1

The Information Society Today: The Acceleration of Just About Everything

We live in a moment of history where change is so speeded up that we begin to see the present only when it is already disappearing.

R. D. Laing, The Politics of Experience

In this introductory chapter I want to sketch out the broad contours of the information society. It is a necessary step, I think, because ‘information’ in its digital form constitutes an unconscious backdrop to the lives of many, if not most, of us. It has migrated, in a very short space of time, from being novel and radical, to somewhat demotic – if not invisible. Indeed, this latter, naturalized, state is what Generations X and Y have been born into, and so it is doubly important to make these implicit relations with information technologies more explicit – the better to hold them up to understanding and analysis.

For example, the networking of society, the interconnecting of people, processes, applications, work tasks and leisure pursuits, has led to a globalized society, a ‘one-world’ context where causes and effects can reverberate throughout the entire system. This is a society where digital information is, at its root, ideological. That is to say, it was developed not as a neutral concept and neutral technology – but as ‘an ideology that is inextricably linked to the computer’ (Kumar, 1995: 7). And the computer, as we shall see in later chapters, is itself a technology that is suffused with its own political, military and industrial imperatives that evolved in the context of the Cold War era of the 1950s and 1960s. However, today, and in respect of this general introductory overview, I note here only that digital information, along with its originary logic, permeates culture and society to an unprecedented degree. It brings with it what I have termed the ‘network effect’ that is expressed as an increasingly strong compulsion to be a part of the information society; it is a compulsion linked to the needs of a neoliberal global economy that demands connectedness; requires that we synchronize to its ever-quickening tempo, a tempo that produces positive and negative effects; and insists (as part of what might be called digital information’s ‘ideological effect’) that such connectedness is also efficient and productive – and can even be fun and allow us to express our ‘individuality’. The contours of the information society, then, beyond its implicit everydayness, are revealed as contradictory. On the one hand there is a definite compulsion – a logic that is difficult to escape or avoid – that is about working ‘smarter’ and faster, and all the stresses and strains that this can bring. And on the other hand there is, undoubtedly, the ‘fun’ element: the new multifunctional mobile phone, the thrill at finding an item on eBay, or the pleasure of Skyping friends or relatives in far-off places, or expressing yourself through a personal blog. The first intellectual move to make, therefore, is to ‘denaturalize’ the information society, to define it and judge it as a humanly constructed process that is shaped by the everyday conflicts and struggles in our society that, in their turn, are reflective of larger (and more portentous) political and economic dynamics.

The network effect

To inform a young person, say, a ten-year-old (the age of my eldest), that we live in an information society would be almost meaningless. My son Theo is not stupid, but to state something like this to him would be akin to saying we live in time and space. At one level this would be a profound observation, but then again we are born into time and space and move through them with hardly a thought, so second nature have they become. ‘What’s to know?’ might be his incredulous reply. For the typical ten-year-old in a developed country (and increasingly in many developing countries too), connectivity and access to networks are simply part of what life is. We live in and live by pervasive and rapid ‘flows’ of digital information (Castells, 1996). Why did this come about? How did we individually and collectively become so au fait and casual with information technologies and the world they create? Are we really so? And anyway, do we really want to be? And do we have any real choice in the matter? We shall discuss these questions in some detail in the subsequent chapters, but a quick schematic sketch from the point of view of computer scientists – as opposed to social scientists – gives some useful background.

In their celebrated 1996 paper, ‘The Coming Age of Calm Technology’, Xerox engineers Mark Weiser and John Seely Brown forwarded the idea of ‘ubiquitous computing’. They saw this as the third stage of computer evolution. The first stage was the ‘mainframe era’, which saw the arrival of bulky, hot and slow ‘data processing’ or ‘defence calculator’ computers that in the 1950s and 1960s took up the space of a couple of large rooms. They were devised and built by corporations such as IBM and were used mainly for military research into thermonuclear weapons. Second was the ‘personal computer (PC) era’, beginning in the early 1980s, that was the result of innovation in micro-processing technology that was able to put a standalone (non-networked) computer on an office or home desktop. After that came what the authors called the ‘transition phase’ that began in the 1990s with the growth and increasing sophistication of the Internet and computer networks in businesses, in the universities, and in what Howard Rheingold (1993) called ‘virtual communities’. Weiser and Seely Brown distinguish this transition as one of ‘distributed computing’. This third phase they calculated to occur over the years 2005–20 and it would be distinguished by what they term ‘ubiquitous computing’. Here the Internet and embedded microprocessors in everything from garments and mobile phones, and from bus tickets to refrigerators, will push an awesome and invasive computing power into the background, just below the horizon of our consciousness, to emit its ‘calming’ effect. Through attention to the design of ‘calm technologies’, the authors argue, the era of ubiquitous computing – which we have already entered – will herald a radically new age. It is to be an era of perfect ‘man–computer symbiosis’ that Internet pioneer J. C. R. Licklider had already dreamed of in the early 1960s, where ‘men will set the goals, formulate the hypotheses, determine the criteria and perform the evaluations [and] computing machines will do the routinizable work’ (1960). Clearly taking their cue from Licklider, Weiser and Seely Brown predict that ubiquitous computing and ‘calm technologies’ will create an information society where people ‘remain serene and in control’ (Weiser and Seely Brown, 1996).

We need only look around to know that computing is certainly ubiquitous, but whether or not it is ‘calm’, unobtrusive and enables us to free up our lives for higher things, as these technological utopians predict, will be a major focus of this work.

For good or ill, computers are all around us, enveloping us in an information ecology that is comprised of networks, systems, processes, technologies and people – and they are not about to go away or become any less prevalent. Ten-year-olds, teenagers and adults inhabit this information society, and it pervades almost everything that we do. Our everyday working lives that take place in jobs in manufacturing industries or in the provision of services have either been radically transformed through computerization or have evaporated into obsolescence. Millions of us do new jobs in new industries that did not exist in our fairly recent past. The nature of business itself has changed due to the transformative effects of computerization. For example, the primary goal for large corporations, and for many smaller businesses too, is – as Jeremy Rifkin puts it – to become ‘weightless’ (2000: 30–55). That is to say, to get away from the ownership of fixed assets such as factories, machines, fleets of trucks and so forth that dominated the productive forces of an earlier age. In this so-called ‘new economy’, intangible assets, above all ideas, are ‘more powerful than controlling space and physical capital’ (Rifkin: 55). Ideas, moreover, are eminently suited to computerization, to be transformed into processable information through binary logic. Indeed it is ideas that make Microsoft, or Apple, or Google what they are – huge informational entities that are comprised of few or relatively few fixed assets. The comprehensiveness of this process means that the need for weightlessness is not confined to high-tech companies either. More traditional industries, those that still have comparatively high percentages of fixed assets such as plant and machinery, also use information technologies to their utmost capacity to speed up production, make production and distribution more flexible, and be more able to respond to changing customer demand. Automobile manufacturers, for example, the quintessence of the ‘old economy’ mode, are now awash with flexible computerized systems that make the car factory an utterly different business to what it was only twenty-five years ago.

In the information society, the age-old and modernist conception of there being some kind of bifurcation between private life and work life has been made as redundant as the 3.5-inch floppy disc. Flexible working systems, the proliferation of part-time and casual working, and the increased working load that many now have to bear, mean that the once-distinct and regularized times for work and rest have become blurred – if not eliminated altogether (Schor, 1993). Networked computers, mobile phones, PDAs, wireless laptops and so on mean that we are far more mobile and no longer so tied to the office desk or designated workplace. But they also mean that our work is able to follow us wherever we go. Being ‘always on’, as the network advertisers like to remind us, is an allegedly wonderful thing that allows us to ride the cusp of the high-tech wave. But it also means that the student who works part-time is made available at short notice to a boss who suddenly needs more staff for a couple of hours; and means that the office worker is made available to read and act upon a report that will be emailed to her at home at 10 o’clock on a Friday evening, with a response due by 9 o’clock Monday morning. There is today a distinct pressure that compels the individual within the network society to be connected and ‘always on’. And so if you want a decent job and a career, or to start up a business of almost any sort, you will need to be a willing and connected ‘node’ in the networked economy. The result has been that there are fewer and fewer refuges in time and space where you can be outside the pull of the network effect, to resist the virtual life and to experience another reality.

The pressure to be connected exists at almost every level. In the developed economies it is now almost impossible to go through high school and university, for example, without what would not so long ago have been considered advanced computer user skills. Not only that, but students must also be able to access networks and be online for considerable amounts of time if they want to progress through the curriculum. Universities have taken up the challenges of the information society with alacrity and are amongst the most computer-filled places in the world. Indeed these institutions, especially in the Anglo-American economies, see themselves as progressively more ‘weightless’ businesses that exist largely to deliver pedagogy to its ‘customers’ or ‘clients’ through flexible computerized systems (Currie, 1998; Hassan, 2003; Bates, 2004). The Internet has even become a way for the elite universities such as Yale and MIT – who set such reputational store by their ‘traditions’ – to go global and decidedly non-traditional. Both these universities have put course materials online for free, with Yale going one better by uploading video lectures in 2006. This acts as a global branding and marketing exercise for these and the other universities who will doubtless emulate them. By offering access to free material, the hope is that users will then want to get the Yale or MIT degree by becoming actual online students and paying for the privilege. In the information society where the ‘user pays’ principle dominates, the keenly contested ‘student market’ thus truly becomes universal through such hi-tech practices. No longer do you need to go to the physical university to get a degree – the university, even the biggest, most prestigious and traditional of them, will come to you (at a price). We see that the logic of acceleration imposes itself here, too, with degrees becoming ‘virtual’ and ‘flexible’ and ‘fast-tracked’. A typical example of the marketing of the alleged attractions of gaining a three-year degree in two years comes from the website of a UK university that claims this compressed degree will ‘accelerate your career: [allowing you to] gain a real advantage by entering the job market a year earlier. You’ll save money and get on the career ladder sooner’ (University of Northampton, 2007). Note that the emphasis is not on learning, or the acquisition of knowledge, but on efficiency, and getting into the workforce sooner so as to save time and money.

Possibly it is in the realm of entertainment that the orbital pull of information technologies has been most apparent and habit-changing. For example, television executives have been increasingly vexed by the fact that viewers are switching off and logging on instead. Time spent online has what is termed a ‘hydraulic’ effect in that it diverts from time spent on other pursuits (Markoff, 2004). And while online increasing millions consume and contribute to the growing ‘flows’ of information that make up the information ecology. We do this, for example, by generating billions of emails every day. Add to this the uncountable text messages, voice calls, video conversations, picture sending and so on, and you get some idea of the ‘hydraulic’ gravitation towards online activity. For those who spend extended periods online, outside of the formal work situation, we need to look to the video gamers, the growing millions of users who are the simultaneous consumers and creators of an entertainment industry said by Bill Gates in 2003 to be bigger than the movie industry. Indeed, accountancy firm PricewaterhouseCoopers predicted that the industry (game consoles and software sales) would expand from $21.2 to $35.8 billion from 2003–7 (PWC, 2005). The market, moreover, has enormous room for further expansion as the network society spreads and deepens. For example, the number of users in China went from around zero in 2000 to 14 million by 2005; and industry leaders Microsoft, Nintendo and Sony are deliberately seeking to expand the global market out from its young male demographic (Joseph, 2005). It is a strategy that seems to be working, probably to the further consternation of TV industry executives. For example, journalist and media theorist Aleks Krotosi observes that in South Korea, for example, ‘practically every street in Seoul has an Internet café – a “PC Bang” – where kids and OAPs game side by side’ (2006). Moreover, online games, or what are called ‘massively multiplayer online role-playing games’ (MMORPG), are exploding in popularity. One game, Lineage, held the record for the largest number of players for a few years until the current mother of all MMORPGs, World of Warcraft, was released in 2004 and attracted up to 7 million users worldwide. As Krotosi notes, however, Lineage is still hugely popular in South Korea, with 4 million users, which is reportedly more than the total number of TV viewers (Krotosi, 2006).

Add to this the immense popularity of video-enabled mobile phones, DVDs, iPods, PlayStations, Xboxes, GameCubes, Wiis and the rest, and it becomes clear that in the information society entertainment is a dominant ‘hydraulic’ force on the time people spend online; time that is progressively more screen-based, digitally transmitted, and comes through networkable devices.

This mass migration to digital forms at work and in leisure brings us to the nub of the ‘network effect’. We see an example of this when, say, your best friend buys a mobile phone. The action exerts a certain social pressure, a pressure which, depending on the circumstances, either gently cajoles you into buying one yourself at some stage, or compels you into getting one the very next day. Those who have a mobile and reflect upon their reasons for purchasing it can easily understand this phenomenon; and marketers have understood this dynamic for a long time. In the information society taken as a cultural and economic totality, however, there is another kind of network effect at play. That is to say, to be part of the information society and to be affected by its pressure and its imperatives, you don’t even need to be connected – you only have to live and work in a modern or modernizing economy. It is important to recognize that so deeply and powerfully has the information society transformed our world that it moves us as workers and as consumers in ways we hardly register, except often as a form of stress. Even if we don’t sit at a networked computer screen, or walk around with a mobile phone clamped to one ear, as millions of people do, these others who are ostensibly ‘unconnected’ are nonetheless linked to vast networked flows of information that create momentum and speed, to produce what Hartmut Rosa has termed a generalized ‘social acceleration’ (2003). In other words, as the social world gets faster, its centripetal force (the network effect) draws us all in whether we are connected or not.

Let me explain this idea a bit more through an example. It is still common for mail sent through traditional means to take days or weeks, but now such time lags for communication seem anachronistic, from a very different world indeed. Letter writing is in decline mostly because ‘society’ now deems it too slow, and this will affect the unconnected through the closure of many post offices, the disappearance of uneconomic postboxes, the increasing cost of postage and so on. The network effect thus presents us with a choice: which is either to get connected and speed up your mode of communication – or be left behind. To ignore the network effect is to miss out on what might be important information, to lose out on opportunities or to be ignorant of changes that can affect us in our everyday lives. In the information society, to be in a position of unconnectedness is to run the risk of sinking rapidly from the social, economic and cultural radar.

We experience the network effect at the level of the individual, but it is felt too in institutions and industries that must also constantly adapt and synchronize – or die. This is clearly evident in ‘old’ media such as television, newspapers and radio. These media have had to speed up in the frantic quest for relevancy in the information age. Any TV show worth screening (and many that are not) will now have its own website where viewers can email each other about it, give feedback on what they like or dislike, and so on. Indeed, through podcasting and digital streaming, television content is migrating online in a big way. The BBC, for example, podcasts much of its audio content from its radio stations, thereby keeping listeners connected as if they were still listening to ‘old media’ radio. In late 2007 the BBC also launched its iPlayer which allows internet users to view BBC video content for up to seven days after it went to air – again allowing ‘old media’ players to not only keep people watching their content, but also take a lead in some ways, in respect of the shaping of how people use the Internet.

Newspapers saw the writing on the wall at least a decade ago and went online in a big way. Good examples are the British-based Guardian and the New York Times. Both are profit able enterprises, offering a combination of free and paid-for articles. For instance the Guardian through its Guardian Unlimited site gives much of its content away for free. And for a fee it gives the functionality to print the paper as it appears on the newsstands, enabling the reader to get the ‘morning’ paper in any part of the world at any time. The squeezing of time and space through information networks means that, for example, someone in Australia is able to read the London morning edition of the Guardian before most Londoners are out of bed. Through its blogs, the Guardian allows a globalized readership to immediately comment on op-ed pieces by being able to directly email the author and/or enter into a debate with other respondents. Radio too has gone online with most large commercial stations, and even small subscription-supported stations, offering streaming audio of their content, having separate web pages of their programmes which feature their popular hosts, and so on. In media and in business more generally, and at the level of both the individual and society, the pressure of the network effect to become part of the network logic is ever more compelling, bringing with it an acceleration of economy, culture and society.

The speed effect of the network effect

The network effect means that old media speeds up, communication speeds up, economies speed up and life speeds up. And this fast pace of life, as we shall see in chapter 6, has its benefits and its costs. But before we get to that discussion, I want to preface it – indeed preface the whole book – with a sharper idea of speed and what it means in the context of the information society, and how it is able to produce both dreams and nightmares for those who are part of it. Speed is built into the logic of computers. The perceived need to process information faster, it could be said, is their raison d’être. And speed can be good or bad, depending on the circumstances. We can enjoy instant communication with friends or loved ones over great distances and this is unambiguously good; but, as any stage magician knows, speed also blurs perception and dulls acuity. It can confuse and muddle our thinking, and the pressure of speed can cause us to act too quickly (or not quickly enough) – with results that may be decidedly bad. Think of reading that op-ed just mentioned from the Guardian, hot off the press so to speak on your computer. Reading on, fifteen hundred or so words later, you come across the author’s email address, and are invited to submit comments to the blog that will go online almost immediately. You are enraged by the piece and fire off a response quickly (because you can, and because the network effect prods you on), and suddenly it is finished. You press the ‘send’ button. Seconds later, your email has flashed through and your comments are uploaded for all

the world to see. And then you read it and think: I spoke too soon. I should have said this; did not really mean that; or could have expressed this point more clearly; that sentence makes me sound like a bigot. Too late. The dream of instant communication and information sharing has become the nightmare of personal embarrassment and public (global public!) ignominy. The best you can hope for is that no one will recognize your username, or that you will be ignored completely. A moment of red-faced embarrassment may be all that will transpire, but as we will see below, the pressure of speed may have a much more disastrous effect.

Speed and illusion

The speed effect of the network effect can also create an illusion. The illusion in the above example may be that, notwithstanding the potential global audience your words have, no one will ever give your reply a second thought. It could be that for all the alleged potential of computerized communication, you might as well have not bothered. But let us look at the issue of speed and illusion a bit more closely. A lot of books begin their chapters with quotations. This one, as you will have noted, is no different in this regard. It’s a serviceable way to get the reader’s head into a certain space, to think down this or that line of reasoning, and to act as a kind of mise en scène for the narrative that is about to unfold. Inserting a quotation has also, by the way, been an appropriately self-effacing way of conveying to the reader your extensive range of learning. Therefore, something judiciously chosen from Plato’s Republic would imply that I had read it, and that my thesis or argument is suitably profound and is supported by the immense intellectual tradition of 2,000 years of Platonic learning in Western civilization.

In truth the above quote was picked, more or less at random, from a Google search function that trawls its directories for quotations downloaded from the Internet. It took not the two or three days it might take to read a book – but less than two minutes. Nonetheless, the quote is a fairly good one; it’s apt and it fits with what I want to say in this opening chapter. Incidentally, Laing’s book The Politics of Experience has in fact taken up a bit of space on my bookshelf for a long time, but has been completely unexplored since the day I brought it home from a second-hand bookseller. I have it before me now and discover inside its pages a tram ticket dated 13.11.89. I have no idea if I purchased the ticket or some previous owner did. However, precisely how I came by these particular words, floating in cyberspace, disconnected from the rest of Laing’s writing, is illustrative of what I want to write about in this book. The very ease with which I could pluck it from the digital ether is in itself nothing short of astonishing if we pause for a while and reflect upon this fact, a fact we now routinely take for granted. And so a major aim of this book, thinking about you the reader, is that it is intended, in a very modest way, to be a ‘pause’ for reflection within the maelstrom of technological transformation.

This short digression is also intended to highlight the fact that the information society is a society in constant flux and change. It moves at an ever-quickening pace and causes the ties that bind us to the old, to the traditional and to the known, to easily slip their moorings. In such instability, illusions are easy to create, as I showed with the example of the quotation. I didn’t need to read the book, or even reach to my bookshelf to flip through its index. It was readily to hand in cyberspace and accessible through a few keystrokes on my computer. Moreover, what is available to me in the ‘network of networks’ is being added to, massively, every hour and every day of the year. Hundreds of billions of web pages containing almost every conceivable idea and utterance and image are now within my reach. Similarly, the information creating and gathering technologies that sustain these networks and flows of information are being improved and made more efficient and powerful every hour and every day of the year.

In the midst of ongoing change, everything is constantly new. But what is disturbing about this is that we have quickly become used to novelty; we are soon jaded by the next generation of this or that phone or computer, or digital gadget. We become jaded because the fruits of the information society are ultimately unfulfilling. The illusion is laid bare for only a short time, however, until the next new thing briefly distracts us and beguiles us. The speed of the action, in the construction of the seemingly ‘new’, disguises what is essentially an empty gesture. It is the illusion, in other words, that constitutes the reality of the information society.

A caveat needs to be inserted at this point. To say that the information society constructs illusions – and it could be argued that many of us know this at some level of intuition, such as when the computer is found to be too slow, or the iPod malfunctions too easily, or when the new software just complicates things even more – is not the same as saying that what is being projected in the rapid flickering of the screen and in the flows of digital networks is necessarily and always false. Illusion and reality exist side by side; they intermingle and interchange. Your illusion may be my reality and vice versa. It would follow that if truth constructs reality, then especially in our postmodern world, we need to always keep in mind that truth is provisional (Lyotard, 1979). As a community and society we need implicitly or explicitly to agree that something is true – such as the once widely held belief that plastic was a cheap, flexible and durable substance that would transform the way we live. It did. But new knowledge (new context, new understanding) showed that it is made from a finite and constantly more problematic source (oil) and it does not easily degrade, and is destined to stay inert in landfill as waste for hundreds of years. Truth then can become a chimera when the context that sustains that truth changes. As Helga Nowotny noted in the context of knowledge production: ‘new knowledge arises under changed conditions of creation and in changed structures of organization’ (1994: 87).

To try to make some sense of this rather tricky conundrum in the context of the information society we need first to ask: what is the illusion of cyberspace meant to portray and, second, when (and for whom) does the illusion (the dream) attain reality?

A digital dream

Not long ago I was at an academic conference in the UK where a range of speakers, from universities, from governments and from businesses, gave their views on how to engage with the future. Ways to think about time obviously formed a core theme of the conference. I gave a paper which argued, in short, that liberal democracy as a political practice functioned at a particular pace and cannot be overly rushed, and so therefore is unable in many ways to function properly (democratically) in our high-speed information society. At the parallel sessions, where I attended to hear papers, there was always the same person who seemed to be attracted to the same ones as me. I could see from the obligatory name badge that he was not an academic from a university, but a corporate employee, an American living in Paris and working as a consultant on future strategies for a high-tech multinational. He dressed immaculately, in contrast to most of those present. An expensive watch complemented his crisp shirt, silk tie and dark business suit. He looked poised, confident and relaxed. He sat at the front row of each session with a tiny Sony laptop on his knees and typed on it at high speed, using all his fingers in the manner of a super-efficient typist. He never looked up while the speaker gave his or her paper, just typed. After each presentation, he would close his laptop and quickly raise his hand as he lifted his head from his computer, all in one seamless motion. He was always first in with the questions and they were always calmly put, incisive and to the point, ensuring that he finished with his own counter-point as well (he never seemed to agree with the academics). He came to hear my paper and I could see him as I spoke – head down as usual, clicking away thoughts that were immediately fixed on to his computer’s hard drive. When I finished speaking his hand shot up even while the mandatory ripple of applause was going round the room. He asked, as I anticipated, about my argument regarding ‘social acceleration’, about how and why information technologies have speeded up society to an unprecedented degree.

I must have given him an unsatisfactory answer because afterwards, at a tea break, I noticed him softly clicking his mobile phone shut and making a straight line towards me with a broad smile on his face. He was an affable and supremely smart fellow, and I could see as he made his way towards me that I needed to come up with better answers this time. Over the following twenty-five minutes he didn’t actually ask any questions at all. He simply argued his case that ‘social acceleration’ was a myth. Time today in our postmodern, information society was actually going slower and it was information technologies that were causing this to happen – the polar opposite of my proposition. His position was actually one I’d heard before, and a version of it is well put by Jeremy Stein in a collection, Timespace (2001: 106–19). For my American interlocutor, however, the really radical speed-up in time and space occurred not for him and his generation, but for his great-grandparents who had moved from Russia during the early part of the twentieth century. For his forebears and for everyone else in the USA at that time, the introduction of the telegraph, the motor car and the railroad were the epitome of what Marx (and he knew his Marx) called ‘all that is solid melts into air’ – meaning that it was their world that had been completely transformed. It was they who truly experienced the temporal rupture from the pace of the countryside, to the drive of the mechanized city; theirs was a world out of their control with larger forces than they could comprehend, overwhelming them until they gradually learned to adapt and synchronize to the new pace of life, to twentieth-century modernity. This was what ‘speeding-up’ was all about, he maintained.

He, on the other hand, was in the process of constantly evolving with the information society. For example, the call he had been making previously was to his five-year-old daughter who was sitting on a swing in a Paris playground. What could be more life-affirming, positive and convenient? Where was the so-called ‘disorientation’ that the network society was supposed to induce? Information technologies conferred control and autonomy upon him, he insisted. As far as he was concerned, life would be impossible without ICTs, as would the company that employed him. But this did not mean he was a slave to them. He told me he could switch them all off and go hiking, which he regularly did; he loved his job as he dealt with ideas and communication, and real people, and he made a lot of money and he had a wonderful family who were all bilingual. Life was good. The pressure of work he could deal with because he was in control; he controlled its pace and never felt harried or rushed. What was all the fuss about?

A digital nightmare

There is an immensely popular computer game called The Legend of Mir 3 that online players from around the world can get involved in. Like many in the gaming world it is of the fantasy genre, full of heroes, mysteries, castles, monsters and gods. Its website defines it as:

a massive online multiplayer role-playing game based in a mysterious Oriental-style world. In The Legend of Mir you can be a powerful warrior and develope (sic) your ability in close combat, a skilled wizard with a whole set of spells or a mystic Taoist provided with inner spiritual powers. (Legend of Mir, 2007)

Again, as with many of these games, combat is the thing. In the different ‘quests’, you fight enemies and in defeating them become stronger and gain trophies and weapons, and graduate up the levels of expertise. Characters are represented by ‘avatars’, which in virtual-reality games are icons (symbols or pictorial images) that represent the user. Avatars are important. For serious gamers, they represent ‘real’ things that vitally affect their online status and their online persona, such as whether they are heroic, or wise, or have attained a high level of combat proficiency. Swords are of course important avatars in such virtual-reality games, as would be, say, a laser-power gun in a more futuristic game. Some swords in Legend of Mir are ‘wooden’ and others ‘metal’, and their skilful and ‘honourable’ use can propel the user up the various levels. Indeed, just as with a commodity or thing in real life, these avatars can be bought and sold, so a novice with a lot of real money can purchase a prized sword to help her progress – or at least gain some online status. Avatars can be bought and sold online between users at an agreed market price on websites such as eBay. As one seller noted in his/her eBay auction for a female warrior avatar for the Legend of Mir, the buyers ‘are paying for the time it takes me to earn this char[acter] and items involved’.

The weaving of the evanescence of virtual reality into the concreteness of real life – the spending of real money to buy virtual things – is testimony to the power of the dream in online gaming. However, virtual dreams can and do have nightmarish real-life consequences. In mid-2005 the gaming blogosphere buzzed with the news that a gamer in China, a Mr Qiu Chengwei, killed another gamer, Mr Zhu Caoyuan, in a dispute over a ‘dragon sabre’ that is a virtual sword for use in the Legend of Mir. Mr Qiu loaned his sword to Mr Zhu, who allegedly sold it to a third party. BBC News Online reported, curiously in its ‘technology’ section, that: ‘Qiu Chengwei stabbed Zhu Caoyuan in the chest when he found out he had sold his virtual sword for 7,200 Yuan (£473)’ (BBC, 2005). The China Daily Online reported on the same day that Mr Qiu had been sentenced to death, a penalty that could be ‘commuted to life in prison if he behaves well in jail, and no other crimes relating to him are uncovered’ (China Daily, 2005).

The virtual dream of heroism, of warrior status and online respect shattered into a real-life nightmare for Mr Qiu and for the family of the victim of his stabbing. The power of the information society to colonize the lives of individuals and so to shape and help determine their thoughts and actions could not be clearer than in the case of Mr Qiu. The contrast between cyber dream and digital nightmare, indeed, could not be more marked than that between Mr Qiu and my conference colleague. For one, the information society is replete with powerful resources that enhance one’s control over online and offline life. Personal self-confidence and success in career and family life are the result of a low-key and positive relationship with information technologies. For the other, the network effect has had much more drastic consequences. An essentially solitary pursuit builds up a virtual world of importance where it is no longer clear where reality begins and ends. Where morality begins and ends becomes fatally blurred too. The commonplace of virtual death crosses over for a single instant into the death of a real individual, to change forever the lives of all those involved. The reality of the nightmare begins to assert itself for Mr Qiu when his digital dreaming is no longer possible in a Chinese jail cell that is presumably not modem or wi-fi connected.

Digital dream and cyber nightmare have been contrasted here in two real-life, but nonetheless singular, instances. What could they represent in our pursuit of a coherent understanding of the information society? In his book Mediated: How the Media Shape Your World (2005), Thomas de Zengotita argues that to live in the information society is to dwell in a world of purported choice, a veritable ‘field of options’ made plentiful by capitalism where being connected means that almost anything is possible. Crucial in this respect is our attitude to the choices offered. Optimally, this ‘stance’ is a reflective position that gives context to what is represented to us as consumers in the digital age. On this question of choice, de Zengotita writes that:

On one hand it’s a party, a feast, an array of possible experiences more fabulous than monarchs of the past could even dream of . . . On the other hand, an environment of representations yields an aura of surface – as in ‘surf’. It is a world of effects . . . We are at the center of all the attention, but there is thinness to things, a smoothness, a muffled quality. (2005: 15)

A few things to ask to begin with are: how do we know what we want? And when we choose, what is the consistency of the ‘realness’ constructed within the information society? And, in the process of choosing, do we really choose or are we confronted by a fait accompli, by the illusion of choice? I am not in a position to judge the ‘realness’ of my conference colleague’s life within the information society – only he can really do that. Similarly, Mr Qiu’s prison cell is real, but I am in no position to pronounce upon the texture of his previous online life, an undoubtedly complex and ultimately fraught relationship between reality and virtuality.

What my examples did illustrate, however, were the opposite ends of a continuum that we must now try to place in some kind of contextual and analytical framework. To construct an analytical framework is by necessity to take an intellectual stance. This comprises a series of biases and intellectual proclivities that arrange the materials I use and shape the way I make sense of the world. It would be disingenuous for me to admit otherwise in a book that draws together some fairly commonly agreed salient perspectives on the information society and organizes them into some kind of narratable whole. The only alternative in a strictly ‘neutral’ rendering of these perspectives would be to simply describe them in isolation with no analytical commentary based upon a worked-out position. This would be an exercise in futility and make the process of understanding the information society an impossibility. What I present over the following chapters then is an unavoidably biased perspective. If nothing else, this gives you the reader a foothold in the process of comprehension, a story to take or leave, or to take bits and leave bits. This in itself would have been a success, because even to reject the book’s argument is to place yourself in opposition through worked-out biases of your own. What I hope the book will achieve most of all is the urge to find out more, to support or critique, preferably to do both at the same time, thereby adding to our general social understanding of the information society and what it means.

Speed, time and social life

Close readers will have spotted some proclivities already. Principal amongst these would be my conviction that if we understand what the speed of information technologies means in our society, then we have an insight into the nature of the information systems that surround us. Speed and time, as we shall see, makes an understanding of the information society both more difficult and easier. More difficult, because in simple terms if society moves more quickly, if we as individuals literally have less and less time to spare, then we are less able to reflect adequately upon our position; on why we do the things we do and why our society seems to be the way that it is. On the other hand, if we have a conceptual key to use, and if we take the time to consider and reflect – to work against the prevailing logic of speed in business, in academia and life more generally – then certain things may become more apparent.

I wrote that the quotation by R. D. Laing at the beginning of this chapter took me a couple of minutes to locate and choose. And so it did. However, what my eye sought out in a semi-unconscious act of elimination in the selection of this particular quotation was the term ‘speeded-up’. And when I reread it and thought about it more, the sense of it seemed to be an idea worth discussing further. Let us return for a moment, though, to de Zengotita’s Mediated. Consider, in the context of speed, what he terms an ‘enviroment of representations’ in the words cited above. Information technologies mediate the world – bringing (re-presenting) the world to us – in a maelstrom of fast-moving images, signs and symbols, creating what I earlier termed an information ecology. The ever-increasing speed of information technologies creates a blurring effect where concrete reality and virtual reality become difficult to distinguish. The speed of daily life creates what de Zengotita describes as a ‘numbness’ that begins to invade our sense-making capacities and our perception of coherence about the reality of the world. He goes on to observe that ‘our state of numbness’ is constituted by being:

swamped by routine activities. The old-fashioned superficiality of routine blends seamlessly with the new superficiality, the surface quality of ubiquitous representation – and this hybrid accelerates constantly, as you take on more and more. (. . .) The result is a simulation of reality convincing enough to pass for the original, for most of us, most of the time. It is only when the ultimate reality descends on us in the form of a tragic accident, illness, death or a miraculous recovery, the birth of a child – only then does that simulation stand revealed for what it is. (2005: 186)

Laing’s quote suggests that as time unfolds, and as the present recedes into the past, only then do we have the proper perspective on what happens in the ‘now’. The present is too full of life’s complex ‘reality’ demanding our immediate attention, that only when the present becomes the past do we have time to consider what the present means (or meant). Laing’s words were written in 1967 and so I cannot impute to his words the consequences of the information technology revolution, nor can I suggest that this is what he meant by ‘speeded-up’. What I can argue – and this will be conducted in more detail in chapter 6 – is that life today, due first and foremost to the effects of ICTs, has indeed ‘speeded up’, and has accelerated to a degree much greater than Laing could ever have imagined at that time. Moreover, it is important to note that as a psychoanalyst he did not argue a social theory of speed per se – but a psychiatric theory of perception. However, if we think about social acceleration as emanating from a technological basis, then speed and perception become part of the same process. We can see this as a blurring of perception or ‘numbness’ where the ‘now’ does not inexorably recede into the past to supply a perceptual vantage-point from which you can then make sense of the world, as Laing would have it. It stays with you.

A broad definition of the information society

To end this introductory chapter, I want to define the information society so as to present it more clearly as an object of analysis. Too often and for too long, politicians, info pundits and the media more generally have referred to the ‘information society’ in the implied or explicit context of ‘we are all on the Internet now’ or ‘almost everyone has a mobile phone’. As will be apparent by now, I take it to be infinitely more than these trite and narrowly focused statements suggest.

At its broadest level of conceptualization we can begin by saying that the information society is the successor to the industrial society. Information, in the form of ideas, concepts, innovation and run-of-the-mill data on every imaginable subject – and replicated as digital bits and bytes through computerization – has replaced labour and the relatively static logic of fixed plant and machinery as the central organizing force of society. The modern industrial society of relatively ordered and organized dynamics has been transformed, essentially since the 1970s, into a postmodern information society where disorganization and fragmentation are its salient characteristics (Lash and Urry, 1987; Jameson, 1991; Kumar, 1995). Not so long ago, in sociology, in political theory and so on, the term ‘industrial society’ related mainly to the world of work, and to the ‘modes of production’ such as Fordism that gave this society its particular shape and form. By contrast, the information society (or as Manuel Castells (1996) has termed it, the informational society) has been powerfully connected to the idea of a paradigm shift, that is to say, to the insertion of fundamental change across every sphere of life. Daniel Bell, as we shall see in the next chapter, saw the function of information and the role of ‘information workers’ as being the core elements of what he termed the ‘post-industrial society’ (1973).

Bell’s thinking on the centrality of information has been borne out in many ways, but he did not envisage the all-transforming power of computerization. The transformative nature of computers was recognized in the work of the late Rob Kling, for example, Director of the Center for Social Informatics at Indiana University in the USA. Kling viewed computers as ‘enabling’ technologies that not only created new, information-based industries such as the Microsofts and Intels of this world, but they have also completely transformed old industries and institutions (Kling, 1998). ‘Old’ industries such as steel production and automobile manufacture (those that did not succumb to the shock of 1970s–80s economic restructuring, that is) became essentially ‘renewed’ through computerization, automation and the use of flexible processes and flexible employees. These and other dominant industries such as manufacturing and construction now show only the barest resemblance to their recent ancestors of the post-Second World War era.

The logical evolution of this process was the networking of industries across sectors and across space. Manuel Castells’s analysis of this emerging information order has not yet been surpassed for both his clarity and in his establishing the central ideas through which we make sense of it. On the networking process, for example, he writes that:

Networks constitute the new social morphology of our societies, and the diffusion of networking logic substantially modifies the operation and outcomes in processes of production, experience, power, and culture. While the networking form of social organization has existed in other times and spaces, the new information technology paradigm provides the material basis for its pervasive expansion throughout the entire social structure. (1996: 469)

Castells here uses what may appear to some as fairly high-flown language. The phrase ‘entire social structure’, for example, may seem something of an exaggeration, and indeed it is always prudent to recognize that there will always be forms of social, cultural and economic life where the power of information and the sprawling reach of networks have been relatively slight. However, these realms are diminishing as the information society spreads and deepens. The concept of the network effect that we have just discussed, for instance, gives some indication of how, without exaggeration, the ‘entire social structure’ may be affected. But let me give a more specific example. As Terry Flew (2003: 24–5) reminds us, the al-Qaeda attacks on the USA on September 11, 2001, could not have been conceived, organized and carried out without the use of sophisticated communication technologies. Mobile phones, email, satellite phones, Internet websites and media such as the al-Jazeera television station allowed for the networked ‘flow’ of ideas of perceived injustices towards Arabs, and Muslims more generally, to have their devastating consequences. These network technologies continue to be the basis and mainstay of the ‘cyber jihad’ that is able and willing to conduct operations throughout the world. Conversely, these terror attacks by aggrieved Islamic groups have triggered an equally networked response by the Western powers in the form of intelligence sharing and political and military actions. A result of this is that no part of the world has been unaffected by this deadly interaction that takes place in both the virtual and real worlds. And, as a visit to almost any international airport will reveal, governments across the world have legislated against the so-called ‘war on terror’ in ways that can potentially affect everyone. One can argue then that in the case of the September 11 event, the effects of information technologies do indeed reverberate (through networks) across ‘the entire social structure’.

It is necessary to understand in this definition of the information society that it is the computer and computer networks that make globalization technologically possible. As we shall see in chapter 2, ICTs are both the cause and consequence of globalization. Versions and visions of globalization have been described since at least the time of Marx and Engels. However, it is only through information technologies that the prophecy of a truly global economic system has become reality. The theory of a single economic system becoming hegemonic and pervasive through computer logic is only part of the story. Just as ICTs have been the cause and consequence of the convergence of formerly disparate capitalist industries since the 1970s, so too have ICTs enabled the logic of a market-based economy to incorporate and dominate the social, the cultural and the political realms as well – but this is to get ahead of the narrative slightly.

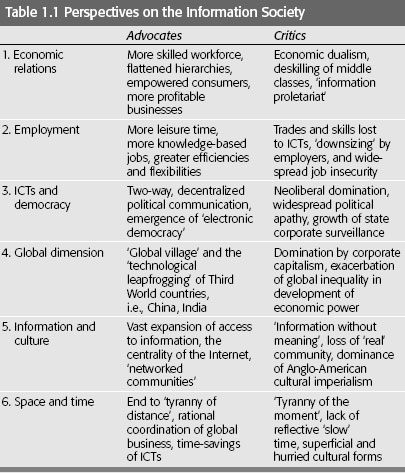

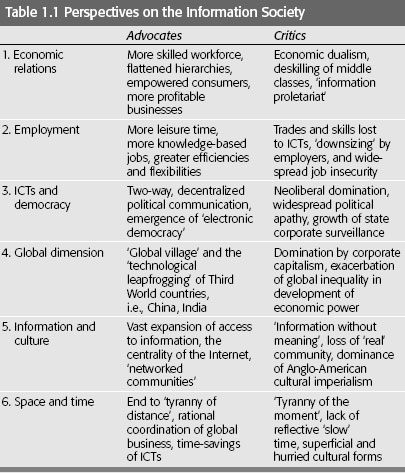

Let us end this brief sketch of what I see to be the primary factors involved in the construction of the information society by pointing to table 1.1, showing a schematic representation of what I have been describing from the perspectives of both advocates and critics of the process. It becomes clear from this table that the perceived effects of ICTs go deep and wide, and that interpretations of these are commonly expressed at both ends of the spectrum: the dream and the nightmare scenario, so to speak.

To take point 1 of table 1.1 as an example: in the 1970s, it was widely predicted by the advocates of new information technologies that the class-based strife that had plagued capitalism would be greatly reduced in the new economic order of post-Fordism. ‘Knowledge workers’ would be more autonomous and more empowered by ICTs, and as consumers they would be more able to negotiate the evolving information systems and structures that they themselves would be helping to construct. The old dualities of capital and labour, of bosses and workers, would be flattened out in a new approach to work and to economic relations. The highly influential business commentator Peter Drucker envisaged such a scenario when he wrote that:

The leading social groups of the knowledge society will be the ‘knowledge workers’ – knowledge executives who know how to allocate knowledge to productive use; knowledge professionals; knowledge employees. Practically all these knowledge people will be employed in organizations. Yet unlike the employees under capitalism they both own the ‘means of production’ and the ‘tools of production’ – the former through their pension funds which are rapidly emerging in all the developed countries as the only real owners, the latter because knowledge workers own their knowledge and take it with them whereever they go. (Drucker, 1993: 7)

Source: Adapted from Lyon (1988) and Flew (2003)

If there is any agreement on the nature of the information society, it would probably be that constant and accelerating change is what characterizes it most of all. Now, how do we see

Drucker’s comments from the perspective of hindsight? Does the passage of time vindicate his generally positive ideas, or does it lend credence to the more critical approach? Well, there is no doubt that many knowledge workers have indeed been ‘empowered’. But it depends upon what kind of knowledge worker and what kinds of knowledge he or she possesses. For example, there is strong empirical evidence that suggests that the most powerful and world-shaping form of knowledge in the information society is financial information. It is digital information and is stored, shared, created, hidden and proliferated through computers. It is a process that has been termed ‘financialization’ and it closely follows the logic of ubiquitous computing in that, as Robin Blackburn notes:

It [financialization] permeates everyday life, with more products that arise for the commodification of the life course such as student debt or personal pensions, as well as the marketing of credit cards or the arrangement of mortgages. The individual is encouraged to think of himself or herself as a two-legged cost and profit centre, with financial concerns anxious to help them manage their income and outgoings, the debts and credit, by supplying their services and selling them their products. (2006: 39)

For most of us, the financialization of everyday life is something that happens to us. However, knowledge workers with the kind of expertise that makes this process happen are able to develop profoundly valuable knowledge that shapes the parameters of change in the globalized and networked economy. These are Drucker’s ‘knowledge executives’, whom he distinguishes from your average computer programmer, university academic or administration worker. Such workers have grown from a virtually negligible number in the 1970s and 1980s to become a significant stratum in global business. These are the entrepreneurs who have used their ideas and their expertise – alongside another new economy instrument, ‘venture capitalism’ – to become powerful and wealthy in the information society. They work feverishly in the context of the acceleration of information flows, where the trick is to know when is the ‘right’ time to buy, share, create or produce information. The fact that ‘timely’ access to knowledge and the ability to manipulate it is a key function for success in the information society is reflected in the research of the business community itself. In 2005, for example, Merrill Lynch reported that the number of high-net-worth individuals (HNWIs) – people having a net worth of at least US $1 million, excluding their primary residence – increased by 7.3 per cent to 8.3 million, an overall increase of 600,000 worldwide over the 2004–5 period (Merrill Lynch, 2005). Economic growth and market capitalization (that is, the size of a corporation measured as a reflection of its stock price) have been identified in the report as the main drivers of this wealth increase. Stock prices, especially, are crucial in the high-speed information society, and can be said, indeed, to be the main factor deciding whether the global economy grows or not. And what drives the stock market is knowledge and information. To have primary access to the kinds of information that determine stocks and shares, to be able to use this within a select community of ‘knowledge executives’ in business, and be able to transfer this knowledge and information into ‘new’ forms of knowledge that can then be sold, is to be on the inside track of the information economy.

To this extent Drucker has been proved correct. But there are other realities that stem from what these people do with their privileged knowledge. Consider the blithe reference to ‘pension funds’ as the ‘real owners’ of the ‘means of production’. Consider it in the context of the idea that pension funds and the growth in importance of the finance (financialization) process in general have been the economic power behind what Robert Boyer (2000) has termed a ‘finance-led post-Fordism’. And consider now that the financial markets, as drivers of the world economy, are exceptionally volatile and inherently unstable (Stiglitz, 2002). Indeed, the collapse of the now-notorious (and ironically named) Long-Term Capital Management (LTCM) was evidence of how immense crashes of ‘virtual’ corporations affect the real lives of millions of people as they take their savings and pensions with them into liquidation. LTCM began trading in 1994 and had a Board of Directors stuffed with clever people such as Myron Scholes and Robert C. Merton, who shared the 1997 Nobel Prize for Economics. It vaporized as a business entity in 1998 after losing 4.6 billion dollars in the space of four months (Mackenzie, 2006). Then of course there is the Enron Corporation, ‘a case study in financialization’ which was another virtual, knowledge- and information-based entity named as ‘America’s Most Innovative Company’ by Fortune magazine. Enron crashed and burned, taking with it into oblivion the savings of its investors, amounting to some 62 billion dollars, and ending the employment of over 20,000 individuals (Fox, 2003: 2–4; Froud and Williams, 2003).

This typifies the argument that Drucker’s ‘real owners’ are in fact wheelers and dealers in what Susan Strange (1986) called ‘casino capitalism’. They have no real sense of control, or power, or autonomy in the way that this influential champion of the capitalist, globalized and networked system envisages. Seen in a more critical perspective, these ‘knowledge executives’ may be argued to create little that is tangible or enduring. They stand on permanently shifting sands that threaten to envelop those whose money they use when either the numbers no longer look good to the market, or when the market’s inherent volatility simply overcomes them – usually for reasons they did not anticipate, despite their knowledge and expertise.

It is these kinds of questions and these kinds of contrasts, within the context of an accelerating information society, that much of the rest of the book will be taken up with. The intent is that the dreams and nightmares of our digital world can become part of a rational and coherent narrative that makes sense of the seeming chaos and apparent unpredictability of life that can earn the individual billions or bring low a major corporation. A framework of temporality which these dreams and nightmares can be set against is, of course, no solution. Indeed, it does not even presume to supply answers to the questions posited. What this book will provide, though, is a selection of pathways to further questions, to a wider literature that brings the horizons of understanding rather nearer to hand. Whether you see this world to be comprised of cyber dreams or digital nightmares (or a bit of both) is up to you. However, I think it unarguable that the information society is a world where collective and personal autonomy, in any real and abiding sense, has been gradually diminishing in the wake of an accelerating economy, culture and society that we can barely keep up with. This is my particular bias. I also think that reading and reflective thinking are ways to exert control over time, to slow down the ‘constant present’ (Purser, 2000) and lead to forms of understanding – power and knowledge of a specifically political kind – that can act as the basis for agency in the real world.