Figure 1: Price Ceiling

The allocation of scarce resources can be largely influenced by the system of government in a country or region. This section provides a brief thumbnail of three forms of government and the prominent decision-making mechanisms they entail.

Communism is a system in which the government owns all the resources in society and answers the three economic questions: what, how, and for whom goods are produced. Communism is designed to minimize imbalance in wealth via the collective ownership of property. Legislators from a single political party—the communist party—divide the available wealth for equal advantage among citizens. The problems with communism include a lack of incentives for extra effort, risk taking, and innovation. The critical role of the central government in allocating resources and setting production levels makes this system particularly vulnerable to corruption.

Socialism is a system in which the government maintains control of sectors of the economy that are particularly prone to market failure, such as energy, education, or health care. Socialism shares with communism the goal of fair distribution and the pitfall of inadequate incentives. Rather than the government controlling wages as under a communist system, wages are determined by negotiations between trade unions and managers. Another difference between socialism and communism is that under socialism, a single political party does not rule the economy.

Capitalism is a system in which individuals and private firms own the resources in society and answer the three economic questions: what, how, and for whom goods are produced. Under a capitalist system, private individuals control the factors of production and operate them in the pursuit of profit. Wages are determined by negotiations between managers and employees or their unions. The market forces of supply and demand largely determine the allocation of scarce resources. Government may regulate businesses and provide tax-supported social benefits. The previous sections describe how product markets can determine prices and quantities for goods and services, and this section describes the influence of various government policies.

This section studies three basic steps governments can take to manage their economies: a price ceiling, a price floor, and a tax.

A price ceiling is an artificial cap on the price of a good. Examples include rent controls in many U.S. cities and limits on the price of bread in some parts of Europe. In order for a price ceiling to have any effect, the ceiling must be below the equilibrium price as in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Price Ceiling

If the equilibrium price for textbooks was $80 and a price ceiling of $100 was imposed, it would have no effect because the price would not be that high anyway. A price ceiling of $50, however, means that 76 would be demanded and 64 would be supplied, resulting in a shortage of 12 textbooks.

Although price ceilings provide lower prices for those who are able to purchase the good, negative repercussions are common. To purchase the good, buyers may need to wait in line for long periods of time. Because the price of Duke basketball tickets is below the equilibrium price (perhaps due to a self-imposed price ceiling), students wait in line for as long as a week to purchase tickets to individual games. The time they lose waiting in line constitutes a queuing cost and would be unnecessary if the price were able to reach equilibrium where the number of buyers equaled the number of tickets available at that price.

Price ceilings can also result in black market activity. Again looking at Figure 1, because the potential buyers of the 65th and subsequent textbooks value them at close to $100 and the seller(s) could provide them for just over $50, there is an opportunity for mutually beneficial but illegal transactions, called black market transactions. For example, if the 65th book was sold illegally for $80 by a seller with a marginal cost of $55 to a buyer who values it at $99, the seller nets $25 and the buyer would get $19 worth of value in excess of what she paid for the textbook. (This assumes they do not get caught.) There are black markets for such goods as tickets to sporting events and concerts, foreign currencies that have a fixed official price (exchange rate), and human organs.

A price floor is an artificially imposed minimum price. Since 1938, the government has placed such a floor on the price of labor—the minimum wage. In order to have any effect, a price floor must be above the equilibrium price as in Figure 2.

Figure 2: Price Floor

A minimum wage of $2 per hour would be meaningless because even without any intervention, the higher equilibrium wage of $4 would be attained. With a minimum wage of $6 per hour, 200 workers will be supplied, 50 will be demanded, and a surplus of 150 will be unemployed. Notice that this is more than the 100 workers (Qe – Q1) that would be employed at $4 but not at $6. The other 50 are from new entrants into the workforce who did not want to work for $4 an hour but do want to work for $6. Clearly the minimum wage helps the 50 workers who are still employed at the higher wage, but hurts those who lost their jobs due to the decreased quantity of labor demanded at $6 an hour.

Let’s examine how a tax on a consumer good interplays with the concepts of supply, demand, elasticity, and surplus. Consider the effect of a tax on the use of hotel rooms. Fictional demand and supply curves for hotel rooms are illustrated in Figure 3.

Figure 3

In the absence of a tax, supply is S1, demand is D1, and the equilibrium price is $75 per night. Now suppose that a city tax of $10 per night is imposed on hotel guests. The original demand curve (D1) indicates the quantity of hotel rooms that will be demanded at a given price. Because consumers now have to pay $10 per room to the city, the amount they are willing to pay the hotels goes down by $10 per room, so the demand curve shifts down. The dotted line indicates the new demand curve (DT) facing hotels, and the new equilibrium is at a price of $71 and a quantity of 94 rooms. Of course, the total amount that consumers pay is $71 plus the $10 tax, or $81.

It is important to note that the total payment by the consumers has gone up by only $6—less than the amount of the tax. The amount received by the hotels has gone down by the other $4 of the tax. Thus, the burden of the tax does not depend on who has to pay for it. Rather, it depends on the relative elasticities of supply and demand. If you illustrate this same story with a perfectly inelastic (vertical) supply curve, you will find that the entire burden of the tax would be paid by hotels. That is, the total payment by consumers will be $75 per room just as before the tax, and hotels will receive only $65 per room.

In Figure 3, consumer surplus and producer surplus before the tax are represented by the areas acg and gce, respectively. The shaded area hbdf represents the tax revenue of $10 × 94 rooms = $940, which is carved partially out of the pre-tax consumer surplus and partially out of the pre-tax producer surplus. The areas abh and fde represent the post-tax consumer and producer surpluses, respectively. Notice that the post-tax consumer surplus goes all the way up to the original demand curve (D1). This is because D1 still indicates the most that consumers would pay for various numbers of hotel rooms. DT illustrates what the consumers would pay minus the portion of that payment that must go to the city.

The area bcd is called the deadweight loss, the efficiency loss, and the excess burden of the tax, because it represents the loss to former consumer and producer surplus in excess of the total revenue of the tax. That is, deadweight loss ultimately stems from the fact that fewer hotel rooms are consumed now than before a tax was imposed. In other words, every portion of the pre-tax consumer and producer surplus either remains as surplus or is captured as tax revenues except that triangle, which is lost to everyone. With experimentation you will find that, like the distribution of the tax burden, the size of the deadweight loss is also determined by the elasticity of the supply and demand curves.

Tax burden can be a difficult topic for many students. Keep in mind that a tax creates a gap (or a wedge) between what consumers pay and what firms receive. The amount of the gap is exactly equal to the tax. Note that the new price paid minus the original equilibrium price (before the tax) is the consumer tax burden. The original equilibrium price (before the tax) minus the new amount collected (net of the tax) is the share borne by the producer, or the producer tax burden.

Figure 4 illustrates the fact that the outcome is the same if the tax is imposed on the hotels rather than on the consumers.

Figure 4: A Tax on Suppliers

A $10 room tax collected from hotels shifts the supply curve facing consumers up by $10. In addition to the minimum the hotels must receive to provide a given number of rooms as indicated by S1, they now must receive an additional $10 per room to give to the city. Note that the resulting total price that consumers pay, the price that hotels receive after paying the tax, the tax revenue, the quantity, and the deadweight loss are identical to the case in which the consumers paid the tax.

Market failure occurs when resources are not allocated optimally. That is, allocative efficiency is not achieved. This can result from

imperfect information

imperfect competition

externalities

public goods

Imperfect competition and the resulting potential for unnecessarily high prices, low quantities, inferior quality, and deadweight loss is explained in detail in the previous chapter. The next sections feature more discussion on externalities and public goods. Imperfect information means that buyers and/or sellers do not have full knowledge about available markets, prices, products, customers, suppliers, and so forth. For example, imperfect information occurs when buyers pay too much for a product because they do not know about a lower-priced alternative. Another example of this occurs when producers make too much of a specific product, and not enough of another because they don’t understand the demand of their customers. Solutions to imperfect information include truth-in-advertising regulations, consumer information services, and market surveys by firms. As another example of available solutions, some countries require restaurants and hotels to post price lists so that potential customers can easily compare prices.

In contrast to the allocative, distributive, and production efficiency that are achieved when a perfectly competitive market is in long-run equilibrium, firms with market power can challenge the efficiency of the market if left unchecked. Consider a monopoly as in Figure 5.

Figure 5

The monopoly price will be Pm, and the monopoly will produce Qm. To simplify the comparison of monopoly and competitive outcomes, let’s assume constant returns to scale, meaning that many smaller firms could produce a fraction (say, one one-thousandth) of the market’s output for that same fraction of the cost. The competitive market’s supply curve would be the monopoly’s MC curve, and the competitive market’s equilibrium would be at the intersection of MC and the demand curve. Note that at this intersection, Pc = MC is the condition for allocative efficiency. The competitive price Pc is below the monopoly price Pm, and the competitive quantity Qc is more than the monopoly quantity Qm.

Along with the potential for higher prices and lower quantities in a monopoly market comes a welfare loss. In the absence of externalities (to be discussed below), the demand curve reflects the benefits to consumers of additional units of the good, and the marginal cost curve reflects the additional cost of resources needed to provide those benefits. Thus, the area abc between the demand curve and the MC curve from Qm to Qc represents the deadweight loss (DWL), sometimes called “efficiency loss” (in essence, DWL is lost consumer and producer surplus), due to a monopoly market structure. The potential for monopolies to decrease quality is an added detriment of monopoly power.

Monopolies also have some positive attributes. The potential for sustainable monopoly profits can induce individuals and firms to invent new products. Some argue that the quest for monopoly profits motivates research and development expenditures that result in important drugs and technology. In other situations, competition is not an option. Industries such as power generation and rail service have such high fixed costs that it would be impossible for a particular service area to support more than one firm. Firms in these industries are called natural monopolies.

As illustrated in Figure 6, the high fixed costs in natural monopolies cause the average total cost curve to fall throughout the relevant range of production, and the demand curve intersects average total cost while it is still falling. In this case the allocatively efficient price (PSO), at which marginal cost equals demand, would not allow profits because PSO is less than average total cost at the corresponding quantity of QSO. However, the monopoly price of PM is also undesirable because it is considerably higher than the socially optimal price and the associated quantity of QM is below the socially optimal quantity.

Figure 6: Natural Monopoly

Because competition can’t temper prices in this situation, it is common for natural monopolies to be regulated. The challenge, then, is to decide on a regulated price. If a price ceiling is set at PSO, production will satisfy the MB = MC condition for social optimality (assuming there are no externalities), but the monopoly will require financial assistance in order to survive because it will experience a loss of the difference between price and average total cost for every unit sold.

An available compromise is to set a “fair return” price ceiling at PFR. This price is equal to average total cost at the corresponding quantity of QFR. Thus, the firm will break even. The fair return price falls between the monopoly price and the socially optimal price, providing what many regulators see as a desirable middle ground between the resource misallocation caused by higher prices and the losses caused by lower prices.

The threats of excessive prices, limited quantities, and inferior quality have led the government to foster competition in industries in which it is considered beneficial. The primary tool used to restrict market power is antitrust legislation. Congress created the Interstate Commerce Commission (ICC) in 1887 to oversee and correct abuses of market power in the railroad industry; in 1914, Congress created the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) to investigate the structure and conduct of firms engaging in interstate commerce.

A summary of landmark antitrust legislation follows:

The Sherman Act (1890) declared attempts to monopolize commerce or restrain trade among the states illegal.

The Clayton Act (1914) strengthened the Sherman Act by specifying that monopolistic behavior such as price discrimination, tying contracts, and unlimited mergers is illegal.

The Robinson-Patman Act (1936) prohibits price discrimination except when it is based on differences in cost, difference in market-ability of product, or a good faith effort to meet competition.

The Celler-Kefauver Act (1950) authorized the government to ban vertical mergers (mergers of firms at various steps in the production process from raw materials to finished products) and conglomerate mergers (combinations of firms from unrelated industries) in addition to horizontal mergers (mergers of direct competitors).

There are several formal measures of market power. The Herfindahl-Hirschman Index (HHI) takes the market share of each firm in an industry as a percentage, squares each percentage, and adds them all up.  . For example, if one firm holds a 100 percent market share, the HHI = 1002 = 10,000. If two firms hold 30 percent market shares and one holds a 40 percent market share, the HHI = 302 + 302 + 402 = 3,400. The HHI increases as the number of firms in the industry decreases or as the firms become less uniform in size. The n-firm concentration ratio is the sum of the market shares of the largest n firms in an industry, where n can represent any number. For example, if the four largest firms in the cola industry hold 21, 18, 11, and 6 percent market shares, the four-firm concentration ratio is the sum of these numbers, 56.

. For example, if one firm holds a 100 percent market share, the HHI = 1002 = 10,000. If two firms hold 30 percent market shares and one holds a 40 percent market share, the HHI = 302 + 302 + 402 = 3,400. The HHI increases as the number of firms in the industry decreases or as the firms become less uniform in size. The n-firm concentration ratio is the sum of the market shares of the largest n firms in an industry, where n can represent any number. For example, if the four largest firms in the cola industry hold 21, 18, 11, and 6 percent market shares, the four-firm concentration ratio is the sum of these numbers, 56.

Externalities are costs or benefits felt beyond or “external to” those causing the effects. Some like to think of these as spillover effects. Inefficiencies arise as the result of externalities because those making decisions do not consider all of the repercussions of their behavior. When your neighbor decides how many dogs to own, she is likely to weigh the price of the dogs, their food, their health care, etc., against the joy she receives from owning them. On the other hand, she might not consider the costs imposed on you due to the dogs’ barking and biting, and the droppings left in your yard. This is an example of a negative externality because the external effects of your neighbor’s dog ownership are hurtful to you. The result of her failure to consider the costs she is imposing on you is that she will buy too many dogs. Negative externalities lead to overconsumption.

On the other hand, when your neighbor decides how many flowers to plant in her yard, she might plant fewer than the optimal amount for society if she does not consider the enjoyment you and others in the neighborhood get out of seeing and smelling them. When you decided whether or not to get a flu shot last winter, did you consider the benefits to others of not getting the flu from you if you were immunized? Flowers and flu shots are sources of positive externalities, which lead to underconsumption. It is important to note that externalities are also known as spillover effects: negative externalities are called spillover costs and positive externalities are called spillover benefits.

Figure 7 illustrates the dog ownership decision for your neighbor, whom we’ll call Mary.

Figure 7: Negative Externalities

Mary’s marginal benefit per dog decreases as she acquires more and more dogs, in accordance with the law of diminishing marginal utility. The marginal private cost (MPC) per dog (the additional cost Mary pays for each additional dog) is assumed to be constant, although the analysis is the same if it is increasing. The marginal external cost (MEC) per dog (the additional cost imposed on the neighbors) might increase because each additional dog not only barks, bites, and makes droppings but also helps provoke the existing dogs to cause even more ruckus. Looking only at her MB and MPC, Mary will own Qp dogs. To find the optimal quantity for society, add the MEC and the MPC to find the marginal social cost (MSC). The MSC intersects the MB at the socially optimal quantity of Qs dogs. This is the number of dogs Mary would own if she paid the full marginal social cost of Ps for that particular quantity. As shown with Mary’s dog, when there are negative externalities associated with a good, an over allocation of resources will occur, meaning more goods will be produced than the market demands.

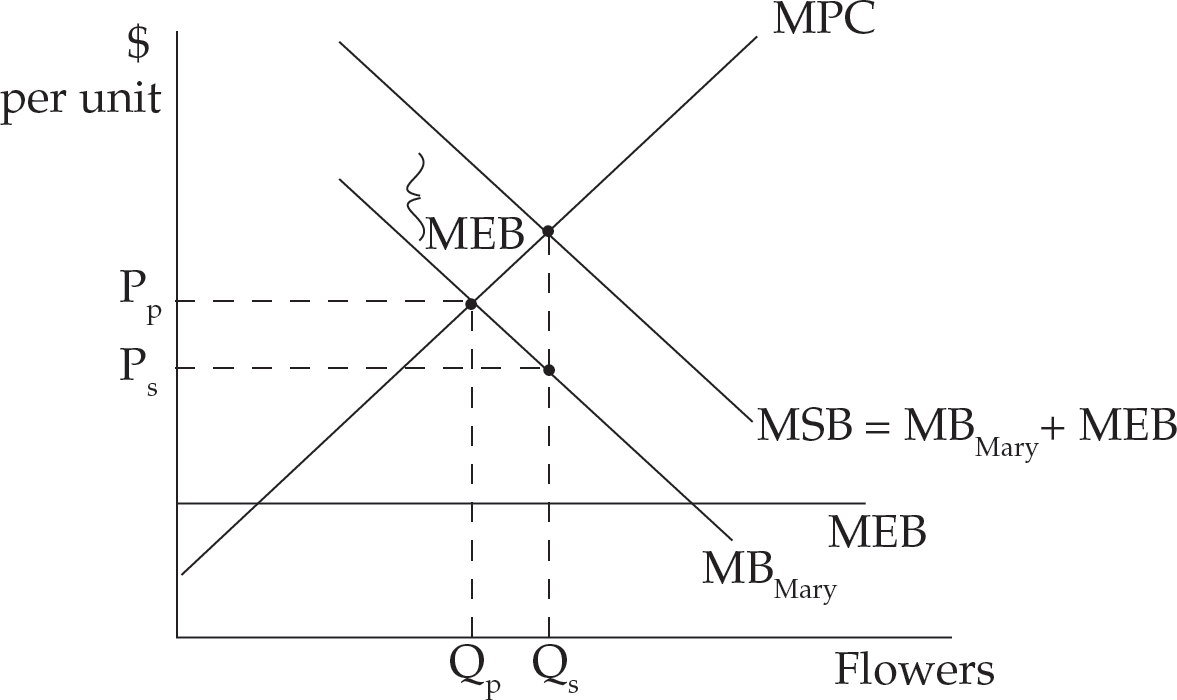

Figure 8 illustrates the flower-purchasing decision for Mary.

Figure 8: Positive Externalities

While Mary’s marginal benefit decreases, her marginal private cost increases as she purchases more flowers because she must forego increasingly valuable alternative activities to plant more and more. The marginal external benefit (MEB) is assumed to be constant for simplicity. Mary will purchase Qp flowers, short of the socially optimal Qs, which equates the marginal social benefit (MSB = MB + MEB) and the marginal cost. Mary would purchase Qs if the price were Ps rather than Pp. As shown with Mary’s flowers, when there is a positive externality associated with a good, an under allocation of resources will occur, meaning fewer flowers will be produced than the market demands.

There are several solutions to problems with externalities. Those causing negative externalities can be taxed by the amount of the MEC, causing them to feel or “internalize” the full costs of their behavior. Likewise those causing positive externalities can be subsidized by the amount of the MEB so that their private benefit equals the marginal social benefit. This is one reason why it is a good idea to subsidize immunizations and education and tax liquor and gasoline. Ronald Coase suggested that those who are helped or hurt by positive or negative externalities might be able to pay the decision makers to produce more or less of their product. The viability of such payoffs is contingent on the clarity of each side’s rights (for example, the right for a firm to pollute), and the ability of the affected parties to organize and collect the necessary funds. Alternative solutions for negative externalities include restricting the output to the socially optimal quantity (Qs) or imposing a price floor at the socially optimal price (Ps).

Note that an individual’s marginal benefit curve is synonymous with his or her demand curve, and the marginal cost curve (above average variable cost) is equivalent to the supply curve for a competitive firm. Don’t be confused if you see presentations of the externality story that replace MB and MPC with D and S. Also note that for the purpose of finding the social optimum, it makes no difference whether the MEC is added to the MPC curve or subtracted from the MB curve. Either way, the MEC creates the same sized wedge between MB and MPC, and the resulting socially optimal quantity and price are the same. Likewise, a MEB could be subtracted from the MPC rather than being added to the private MB to yield identical results.

Public goods are those that many individuals benefit from at the same time. They are characterized as being nonrival in consumption and nonexcludable. A nonrival good is one for which the consumption of that good does not affect its consumption by others. For example, Donna’s use of a radio signal does not detract in any way from Dina’s use of the same radio signal. Rival goods like food and parking spaces cannot be consumed by multiple users simultaneously.

Once available, nonexcludable goods cannot be held back from those who desire access. For example, once a country is protected by a military system, it is impossible to prevent particular individuals within the country from benefiting from that defense. Other examples of public goods include police protection, disease control, clean air, and the preservation of animal species.

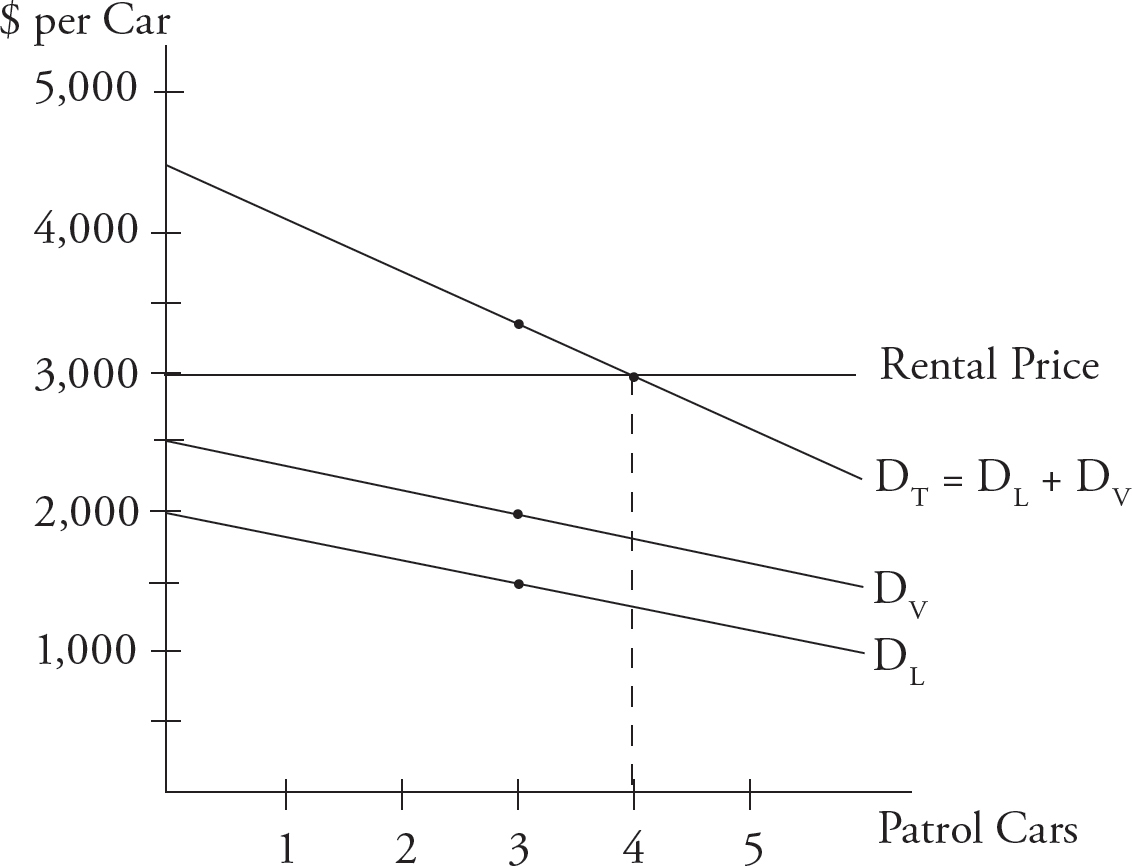

Because multiple users benefit from a public good at the same time, the demand curve for society that reflects the marginal benefit from each additional unit of the good is found by adding each individual’s demand curve vertically. Figure 9 illustrates a market for police protection that consists of only two individuals, Vernon and Linda.

Figure 9: A Public Good

Vernon’s annual benefits from the protection of various numbers of police cars are represented by his demand curve, DV, and Linda’s benefits from the same police cars are represented by DL. The total annual benefit from the third patrol car, for example, is Vernon’s $2,000 benefit plus Linda’s $1,500 benefit, or $3,500. Their town should purchase police cars until the total social demand, DT, equals the annual price of renting a police car—$3,000—which occurs with the rental of four police cars.

The problem that arises with public goods is that consumers know that they can benefit from the provision of these goods whether or not they pay for them. Even if each household gains $1,000 per year worth of benefits from military protection, a door-to-door collection to pay for the military would come up short due to the temptation for households to be free riders. A free rider is one who attempts to benefit from a public good without paying for it. Given the nonrival and nonexcludable nature of national defense, individuals have little incentive to reveal their true preferences. Instead, they might say they would rather risk invasion than pay for national defense, and then benefit from the protection paid for by others. Another classic example of the free rider problem is the difficulty of getting neighbors to pay for a streetlight in a cul-de-sac. The solution to the free rider problem in most cases is to have some form of government (federal government for national defense, a neighborhood association for streetlights) provide the public goods. Governmental units can collect money in the form of taxes, fees, or dues from everyone who benefits from the public goods and then fund their provision.

You’ve heard it before—the rich are getting richer and the poor are getting poorer. In relative terms, this is correct. The gap between rich and poor continues to widen. This is generally true on the basis of the share of income held by the richest and poorest 20 percent of the U.S. population over the past few decades. Some argue that income inequality is greater than these statistics suggest, because the rich also receive nonmonetary perks like fancy meals, housing, travel, and so on that do not show up in income reports. Others argue that the inequality trends are influenced by changing demographics such as the average age, the number of wage earners in a family, and the divorce rate. Comparisons over time of households with similar demographics yield smaller changes in income inequality.

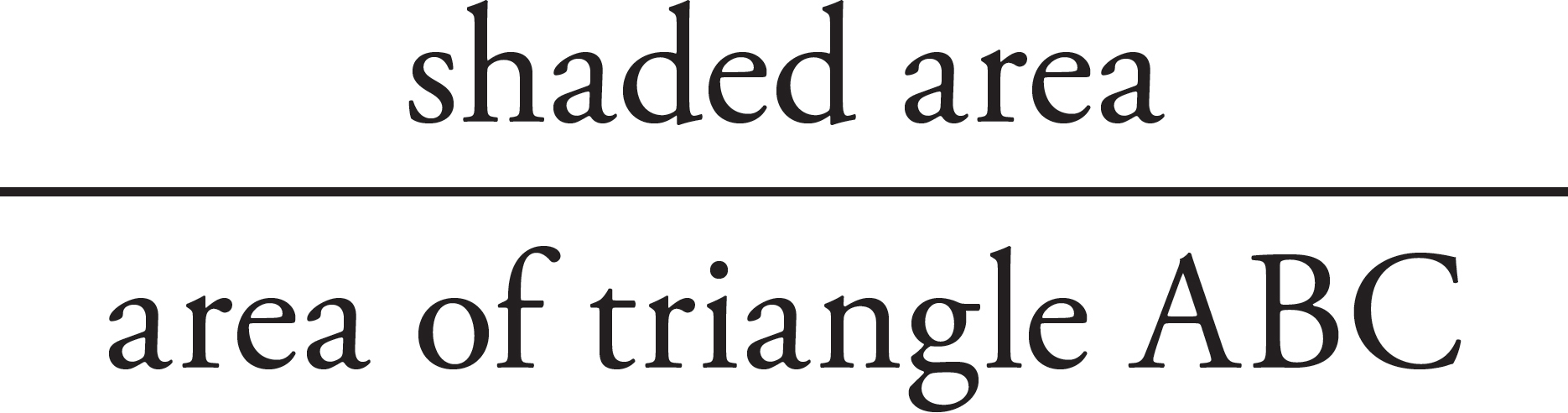

Income equality is often measured using the Lorenz curve, as illustrated in Figure 10, and the associated Gini coefficient.

Figure 10: The Lorenz Curve

The vertical axis measures the cumulative percentage of income. The horizontal axis measures the cumulative percentage of families, starting with the poorest and ending with the richest. The straight line from corner to corner represents perfect income equality because the proportion of families equals the proportion of income—the “poorest” 10 percent hold fully 10 percent of the income and so forth. The line below it is the Lorenz curve, which depicts the actual relationship between families and income in the United States. The poorest 20 percent hold only 4 percent of income, the poorest 40 percent hold 14 percent of income, and so on.

The Gini coefficient is the ratio

If income were divided equally, both the shaded area and the Gini coefficient would be 0. If the richest family made all of the income, the Gini coefficient would be 1. The Gini coefficient in the United States is about 0.48.

The poverty line is the official benchmark of poverty. It is set at three times the minimum food budget as established by the Department of Agriculture. The poverty line for a family of four is about $25,100. Nearly 12.3 percent of Americans live below the poverty line. The list below includes some of the programs that seek to redistribute income and assist the disadvantaged.

With a progressive tax, the government receives a larger percentage of revenue from families with larger incomes. In contrast to a progressive tax, which helps redistribute income to the poor, a regressive tax collects a larger percentage of revenue from families with smaller incomes. A proportional tax collects the same percentage of income from all families.

The Social Security program provides cash benefits and health insurance (Medicare) to retired and disabled workers and their families.

Public assistance or welfare typically provides temporary assistance to the very low-income families.

Supplemental Security Income (SSI) assists very poor elderly individuals who have virtually no assets and little or no Social Security entitlement.

Unemployment compensation provides temporary assistance to unemployed workers.

Medicaid provides health insurance and hospitalization benefits to the low-income families.

The Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), also known as Food Stamps, and Public Housing programs provide food and shelter for the low-income families.

communism

socialism

capitalism

price ceiling

rent controls

price floor

minimum wage

queuing cost

black/underground markets

deadweight loss

efficiency loss

excess burden

market failure

imperfect competition

natural monopoly

“fair return” price ceiling

Sherman Act

Clayton Act

Robinson-Patman Act

Celler-Kefauer Act

vertical mergers

conglomerate mergers

horizontal mergers

Herfindahl-Hirschman Index

concentration ratio

externalities

public goods

imperfect information

negative externality

positive externality

marginal private cost

marginal external cost (marginal social cost)

public goods

nonrival goods

nonexcludable goods

free rider

Lorenz curve

Gini coefficient

poverty line

progressive tax

regressive tax

proportional tax

Social Security

public assistance/welfare

Supplemental Security Income

unemployment compensation

Medicaid

Supplemental Nutrition Assistance

Program (SNAP)/ Food Stamps

Public Housing program

See Chapter 9 for answers and explanations.

1. Suppose the supply and demand for cotton in the United States are represented by curves S and D respectively in the figure above. Also assume that the world supply for cotton is so large that the United States would be a “price taker” in the world market (as represented by WS). If the United States were to open its cotton market to free trade with the world, then

(A) the domestic price of cotton would rise, and the United States would export cotton

(B) the domestic price of cotton would fall, and the United States would export cotton

(C) the domestic price of cotton would rise, and the United States would import cotton

(D) the domestic price of cotton would fall, and the United States would import cotton

(E) there would be no change in the price of cotton in the United States

2. When the labor demand curve is downward-sloping, an increase in the minimum wage is

(A) beneficial to some workers and harmful to other workers

(B) beneficial to all workers and harmful to some employers

(C) harmful to all workers and employers

(D) beneficial to all workers and employers

(E) none of the above

3. Because people with relatively low incomes spend a larger percentage of their income on food than people with relatively high incomes, a sales tax on food would fall into which category of taxes?

(A) Progressive

(B) Proportional

(C) Regressive

(D) Neutral

(E) Flat

4. If the government regulates a monopoly to produce at the allocative efficient quantity, which of the following would be true?

(A) The monopoly would break even.

(B) The monopoly would incur an economic loss.

(C) The monopoly would make an economic profit.

(D) The deadweight loss in this market would increase.

(E) The deadweight loss in this market would decrease.

5. If the government subsidizes producers in a perfectly competitive market, then

(A) the demand for the product will increase

(B) the demand for the product will decrease

(C) the consumer surplus will increase

(D) the consumer surplus will decrease

(E) the supply will decrease

6. If corn is produced in a perfectly competitive market and the government placed a price ceiling above equilibrium, which of the following would be true?

(A) There would be no change in the amount of corn demanded or supplied.

(B) There would be a shortage created of corn.

(C) There would be a surplus created of corn.

(D) The producers of corn would lose revenue due to the decreased price.

(E) Illegal markets may develop for corn.

7. Which of the following examples would result in consumers paying for the largest burden of an excise tax placed on a producer?

(A) If the demand curve is price elastic and the supply curve is price inelastic

(B) If the demand curve is price elastic and the supply curve is perfectly elastic

(C) If the demand curve is price inelastic and the supply curve is price elastic

(D) If the demand curve is price inelastic and the supply curve is price inelastic

(E) If the demand curve is perfectly inelastic and the supply curve is price elastic

Communism is a system in which the government owns all the resources in society and answers the three economic questions: what, how, and for whom are goods produced.

Socialism is a system in which the government maintains control of some resources in society, such as energy distribution, education, or health care.

Capitalism is a system in which individuals and private firms own the resources in society and answer the three economic questions: what, how, and for whom are goods produced.

A price ceiling is an artificial cap on the price of a good.

A price floor is an artificially imposed minimum price.

Deadweight loss (also known as efficiency loss or excess burden) is the loss to former consumer and producer surplus in excess of total revenue of the tax.

Calculating the effects of a new tax is tricky: the burden of the tax does not depend on who has to pay for it. Rather, the weight of the tax burden depends on the relative elasticity of the supply and demand curves for the good in question.

Natural monopolies occur when fixed costs are so high as to prohibit a second firm from entering the market.

The Sherman Act, the Clayton Act, the Robinson-Patman Act, and the Celler-Kefauer Act are important pieces of antitrust legislation.

A vertical merger is a merger of firms at various steps in the production process.

A conglomerate merger is a combination of firms from unrelated industries.

A horizontal merger is a merger of direct competitors.

A market failure occurs whenever resources aren’t allocated optimally. This can result from

imperfect competition

externalities: costs or benefits felt beyond those causing the effects

public goods: goods that many individuals benefit from at the same time

imperfect information: buyers and/or sellers do not have full knowledge about available markets, prices, products, customers, suppliers

Negative externalities lead to overconsumption; positive externalities lead to underconsumption.

The marginal private cost (MPC) of a good is the cost paid by the consumer for an additional unit of a good; the marginal external cost is the cost paid by people other than the buyer for an additional unit of a good.

A nonrival good is one for which the consumption of that good does not affect its consumption by others.

Nonexcludable goods cannot be held back from those who desire access.

A free rider is one who attempts to benefit from a public good without paying for it.

The Gini coefficient uses the Lorenz curve to calculate income inequality.

The poverty line is the official benchmark for poverty; it is set at three times the minimum food budget as established by the Department of Agriculture.