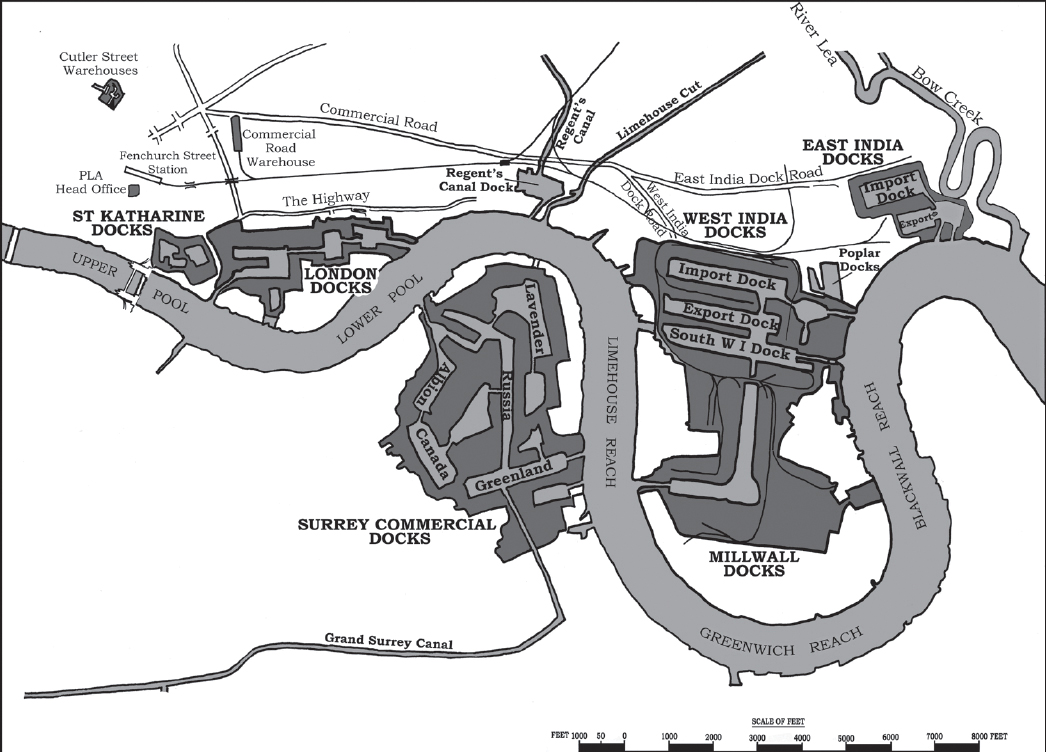

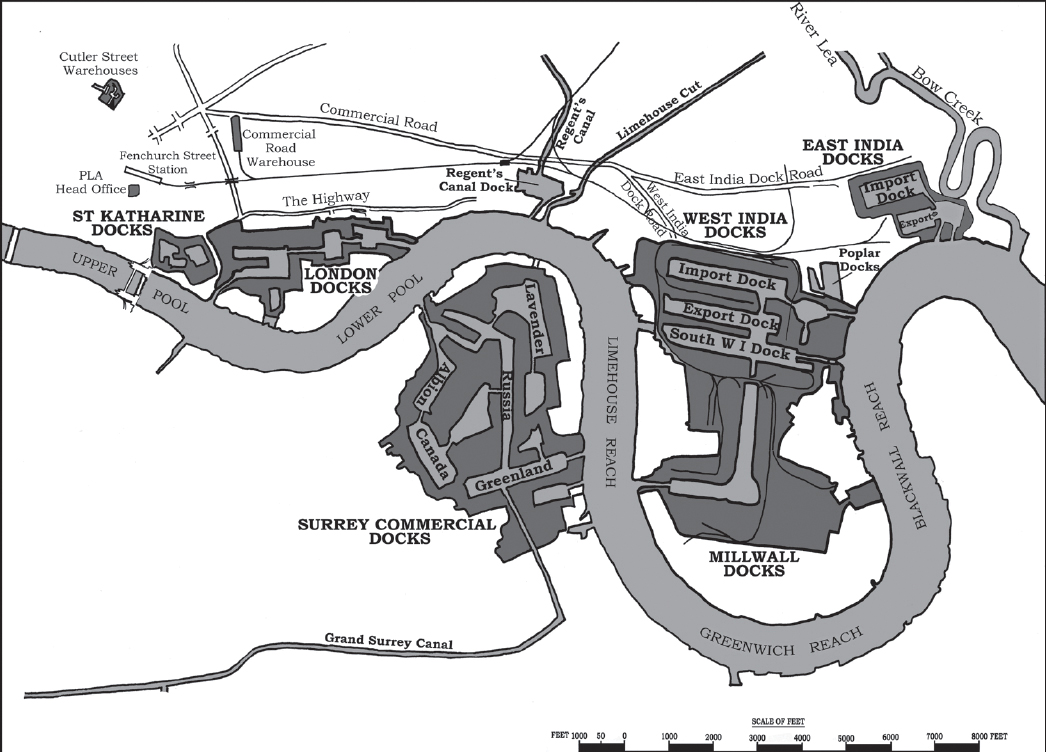

The Upper Docks shown at their greatest extent, which was reached in the latter part of the 19th century.

The change from wooden-hulled sailing ships to iron and then steel steam ships in the second half of the nineteenth century meant that fewer vessels could carry a far greater tonnage of cargo. Prior to the First World War British-registered ships accounted for over a third of the world’s total ocean-going tonnage, the largest of any nation by a wide margin. In 1815 the British merchant fleet consisted of nearly 22,000 ships, but in the early twentieth century less than 21,000 British ships carried almost five times more tonnage. Not only could greater loads be carried but they arrived faster, more predictably and at cheaper rates.

The Port of London had long been the largest dock complex in the world, handling the greatest volume of cargo, with a storage capacity of one million tons and over nine million tons of foreign cargo passing through in 1899, a third of all goods arriving in the country. This pre-eminence continued into the following decades until around 1913 when it was surpassed by Hamburg and then New York. In the early twentieth century the port was the biggest employer in the capital, with 20,000 men working in a wide variety of jobs and half as many again seeking casual work at the gates each day. Furthermore, the docks had become surrounded by manufacturing industries of many kinds, producing everything from domestic gas and electricity to consumer goods.

Ever larger ships had cut voyage times around the world, helped by the opening of the Suez Canal in 1869. The requirement for larger docks and harbours to accommodate these vessels concentrated Britain’s maritime trade on a limited number of locations. At the end of the nineteenth century the largest of the country’s ports were London and Liverpool. They were followed by Newcastle and Cardiff, both of which had a strong coal trade, the latter changing from a small harbour into the world’s largest coal port. By the start of the Great War in 1914 Southampton had become the fifth largest port. In addition to cargoes, large passenger liners were sailing according to fixed timetables across the Atlantic and to other parts of the world, particularly from Liverpool and Southampton.

During the eighteenth century, exports from the Port of London exceeded imports but that had dramatically reversed by the early part of the twentieth century. In 1913 the value of imports was £253,879,000 but that of exports only £157,913,000. The principal incoming goods by value were wool, tea, rubber, metals, timber for construction, sugar, meat and butter. The major exports by value were cotton and woollen clothing, machinery and metal products. Around two thirds of the volume carried by British ships was with Europe and about a fifth with the Americas.

At the start of the twentieth century the complex of docks and wharves and the forest of cranes of the Port of London were symbols of the nation’s wealth. A map of the city’s principal businesses created in 1904 for the Royal Commission on London Traffic showed a continuous belt along the Thamesside, from Barking in the east to Brentford in the west. Wharves and factories had developed along all the navigable tributaries of the Thames, including the Wandle, Deptford Creek and Ravensbourne, Bow Creek and the Lea, Barking Creek and the Roding, as well as London’s canals. Yet despite the great size of the Port, the vast amount of cargo that passed in and out, the large workforce, and its national importance, it was failing for both its shareholders, who were receiving a poor return in dividends, and the workers, many of whom lived on the breadline. London was becoming less reliable and cost-effective for shipowners. Business was going elsewhere, particularly to Liverpool, which was more convenient especially for the North Atlantic routes, or to Continental ports, some of which were subsidized by their local governments. The larger ocean-going ships had become so big that silting of the river meant that few could reach the upper docks and the Pool of London, all of which were restricted to small coastal steamers and lighters. Dock companies were therefore reluctant to invest in larger entrance locks for ships that were unable to navigate upriver, while the Thames Conservancy saw little point in dredging if ships could not pass through the small locks.

In the late eighteenth century the main issue at the Port had been the lack of facilities for berthing and unloading ships, leading to lengthy delays and congestion. The government set up a commission to consider the problem at that time, leading to the creation of docks owned by individual companies. A hundred years later there were too many docks of the wrong kind, a lack of coordination between the multitude of docks, and no effective authority to manage the river. In 1900 the government once again set up a royal commission to consider the problems. During their investigation the eminent commissioners made visits to London’s docks and wharves, as well as other major British ports, and made enquiries of Continental ports such as Hamburg and Rotterdam. One hundred and fourteen witnesses were questioned over thirty-one days.

Some of the findings during the review process were that the facilities in the port were outdated because of lack of investment; the river was too shallow to allow ships to reach the upper docks and wharves due to neglect by the Thames Conservancy; there were divisions of responsibility that obstructed improvement of the Port; the turnaround times for loading and unloading ships were too slow; railway connections were poor; and docking charges were too high. The docks were not up to modern standards but the commission believed they were capable of further development. The recommendation, published in June 1902, was that a single public authority should be created to manage both the docks and the river from Teddington down to the sea. The concluding words of the lengthy report included:

The deficiencies of London as a port, to which our attention has been called, are not due to any physical circumstances, but to causes which may easily be removed by a better organization of administration and financial powers. The great increase in the size and draught of ocean-going ships has made extensive works necessary both in the river and in the docks, but the dispersion of powers among several authorities and companies has prevented any systematic execution of adequate improvements.

The London & India Docks Joint Committee had done little during its tenure to improve their estate other than enlarge the Blackwall and South West India entrances of the West India Docks. They had, however, greatly increased the importation of frozen meat, with the addition of several specialized warehouses at the Royal Victoria. Perhaps to show they were not yet a dead force, or possibly wanting to enhance their takeover value in the case of their demise, they cut maintenance budgets, reduced wages, increased shipping dues by fifty per cent and submitted a plan to Parliament to extend the Royals with a large new deep basin to the south of the Royal Albert Dock.

It was too late. The government considered the problem and began the process of nationalizing London’s docks. The creation of the Port of London Authority was introduced in the King’s Speech at the Opening of Parliament in November 1903. It was then delayed for several years as discussions took place about how the Port should be organized. There were those who believed the plans were a dangerous move towards socialism. Some advocated creating new, more efficient and cheaper wharves instead of upgrading the enclosed docks. The first attempt at a Bill was abandoned by the Conservative government. In the meantime, alternative Bills were promoted by the London & India Docks, the Thames Conservancy and London County Council, and another was for the amalgamation of the London & India and Millwall companies.

In the summer of 1906 David Lloyd George, President of the Board of Trade in the new Liberal government, visited some of the Continental ports to investigate how they were managed. He came to the conclusion that a single nationalized authority was indeed the best solution and that the docks should be retained. He proceeded to strike a deal with the dock companies and the Port of London Act was passed in December 1908 despite some opposition. The final acquisition of the London docks and their storage facilities was concluded under Lloyd George’s successor at the Board of Trade, Winston Churchill.

The management of the tidal River Thames and its docks were assigned to the Port of London Authority, which began operating in March 1909, and was accountable to the Board of Trade. It was headed by a Board consisting of between 15 and 28 members representing all the various interested parties, including the government, shipowners, wharfingers, lightermen, London’s public authorities, Trinity House, the National Ports, the Admiralty and the workers. Up to four of the members could be nominated by the London County Council, two each by the City of London and Board of Trade and one each by the Admiralty and Trinity House. One each of the LCC and Board of Trade members were to represent the labour force.

Following the example of the Mersey Docks & Harbour Board, the PLA was created as a non-profit, self-governing trust in which any excess revenues would be used to improve the river and port facilities or to reduce charges. It was empowered to raise up to £5 million in fixed-interest-bearing stock to acquire the docks. Income came from rates on goods entering and leaving the Port, the licensing of craft, and on various services such as loading, unloading and storage.

The Authority took on obligations for maintenance of the river channels, provision of moorings, regulation of river traffic, the licensing of wharves, the removal of wrecks, and the prevention of pollution. It took over the duties of the Thames Conservancy on the Lower Thames, the latter thereafter having responsibility only for the upper, non-tidal river. Registration of licensing of craft, watermen and lightermen was taken from the Watermen’s Company. Responsible for sixty-nine miles of tidal river downstream from Teddington to the Thames Estuary, the PLA had the authority and scope to solve many of the long-term problems, including dredging the river and regulating dock labour.

The PLA inherited almost 3,000 acres of estate, including that of the London & India, Millwall, and Surrey Commercial companies, with 32 miles of quays, as well as 17 London County Council passenger piers. The numerous riverside wharves remained in private hands. Towage within the docks was the responsibility of the Authority although on the open river it remained in the hands of private tug companies. At the time of its creation it employed over 11,000 people, almost all of them men. Most were ordinary dockers for cargohandling but there were also those with specialist skills and training such as dockmasters, stevedores, timber porters, barge-handlers, coopers, divers and inspectors. Others undertook clerical work in the offices or packed and bottled. Over 1,000 worked in the headquarters and dock offices, more than 7,000 as permanently employed dock-workers, plus an average of around 3,000 casual labourers hired each day. The number of workers had increased by 1911 to over 13,000, remaining fairly constant until after the Second World War.

Several other bodies continued in their responsibilities alongside the PLA. Trinity House retained jurisdiction over pilotage on the river as well as for buoys and lighting. The City of London continued to deal with health issues regarding ships, passengers and cargoes. The Free Water Clause that was written into the Act of Parliament, which allowed lighters to freely enter each dock to load and unload overside, remained in place. However, each lighter was thereafter required to pay a registration fee.

Security on the Thames had been the responsibility of the Marine Police Establishment since its creation in 1798, which was later incorporated into the Metropolitan Police. Within the enclosed docks the dock companies employed their own security until the late-nineteenth century. When the PLA was established it held discussions with the Metropolitan Police regarding them taking over responsibility within the docks. The matter could not be resolved, and Tilbury Docks were anyway outside the Met’s area, so in 1910 the PLA created its own police force and ambulance service. A Criminal Investigation Department was formed in 1913. A PLA police HQ was opened at the main entrance to the West India Docks. The hours were long and the pay was low; the police force was not particularly well-motivated or effective so theft by dockers was common and in the early years many officers were dismissed for being intoxicated or smoking while on duty. It was relatively easy for workers to carefully open a packing crate, steal some of the contents, replace them with an object of equal size and then reseal the crate. Pilfering was considered part of the way of life within the Port, to which it seems a blind eye was turned by the authorities. As has been mentioned in an earlier chapter, having a ‘waxer’, a sample of alcohol from the vaults, had a long tradition.

The first chairman of the PLA was the energetic and forceful Sir Hudson Kearley MP, which he undertook in an unpaid role. As Parliamentary Secretary to the Board of Trade he had been responsible for steering the Port of London Act through the House of Commons. Starting work at 16 for the Tetley tea company, he made his fortune as the founder of the tea importer Kearley & Tonge and the International Stores grocery retailer, which had 200 branches. He was elevated to become Lord Devonport in 1910.

As part of a move to create a strong and unifying public image, a coat of arms was approved by King Edward VII, including the motto Floreat Imperii Portvs (May the Imperial Port Flourish). The Board of the PLA initially met at the former Leadenhall Street offices of the London & India Dock Company. They had inherited the East India Company warehouse at Crutched Friars and obtained powers to clear the surrounding area containing eighteenth century houses, the whole to be used for the creation of a new headquarters. The leading architect, Sir Aston Webb, organized a competition for a design and the one chosen was from Edwin Cooper. John Mowlem & Company began construction in 1913 but there were delays from the start, not improved by the outbreak of war. Lord Devonport laid the foundation stone in June 1915 and the building was finally opened by the Prime Minister, David Lloyd George, in October 1922. After several increases in the budget, the final cost was over £2 million. Occupying a complete City block, the imposing building still stands beside the Trinity House headquarters, looking down Tower Hill onto the Tower of London and clearly seen from the river. Cooper’s clever design consisted of a rectangular square, cut back at forty-five degrees on one corner to give an elevation facing Trinity Square. The grand classical entrance featured Corinthian columns, three storeys high, topped with a massive tower featuring a giant figure of Father Thames. A huge rotunda, with a larger diameter than the dome of St Paul’s and claimed to be Europe’s largest unsupported concrete dome, stood within the central atrium, connecting to offices on the four sides and maximizing light internally. For decades the Trinity Square HQ housed large numbers of bowler-hat-wearing clerks, female typists, and telephone operators, who rarely, if ever, visited the docks. Previously communication between the many PLA staff, located over a large area, had been undertaken by the Authority’s own uniformed messenger boys. A telephone exchange was installed in the headquarters from the beginning and it had an extensive network that linked it to the docks.

The PLA’s first Chief Engineer was Frederick Palmer, who had held the same position at the Port of Calcutta. He was tasked with proposing plans for works to make good on previous neglect and to upgrade the PLA’s docks. In his report submitted to the Board in December 1910 he divided the plan into three programmes based on their importance and urgency, with the total cost estimated at £14,426,700. It was Lord Devonport’s opinion that priority should be given to the West India Docks – close to the City and with excellent warehousing but with limited use due to the small size of its entrance locks and shallow depth – and the Royal Docks. He considered Tilbury to be too far away, beyond the cartage area of London, to be of importance. Simultaneously undertaking all the work of the first programme would have created much delay to shipping, so what was approved varied from Palmer’s plan from the start. In particular, much of the work proposed for the West India Docks had to be delayed in order to minimize disruption to the Port, despite the priority given to it by Lord Devonport. Contracts were soon being put out to tender for a number of projects, the first being the East India and London Docks, where, when completed, shipping could be diverted while the more important work at the West India took place. As the work was getting underway Britain declared war on Germany and that was to cause serious disruption to the plans.

The older of London’s docks had been constructed at a time when ships had round hulls and thus quay walls were curved. By the twentieth century ships had straight hulls and deeper drafts, with the result that they could not moor directly against older quaysides. As part of the new works, a false, vertical wall was constructed in front on the curved quay wall at the North Quay of the West India’s Import Dock. New concrete transit sheds replaced the existing dilapidated timber-built facilities. The first section of this work was completed in October 1914 but thereafter work slowed due to the war and the entire project was not completed until May 1917. Similar work was carried out at the West India Export Dock and the lock between the East India Import Dock and Basin was widened to eighty feet. By far the cheapest tender came from a German company, who carried out the initial work, but the contract had to be transferred to a British firm at the outbreak of war and the work completed in 1916. Additionally, the width of the North and East Quays of the Import Dock was increased by twenty feet and new transit sheds constructed, three on the North Quay and one on the West Quay.

The North Quay of the London Docks was reconstructed using reinforced concrete, replacing the early nineteenth century wooden sheds with two-storey sheds, built onto a concrete-framed false quay in front of the existing dock wall. A new electric crane was installed. The size of ships entering the London Docks was still limited to 2,000 tons by the small 45-foot-wide entrance lock at Wapping and the Tobacco Dock Passage. By widening the passage, bigger ships could enter via the larger Shadwell New Entrance. This work was completed and the passage in use in April 1915 and, as it was taking place, a new reinforced-concrete jetty was constructed to replace the old timber jetty in the Western Dock.

The Tilbury Docks had originally been opened for the use of larger vessels but, as they continued to increase in size, the modern ships of the early twentieth century were having difficulty manoeuvring in and out of the three parallel docks. It was therefore decided in 1912 to extend the Main Dock, providing three new berths, together with sheds on the South Quay. The initial work proved to be difficult due to pressure from ground water. The solution was to sink fifty-three large concrete monoliths into the ground to form the quay walls. The change in construction method delayed the work, which was completed in 1916.

It was proposed to replace the equipment at some of the impounding stations that pumped water and regulated levels within the docks in order to provide greater depth. A new impounding station was completed at the Victoria and Albert Docks prior to the war; it was followed by those at the London Docks, in use by January 1915, and the East India Docks.

A cold store was built for the PLA at Smithfield market in the City and completed shortly after the outbreak of war. In 1913 work commenced on a large cold store with a reinforced-concrete frame at the Royal Albert Dock for the sorting of frozen meat from New Zealand. Work slowed during the war, the contractor went into liquidation in 1916, and the PLA completed it in 1918 using direct labour. Forty-three electric cranes were installed at the Albert Dock, which could lift substantially greater loads than those they replaced, and new timber sheds were created at the Surrey Docks.

There was concern owing to the poor state of the Port’s dry docks, which could cause business to go elsewhere, so several new ones were planned. Millwall Dry Dock was lengthened to 550 feet and new pumping equipment installed, completed in March 1913. The Western Albert Dry Dock was enlarged to 575 feet in length by 80 feet in width, with new pumping equipment that reduced emptying to three hours.

In the opinion of Edward Sargent of the Docklands History Group: ‘The PLA works programme was breath-taking in its scale and conception and would have undoubtedly made the Port the premier port in the world.’ Although much modernization and improvement was achieved in the first few years, Palmer’s original plans were heavily curtailed by the onset of war in 1914.

The Upper Docks shown at their greatest extent, which was reached in the latter part of the 19th century.

No doubt it was hoped that the inclusion of James Anderson of the Amalgamated Stevedores’ Union and Harry Gosling of the Lightermen’s Union on the Board of the PLA would lead to greater harmony and inclusiveness across both sides of Port employment. Yet labour relations remained as fractious as in the days of the private dock companies. Much of the time of PLA committees became devoted to points regarding wages and related issues rather than improvements to the Port and the increase of business. The Dockers’ Union, still headed by Ben Tillett, formed an affiliation with the National Union of Dock Workers, National Sailors’ and Firemen’s Union and fourteen other unions in 1910 to form the National Transport Workers’ Federation, with Gosling as president and Anderson as general secretary.

The following July, taking advantage of a shortage of labourers, the Dockers’ Union, supported by the other members of the NTWF, made a demand for an increase in the hourly rate from six pence to eight pence, other improved conditions, and formal recognition of all unions. For the first time, on one side of the negotiating table sat the united port workers led by Gosling and on the other all the employers represented by the PLA and its chairman, Lord Devonport. Gosling was a lifelong Thames man, whose father, grandfather and great-grandfather had all been lightermen. A naturally gentle man, he was highly respected by the port workers. With the employment situation as it was, the employers were in no mood for a fight and made concessions in what was called the Devonport Agreement. Under this plan the hourly day rate was increased to seven pence and overtime from eight to nine pence for various types of ordinary dock work, as well as a decrease in the length of the working day. The NTWF leadership’s agreement however was rejected by their own members who demanded an extra penny an hour. Gosling and Tillett, though recommending acceptance, were voted down at a mass rally and were forced into calling a strike. It was a repeat of the 1889 strike, with daily processions through the City, ending at either Tower Hill or Trafalgar Square. There were calls for troops to be sent in to clear incoming food that was blockaded in the docks but they were resisted by Home Secretary Winston Churchill. Devonport famously declared that he would prefer to starve the men back to work, to which Tillett declared at a mass meeting on Tower Hill, ‘Oh God, strike Lord Devonport dead.’ After a month the union funds were exhausted and the government stepped in as conciliator. The workers returned to work on the terms of the Devonport Agreement but issues remained unresolved, in particular regarding the call-on. Union membership collapsed after the strike. The PLA henceforth held the call-on inside the dock gates, without a requirement to be a union member. They refused to reinstate striking workers on a permanent basis and instead continued to employ many blackleg workers used during the strike. They did however take on as permanent staff 3,000 casual workers.

London was the largest city in the world as well as the leading manufacturing centre in Britain at the beginning of the twentieth century. When Britain went to war with Germany from August 1914, factories that made certain products switched instead to making munitions, or those producing garments to military uniforms. Economically, and leaving aside the great loss of lives of those who went to fight, London generally prospered from the Great War of 1914–18.

In the first years of the conflict, trade in the Port rapidly increased. Continental ports closed and shipments from allied countries were diverted to London. Troops and supplies were also being ferried to France from the Thames. The Port’s warehouses were soon unusually full with produce. There were so many vessels coming and going in the first months that there was congestion, with queues of ships at anchor in the Thames Estuary waiting for berths. Fortunately, at around that time, improvements initiated by the PLA at the East India, London, West India and Tilbury Docks were coming to fruition to ease the situation. As labour became scarce, dredging of the river ceased early in the conflict.

The PLA was directly employing around 4,500 men prior to the war and that increased to 8,000 in 1915. With the port so important to the war effort, workers were selectively exempted from being drafted into the armed services. Many anyway signed up or left to work in local munitions factories where high wages were on offer. Over 1,200 were enlisted to assist in French ports. To best regulate traffic throughout the country, the Port & Transit Executive Committee was formed in November 1915, with Lord Inchcape as chairman. One of its initiatives was to form mobile Transport Workers’ Battalions, consisting of soldiers, to provide labour whenever there was a shortage in a port. On occasion as many as 1,000 men from the battalions were employed in the Port of London.

In October 1914 the PLA’s engineers were requested to create a temporary pontoon bridge across the Thames at Gravesend, supported by seventy lighters, to prevent enemy ships entering the river. It opened to shipping for three hours on each high tide. Torpedo nets and booms were also set up at dock entrance locks. The Admiralty sought additional equipment in the Port’s dry docks for the repair of ships damaged by torpedoes but the PLA’s facilities were at that time intended primarily for painting and cleaning. Following negotiation it was agreed that the Admiralty would pay half the cost of the equipment. Security of the Port became even more important during the war. It was a task entrusted to the PLA police force who worked together with government Alien Officers. Of particular interest were foreign nationals, especially sailors arriving on alien vessels.

Britain had a superior navy and, despite some setbacks and losses, generally kept the German surface fleet in check. Much of the nation’s food and raw materials were imported, all of that arriving by sea, and it was therefore vital that the enemy was not able to blockade the ports. Understanding the importance of the Port of London to Britain, it became the target of Zeppelin air raids from the summer of 1915. The giant airships were notoriously ineffective in hitting targets and the damage was mostly psychological rather than physical. By 1917 the airships were being superseded by fixed-wing Gotha bombers. A shrapnel bomb dropped from one of them in the first big raid, in June of that year, hit a school in Poplar near the docks, killing eighteen of the children and causing shock and anger throughout the country.

One of the many factories that switched to producing explosives for the military was the Brunner Mond & Co. caustic soda works in the denselypopulated suburb of Silvertown, close to the Royal Docks. The company was requested by the Ministry of Munitions to produce the volatile explosive TNT, which began in September 1915. In January 1917 a fire broke out in the plant during the evening and a massive explosion occurred just before seven o’clock, which devastated not only the factory but much of the surrounding neighbourhood. Seventy-three people were killed including seven PLA staff, and ninety-four seriously injured. It would have been worse if the works had not been closed for the night. The explosion was so great that it could be heard up to 100 miles. Nearly 1,000 homes, many housing people who would have worked in or around the docks and wharves, were totally destroyed and a further 70,000 damaged. Fires broke out along the Thames-side wharves. Sheds and other buildings were damaged or destroyed in the Victoria Dock, taking up to two years to re-erect or repair. The grain silos around Pontoon Dock were particularly badly damaged. One of the two gas-holders at the East Greenwich Gas Works on the opposite side of the Thames at the Greenwich Peninsula, at that time the largest in the world, was damaged and was thereafter reduced in size. A payment of £250,000 was made by the government to the PLA for repairs. This was a time when bad news was covered up or heavily censored and the Ministry of Munitions merely issued a simple statement. The following day the local council began to organize the clearance of the damaged area and provide temporary housing for those displaced. A relief office was set up at Canning Town where residents could apply for aid and seek compensation, which eventually amounted to £3 million. It was never established as to what had caused the explosion. The resulting enquiry, which was not made public until the 1950s, criticized both the Ministry of Munitions for producing explosives in a heavily populated area and the Brunner Mond management for not keeping a round-the-clock watch for fires. The immediate area remained undeveloped for many decades and is now the site of the Thames Barrier. A stone memorial marks the location of the explosion and there is a plaque in Postman’s Park in the City in memory of a policeman who died during rescue operations.

Germany had developed submarine technology. In the first months of the war they restricted their attacks to Allied naval vessels but from October 1914 they were also intermittently targeting cargo and passenger ships. A Londonbound ship carrying food was sunk as it left Falmouth. The government therefore decided it was safer for shipments to be sent to ports on the west coast of Britain and their cargoes forwarded on to London by rail. In March 1918 it became necessary to entirely close the Straits of Dover to shipping. As the West Coast ports were generally not suited to the types and volume of cargoes, however, the policy led to congestion and food shortages during 1917–18. Ongoing improvements to London’s port facilities were put on hold from the beginning of 1916 as it became difficult to obtain suitable machinery. By 1918 the Port was handling only half the pre-war tonnage.

In May 1917 the British Workers League organized a great rally in Hyde Park in support of their comrades in the military at which one of the speakers was Ben Tillett of the Dockers’ Union. Over 400 PLA employees lost their lives serving in the war, as did an unknown number of casual dock workers and those involved in other Port-related industries.

The threat of industrial action by British merchant seamen led to the government forming the National Maritime Board in November 1917 to regulate wages and working practices. The board brought together under government control the Shipping Federation from the employers’ side and the National Union of Seamen and National Union of Ship’s Stewards from that of the employees. It was intended as only a wartime initiative but in 1919 was re-established as a permanent organization for joint consultation, without government involvement.

Ships continued to increase in size and at the beginning of the twentieth century some were too large even for the Royal Albert Dock, which was restricted to those of 12,000 tons and 500 feet in length. Prior to their demise, the East & West India Company had planned to create a new Royal dock. Plans by Frederick Palmer were completed in 1911 for a dock to the south of the Royal Albert, where the PLA owned land acquired by compulsory purchase orders obtained in an Act of 1901, and contracts placed the following year. Work slowed down during the Great War as men went off to join the services and materials became scarce.

In 1918, when the Admiralty was in need of additional dry-docking facilities, a new priority was given to the planned dock. Displaced residents were provided with 204 newly-built homes on the west side of Prince Regent’s Lane, opposite Beckton Road recreation ground. The existing road from the City to the Royal Docks was carried over the new basin by a bascule bridge. The King George V, the most modern dock in the world at that time, was finally opened by the King, accompanied by Queen Mary, in July 1921. They arrived on a steam yacht flying the white ensign that cut through a ribbon, watched by 8,000 invited guests, as well as crowds who lined the river to see them pass by. After berthing in the dock, the King and Queen disembarked to inspect the premises. As the King declared the new dock open, a gun salute was fired from the Royal Arsenal at Woolwich on the opposite bank of the river.

Six two-storey warehouses with storage space of 700,000 square feet stood along the northern quay of the George V Dock. The southern side of the dock was lined with ‘dolphin’ berths. These 520-foot-long jetties lay parallel to the main quays at a distance of thirty-two feet, allowing lighters to pass between jetty and quay. Forty-nine cranes on the dolphin berths allowed cargoes to be simultaneously discharged or loaded onto lighters on both sides of a vessel, which moored on the outside of the jetties, or onto the quayside. The dock was created with the most modern facilities of the time for loading and unloading, storage and transport, including large transit sheds with twenty-seven electric cranes of five-ton carrying capacity. Railway lines served both north and south quays as well as behind the warehouses. The cost of the project was £4,500,000.

At 64 acres the King George V was smaller than its neighbouring Royal Docks. Its length was 4,500 feet, the width varying between 500 and 700 feet, and with over 3 miles of quays, able to accommodate up to 15 of the largest ocean-going vessels of the time, of up to 35,000 tons. A passage linked it to the Royal Albert Dock. It also contained its own entrance lock onto the river at Gallions Reach of 800 feet by 100 feet, operational at all tide levels. In 1939 the Cunard liner RMS Mauretania, the largest ship to pass up the Thames, was able to enter through the lock. Harland & Wolff operated a ship-repair workshop from within the dock that could accommodate vessels up to 25,000 tons. The combined size of the three Royal Docks measured 230 acres, the world’s largest surface of impounded water, with 11 miles of quays. The George V remains the only London dock to be created as part of a public service.

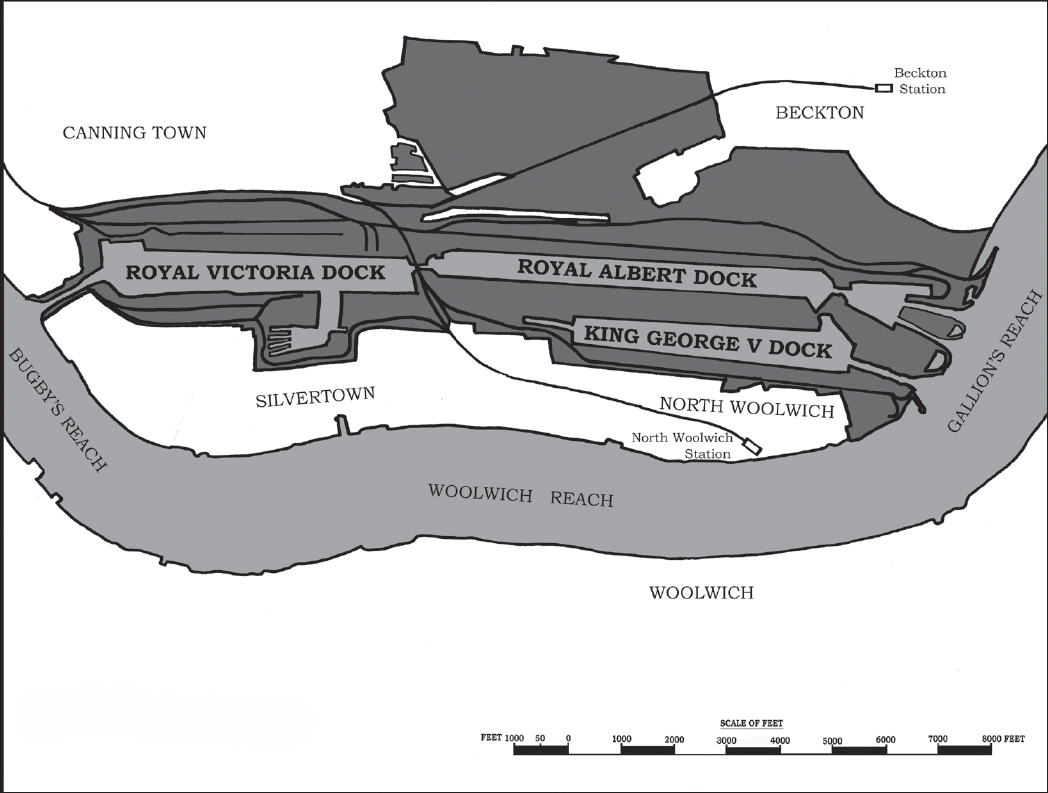

The Royal Docks after 1921.

The PLA also considered the idea of siting a larger dock on open land to the north of the Royal Albert and Lord Devonport arranged the purchase of 202 acres of land and various shops and houses. A plan was drawn up in 1919 by Cyril Kirkpatrick, successor to Palmer, but by the time the project was revisited in the early 1920s the priority had changed to Tilbury so the north dock was never built.

The Great War ended with a diminished amount of trade passing through the Port. Traffic with Germany and Russia had disappeared, as had that with Belgium and the Netherlands, this having largely been of German origin. Business soon recovered however, rising from 15 million tons in 1918 to 33 million in 1920. At the end of that decade both London and Liverpool faced competition for the entrepôt business from Hamburg, as well as Antwerp and Rotterdam, all offering substantially lower berthing and handling rates. Shipowners were also facing difficulties as too many ships competed for too little business. In response, the PLA reduced their rates and undertook an advertising campaign in order to win back business, featuring aerial photographs of the Tilbury and Royal Docks and boasting of the PLA’s expertise in handling cargoes. Lord Devonport, who had been so energetic in the early years of the PLA, retired from his position in 1925. His place was taken by Lord Ritchie of Dundee, vice-chairman under Devonport and head of a firm of East India merchants. Although not the first general manager, David Owen, appointed in 1922, was the earliest in that position to really make his mark on the development of the Port.

Between the First and Second World Wars London remained the largest manufacturing city in the United Kingdom, producing many types of general goods. Its population was growing, as was the number of visitors. As well as wharves, the Thames and its tributaries were lined with factories and power stations at which ships and lighters transferred fuel and goods. Vessels arrived in London from every country in the world and railways linked most of the docks with the metropolis and other parts of Great Britain. Continental ports such as Hamburg, Rotterdam and Antwerp were within easy reach by steamer. Finished goods were exported, although Liverpool had the advantage in that respect due to its proximity to the factories of Lancashire and Yorkshire.

The PLA’s post-war plans for modernization and upgrading had been badly delayed by the war and the only project to be initiated during that period was the new headquarters building. The three phases of Frederick Palmer’s programme of 1910 were in due course also highly modified by practicalities, the outbreak of war, and the ever-changing requirements of the Port. It was not until the second half of the 1920s and into the 1930s that further major projects were carried out by the PLA.

The intention in 1910 had been to undertake upgrading at the important West India Docks and from 1912 additional land was acquired by compulsory purchase powers. In the event, the plans were pushed back by more than a decade, finally starting in 1926. There was at least the advantage that by then the railway passenger service across the docks to North Greenwich had closed, so it was possible to considerably extend the original scheme. A new entrance lock to the South West India Dock was created; 80 feet in width, 955 feet in length and 35 feet deep, opening in August 1929. At the same time a new impounding station, built across what had been the old entrance to the former City Canal, raised the water level. Thus, larger ships with deeper draughts could enter. Wide passages were created between all the West India and Millwall Docks and new berths were provided with modern transit sheds.

Prior to the Great War a 1,000-foot-long, 50-foot-wide jetty was planned on the river at the Tilbury Docks. This would allow a fast turnaround for vessels that were only loading or unloading part of their cargo, without the lengthy time taken to lock in and out of the docks. A contract for the construction was agreed in 1912 but work was slow during the war and in 1918 the original contractors were released from their obligations. It was finally completed using PLA direct labour. Cranes were ordered in 1920 and the jetty opened in 1921. The original plan was to eventually double its length but the jetty proved unpopular, particularly with barge-owners due to the river current and tidal fall, and the extension never took place.

Unlike Lord Devonport, Lord Ritchie felt the need to invest downriver. By the 1920s ships were becoming larger and there was concern that those heading for the Royal Docks would cause congestion on the river. Also, the war had stimulated the use of motor vehicles and, by then, ex-military trucks were being sold off cheaply, becoming widely available for commercial use. Tilbury thus became a more attractive option for investment. A project for a larger entrance lock of 110 feet wide began in 1926, as well as a new dry dock, both completed in 1929.

In 1926 a South American meat berth was constructed at Tidal Basin in the Royal Victoria Dock. Three cold stores were capable of holding over 500,000 carcasses, along with all the equipment and staff required to process meat. From there the PLA’s insulated railway wagons could transport the frozen meat to their stores at Smithfield market. The PLA had a combined cold-air storage of 11,000 tons. Bananas from Jamaica were a specialty at the Royal Albert, with a mechanized berth capable of unloading more than 80,000 stems each day. The first shipment arrived on board the Jamaican Producer in 1929. Three flour mills were constructed on the south side of the Royal Victoria Dock. The original jetties along the north side of the Royal Victoria were becoming an inconvenience and were removed, with new false quays constructed. Three quarters of a mile of linear quay and floating pneumatic grain elevators, discharging directly from ships into vast silos, were installed. New berths were added on the north side at what was known as the ‘mudfield’ and five new sheds built. The width of North Quay at the Royal Albert Dock was increased. The Connaught Passage that linked the Royal Victoria and Royal Albert Docks was deepened, a difficult and costly exercise due to the railway tunnel below. In 1934 the Ministry of Transport’s two-mile Silvertown Way approach road to the Royal Docks was opened.

Some of the 7 million tons of grain that arrived in the Port annually was also being directed to the Surrey Commercial Docks where there were seven granaries. The three central ponds at Rotherhithe were converted into the deep-water Quebec Dock, which opened in 1926, with six timber-discharging berths. That brought the Surrey Docks up to 11 docks, 136 acres of water area, including 70 acres of ponds for floating timber, 9 miles of quays, 64 acres of open storage and 58 acres of storage sheds. Further improvements continued to be made at Rotherhithe and the Surrey Commercial Docks were the world’s largest timber yard by the start of the Second World War. The St Katharine and London Docks, where new modern buildings were constructed, remained busy between the wars, although by then only with very small ships and lighters.

London continued to be the pre-eminent port for the importation and sales of both wool from Australia and tea from India, having the infrastructure and expertise lacking elsewhere. The amount of PLA warehousing at the docks and in the City was vast. In the mid-1920s they could hold one million bales of wool, 28,000 pipes of wine, 120,000 casks of brandy, 330,000 puncheons of rum, 125,000 tons of grain, 50,000 carcasses of meat, 35,000 tons of tobacco, 30,000 tons of tea and one million tons of other goods. There were acres of sheds at the Surrey Commercial Docks to store timber arriving from the Baltic and Canada. Millwall handled two-fifths of London’s grain imports in the early part of the century. Wool was kept at the London Docks and wines, ports and sherries in their vaults. Sugar and rum continued to arrive at the West India Docks as they had done since their beginnings. Exotic and valuable goods such as spices, ivory, silks and oriental carpets, as well as tea, were stored at the former East India warehouses in the City at Cutler Street, Houndsditch, and at St Katharine’s. Tobacco went to the north side of the Royal Victoria Dock and frozen meat to the Royal Albert Dock. Large quantities of fruit, butter, cheese, bacon and grain such as wheat, corn, oats, maize and barley arrived from overseas. A relatively new importation was cultivated plantation rubber. During and after the war motor transport had replaced horse-drawn vehicles and required a constant supply of fuel; Lord Ritchie therefore valued the petroleum trade. New terminals were opened at Thurrock and Canvey Island, with Esso at Purfleet becoming the PLA’s largest customer. An important new development was when the Ford Motor Company built their factory and wharf at Dagenham in 1929.

The principle domestic and industrial fuel used in London was coal that arrived by sea from the North-East or South Wales. Much of it was brought into the Port on a fleet of colliers owned by independent companies. There were also a number of riverside coal-burning gas and electricity stations that operated their own fleet of colliers. In many cases their seagoing ships were designed to pass under London’s bridges and these were known as ‘flatirons’. An average of 13 million tons of seaborne coal arrived in London each year yet in 1936 petroleum imports overtook coal for the first time.

The river was busy with passenger steamers in the second half of the nineteenth century. In the first half of the twentieth century excursions from London to Gravesend, Southend and Margate remained popular during the summer months. The interwar years were the peak period of ocean-going liners. London had previously been a popular embarkation and disembarkation point but Liverpool and Southampton had taken a far greater share of that business, particularly to North America and France. Nevertheless, Tilbury was used by liners operating to and from India and the colonies and by ships that carried both passengers and cargo. The PLA were keen to develop services but shipowners were complaining about the time it took for travellers to disembark. Passengers had to be brought ashore on small boats, so even before the war Lord Devonport had considered a landing stage important. To open one required negotiation with the Midland Railway, owners of the Tilbury Riverside Station, which made slow progress. Agreement was finally reached in May 1919 but even then work did not begin until 1928. The landing stage, designed by the PLA’s architect Sir Edwin Cooper, projecting 370 feet into the river and designed to rise and fall with the tide, was 1,142 feet long. A twostorey building was constructed to house a baggage hall, waiting area, customs and immigration facilities. The passenger terminal was opened in 1930 by Prime Minister Ramsay MacDonald. It became famous as a departure point for those emigrating to Australia and other Commonwealth countries and was used by ships bringing immigrants from the West Indies during the 1950s.

Dredging ceased altogether in October 1915 but resumed again after the war. Depths and channel widths had been fixed, varying from 30 feet depth and 1,000 feet of channel at Crayfordness to 14 feet depth and 450 feet of channel at London Bridge. New plant was acquired to undertake the work, including four dredgers. By 1921 over 1,500,000 cubic yards was being raised each year, rising to 4 million cubic yards in 1925. The giant, self-propelled steam-powered floating crane the London Mammoth, weighing 1,000 tons and rising 67 metres above the waterline, began operation in 1926. It could originally lift 150 tons, increased to 200 tons in the 1960s. It was in use at the Port until 1975 and its replacement of the same name is still in service.

A failure of the former dock companies, in which the PLA was to succeed, was that of better integrating the docks with the national rail network. In the 1930s the PLA had 140 miles of track, 40 locomotives and ran 120 trainloads per day. There were sidings at the Royal Docks, Tilbury, West India and Millwall. Rail played a key part before the Second World War but declined in favour of road transport thereafter.

During the nine-day national Great Strike of May 1926 each of the docks was blockaded by pickets. Supplies of flour for the south of England up to the Midlands were about to run out within the first week, while loaded ships in the docks were lying idle. The government therefore set up a base in Hyde Park and on the third day a convoy of 105 lorries manned by Grenadier Guards set out from there to surround and secure the Victoria Dock. Once the guards had accomplished their task, 150 volunteers embarked on a lighter at Westminster Pier and were towed down to the dock. There they loaded lorries with sacks of flour that returned back to Hyde Park. This was repeated several times but it was not providing sufficient supply. The government therefore made an agreement with the Admiralty to operate lighters on the river flying the naval white ensign, carrying flour from the docks to where it could be safely discharged. In that way 17,000 tons of foodstuffs were removed from the docks in 48 hours.

The government was also concerned that the electricity supply from a Labour-controlled power station to the King George V Dock would be cut off. Three-quarters of a million carcasses of meat were stored at the dock and without refrigeration Londoners and many in the south of England would eventually go hungry. Two days before the supply was duly cut, two Navy submarines quietly crept into the dock and were able to connect to the dock’s circuits from their on-board generators.

The USA was experiencing an economic boom during the first half of the 1920s and the amount of American trade passing through the Port of London increased accordingly. That came to a spectacular end in October 1929 when the Wall Street stock market crashed, temporarily diminishing the US economy during the early 1930s. Luxury exports destined for the US market were particularly adversely affected. Stock market investors, attempting to cut their losses, sold shares in European businesses causing financial problems for public companies associated with shipping and the Port. Pay was cut for British merchant seamen. With a surplus of available manpower the casual labour system continued, despite continued calls for its abolition. To alleviate hardship, a new method was introduced whereby workers of all types and skills were ‘stood-off ’ on a rotation basis. Each dock was allocated its quota of workers daily according to the amount of work available.

During the nineteenth century heavy industries that involved iron and steel moved away from London to those areas where the raw materials were more easily accessible. Boat-building, repair and the manufacturing of marine equipment returned to the Thames when, between 1924 and 1972, the Belfast shipbuilders Harland & Wolff operated a major yard at North Woolwich, adjacent to the lock entrance to the King George V Dock. The works were noted for the building of the ‘Woolwich’ class of canal narrowboats for the Grand Union Canal Carrying Company.

London’s many tugs were all steam driven until after the Second World War. Around 7,000 barges and lighters, owned by some 200 companies, were operating on the river, ranging from 50- to 500-ton craft. Many were designed for specific trades, such as oil or meat. When not being towed, they were manoeuvred by means of thirty-foot oars known as ‘sweeps’. These craft were operated by skilled lightermen, work that was often passed down from generation to generation in the same family. Prior to the Second World War, flat-bottomed Thames spritsail barges were still operating, perhaps the last cargo-carrying sailing vessels on the river.

By 1931 the tonnage carried on British ships remained at about the same level as in 1919. Other nations were subsidizing their shipping lines. At the same time, unsubsidized British tramp ships – small vessels usually owned by private companies and which made up a sizable portion of the British fleet – were being laid up for want of cargoes, so the government introduced its own subsidies between 1935 and 1938. Nevertheless, the percentage of world tonnage carried on British ships decreased between the wars at the expense of those from the USA, Germany and Japan. In part that was because British merchant ships continued to rely on slower coal-burning engines, whereas new vessels of other nations were being fitted with faster and more competitive diesel-powered engines.

Mechanization and the Great Depression of the early 1930s reduced the number of people working in the Port from 52,000 in 1920 to 34,000 in the latter 1930s. The greatest degree of cooperation and harmony between workers and management was achieved in the 1930s. The surplus of labour at that time probably made it worthless to strike for better pay or conditions and joint committees made discussion and compromise easier. There were nevertheless numerous minor and local disputes.

A serious fire broke out in 1933 in the vaults of the old warehouses at the North Quay of the West India Import Dock where 6,500 casks of rum were being stored. To extinguish it took 65 pumps, 3 tugboats, and 378 firefighters 63 hours. Several warehouses were burned down and never rebuilt and over 3 million litres of rum destroyed.

By the 1930s the Port of London, after more than a century of expansion and with the world’s largest man-made enclosed dock system, had reached the end of its growth, the maximum size it would ever achieve. An estimated 1,500 wharves, jetties and yards lined the river between Brentford and Gravesend. Every port in the world was served, either directly or by trans-shipment and the Port was more complex than it would ever be again in the future. The combined docks and wharves were the nation’s principal storage centre for goods of many varieties. Around 100,000 men were dependent, either directly or indirectly, for employment. In 1938 thirty-eight per cent of the UK’s trade passed through London, an all-time high that was never to be achieved again, with 63 million tons carried. During that period 50,000 ocean-going ships arrived each year, coasters were making 15,000 round trips, 250 tugs worked on the river, as did 10,000 lighters and 1,000 sailing barges. Three hundred thousand passengers arrived or departed annually. Larger ships primarily used the enclosed docks while coastal and Continental trade operated from riverside wharves. Twenty-eight graving docks operated for repairing ships. In the following forty years the world would go through dramatic changes however, as would the methods by which the world moved its goods.

After the Great War, ports around the country attempted to create registers of dockers in order to regulate employment and the call-on, with the task organized by local committees. It proved to be unworkable. It was estimated that 34,000 men worked in the Port of London yet 62,000 came forward to register. One of those managing the registration on the London committee was Ernest Bevin who already had some success creating such a register at his home port of Bristol and Avonmouth. Despite the failure of the scheme, for the next two decades and more Bevin pursued his ideal of reforms of the port labour system and the end of casual working.

As the Port returned to normal and trade was brisk after the Great War, the National Transport Workers’ Federation again took advantage of the strength of business, demanding a minimum wage for its members of sixteen shillings a day for a 44-hour week. The employers proposed a public enquiry to consider the matter. It was duly arranged by the government under the chairmanship of the Law Lord, Lord Shaw of Dunfermline. An expert in industrial legal cases, Sir Lynden Macassey KC, represented the employers and Ernest Bevin represented the workers.

Bevin’s masterful opening speech lasted eleven hours, given over two and a half days. He claimed that a docker needed £6 each week to maintain a family of five. Macassey responded that was an exaggeration and called witnesses to testify to that effect. Sir Alfred Booth, chairman of the Cunard line, stated that a Liverpool docker could adequately manage on three pounds four shillings and tuppence. Professor of statistics at London University A.L. Bowley was asked to give his opinion and he responded that three pounds and seventeen shillings was enough. To resolve the point, Bevin and his secretary travelled to Canning Town and there purchased the amount of food that would be available each day on those levels of pay. They took their purchases to the union offices, cooked it, divided it onto five plates and presented the results to the enquiry. Bevin asked the court their opinion as to whether the small portions they saw before them were enough to feed a man who was asked to carry seventy-one tons of wheat every day. The court accepted the argument and the dockers received their minimum of sixteen shillings per day.

To celebrate, the workers marched from Temple station to the Royal Albert Hall where a rally was held in Bevin’s honour. Yet again, it was a short-term gain. The post-war boom ended in the 1920s and wages fell back to ten shillings per day. Poverty around the docks was severe in the decade from 1921. In 1923 the employers proposed a reduction from eight shillings to five shillings and sixpence for the four-hour minimum period. The dockers responded by going out on strike for eight weeks until forced to return.

As a result of the public enquiry of 1919, the employers formed the National Council of Port Employers, headed by Devonport, which was able to represent their interests in labour disputes. Bevin was instrumental in amalgamating fourteen unions to become the Transport & General Workers Union in 1922, for which he became its first General Secretary, with the former lighterman Harry Gosling as its president. There was not full unity between workers in the port however, and the T&GWU continued to have a rival. Stevedores had been represented since the nineteenth century by the Amalgamated Stevedores’ Union, which enjoyed a close relationship between its officers and members. They could not be persuaded to join the T&GWU and at that time changed their name to the National Amalgamated Stevedores, Lightermen, Watermen & Dockers’ Union. Those who belonged to the T&GWU were henceforth known as ‘whites’ and NASLW&DU members as ‘blues’, each based on the colour of their membership card. Rivalry and disunity between the two unions continued until the closure of the docks in the latter twentieth century, with the T&GWU often losing members to the NASLW&DU.

Bevin played a leading role when the Port workers supported the General Strike of May 1926, which closed the Port. When the strike ended, Bevin was forced to sign an agreement admitting that the workers had broken previous agreements but nevertheless arranged for all the Port strikers to be reinstated on their previous terms.

When Winston Churchill was appointed Prime Minister in 1940 he formed a wartime emergency coalition National Government with representatives from all the major parties. Despite their differences of political opinion, he had been impressed by Bevin’s work ethic and his opposition to both fascism and the pacifist element of the union movement and invited him to join the coalition cabinet as Minister of Labour. It was unusual in that Bevin was still General Secretary of the T&GW Union at the time and not actually a Member of Parliament. To overcome the anomaly Churchill arranged for Bevin to stand as Parliamentary candidate for the London constituency of Wandsworth Central. The other parties agreed that he could take the seat unopposed. Despite the war, Bevin took the opportunity to introduce a number of reforms in favour of British workers. Upon the defeat of Germany, Bevin joined Churchill for the VE Day celebrations in London. By then he had drawn up plans for the demobilization of the forces and their return into the civilian workforce.

After the war, normal party politics resumed and the Labour Party won the 1945 General Election. The new Prime Minister, Clement Attlee, appointed Bevin as Foreign Secretary and for the next few years he played a key role in international affairs including the formation of NATO, the United Nations and the State of Israel. There was a story amongst dockers that in 1947 a group of them discovered a hamper from an overseas government addressed to Bevin. Cold and hungry they consumed the contents, repacked it and sent it on with a card wishing him a Happy Christmas.

Following the declaration of war against Germany and its allies, on 3 September 1939 all UK ports were put under the control of Port Emergency Committees, responsible to the Ministry of Transport. The committee for the Port of London was headed by J.D. (later Sir Douglas) Ritchie, who had succeeded David Owen as general manager of the PLA in 1938. The Admiralty also created a Naval base for the Port of London, with its flag officer and staff based at the PLA headquarters, the control centre for the Port throughout the war.

Adolf Hitler was well aware that to cripple the Port of London was to weaken Britain’s ability to survive and, as it was an entrepôt port, would furthermore affect the entire British Empire. Prior to the war, the Luftwaffe had been flying reconnaissance flights over London, taking aerial photographs, and had marked key points along the river as targets. For centuries the winding river and dangerous estuary shoals had long protected the Port. It was clear from contemporary conflicts in Spain, China and Abyssinia, however, that aerial attack would be inevitable if war occurred. Distinctive from the air both during the day and by moonlight it was an easy target for airborne bombers. Spread along sixty-nine miles of tideway, the Port was extremely difficult to defend. The following years were to become some of the most dramatic and challenging in the long history of the Port of London.

The PLA had some time earlier developed a defensive plan at the government’s request that was adopted for all ports. A River Emergency Service had been formed, able to aid and advise the Navy with local expertise. Thames lightermen and barge-owners formed the Lighterage Emergency Executive (later superseded by the London Tug & Barge Control), making themselves available to the Port Emergency Committee. Shelters were provided for workers, pillboxes constructed, first-aid stations established and some buildings strengthened. Steel pylons were erected as lookout posts. A wartime nerve centre was created at the PLA headquarters although aspects of its work moved to a safer location at Thames Ditton. Naval ships were stationed at the sea entry to the Thames. From September 1941 they were replaced by Maunsell Sea Forts, constructed in the Surrey Docks and towed downriver from there. Gun batteries were installed on each bank of the lower river. Locks and other key points were guarded by military police. The Navy requisitioned a number of Thames tugs to act as guardships, forming the Thames & Medway Examination Service, with several based at the Naval Control Centre at Southend. Conscription into the forces began in April 1939 but Port workers were included on the Schedule of Reserved Occupations and were thus exempt.

There was an initial period known as the ‘phony war’ when the British people prepared themselves for the worst. Women and children were evacuated to the countryside, leaving Port workers separated from their families. Yet during the first year there was no significant harm done to London and some of those evacuated drifted back to their homes. During that period more than 6,000 port workers were trained in various aspects of defence.

By the end of 1939 magnetic mines were being dropped into the Thames Estuary by German aircraft, sinking a number of merchant vessels. Each morning thereafter minesweepers left Gravesend and Sheerness to clear the shipping channels. It took several months for the Navy to introduce the ‘degaussing’ method that neutralized a ship’s magnetism and thus made them resistant to the devices. In the meantime, the PLA’s jurisdiction for the salvaging of ships was extended to a greater area. Groups of dockers were formed into units of the Royal Engineers, of which there were twelve by the end of the war, and they assisted in the British Expeditionary Force mission in September 1939 and their retreat in 1940. Operations took place in coastal areas as far as the Arctic Circle, North Africa and Burma.

From the summer of 1940 Germany took occupation of the Netherlands, Belgium and France and for the following four years their forces were only a short distance from shipping entering and leaving the Estuary. Allied troops were suddenly forced to depart for the Continent and ‘Operation Dynamo’ was launched to undertake the evacuation. A bizarre fleet of small vessels of all shapes and sizes, some having not been designed to go out to sea, were assembled to rescue troops from the beaches of Dunkirk, including thirty Thames tugs. Much of the fleet was assembled, provisioned and crewed at Tilbury Docks. Some, including at least eight Thames sailing barges, failed to return. At that time a German invasion seemed inevitable and two booms were laid across the Estuary, the outer one from Shoeburyness in Essex to Minster in Kent and the inner boom from Canvey Island to St Mary’s Bay. Gaps were kept open during the day, guarded by the Navy, but they were closed at night. Merchant ships began sailing in convoys, which assembled at the Naval Control Service station at Southend Pier. Shipmasters received their orders in the pier’s dance hall.

Scattered German air raids started to take place along the east coast. For London, the phony war ended in late August 1940 with a raid on north and east London followed by another on the City the next day. In the following year air-raid sirens were a familiar sound to Londoners and gave warning to take shelter. A bomb partially destroyed a boatyard at Tilbury on 1 September. The Estuary fuel depot of Thameshaven was targeted by German bomber planes on 5 September, creating a conflagration that burnt for several days and could be seen far out to sea. Then, at around 5pm on the sunny Saturday afternoon of 7 September 1940, 348 bombers, supported by 617 fighter planes, flew in perfect formation along the Thames, with the Port as the main target. Warehouses, docks, factories and homes between Woolwich and Tower Bridge were immediately destroyed by high explosives or set alight by incendiary bombs. Most areas of the Port suffered, as well as Woolwich Arsenal and Beckton Gasworks. Timber at the Surrey Commercial Docks began to burn, as it did at the West India and Royal Victoria Docks. A bomb hit the entrance lock of the King George V Dock as a ship was passing through. Fires burnt at the great flour mills at the Royal Victoria Docks. Several ships took hits in the West India and Royal Victoria Docks. Firefighters were so occupied with major blazes that smaller ones had to be left to burn themselves out. Damage throughout the Port was so great that some buildings were subsequently demolished and left as open ground for decades. Huge clouds blackened the sky as warehouses full of inflammable goods and nearby houses were set alight. Sixty craft were sunk or destroyed and blazing barges set adrift floated down the river.

Incendiaries were perhaps a bigger threat to the Port than high explosive bombs. Fires were still burning from the afternoon raid when, shortly after sunset, the next wave of bombers arrived, with enemy aircraft guided by the light of the flames. The Surrey Commercial Docks, still lit by burning timber from the earlier raids, suffered most severely during the first weekend. Fortytwo major fires took place, spread over 250 acres, along three miles of the south bank of the river. They were tackled by firefighters from as far as Bristol and Rugby. Containers of fuel oil, dropped from aircraft, as well as delayedaction bombs and years of accumulated woodchips, ensured the continuation of the conflagration for several days. Daylight revealed a landscape of gutted warehouses, sunken ships and human bodies. Rum barrels exploded in the Royal Docks; and paint, pepper and flour burned in various docks and wharves. Burning rubber was particularly difficult to tackle. The heat was so intense that paint blistered and peeled on vessels moored some distance away. The Woolwich ferry worked all night to evacuate residents of Silvertown and their belongings. In the first night alone 430 civilians died in London including a number of dock workers. In the first 12 hours 120 major incidents were reported in the Port, with over 60 craft sunk or destroyed.

Bombs inevitably failed to hit their intended targets and hit others. For example, on that first afternoon many of the residences in Stebondale Street in Cubitt Town, at the southern end of the Isle of Dogs, were destroyed. Yet the bombers failed to put out of action the anti-aircraft battery at nearby Mudchute and almost all the nearby wharves were left untouched. The residential area north of Mudchute, between Manchester Road and the Millwall Inner Dock, was devastated during the course of the war, whereas the adjacent Millwall Docks were left relatively unscathed.

One hundred and seventy one bombers returned for nine and a half hours the following night, leaving 400 dead and more destruction. The basins of the St Katharine Docks became a cauldron of flames when a fire in E Warehouse spread to others filled with flammable goods. Burning coconut oil and paraffin wax spread out across the water, blazing for several days and laying waste to some of the warehouses. The Rum Quay at Millwall docks burned out, destroying one and a quarter million gallons of the spirit. The dockmaster and his assistants worked continuously for forty-eight hours to move imperilled barges as blazing rum flowed across the water, puncheons exploded and fiery rivers of glutinous sugar crept from burning warehouses. The PLA headquarters on Tower Hill took a direct hit that night, completely destroying the central rotunda and causing extensive damage to other parts of the building. Incredibly there were no major injuries and staff within the building continued their work. The bombers returned again and again, every night for seventy-six nights, except on one when there was bad weather, until mid-May 1941 when a final 500-bomber onslaught was unleashed on the capital.

In the first few days, Anti-Aircraft Command were ill prepared. Guns had mainly been located at downriver sites. Within a week warning systems, communications, searchlights and anti-aircraft guns were relocated to suitable places, as well as mobile guns mounted onto lorries. Those measures ensured that bombers had to fly at greater altitudes with subsequent lack of accuracy. Barrage balloons could be raised to a height of almost a mile and their steel mounting cables acted as a deterrent to enemy pilots. On Sunday, 15 September alone, fifty-six Luftwaffe bombers were brought down by RAF fighters. As well as high explosive bombs, incendiaries and oil bombs, the enemy also dropped time bombs that unexpectedly exploded later, plus parachute bombs that detonated above roof level and thus caused a wider area of destruction.

As damage occurred to roads and bridges, some riverside communities around the docks became cut off from neighbouring districts. After the first week the Isle of Dogs was looking quite derelict and many residents had moved away. By mid-September the dock bridges had been withdrawn for protection and the foot tunnel to Greenwich closed due to bomb damage, making it very difficult to leave the Island. Residents of Wapping were evacuated on a flotilla of boats and a similar evacuation took place at the LCC Hospital at Rotherhithe. Some brave souls remained even after being bombed out of their homes several times. Despite the destruction around them, and in some cases the loss of their homes, workers continued to keep the Port operating.

There were many tragic stories. One took place at Bullivant’s Wharf rope and wire factory at Millwall on the Isle of Dogs in March 1941. With specially reinforced concrete floors to support heavy machinery, it appeared to be particularly safe and was thus used as a public night-shelter during bombing raids. Sadly, when the building was hit, the heavy floors collapsed, killing around 40 and injuring a further 40 people sheltering below.

The coming and going of vessels still had to continue according to the tides, despite the bombing raids. A blackout was imposed at night so navigation and dockside work was required to be undertaken in darkness. Many regular tasks, such as pulling a tail of laden barges under Thames bridges or passing a ship through a lock, became extremely difficult and dangerous when undertaken in complete darkness. Despite the great damage being inflicted, a diminished staff and the need to continue its normal operations, PLA staff also took on the civil defence of the docks and river. That included the provision of firstaid stations, firefighting, salvage and wreck-raising. Along the length of the tidal river volunteers kept watch each night, reporting anything falling into the water to the Flag Officer In Charge at the PLA headquarters, from where mine-sweeping and clearance activities were coordinated. Ordinary dock workers extinguished incendiary bombs, which often fell in awkward places such as on roofs, in order to protect the contents of warehouses. Fires that took hold in private wharves, often in cramped conditions and with limited staff, were particularly difficult to extinguish. Tugs and lighters continued their journeys during raids, their crews often kicking incendiary bombs overboard. Most Thames tugs, operating as the River Tug Fire Patrol, were equipped with powerful pumps that could be used for firefighting. Between 1940 and 1950 the PLA had to deal with eight shipwrecks caused by the conflict and raise 35 ships and 600 small craft from the river. Staff kept the port operational despite the difficult and dangerous conditions, although trade had been reduced to a quarter of its pre-war levels.

From early 1941 the enemy began dropping parachute magnetic bombs as far upstream as Hammersmith. These could lie dormant on the bed of the river or dock until triggered by a passing vessel. A dramatic example occurred in April 1941 when the oil tanker Lunula, having arrived at Thameshaven from Halifax in Canada, detonated a mine dropped the previous night. The resulting fire blazed for ninety-seven hours.

As the war progressed the authorities became more prepared, with air-raid early-warning and anti-aircraft guns in place and better defence provided by the Royal Air Force. Despite the constant destruction, the Port somehow managed to continue operating, although at a reduced level. The river had to be closed on some occasions to sweep for mines. With diminishing returns, and other fronts on which to fight, the Germans had largely given up their efforts to destroy the Port by the middle of 1941. From the second half of April the Luftwaffe instead concentrated on other British ports such as Belfast, Plymouth, Portsmouth, Merseyside, Tyneside and Glasgow. Despite the respite from bombing, the Port remained under a state of siege as the enemy continued dropping mines and maintaining U-Boat operations in the approaches. In June 1941 Winston Churchill reported in a secret session of the House of Commons: ‘The Port of London has now been reduced to one-quarter … and the English Channel, like the North Sea, is under close air attack of the enemy.’

Patterns within the Port dramatically changed. Some ships familiar in London were requisitioned by the Navy. Others that worked particular trades became general carriers and berthed in different docks than previously. Unfamiliar ships arrived in London. Most long-distance trade was diverted to less vulnerable ports such as the Clyde, to where some London port staff, sea-pilots, equipment such as cranes, locomotives, tugs, lighters and a floating crane, had been transferred. From there London’s imported food supplies arrived by rail or coaster into storage facilities at the Royal and West India Docks. Reserve buffer depots were organized in safe places around the country. An exception was flour, which had to be kept within easy reach but in safe places. The solution was to store it on barges that were dispersed along the river between Teddington and the Pool. Most cargo was carried by smaller coasters, which were less vulnerable to attack than larger vessels. During the course of the war a million tons of rubble from demolished homes and factories was sent around the coast, much of it on sailing barges, to be used as hardcore for the construction of airfields on the east coast. There was an acute shortage of young workers as they were diverted to other ports or into the services. Those who remained were nearly all over fifty years of age.

It remained necessary for colliers to continue supplying London’s Thamesside power and bunkering stations with coal. During the course of the conflict there were many losses as they travelled back and forth around the coast. They were constantly threatened by submarines, E-boats and mines. Although immune from magnetic mines, wooden-hulled Thames sailing barges, which were unable to travel in convoy, were a sitting duck for enemy aircraft and only a small number survived the conflict.

At the outset, twenty Thames ship-repair yards came under Naval control in order that priorities could be set. For several years London once again became Britain’s main ship-repair port, handling over 23,000 vessels. Yards installed armaments, adapted craft for wartime duties and repaired damaged vessels. Work continued uninterrupted throughout the war, despite a number of direct hits on the yards.

W.S. Morrison, Minister of Food, pointed out that the transportation of food by ship was putting the lives of seamen at unnecessary risk. Lessons had been learnt from the Great War and the navy organized escorted convoys from the start of the conflict. Nevertheless, there was a great loss of shipping and lives from enemy action, particularly from German and Italian submarines. Over 2,700 British merchant navy ships, or the equivalent of over fifty per cent of British merchant navy tonnage at the start of the war, was sunk during the course of the conflict, with the loss of over 30,000 lives. Many of the total of over 1,350 Royal Navy ships that were sunk were on escort duty.