smythe, in Philpot Lane, before setting up nearby at Crosby Hall at Bishopsgate until 1648. ‘The East India House is in Leadenhall-Street, an old, but spacious building; very convenient, though not beautiful’ is how Daniel Defoe described their headquarters in the early eighteenth century, by then one of the landmarks of the City. In 1729 it was rebuilt to include warehouses and cellars and enlarged yet again at the end of the eighteenth century with a 200-metre neo-classical frontage decorated with statues. Its vast size included the Court Room hall, Finance and Home Committee Room, the Sale Room for auctions, and a museum and library. From East India House clerks known as ‘Writers’ produced orders and other communications in longhand using quills and written in ‘Indian ink’, the replies to which would take a year to arrive back from the Far East. To ensure their safe arrival they were written in triplicate and sent on three separate ships. From 1806 Writers were trained at the East India College in Hertfordshire and it became an alternative to university education at Oxford or Cambridge. The method of their recruitment and practices formed those of the Civil Service from the mid-nineteenth century.

The imports brought back to England were stored in the Company’s warehouses in various locations in the City. To cope with expanding business in textiles, tea, spices, ivory and other goods, a new Bengal warehouse was opened at Bishopsgate in 1771. It was incorporated into the massive Cutler Street complex, which opened in 1782. Over 640 staff were employed there in 1800.

In 1756 the young and imprudent new Nawab of Bengal seized the East India base at Calcutta. The Company’s governor retreated, leaving a small number of British to defend their position, leading to the ‘Black Hole of Calcutta’ incident. The Company had from the start operated an armed security service to defend its ships and warehouses, which evolved into a private army. The following year this small but effective force defeated the Nawab’s much greater army at Plassey (Palashi), north of Calcutta. The victory was achieved in large part through bribery of the Nawab’s commanders, as well as deceit, undertaken by the Company’s Robert Clive.

East India House in Leadenhall Street, illustrated by Thomas Hosmer Shepherd in 1829.

The East India competed against a number of other European traders in Bengal, including the VOC and the French Compagnie Française des Indes Orientales. The conditions on which the ‘kulah poshan’, or hat-wearers, could trade were imposed by the Indian rulers who ensured that business did not disrupt the fine balance of local commerce. Goods could only be purchased with silver bullion. The East India had ambitions to trade on its own terms however, without the hindrance of competition, and England was anyway at war with France. Having defeated the Nawab, the French and Dutch were largely expelled and Bengal was systematically looted of its treasures, many of which were shipped back to England. A series of malleable puppet rulers was installed, each replaced according to the Company’s needs. To increase profits an internal and external monopoly was enforced, driving out competitors, buying direct from local manufacturers, and paying weavers the minimum possible for their labours. The Company also took control of local taxes, draining the province of its wealth.

At the end of the eighteenth century up to ninety per cent of Bengal’s trade was in the hands of the East India Company. Within a decade it had reversed the direction of wealth, from India to England. Profits flowed back to shareholders, as well as the British government by way of annual payments. From its base in London, trading goods halfway around the globe, from the Orient to the eastern seaboard of North America, the East India Company was rapidly transformed into the world’s largest business entity, but it did not have the internal structures to manage its distant staff or rule a large and highly-populated nation. Corruption was endemic. Clive and his fellow executives enriched themselves through private trading. When Bengal suffered drought and famine in 1770 in excess of a million inhabitants perished while vast wealth continued to be transferred back to London. The following year Warren Hastings was appointed as Governor of Bengal and during his tenure a much greater part of India was brought under Company control. His eventual recall and trial in Westminster Hall ‘in the name of the people of India, whose laws, rights and liberties, he has subverted, whose properties he has destroyed, whose country he has laid waste and desolate’ was the most talked about event in London of 1788.

In the second half of the eighteenth century there was a dramatic increase in the size of the East India Company’s army in India and by 1806 it employed over 150,000 soldiers, with mainly British officers and native conscripts. A separate navy had been developed around the coast of India to combat piracy. During the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic wars three regiments of 1,500 Company workers were maintained for the defence of Company properties in the City of London. In 1809 a military seminary was opened near Croydon where cadets studied infantry, artillery engineering, surveying and languages.

A Company trading post was established at Singapore in the early nineteenth century under the local governor, Stamford Raffles, as part of an Anglo-Dutch treaty. Raffles was especially interested in botany and zoology and became a founder of the London Zoological Society. Under Governor-General Richard Wellesley, and the army commanded by his brother Arthur (the later Duke of Wellington), more territory in India was brought under the Company’s control. In the seventy years until the mid-nineteenth century the area of the Indian subcontinent ruled by the Company rose from just 7 per cent to 62 per cent, which also included Ceylon (Sri Lanka).

By then the Company had for some years faced strong competition within its home market. Mechanisation in Lancashire’s cotton mills meant that by the end of the eighteenth century English-woven muslin was cheaper to produce than that imported from India. Whereas at the beginning of the Company’s rule India had been the world’s leading supplier of textiles, it later became the largest importer of cotton goods from England due to lack of industrial progress. Opium, grown by the East India Company, was then its main export. India was the only source of diamonds until their discovery in Brazil in 1725 and those imported by the East India Company led to London becoming a leading trader in the precious stones. In 1849 the East India Company won control of the Punjab and its defeated Sikh rulers were forced to surrender the famous Koh-i-Noor diamond to become part of Queen Victoria’s Crown Jewels.

Tea, grown exclusively in China, overtook textiles as the East India’s most profitable commodity by the mid-eighteenth century, doubling in volume every eighteen years. The beverage was first brought to England by the Portuguese wife of Charles II. When mixed with slave-harvested sugar from the West Indies it changed the drinking habits of people in Britain as an alternative to gin and beer, transforming from an expensive luxury to an essential beverage. It was also popular in the colonies of North America. Especially large ships of 1,200 tons carried it to London, where quarterly auctions lasted up to six days, with over a million pounds in weight sold per day.

As they had in India, European merchants in China faced problems with the conditions under which they could trade. The Manchu emperor kept tight control and stipulated they must only make their purchases through local merchants at Canton on the Pearl River and pay in silver bullion. To evade the latter edict, the East India instead grew opium in India that could be used to pay for Chinese tea, silk and other exotic goods. In order to claim it was not involved in the importation of the illicit drug it was smuggled into China by private traders, with the collusion of corrupt local officials, and proceeds paid to the Company at Canton. Chinese styles caught the imagination of the British public, with porcelain and furniture made to order at workshops in Jingdezhan and Canton.

Despite the Company’s charter that gave it a monopoly of trade with all regions east of the Cape of Good Hope, much of the tea arriving at the American colonies was smuggled by merchants to avoid British taxes paid in London. In response, the government passed the Tea Act whereby taxes were instead paid locally in North America. Colonists resented the payment of taxes without representation. In December 1773 tea from three East India Company ships was dumped into Boston harbour, signalling the start of the American War of Independence.

In the early seventeenth century a return voyage to the Far East would take about two years but by the end of the eighteenth century that had been reduced to an average of 114 days. In the times of sail, East India ships left Blackwall each January in order to be in time for the winds required to carry them across the Indian Ocean. Convoys gathered in mid-stream at Gravesend where live animals and victuals were taken on board for the journey and passengers and outbound Company staff and soldiers embarked. It was not unknown for ships to perish at the very first or last stage of their journey, grounded on the sands around the Kent coast. The worst such incident occurred in January 1809 when three East Indiamen headed for Madras were lost on the Goodwin Sands.

Iron steamships were introduced in the Company’s last decades and thereafter they could sail at any time of the year. ‘Blackwall Frigates’ were introduced, carrying passengers and mail as well as cargo. Sailing ships continued to be active long after the East India’s trading days were over however, particularly with the introduction of the fast clipper-style ships that brought tea to London in record time. The journey was shortened further with the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. General ships’ crews tended to be recruited from amongst London’s poor but many died on the outward journey so locals were often employed for the return. These were known as ‘lascars’, a word first used by the Portuguese to describe any Asian crew. Arriving in London in the autumn they had to survive the cold, often without lodgings, until embarking on an outbound ship early the following year. By the end of the eighteenth century they were a common sight on London’s streets.

In order to provide a degree of accountability and combat corruption within the Company the government passed the India Act in 1784. The charters that provided the East India Company with its monopolies on business with India and China were renewed by the British government every twenty years. By the time the India charter came up for renewal in 1813 there were many calling for the liberalisation of trade and the monopoly of 200 years finally ended. Thereafter the Company continued to govern in India as an agent of Parliament. The China monopoly ended in 1833.

With the ending of the monopolies, the Company shared its business in the Far East with aggressive independent merchants such as the Scotsmen William Jardine and James Matheson who joined the triangular opium and tea traffic. After 1834 the East India no longer imported tea from China but continued to grow the opium in India that fed the trade. In the meantime they finally infiltrated the Chinese tea-producing areas to learn the secrets of its cultivation. Following the East India’s conquest of the Assam region of India, local varieties of the tea plant were discovered and Company plantations created there, the first harvest arriving in London in 1839.

Areas of the Indian sub-continent controlled by the East India Company during the nineteenth century.

In 1857 the Company’s Bengal Army mutinied, leading to a general uprising in India. The savage war lasted for two years, after which Parliament decided it was time for a change in the governance of the subcontinent. The East India was stripped of its administrative powers and replaced by the British Raj, managed from the magnificent new India Office in Whitehall. Queen Victoria became Empress of India and the Company’s forces became the British Indian Army. The head office in Leadenhall Street was demolished in 1861. Shareholders continued to be paid a guaranteed dividend until being bought out in 1873 at the expense of Indian taxpayers.

During its nearly 260-year existence the Honourable East India Company, often called ‘John Company’, went through four phases. First it brought spices directly from the Far East. In its second phase it revolutionized the fabric industry, bringing cheap, quality cottons and silks to Britain. Next it changed the drinking habits of the nation, with tea from China. Finally, it ceased to be a commercial operation but continued as the administrator of large parts of the Indian subcontinent. At its best it was highly efficient and the world’s largest trading organization, directly employing 4,000 workers in London alone. Yet the large-scale corruption and its voracious appetite for excessive profits without accountability led to the plundering of the Indian economy and the near-enslavement of its people, opium addiction of huge numbers of Chinese, and a part in the loss of Britain’s American colonies. To this day, Bengal, once one of the wealthiest regions of the world, remains one of its poorest.

The combination of the growing British Empire around the world and the Industrial Revolution at home had a profound effect on the Port of London. New methods of producing iron and the introduction of the steam engine brought mechanization on a massive scale, while the creation of canals allowed materials and goods to be transported in large quantities around the country. Raw material could be imported from the colonies. New types of product, or ones that could be machine-finished more economically in mass quantities, could be exported in return. Britain was on its way to becoming the ‘workshop of the world’ and by the mid-nineteenth century was producing forty per cent of the world’s manufactured items.

The wars against the French during the reigns of William III and Queen Anne gave a great impetus to the growth of colonies and trading posts, particularly in North America and the Caribbean, Africa and the Far East, and a greater influence in the Mediterranean with the new possessions of Gibraltar and Minorca. The establishment of the Bank of England in 1694 laid a financial foundation for Britain as a great nation.

France and the Low Countries had long been the major western European mercantile nations but from the end of the seventeenth century Britain overtook the Netherlands to become an equal of France in what became known as the ‘commercial revolution’, a phrase coined by Viscount Bolingbroke in the 1730s. In the 1690s France took the decision to focus its military efforts on its land campaign, concentrating resources on the army rather than large warships, effectively giving up control of the seas. By 1715 Britain’s navy of 182 ships in excess of 300 tons was larger than the French and Dutch navies combined. A larger navy helped to protect merchant shipping as well as assisting the growth of the empire by means of ‘gunboat diplomacy’.

The Navigation Acts introduced by the Commonwealth Parliament and under Charles II did much to shift trade away from foreign to English ships and crews, as well as Scottish after the union of 1707. In 1600 half the ships entering London were English but by the 1680s that had risen to seventy-five per cent.

Although London was by far the biggest British port there were others benefitting from the increased trade. The new Atlantic routes benefitted towns on the western side of Britain. Liverpool grew from nothing to become the largest port in the north west by the end of the seventeenth century due to exports of cloth and salt. Bristol benefitted from imports of sugar, and fish from Newfoundland. Exeter became a major exporting port for cloth. Glasgow and Whitehaven in Cumbria also grew rapidly in size. On the east coast, shipments of coal from Newcastle rose dramatically in order to feed the growing demand from London and elsewhere and Hull became prominent. There was a fivefold increase in the amount of shipping passing through the Port of London between the beginning and end of the seventeenth century. Yet at the same time certain trades were moving away from London, such as tobacco in which the capital had an 80 per cent share in the middle of the seventeenth century, falling to 50 per cent in the 1680s in the face of rivalry from other ports.

Initially London was the leading port in the triangular slave trade in the early part of the eighteenth century. Ships would leave Britain bound for Africa where goods were traded for human cargo that was then taken to the Caribbean. They returned from there to Britain loaded with sugar and tobacco. Later in the century Bristol, and then Liverpool, became the prominent ports for this trade.

All the major European nations were at war with each other for a sixty year period from the second half of the eighteenth century. At the end of the Seven Years’ War between 1756 and 1763 Britain had greatly enlarged the territory that it controlled in America, the Caribbean and India, either directly or through the East India Company. France lost almost all its vast territories in America and India to either Britain or Spain. Australia, New Zealand and Western Canada began to be colonized by Britain following James Cook’s voyages around the Pacific in the latter eighteenth century. At the conclusion of the French Revolutionary War and Napoleonic Wars between 1793 and 1815 Britain was left as unquestionably the greatest European power, with an empire that spanned the globe, patrolled by the world’s strongest navy and financed by a manufacturing economy.

The growth of international shipping created an increasing market for finance and marine insurance. London’s merchants, financiers and marine insurance underwriters were primarily based at the Royal Exchange. At the turn of the eighteenth century specialist financial traders also began to congregate at certain coffee houses.

At the very end of the seventeenth century insurance underwriters met at Edward Lloyd’s coffee house in Lombard Street to gather information and do business with one another. Information began to be published and read out from a pulpit within the coffee house on sailings and maritime disasters, which continued as ‘Lloyd’s List’ after Lloyd’s death in about 1713. In 1760 an association of underwriters was formed to set up a scheme to classify ships according to their condition in order to better quantify their risk. The result was the annual Lloyd’s Register of Shipping which was first published in 1764, listing merchant vessels according to their name, home port, master, tonnage and equipment. A classification was devised to denote the condition of the ship according to the association’s surveyors. As the organization began to expand internationally, surveyors were recruited around the world.

Official ship registration began in Britain from the seventeenth century and was the responsibility of customs officers. It was not until 1786 however that registration became fully obligatory for decked vessels above fifteen tons. In the latter part of the century around 200 large ships of over 360 tons were registered at London but also many smaller vessels.

Businessmen at coffee houses such as Garraway’s and Jonathan’s bought and sold commodities. At the latter, shares in joint-stock companies were traded after stockbrokers were expelled from the Royal Exchange in 1697, eventually leading to the establishment of the London Stock Exchange in 1802. Maritime merchants, ship brokers and ship captains met at John’s on Birchin Lane, established in 1683, where ship auctions were held. Traders in goods from the American colonies met at the Virginia Coffee House, behind the Royal Exchange. The business of these merchants was to match cargoes with available ships arriving and departing from the Port. They were gradually joined there by brokers in merchandise to and from the Baltic and in 1744 the establishment changed its name to the Virginia and Baltick Coffee House. There was much risky speculative dealing in the 1820s and the brokers regulated their business. In 1823 a committee of brokers and merchants was formed; membership was restricted to 300 and a new headquarters established, known as the Subscription Room. This later evolved into the Baltic Exchange.

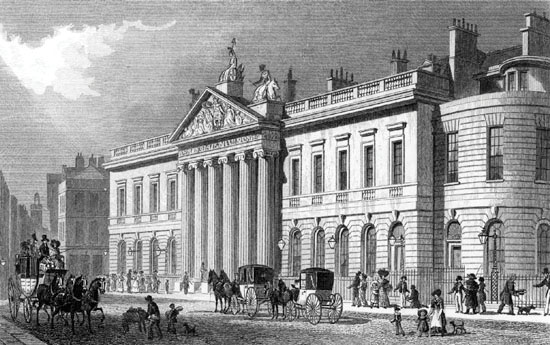

At each major English port the officials responsible for collecting duties on behalf of the monarch were based at a building known as Custom House. At the Port of London it has always been located on the riverside immediately upstream of the Tower. The first recorded building was constructed at Wool Quay by the Sheriff of London in 1385 during the reign of Richard II. The poet Geoffrey Chaucer, Comptroller of the Customs of Wools, Skins and Tanned Hides from 1374 until 1386, was based there for his work as manager of tax collectors.

Those officials appointed as collectors and controllers during the midfifteenth century were from amongst London’s leading merchants and stayed in their posts for short periods, often then rising to higher civic offices. The senior London customs officials during the latter years of Edward IV and reign of Henry VII, however, were royal servants who held their positions for many years.

The medieval Custom House was rebuilt in red brick in 1559 with three storeys, of which the lower level was an open arcade. Inspectors from Custom House known as ‘tide-waiters’ boarded each ship as it arrived to obtain a certificate of the vessel’s cargo, to be recorded at Custom House and the duty calculated. With confiscated goods stored inside, often of a flammable nature, fire was always a danger. When the Elizabethan property was destroyed in the Great Fire it was the first building that Charles II proposed to be rebuilt from public funds and the King surprised everyone by appointing Christopher Wren, a professor of astronomy from Oxford, to oversee the work, his first design project in London.

Custom House in the early nineteenth century prior to its rebuilding by Robert Smirke. This engraving first appeared in Bernard Depping’s L’Angleterre, ou Description Historique et Topographique de Royaume Uni, published in Paris in 1824.

Wren’s building was in turn devastated by fire in 1715. Its replacement, designed by Thomas Ripley, was constructed in a U-shape around a courtyard. Daniel Defoe wrote of it: ‘As the city is the centre of business, there is Customhouse, an article, which, as it brings in an immense revenue to the public, so it cannot be removed from its place, all the vast import and export of goods being, of necessity, made there … The stateliness of the building, showed the greatness of the business that is transacted there: the Long Room is like an Exchange every morning and the crowd of people who appear there, and the business they do, is not to be explained by words, nothing of that kind in Europe is like it.’

With growing trade in the port, and being somewhat dilapidated, a larger building was already being planned when it met the fate of its predecessors in 1814. Surrounding properties east of Billingsgate were purchased for the larger site with a waterfront almost 150 metres long. Much of the current building, completed in 1817, was designed by David Laing, Surveyor to the Customs and a pupil of John Soane, featuring a much-praised triple-domed hall in a French style. Unfortunately Laing had not foreseen that the piling underpinning the building had been poorly and fraudulently carried out by a contractor and in 1824 part of the river façade and the floor of the main hall collapsed. By then such work was the responsibility of the Office of Works and their surveyor Robert Smirke was commissioned to put things right. He created a new façade featuring Ionic columns that remain today.

In the early nineteenth century the ‘tide-waiters’ boarded inbound ships at Gravesend and stayed on board until their cargoes were discharged in the Port. In the docks and wharves ‘landing-officers’ took note of goods as they came ashore and once duties were paid a receipt was given. This information was then taken to the Long Room at Custom House. The system was modified in later decades whereby the master of each ship arriving or leaving the Port was obliged to attend the Long Room to report on its cargo and necessary payment made. In 1840 London’s Custom House collected almost half of the total duties from the United Kingdom’s ports. Throughout that century customs duties were progressively simplified. In 1853 there were over 1,100 rates of duty, yet most income came from just a small number of types of goods. Towards the century’s end the number of rates had been greatly reduced and focussed on those imports that created most income, namely tobacco, spirits, tea and wine. Ships’ masters today no longer arrive at Custom House to pay their duties but the building remains a rather grand office of HM Revenue & Customs.

Immediately to the east of the Tower of London lay the Precinct of St Katharine, to which we will return in the next chapter. Further east still, the hamlets directly on the north bank were quite isolated from the city and surrounding districts until at least the sixteenth century. They were most easily reached by boat and evolved into communities employed in maritime industries, looking outwards to the river.

In Anglo-Saxon times a church dedicated to St Dunstan was established in the manor of Stibenhede. The village of Stepney, as it later became known, gradually grew in all directions around it, including down to the riverside hamlet of Ratcliff where Stepney’s port developed, with cottages inhabited by fisherman and ferrymen.

Most of the nearby area had been marshy until the Middle Ages. It was then held by the bishops of London and in the reign of Edward II their bondmen converted much of Stepney Marsh – the Isle of Dogs – to meadow, with the alluvial deposits making it a rich pastureland. There were serious floods at various times, the most significant in March 1660. Three days after it occurred Samuel Pepys was passing by boat and recorded: ‘… in our way we saw the great breach which the late high water had made, to the loss of many 1000l [£1000] to the people about Limehouse.’

The process of draining Wapping Marsh, between Ratcliff and St Katharine’s, was undertaken in the early sixteenth century when Cornelius Vanderdelft, a Dutchman with specialist knowledge in land drainage, was commissioned to oversee the task. A wall of built-up ground as high as eight or nine feet above the level of the land was created along the riverside and drainage ditches dug across the low ground. Cottages and workshops developed along the water’s edge, creating the hamlet of Wapping-in-the-Wose (‘in the marsh’), with each householder responsible for maintaining the wall. The buildings were constructed in precarious and rickety fashion overhanging the wall, interrupted by numerous stairs down to the river, forming the street of Wapping Wall, as well as Foxes Lanes (now Glamis Road). Similarly, causeways higher than the surrounding fields were created with buildings along them. Thus Wapping evolved as a river-facing community, otherwise isolated by its surrounding marsh.

The riverside communities were connected by a country lane, which in the time of Elizabethan historian John Stow developed into the road known as Ratcliff Highway, north of which lay open countryside. By then there were hamlets around the northern part of the Isle of Dogs. ‘Of late years shipwrights and, for the most part, other marine men, have built many large and strong houses for themselves, and smaller for sailors, from thence also to Poplar, and so to Blackwall,’ Stow recalled.