In Chicago, Bethel Commercial Center includes retail space, offices, a bank, and a daycare center.

ALAN SHORTALL PHOTOGRAPHY

Aside from the location and configuration of the site, the keys to success for small developers are the quality of their development team and their access to capital. Small developers can often use the same professional consultants as larger firms, buying not just expertise but credibility in the marketplace by affiliation. Even experienced developers, moving into new markets or product types, will often find that appropriate local consultants, or firms experienced with the particular product, can mitigate their risk in pursuing innovative projects.

More fundamentally, the cyclical history of real estate development has proved repeatedly that a lean central organization is a key to surviving downturns. One way to maintain a small, lean organization is to use consultants for noncore and project-related tasks. To select a consultant who will enhance the team, find the best person or company available, even if it costs a little more (when price must drive the decision, spend first on the knowledge areas furthest from your own internal expertise); be certain that the person or company has direct experience with the particular type of product under consideration; consider the prospective consultant’s strategic value beyond the project at hand; look for people and firms that add value beyond their core competence: an engineer, for example, who might have productive relationships with planning staff; beware of firms that depend completely on one, or a few, clients; select people who are familiar with local conditions, who have worked constructively with the anticipated approval authorities; and solicit other developers’ opinions on consultants in the area.

Finding the best team for the job can take time. From the day they start in business, beginners should assemble names of prospective consultants and interview them. Development often follows a “hurry up and wait” pattern, and slow times between tasks are a great time to periodically extend the developer’s network. Assembling a team from scratch is difficult; more experienced developers have already established a network of consultants, contractors, and professionals, and building a permanent team takes more than one project. Nonetheless, the time and effort spent in finding the best possible team are a good investment. Developers can spend as much time in search of relationships as they do in seeking investment capital.

Even more important than the assembly of the team is the structuring of the development or operating partnership. The result of a hastily assembled partnership can be heartache and financial risk. The safest partnerships are those in which the partners have come to know each other through a long history of working together. Over time, the partners can understand each other’s strengths and develop confidence in their associates’ integrity. Beginning developers, of course, seldom have such historical relationships, though they may have some. The beginner must remedy this limitation by making good strategic partnership choices and being diligent in the legal structuring of the development entity.

Partnerships are frequently formed around specific projects, and developers might have different sets of partners for each of several projects. Partnership arrangement can evolve over time. Early deals might involve several partners, each filling a major function, like financing or construction. In subsequent deals, the number of partners might diminish as the developer learns how to obtain the needed expertise without sharing project equity.

Landowners are often partners in a beginner’s early projects. Even if the landowner is not able to contribute critical analytical or management skills, his or her involvement can be very valuable. Landowners may contribute their property as equity—always scarce for the beginning developer—but they might also supply debt, via seller financing, at terms unavailable through financial institutions. Even if they do not materially participate, landowners can tie up land while financing and approvals are obtained. In income property, key tenants might also be offered partnerships to induce them to lease space in the project, particularly if the project can be designed around the tenant’s specific needs. Both landowners and tenants, however, generally view real estate as a noncore activity, for which they will tolerate little risk.

A common mistake in forming partnerships is to choose partners with similar rather than complementary skills. Typical complementary pairings include capital and development experience or construction and management experience. Whatever the match, partnerships work best when everyone shares equitably in risks and returns and is equally able to cover potential losses. In most partnerships, however, one person is wealthier than the others and will understandably be concerned about ending up with greater risk, even if the partnership agreement allocates this burden equally. This concern may be overcome in several ways, beginning with the concerned partner’s selection of an appropriate liability-limiting structure, before entering the partnership. Within the partnership agreement, the capital partner may also specify that a partner who is unable to advance the necessary share of capital will lose his or her interest, and from the beginning the wealthier partner can be given more of the return, or less of the management workload, to compensate for greater potential liability.

Hudson Green, a 48-story mixed-use complex in Jersey City, New Jersey, was developed by a partnership between Equity Residential and K. Hovnanian.

ALAN SCHINDLER PHOTOGRAPHY

A major source of problems in partnerships, especially general partnerships in which everyone has equal interests, is uneven distribution of the workload, or inadequate compensation for partners handling the day-to-day work of creating and implementing a project or projects. Successful developers think of compensation primarily in terms of incentive, rather than fairness. Key areas of responsibility must be determined in advance, and types of compensation should be defined appropriately to incentivize each. For example, one partner might receive a greater share of the development fee, with another receiving more of the leasing fee. To save cash, it might be preferable to accrue fees rather than to pay them as earned, so long as funding is adequate to meet expenses and provide a “living wage” and tax distributions to the working partners.

Even if accrued compensation is not part of the initial deal, variation in cash flow may require timing adjustments. Accounting for partners’ interests in a “capital account” is good practice, offering an ongoing check on the appropriate equity investment of each partner and allowing management to address imbalances at distributions or capital calls.

Partnerships can last for years, so the choice of partners is critical. Large developers that bring in less experienced partners for specific deals generally enjoy a rather one-sided partnership, ensuring them management control; beginning developers, however, do not have the same negotiating power and must carefully weigh each additional partner who dilutes their potential equity interest and management flexibility.

Working out the partnership arrangement in advance, with legal advice, is essential for anticipating and avoiding conflict. A written agreement that defines each partner’s role, responsibilities, cash contributions, tax needs, and share of liabilities and that sets out criteria for the dissolution or modification of the partnership is an essential document. Many members of general partnerships formed casually and on the basis of verbal assurances have been shocked to discover that they are liable for their partners’ debts unrelated to the partnership’s purposes. In fact, those types of liabilities are often the default condition of a general partnership constructed without good legal advice.

The most basic approach to a partnership combines someone with extensive development experience and someone whose credit is sufficient to obtain financing. The financial partner should have net worth at least equal to the total cost of the project under consideration, and preferably twice that amount. Some banks might require a higher multiple or specific collateralization of the loan. If the partnership does not include someone with sufficient credit, then the partners will have to find someone to play that role before they can proceed. Other developers, high-net-worth individuals or syndicates of these investors, or family and friends may be promising candidates for beginners without access to institutional capital.

Bringing in any financial partner before the full requirements for cash equity and the amount of net worth are known is a mistake. If, for example, the financial partner is to provide the necessary financial statement and, say, $800,000 cash equity for 50 percent of the deal, the developer may be required to give up an unnecessarily high portion of ownership if he later finds that an additional $100,000 cash equity is needed. On the other hand, with no financial partner waiting in the wings, a prospective lender could lose interest while the developer is locating one. The ideal situation is to line up one or more prospects in advance, with a general understanding of the types of projects being pursued and a commitment to invest if certain criteria can be met by a deal, in a particular time frame.

Development is always a team effort. A development team can be assembled in one of several ways. At one extreme, a large company might include many services, from architecture to construction management and leasing. The advantages of a robust organization are obvious: at each phase of development, critical services are performed in house, presumably with better quality control and coordination than outside vendors would offer. Additionally, each ancillary business can become a profit center for the firm, as principals find themselves asking, “Why give the broker that 6 percent?”

Developers must, however, be careful of “mission creep” into activities too far from the core competence of the principals. More common is the other end of the spectrum: a development company might consist of one or two principals and a few staff members who hire or contract with other companies and professionals for each service as needed. Although requiring more contract management and external communication, the advantages of a lean organization are substantial. This lesson is learned at every market downturn, when firms that are able to shed overhead quickly can extend their viability with low or no operating income. Limiting the “burn rate” of the development firm is good practice in a strong market, and it becomes an essential survival skill in a serious downturn.

From the perspective of organization, development can be a low-cost business that is relatively easy to enter, assuming one has the credibility and relationships needed to access investment capital. A development company can be started by just one person, with little investment in equipment or supplies beyond an office. Small developers are often able to compete effectively against larger organizations, using technology and consultants to leverage the capabilities of the principals. Although larger developers might obtain better prices in some areas and will certainly have easier access to money, they also tend to have higher overhead expenses and are usually slow to respond to market changes.

Like most enterprises, development firms typically pass through three stages—startup, growth, and maturity—and each stage is characterized by distinct risks and opportunities.

STARTUP. Startup is characterized by work toward two short-term goals—successfully completing the first few projects and establishing consistent sources of revenue to cover overhead. During this stage, firms are more likely to be merchant builders, selling their projects after they have been completed and leased, rather than investment builders, holding them for long-term investment. “During the startup period, the developer’s entrepreneurial skills are the critical ingredient. The developer has to develop contacts—with investors, lenders, political leaders and staff, investment bankers, major tenants, architects, engineers, and other consultants. Eternal optimism and the ability to withstand rejection are essential.”1

A common startup pitfall is overexpansion before the company has developed the staff and procedures to handle greater activity and new types of business. When tenants or buyers sense that a developer is not responding to their needs quickly enough, that developer’s reputation is likely to suffer. The growing developer must build staff and establish procedures for accounting, payable and receivable processing, leasing, tenant complaints, reporting functions to investors and lenders, construction administration, property management, and project control. Successful developers know that accountability is just as important for functions handled by consultants as it is for in-house services. A related mistake is hiring too many people too quickly. A startup business seldom has enough cash to pursue every line of business, and those that watch the overhead closely during startup tend to fare better than those whose first priority is projecting a high-profile image. Some of the most successful developers have built thousands of apartment units and millions of square feet of industrial and office space with a professional staff of only three or four, contracting with consultants for virtually everything. Although homebuilders operating this way can suffer a reputation as a “briefcase contractor,” the developer role is already one of entrepreneurial coordination, and limited in-house capabilities are seldom marks against the firm’s reputation, if the principals’ standards of integrity and professionalism are consistently upheld.

GROWTH. A firm in the growth stage has achieved a measure of success. It has instituted procedures for running the business and has assembled a team of players to cover all the major development tasks. It is beyond the point at which a single mistake on a single project can lead to bankruptcy. This firm is in a position to make strategic decisions about its future: what kinds of projects will be pursued, in what markets, with what sort of capital structure?

Maintaining the mission and entrepreneurial energy of the founders and inculcating that spirit into new team members are always challenges for growing firms. The firm must implement controls and procedures, without bureaucratic sclerosis. Development at any scale requires quick decisions. The key is to maintain direct involvement of the firm’s principals through this growth phase. Adding capacity and processes must always be considered as a way to leverage principals’ time, rather than as a replacement for their judgment and expertise.

Employees who are used to the freewheeling atmosphere of a startup organization sometimes resist the increased level of oversight by senior management; thus, in the growth phase, a firm may find itself with a new problem: retention of key players. The firm must maintain an entrepreneurial environment that motivates qualified, aggressive people. A one-person firm succeeds because that one person accepts risk and controls every aspect of the process. But when staff becomes necessary to handle the workload, the transition from one-person leadership to greater hierarchy can be difficult. Not only must the right staff be in place, but the founders must also be able to delegate.2

The right staff for a startup organization is not necessarily right for an organization in the growth phase. Many development firms are, at least at the beginning, family businesses. The difficult transition in this case is often generational. Family dynamics can complicate the transfer of management control, and, even after the transfer, the founding parent may remain in the background, giving directions that may not match the firm’s current model. Many firms never make it through this transition.

Conflict can also arise in family firms when the second generation is eager to take risks and try new projects at a time when the founding generation is becoming more risk averse. If the founding generation cannot find a way to let the second generation pursue its goals or have a chance to fail, the younger generation may leave the firm, at least for a time. Recognizing this dynamic, some developer-parents insist that their children work elsewhere before they join the family firm. This strategy offers the additional benefit of making principals in the firm aware of benchmarks and best practices in other organizations. Often, family-controlled development companies skip a generation; the second generation leaves the business to work elsewhere while the third generation enters the business. Wise managers plan ahead for problems, recognizing their children’s needs to achieve success on their own and understanding their forebears’ needs as stakeholders.

MATURITY. Firms reach maturity after they have established a track record of successful projects and have built an organization to handle them. Mature development companies have built a network of relations with financial, political, and professional players and have cash flow and assets that confer staying power, the so-called deep pockets. These firms tend to focus on larger, more sophisticated projects that tend to be more profitable and that require fewer managers than multiple smaller, less predictable projects. With higher barriers to entry, they usually face less competition.

Mature firms are more averse to risk, and their managers want to fully comprehend and mitigate the risks that they take. They have often built up a large net worth that the owners want to protect. They do not need to assume as much risk as they did previously, as lenders and equity investors are eager to participate with them. Developers can often reduce or avoid personal liability on notes, and financial partners are willing to assume more financial risk in return for an equity position in the project.

Several characteristics are typical of mature firms, regardless of their size, organization, and style of management:

• They know how to manage market risk, particularly in overbuilt markets.

• They have distributed authority and responsibility within the firm.

• They can evaluate the firm’s effectiveness and efficiency.

• Most important, they can attract, challenge, compensate, and retain good people.

Wolverton Park in Milton Keynes, United Kingdom, is a redevelopment of a former railroad engineering works. Today, the mixed-use development includes office, residential, retail, and more than 400 parking spaces.

During startup, organizational structure is less an issue than it is during growth and maturity. In the early years, most developers resist formalized organizations. Everyone reports directly to the owner, who makes all the major decisions. As firms grow, the delegation of authority, especially in financially sensitive areas, becomes essential because the owner’s time and availability are limited. Sometimes, an outside consultant or new CEO is needed to instigate necessary change.

In most firms, the principals control the same few decisions: site acquisition, financing arrangements and major leases, and timing and terms of the sale of a project. A common practice among even very large firms is for the principals to retain the responsibility for making deals, initiating and maintaining strategic relationships, hiring and compensation, the activities most reliant on personal contacts, reputation, and understanding of the firm’s strategy, while tactical responsibilities may be delegated.

Development firms are organized by function (that is., construction, sales), by project, or by some combination of the two. Smaller firms are more often organized by project, larger ones by function. That is, owners of small firms tend to appoint one individual to be in charge of each project, with the group working on that project responsible for all aspects of it—financing, construction, marketing, leasing, and general management. In large firms, on the other hand, one group is responsible for each key function across all projects.3 In some organizations, employees report to two different managers, one responsible for function and the other for geographic area or product line. Increasingly, firms use a hybrid model, where partners, who may represent expertise in leasing, construction, or deal structure, each take on direct responsibility for general management of a project, drawing in the other partners on project tasks where their expertise falls short. A firm’s organizational structure often reflects how it has grown and evolved over time. Some of the largest firms maintain a project-manager structure because they have grown by giving partners responsibility for specific geographic areas, product types, or both. Regardless of where firms begin, structure should be evaluated periodically as the firm grows, to maintain partners’ comfort with the framework as their responsibilities change.

Manager compensation is a major issue facing owners who want to align employees with the firm mission. One answer is to give key individuals equity in the firm. According to John O’Donnell, chair of the O’Donnell Group in Newport Beach, California, “The reason you give employees equity is you can’t pay them what they would command on the open market. Instead, you give them a stake in the future.” For senior executives, this might be true partnership equity, whereas key personnel at the project level might receive phantom equity.

Computed from firm or project profits like a bonus, phantom equity is an incentive for project managers, encouraging them to think like entrepreneur-owners. Unlike real equity, however, the individual does not legally own an interest in the project and is not liable for capital contributions. The project manager’s signature is therefore not required for transactions, which is important because junior staff turnover is not uncommon in this cyclical business. Also, if a partnership includes more than one property, phantom equity in the firm avoids the accounting difficulty of project-specific interest, which may complicate operating agreements or joint ventures. O’Donnell’s firm measures the performance of each property each year and contributes the appropriate share of the manager’s profit to a phantom equity account. If, for example, the property makes $100,000 and the manager has a 5 percent interest in it, the account is credited $5,000. If the property loses $100,000, the employee does not have to cover his share of the loss out of pocket, but paper losses accrue to the account and must be “repaid” before future profits are distributed. In this way, the employee does not have to worry about raising cash to cover potential liabilities but participates materially in both the upside and downside potential of the business.

Many firms provide for a period of five to ten years before an employee’s phantom equity becomes vested. O’Donnell’s firm, for example, might give an employee 2.5 percent of a project after three to five years of employment. Each year after the employee becomes vested, he or she receives an additional 0.5 percent, up to a limit of 5 percent. If a vested employee leaves the company, O’Donnell retains the right to buy out that person’s interest at any time based on a current appraisal of the property and he retains the right to select the appraiser. If someone leaves the company without notice, he might buy out that employee’s interest immediately. On the other hand, a longtime secretary who leaves to start a family or a manager who gives advance notice (say, three months) might receive profit distributions for years, thus enjoying the project’s potential to the extent that his or her tenure vested these rights.

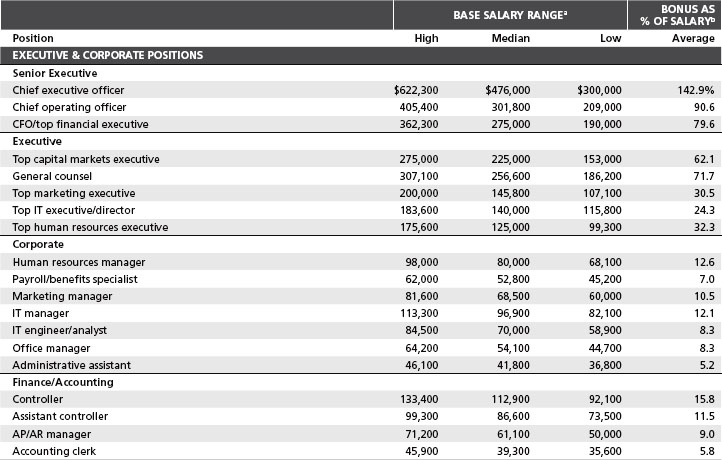

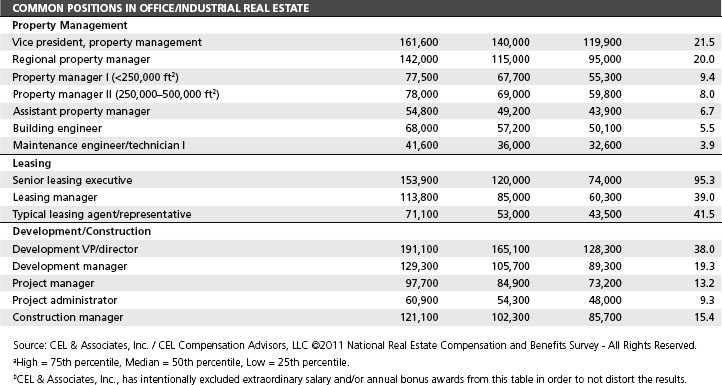

FIGURE 2-1 | National Real Estate Compensation Survey, 2011

No formula exists for determining how much equity a developer should give away to attract top managers. Beginning developers may have to pay experienced project managers 25 percent of a project’s profits, whereas established developers may need to pay only 1 to 5 percent. Employees’ risks are lower with a more established developer, so their shares of the profits are lower. One major developer, for example, has three levels of participation, which are given not as rewards but as career paths. The lowest level is principal. Project managers who are star performers are eligible. They receive up to 10 percent (5 to 7.5 percent is typical) of a project in the form of phantom equity. The next level is profit and loss (P&L) manager, someone in charge of a city or county area. P&L managers are responsible for several projects and principals; they receive 15 to 20 percent of the profits from their areas. Their interest is also in the form of phantom equity. The top level is general partner, reserved for managers of a region, state, or several states. General partners receive real equity, are authorized to sign documents on the firm’s behalf, and incur full risk.

Real estate is a cyclical business; in each downturn, a substantial portion of capable junior and middle managers leave the industry. As a result, even in relatively weak markets, the most experienced professionals can be in relatively short supply. Firms respond with creative and highly motivating compensation packages to attract and, more importantly, to retain these experienced hires. Compensation for top performers is usually paid through bonuses rather than salary and can range from 10 percent of salary, at the project level, to well over 100 percent for executives.

Strategic Planning and Thinking: Planning the Business

EVALUATE THE PRESENT SITUATION.

• What are the company’s accomplishments? How do they compare with previous goals?

• Where is the company headed? How should it get there?

• What are the owner’s or founder’s interests and expectations?

• What is the external environment?

• Market changes and trends

• Changes affecting products and services

• Opportunities from changes

• New and old risks and rewards

• Political environment

• Who are key competitors? Where do they excel?

ANALYZE THE COMPANY’S STRENGTHS AND WEAKNESSES.

• What properties has it developed, bought, marketed? How successful have they been?

• How has the firm done in the past?

• Management capabilities

• Threats

• Opportunities

• What past decisions would be changed?

SPECIFY GOALS FOR THE STRATEGIC PLAN.

• What is the financial strategy?

• What is the firm’s strategy regarding products?

• Quality

• Investor or merchant builder

• Does the company need to diversify its product?

• Does the company need to diversify its location?

• What is the company’s strategy regarding land?

• Land banking versus carrying land in slow times

• Developed land versus raw land

• What is the marketing strategy?

• What is the strategy regarding production and construction?

• How does the company get the job done?

• What is its management and organizational strategy?

SPECIFY AN ACTION PLAN—PROGRAMS, STEPS, OR TASKS TO BE CARRIED OUT—CONCERNING RISK, REWARD, AND REALITY.

• What activities is the company engaged in now?

• What is the state of financial planning?

• Where do equity and debt come from?

• Are changes expected?

• How strong are financial suppliers?

• What will be its financial needs in the next 24 months, the next 36 months, or longer to meet strategic goals?

• What are the company’s objectives? What metrics is it committed to achieve?

• How strong will lines of communication and internal controls be for

• Financial results

• Acquisition and development

• Operations: property management, leasing, tenant improvements, customer relations

• Controls and measurement

• Responsibilities and budgets

Source: Sanford Goodkin, president/CEO, Sanford R. Goodkin & Associates, San Diego.

Personnel costs are typically 60 to 80 percent of most operating budgets, and they are the most critical component of a management or operating company. Benefit costs, especially for health care, continue to rise, and as in every industry, managers are increasingly sharing these increases with employees. Even before the financial crisis of 2008–2009, many firms were also downsizing, and the uncertainty and cash flow disruption of the past few years have made many managers consider the benefits of a lean payroll. The lean organization will use more outside contractors to fill interim needs. “They just can’t afford to pay everyone market rates [for high-end people] every day, all the time,” says Chris Lee, president of CEL & Associates in California.

Most beginning developers—and even many large ones—do not have a formal strategic plan. Rather, they may focus on a specific demographic market, or a neighborhood, or a property type, but within these parameters the firm will respond to opportunities as they arise. In this way, developers build expertise and a track record of success, and more opportunities tend to arise within a well-chosen market. Organically, the firm’s competence can become its business strategy.

As firms gain maturity, size, and diversity, they may benefit from more formal strategic planning. A strategic plan gives junior team members a sense of the direction of the business and gives them direction on how to contribute at the deal or project level. The effect of a good strategic plan, then, can be counterintuitive: encouraging more decentralization of the day-to-day activity of the firm. The plan should include budgets, a master schedule tied to the budget, and systems for approving and tracking projects. The accompanying feature box summarizes the major issues that strategic planning should address. Just as important is to include the assumptions, identified trends, and external dynamics that underpin elements of the strategy, so that they may be reevaluated in future revisions of the plan.

The strategic plan helps the company achieve its objectives faster, because everyone understands the firm’s immediate goals and longer-term objectives. Such plans are most effective when prepared with broad participation and when the resulting strategy flows into clearly defined tasks. Whereas the business plan is strategic, the budget is tactical; that is, the budget lays out the specific approach that will be used to follow the broad strategy of the plan. The strategic plan culminates in an action plan, which should establish specific protocols for managers to follow—for example, policies for evaluating the competition and an area’s long-term economic outlook, or for evaluating individual deals, contractors, or joint ventures against the criteria of the strategic plan.

Assembling a team of professionals to address the economic, physical, and political issues inherent in a complex development project is critical. A developer’s success depends on the ability to coordinate the completion of a series of interrelated activities efficiently and at the appropriate time.

The development process requires the skills of many professionals: architects, landscape architects, and site planners to address project design; market consultants and brokers to determine demand and a project’s economics; multiple attorneys to handle agreements and government approvals; environmental consultants and soils engineers to analyze a site’s physical and regulatory limitations; surveyors and title companies to provide legal descriptions of a property; contractors to supervise construction; and lenders to provide financing.

Even the most seasoned developer finds that staying on top of all of a project’s technical details is difficult. For beginners, a key is to find consultants and partners who can help guide the development process, as well as provide technical knowledge. Regardless of experience, most developers can benefit from continuing investment in their own training, and in updated software and communications tools to leverage their personal project management abilities. Developers may find small subcontractors lack technologies and communications tools—even e-mail. Working with these firms may present continuing difficulties.

To begin the search for a consultant with particular expertise, developers should first seek the advice of successful local developers who have completed projects similar to the one under consideration. They should ask experienced developers about the consultants they use and their level of satisfaction with the consultants’ work. Beginners should also remember, however, that established developers may consider newcomers the competition, and it may take some time to build the trust necessary for a frank exchange of opinions. Beginning developers might take advantage of networking opportunities by joining associations of local developers or national organizations geared toward the real estate product of interest, be it residential, shopping centers, or business parks. The key is to be active in such organizations by serving on committees and participating in events.

Developers should obtain a list of the consultants whose work has impressed public officials and their planning staffs. Staff is often prohibited from recommending professional service firms, but usually at least an informal opinion for or against a specific firm can be obtained. Certain approvals might hinge on the reputations of specific team members; indeed, part of consultants’ value could lie in the connections they maintain with the public sector. Because governments have pulled back from some services, relying on certifications of outside professionals, many tasks that were once performed by public servants may now be performed in the private sector by the very same people. A common example is soil evaluation, a function of departments of public health, which is commonly performed by “authorized evaluators,” who are typically former department employees who retain both the knowledge of their field and relationships with the approving agency.

Associations of architects, planners, and other development-associated professionals are another source of potential consultants. Such organizations usually maintain rosters of members, which are useful as a screening tool because most professional and technical organizations have defined certain standards for their members. Those standards might include a certain level of education and practical experience, as well as a proficiency examination. Most associations publish trade magazines that provide a wealth of information about the field and are often available online.

Strategies for selecting consultants vary according to the type of consultant being sought. The most common approach is a series of personal interviews. Beginners should not hesitate to reveal their inexperience with the issues being addressed or to ask potential consultants to explain clearly their duties and the process of working together. Consultants will profit by dealing with a developer, so they should be expected to take the time to explain the fundamentals.

A proper interview should address the developer’s concerns regarding experience and attitudes. The developer should look for a consultant with experience in developing similar projects. An architect or market consultant who has concentrated on single-family residential development would be inappropriate for a developer interested in an office or retail project.

The developer must be sure to ask for references and then must contact those references personally to learn about the consultant’s quality of work and business conduct, ability to deliver on time and within budget, interest in innovation, tolerance for clients’ direction, and professional integrity.

The developer may also inspect some of the consultant’s work—marketing or environmental reports, plans and drawings, and finished projects. The developer should be comfortable with the design philosophy of a prospective member of the creative team and satisfied with the technological competence of a potential analytical consultant.

The developer must be certain that the chosen firm has the personnel and facilities available to take on the assignment. This balance is difficult to achieve because the developer is likely to be attracted to small firms’ personal attention to his needs, while being sensibly wary of involvement with an organization without capacity or staying power. If a consultant appears to be struggling to keep up with current responsibilities, the proposed project is likely to suffer from neglect. A good rule of thumb is that the proposed project should represent no more than a third of the consultant’s overall business.

Having ascertained the overall fitness of the consulting group, the developer should establish who will be the project’s manager and request a meeting with that person and then examine several projects for which that manager was responsible. Beginning developers are often reluctant to involve themselves in “other people’s business,” but it is not inappropriate to ask that specific personnel and time allocations be delineated in the professional services agreement. Toward that end, the developer is well advised to find out what subconsultants the firm would be likely to hire, and how the scope of work will make each sub accountable to the project timeline and performance standards. It may be possible to speak with key subconsultants as well, to map out a plan for completing the assignment together. Successfully accomplishing the assignment will require coordination between the consultant and its subs, and the client who will be dependent on these individuals should know who will be responsible for what.

Hiring a firm is a two-way street. While the developer is sizing up the consultant, a similar process is going on across the table. Displaying a positive attitude about the project and the consultant’s potential contributions is important. A beginning developer should not be offended when the consultant asks about his experience and competence to complete a development project, the existence of adequate financial resources and accounting capacity to pay the bills, the feasibility of the proposal, the ability to make timely decisions, and what might happen if the project is delayed or aborted.

Consultants need to be confident about a developer’s ability to meet obligations and should know when they are working “at their own risk.” This last consideration has become especially important over the last few years, as cash flow difficulties for developers and owners of real estate have trickled down into crises at firms offering development services. An experienced consultant will appreciate an open and honest conversation about when work will be compensated, and some caution in releasing work for future projects.

Finally, the developer should judge whether he has established a rapport with the people being considered during the preliminary interview. The ability to get along with these people is essential for the project’s completion, so if problems arise at this point, the developer should consider whether dealing with them daily is possible. Thinking ahead to the long timeline of some development projects, the developer may wish to consider whether the organization has the same rapport at the junior level as is found at the executive level. Compatibility is a key to the project’s success—and to preserving the developer’s sanity.

If, after checking references, the developer feels uncomfortable with any aspect of the consulting firm, eliminating the firm from further consideration may be the most sensible move. If the developer’s responses are favorable about the firm as a whole but not about the particular person being assigned to the project, he should raise these concerns with the firm’s principals. A larger firm should have another staff person available, but a smaller firm may not. The developer must be assured that the most qualified people will be assigned to the project, that those people will continue to be available until the project is complete, and that the team will leave behind it a legible paper trail for future phases or operating partners to recover the design logic, legal justification, or operational guidelines for decisions made during development.

Who Is Involved, and When, in the Development Process?

SITE SELECTION

• Brokers

• Title companies

• Market consultants

• Transactional attorneys

FEASIBILITY STUDY

• Market consultants

• Economic consultants

• Construction estimators

• Surveyors

• Mortgage brokers and bankers

• Land use attorneys

• Engineers

DESIGN

• Architects

• Land planners/landscape architects

• General contractors/construction managers

• Surveyors

• Soils engineers

• Structural engineers

• Environmental consultants

MARKETING

• Brokers

• Public relations firms

• Advertising agencies

• Graphic designers

• Internet service firms

FINANCING

• Mortgage brokers and bankers

• Construction lenders

• Permanent lenders and syndicators

• Title companies

• Appraisers

CONSTRUCTION

• Architects

• General contractors

• Engineers

• Landscape architects

• Surety companies

• Authorized inspectors

OPERATIONS

• Property managers

• Specialty and amenity maintenance teams

SALE

• Brokers

• Appraisers

THROUGHOUT THE PROCESS

• Attorneys (title, transactional, land use, litigation)

Consultants should willingly quote a fee for their services, presenting a written proposal reflecting the costs for delivery of the desired product. Depending on the particular expertise, this quote may be a simple lump-sum bid, an hourly rate, or a menu of services and associated costs. The developer will benefit from having as much information in writing as possible. Although cost is an important factor, it must be balanced by experience and by the quality of the consultant’s past work. Developers should be careful not to choose simply the lowest price. If detailed proposals are available, developers should compare the proposed budgets to see how the money is allocated and to identify the differences in proposals to judge whether the numbers are reasonable. They should also ensure that the prices include the same types of services. For example, a lower fee could possibly exclude services that will later be required, necessitating future additional charges. A lower quotation might also exclude the amount needed to cover unforeseen incidents. The issue of unforeseen costs is a hazard of the development business, and it is often the case that changes to the scope and cost of services ultimately represent a larger range than the differences in initial quotes. It is therefore essential that any professional services agreement spell out clearly the types of events that could trigger additional costs (inadequate base drawings, new regulatory requirements), the process by which the scope may be changed and the notice required to do so, and the specific unit prices for additional work.

Once a firm has been selected, most developers prefer to employ a fixed-price contract, using the figures quoted in the proposal. Payment can be made in several ways, depending on the nature of the product to be delivered. A schedule could be used to establish milestones, such as the delivery of a specified work product that triggers an agreed-on payment, or developers might find that allowing projections of cash flow to establish a monthly schedule is more advantageous. Smaller jobs might require a lump-sum payment up front.

Some consultants, like lawyers, work according to a time-and-materials (T&M) agreement, with the client billed according to staff members’ hourly rates and the cost of materials used to complete the task. Materials include reimbursable expenses, such as printing or shipping, which may receive a markup for management time. New clients are an unknown for which many consultants will prefer T&M arrangements. T&M agreements are complicated, however, and require constant monitoring to verify the amounts that are being billed and to understand them in relation to the overall project scope. Less experienced developers lack benchmark information about appropriate costs for handling specific tasks, making these agreements inherently risky. When constructing T&M agreements, the client should be clear on a dollar value that may be billed each period without prior approval, so that a casual approval to “take care of that” does not turn into an unanticipated receivable at the end of the month. One experienced construction manager advises, “Regardless of careful construction and monitoring, T&M agreements require trust and common expectations for the work to be performed. Executing these arrangements with strangers is a recipe for administrative headache and hurt feelings.”

Retainer agreements that pay the consultant a flat monthly fee should be avoided because such arrangements can be very costly in the long run. When delays stop work on an aspect of the project for which billing continues apace, not only is cash flow impaired but the incentives of developer and consultant may become warped when 50 percent of the work is completed, but 90 percent of payment has been received. Retainer agreements are usually appropriate only for elements of a project that are truly ongoing, such as public relations management during the lease-up period, or for services that may be thought of more as insurance for eventualities that may occur, such as land use counsel during the development period.

Regardless of the chosen method of compensation, both the developer and the consultant must negotiate a mutually agreeable performance contract. The contract must explicitly list each duty that the consultant is expected to complete. The developer should expect that services not explicitly included in the agreement will probably require future negotiations that will most likely lead to additional costs for the developer. The contract should clearly spell out a schedule for the delivery of services, including a definitive date for delivery of the final product, and expected turnaround for major steps in the process.

After the parties sign the agreement, the working relationship with the consultant begins. The developer must work closely with the consultant to ensure that everything proceeds according to schedule. The development team is made up of a group of players whose tasks are interrelated, and the tardiness or shoddy work of a single firm could set off a chain reaction and cause costly delays.

As the team leader, the developer must ensure that each consultant is provided with accurate information and that information produced by one consultant is relayed to the others. Any changes in the project’s concept should be communicated immediately. The developer must be sensitive to the effect that changes in the project will have on the consultants’ collective analysis; sudden change could alter requirements for the design, environmental analyses, and parking, for example. Any alterations could be costly, as consultants might demand extra compensation to address the changing elements of the project. It is advisable that the developer begin due diligence and have some idea of the project’s viability before spending significant funds on designers.

A healthy working relationship with consultants is vital. Developers should contribute information and ask questions throughout the process but should also show a willingness to accept consultants’ ideas. Good consultants can decrease development costs and improve a project’s marketability.

A developer must have the management skill necessary to coordinate consultants’ efforts while ensuring that all parties respect the developer’s ultimate authority to make decisions. Problems can also occur, however, when a developer’s ego gets in the way of good advice. A good developer knows when to listen to and accept the advice of others.

The design/construction team includes an array of consultants and contractors who perform tasks ranging from site analysis and planning to cost estimating, building design, and construction management. The work that they perform and/or manage represents the bulk of the project’s total soft costs, and effectively managing their contributions is critical to the success of the development project.

Both beginning and experienced developers depend on architects for advice and guidance. Some developers appoint the architect to head the design portion of a project, and sometimes the construction period as well. Most developers, however, prefer to be their own team leaders, both to maximize their influence on the design and to expedite time-critical processes. Beyond building and site design expertise, architects usually offer extensive experience with the regulatory and physical constraints placed on development and are a valuable asset in communicating with other consultants and in coordinating design with construction processes.

Jamestown Properties converted Warehouse Row, a redevelopment of 19th-century warehouses in Chattanooga, Tennessee, into an urban, mixed-use project with restaurants, boutiques, offices, and event space.

JAMESTOWN PROPERTIES

The search for an architect must be thorough. Only those firms and individuals whose experience is compatible with the proposed project should be considered. It is crucial that the architect be focused on delivering a workable product at a reasonable cost. Those more used to designing high-end custom homes where cost is not an issue may not be suitable for a development of production homes. Beginning developers especially may lean on the project experience of the architect, and an inexperienced architect is likely a better match for a more seasoned client. The developer should always check a firm’s credentials and ensure licensure in the state where the project will be built; building departments require the stamp of a state-admitted architect.

The developer and the architect must share a common philosophy of design, though the developer will often benefit from the broader experience of a design professional, and the developer must feel comfortable with the architect selected. A good architect respects the developer’s opinions and can work through disagreements. At the same time, the developer must consider every decision but respect the architect’s knowledge and experience. Some developers prefer to hire an architect whose work has withstood the test of time; others look for an architect known for innovative designs that make a distinctive statement and may give the developer a competitive advantage or a benefit in public relations or approvals.

When the developer has found an architect, the next step is to reach a written agreement. A set of standard contracts provided by the American Institute of Architects (AIA) provides the basis for defining the relationship between developer and architect. AIA Document B101, Standard Form of Agreement between Owner and Architect, clearly outlines the architect’s duties in the development process and is widely used in real estate development. Developers should remember, however, that this agreement was written from architects’ perspective and seeks to protect their interests.4 In some circumstances, modifications to the AIA agreement form are appropriate, although both parties should be aware that a body of opinion and case law exists for interpreting this standard document, and changes may introduce uncertainty in interpretation of additional terms.

Sometimes, architects are given responsibility for all facets of the project’s design, as well as selecting and supervising land planners, landscape architects, engineers (except survey, soils, and environmental engineers), and parking and other programmatic consultants, as well as all facets of the project’s design. Few experienced developers recommend this practice, however, and some prefer to maintain every subdiscipline in direct contractual relationship with the developer/owner, to maintain long-term accountability to the project and to better understand and manage cost.

The design phase lasts from the creation of the initial concept to the completion of the final drawings. The design is based on a program that outlines the project’s general concept, most notably its identified uses and amenities, and initial allocations of floor area or acreage for each. It is increasingly common for planners or architects to participate in the programming phase, particularly in urban, mixed-use locations where this calculation can be very complex.

Initially, the architect prepares schematic drawings that include general floor and site plans and that propose basic materials and physical systems. A construction cost estimator or contractor should review the design and assess its economic implications at least at the conclusion of each design phase. These schematic drawings are an important component in presentations to lenders and should include a basic set of presentation images, such as rendered elevations or a physical or digital 3-D model.

Upon approval of schematic drawings, architects typically move into a “design-development” phase, where the original concept begins to be fleshed out into construction systems and a more precise division of functional spaces. Most major design decisions are made in the schematic and design-development drawing stages, and as each phase proceeds, changes to the design become more difficult and expensive. Even under the inevitable time constraints, it is nearly always better to address design concerns as they arise than to table these issues assuming they can be fixed later. The design team should include not only the contractor or construction manager but also marketing, leasing, and property management representatives. If those team members are not yet named, then the developer should ask potential contractors, brokers, and property managers to review and criticize the preliminary drawings. Beautiful, but unmarketable projects can lead to finger-pointing later.

After approval of the design-development package, the developer typically has the first real handle on the potential cost of the project. At this point, estimates are reviewed against the design drawings, and major budget busts should be resolved before going forward. Upon approval of the design and cost, the architect produces specification drawings, also called working drawings. Specifications include detailed drawings of the materials to be incorporated with the mechanical, electrical, plumbing, and heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning (HVAC) systems. Generally, drawings pass through several iterations before the final plans and specifications are finished. The developer should review these interim drawings, referred to as 25 percent, 50 percent, 75 percent, or 95 percent complete. After addressing all the developer’s concerns, the architect completes final drawings and specifications.

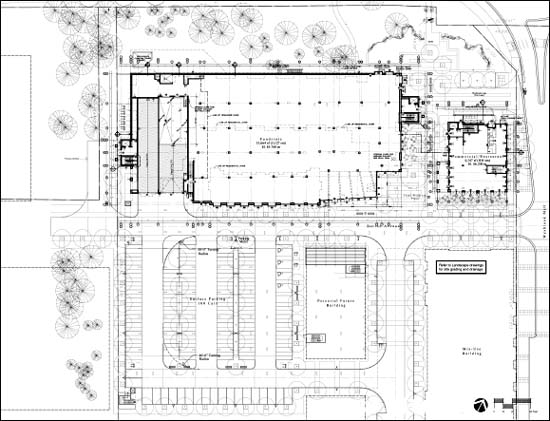

Site plans are the result of a team effort. Consultants should be involved early in the development process to ensure that they have a say in important decisions. Site plan for Granite Terrace, vancouver, Canada.

Because most developers are interested in the project’s image and feel, they often spend their time reviewing drawings, at the expense of specifications. Doing so is a mistake. The quality, durability, and safety of a structure are as dependent on “the spec” as on the drawings. The spec is typically organized around the Construction Standards Institute’s Master-Format, which groups construction materials into categories consistent across all types of projects, and a master specification defines not only materials but also precisely how and by whom each material should be installed. It is therefore an incredibly important document for the long-term operation of the building because it governs the warranty of nearly every material in the building. In reviewing partially completed designs, both drawings and specifications, the developer should pay particular attention to the implications for potential users by visualizing how commercial tenants or residents will react to the design, asking brokers, tenants, and other developers to identify the needs of the target groups and soliciting real estate professionals’ comments on the design drawings as they progress.

The next phase of the architect’s duties involves compiling the construction documents, including the package used to solicit bids from contractors. This package includes the rules for bidding, standard forms detailing the components of the bid, conditions for securing surety bonds, detailed specifications identifying all components of the bid, and detailed working drawings. The developer also relies on the architect’s experience to analyze the bids and to help select the best contractor for the job. Although the architect is best suited to understand the components of bids on a design, the developer is the one who will have to live with those bids, and with missing or misunderstood scope or cost during the development phase. For this reason, developers must thoroughly understand the bids, and they may wish to introduce special format requirements so that bids dovetail with the development and operating budgets they will be administering on the project.

Once construction begins, the architect is responsible for monitoring—but not supervising—the work site. The architect is expected to inspect the site periodically to determine whether contract documents are being adequately followed. Constant monitoring is beyond the scope of the architect’s responsibility, requires additional compensation, and is more effectively achieved with a fee-compensated construction manager.

The developer also relies on the project architect—or project engineer, in the case of infrastructure development—to confirm that predetermined phases during construction have been satisfactorily completed. The approval involves a certificate of completion necessary for disbursement of the contractor’s fee. The AIA provides another standard certificate that addresses the architect’s liability resulting from confirmation, noting that the architect’s inspections are infrequent, that defects could be covered between visits, and that the architect can never be entirely sure that construction has been completed according to the plan.

The relationship between architect and developer commonly follows one of two models. The design-award-build contract is most traditional in the United States and breaks the project into two distinct phases, with the architect completing the design phase before the developer submits the project for contractors’ bids. The alternative, the fast-track approach, involves the contractor during the early stages of design because the contractor’s input at this stage could suggest ways to save on costs, making the project more economical and efficient to construct.

The fast-track method is primarily a cost-saving device, as it uses time efficiently to reduce the holding costs incurred during design. The developer is able to demolish existing structures, begin excavation and site preparation, and complete the foundation before the architect completes the final drawings. One risk involved with the fast-track approach, however, is that the project is under construction before costs have been determined, and before necessary approvals are finalized.

Several methods are available for compensating architects for their services, including T&M agreements and fixed-price contracts. The latter specify the amount that the architect will receive for completing the basic services outlined in the performance contract; any duties not listed in the contract are considered supplementary and require additional compensation. Another method calculates architectural fees as a fixed percentage (usually 3 to 6 percent) of a project’s hard costs. Architects contend that this method fairly accounts for a project’s complexity. The disadvantage of this method is that it provides no incentive to the architect to economize. It is often necessary to engage the architect and other professionals on the basis of either T&M or a short-term retainer during project conceptualization, because the project scope remains unclear, and then shift to a fixed-price arrangement when the project is more defined and subject to better quantification. Hybrid models of compensation are also popular, where a particular milestone will be priced as a “not-to-exceed,” with hourly billing against the maximum, and no cost authorized beyond that number. In this way, the architect offers the client protection against overruns but is paid within an established range for work performed.

Regardless of the mode of calculating compensation, the architect is always entitled to additional reimbursable expenses—travel, printing, photocopying, and other out-of-pocket expenses. Beginning developers should be aware that, on a project with even a fairly simple path through public approvals, printing costs for the many dozens of required drawing sets can be well into five figures.

Landscape architects do much more than plant trees and flowers. Landscape architects work with existing conditions—topography, soil composition, hydrology, and vegetation on a site—to create a functional setting and a sense of place for the project. They are responsible for working with the architect to produce an external environment that enhances the development, for devising a planting and hardscape plan, and for incorporating components into the project, like plants, trees, furnishings (benches, for instance), walkways, artwork, and signs. Landscape architects can also save energy costs by selecting plants that provide shade and with grading and planting approaches that solve drainage problems.

It is becoming increasingly common for landscape architects to take a leading role in entitling projects. Communities commonly demand open space of new projects, and at any rate expect to have a say on landscaping of public roads and views. In land development projects, in fact, landscape architects may take the lead, because their drawings are often the most instructive to the community and, with emphasis on the green and natural, sometimes the most appealing vision of the project.

Landscape architects first develop preliminary plans and then manage the completion of those plans. They obtain bids, complete working drawings and final specifications, prepare a schedule, and inspect the site to verify that the contractor implements the plan correctly. Expertise in other kinds of construction does not necessarily translate into landscape construction and installation. Many very expensive installation problems in landscapes can be virtually invisible to the untrained eye—inadequate soils testing or preparation, or poor subsurface drainage—so it is advisable to have someone with specific expertise inspect the project at least upon completion, if not periodically through construction.

Hiring the landscape architect can be the architect’s responsibility, but developers should inspect the chosen landscape architect’s work to determine that they are comfortable with the design philosophy. The American Society of Landscape Architects maintains rosters and certifies its members. Landscape architects typically work through conceptual planning on a T&M basis, then bid a lump sum to complete working drawings and specifications, and, generally, return to working on an hourly basis to supervise completion of the plans. A monthly or weekly retainer may also be used for construction administration.

With land development projects and larger building projects, land planners allocate the desired uses to maximize the site’s total potential and determine the most efficient layout for adjacent uses, densities, and infrastructure. Individual building projects usually rely on the judgment of the architect and market consultants. The land planner’s goal is to produce a plan with good internal circulation, well-placed uses and amenities, and adequate open space. Land planners should prepare several schemes that expand on the developer’s proposal and discuss the pros and cons of each with the developer. The developer coordinates the land planner’s activities with input from marketing, engineering, economic, and political consultants to ensure that the plan is marketable, efficient, and financially and politically feasible. On land development projects, the land planner is the principal professional consultant. Reputation and past projects are the best indicators of a land planner’s ability. A key characteristic to look for in a land planner is the ability to work well with the project engineer and architect. Because the activities of a land planner vary widely, many architects and landscape architects offer “planning” on their menu of services. Although the skill sets certainly overlap, and some architects are definitely capable of high-quality site planning, professional planners often bring more to the table than simply their skills. When evaluating a planner, developers should be aware of the office’s relationships with the entities granting approvals, as well as its relationships with infrastructure contractors and landscape construction firms.

Engineers play a vital role in the development of a building. Several types of engineers with specific expertise—structural, mechanical, electrical, civil—are required to ensure that the design can accommodate the required physical systems. They are sometimes engaged by the project architect and sometimes contract directly to the owner or developer. Regardless of the relationship, they must maintain a very close relationship with the architectural staff as the project design unfolds. For this reason, the client should seek the architect’s input when selecting all the project engineers. Larger architectural firms may have an in-house engineering staff, which can expedite coordination but limit competition; smaller firms prefer to hire individual engineers project by project.

Although the architect may make recommendations or offer a list of candidates, the developer should reserve the right to select engineers after inspecting their qualifications; reviewing previously completed projects of the same scope and property type, including interviewing the project’s proponent; and checking their working references with various general contractors and local building inspectors. Contractors may have strong opinions about engineers that they have worked with in the past. Although these opinions should be considered, the developer should also understand that projects often place engineers and contractors on opposite sides of the process, and contractors can resent the oversight of an engineer.

Engineers must be licensed by each state in which they operate, and plans cannot receive approvals unless signed by a licensed professional engineer. Developers should clarify which submittals require stamps from which kinds of engineers.

The architect may hire certain engineers as subcontractors and then must be responsible for subcontract deliverables, schedule, and budget. Engineers are generally required on all substantial construction projects, including new developments, renovations, or additions to existing structures. The engineer’s fee schedule is usually included in the architect’s budget and generally ranges from 4 to 7 percent of the overall soft cost. When engineers subcontract to architects, evidence of payments to subs should be required in the architectural contract, because nonpayment or default by the architect can sometimes result in a mechanic’s lien5 on the property.

During the initial design phase, the architect works with the engineers to develop and modify working drawings to accommodate the project’s structural, HVAC, electrical, and plumbing systems. Each engineer then provides a detailed set of drawings showing the physical design of the systems for which the engineer is responsible. The architect is responsible for coordination of each successive drawing set and for instructing the engineers to resolve any conflicts.

Structural engineers assist the architect in designing the building’s structural integrity. They work with soils engineers to determine the most appropriate foundation system and to produce a set of drawings for the general contractor explaining that system in detail, especially the structural members’ sizing and connections. Structural engineers can range from sole practitioners who produce framing plans for single-family homes to large professional practices that can engineer steel-framed high rises. Developers of specialty buildings for medical offices, labs, and the like should be aware that these building types require specialized expertise beyond the generic professional engineer credential.

Mechanical engineers design the building’s HVAC systems, including mechanical plant locations, airflow requirements for climate control and public health, and any special heating or cooling requirements, such as computer rooms in office buildings or isolation wards in hospitals. Many firms offer a combined MEP (mechanical, electrical, plumbing) practice, allowing them to take responsibility for the building’s plumbing design, but developers should never feel obligated to lump all engineering specialties together in one firm if specific expertise can be found elsewhere.

Terrazzo is a ten-story residential tower located in the Gulch, a LEED-ND neighborhood in Nashville, Tennessee. The tower is certified LEED Silver.

BILL LAFEVOR, COURTESY OF CROSLAND

Electrical engineers design the electrical power and distribution systems, including lighting, circuitry, and backup power supplies and specifications for inbound site electrical utilities. Civil engineers design the on-site utility systems, sewers, streets, parking lots, and site grading. Wise project managers clearly delineate where each engineer’s jurisdiction terminates: for example, “site utilities” may extend to within three feet (0.9 m) of the building envelope, while “building electrical” may be within this boundary.

Effective project coordination relies on upfront communication, and engineers should be included early in the design process. Experienced developers generally facilitate a series of meetings with all architectural and engineering project personnel to define scope and communication channels and to discuss each discipline’s goals and objectives in depth. For example, if the goal is to construct a high-efficiency building with systems that result in lower operating costs—digital thermostats, automated or remotely monitored off-site HVAC system controls, automatic water closets—these project aims need to be spelled out early in the process. It is increasingly common for developments to aim for performance certification, such as LEED (Leadership in Energy and Environmental Design), EarthCraft, or at a minimum EnergyStar, and such goals magnify the importance of early engineering and cost-estimating coordination. Costs of LEED certification, for example, vary widely by product type and by the strategic choices made to get to certification. Increasingly, developers report that the “green premium” for more sustainable construction is falling rapidly, with faster payback as utility costs rise. Developers should be aware of cost tradeoffs between higher development costs and lower ongoing operating expenses and furnish engineers with the criteria they will need to make decisions on their behalf.

Ronald Stenlund, president of Central Consulting Engineers, advises developers and their engineers to insist on two-year warranties on all installed mechanical systems.6 It is vital that each component, particularly for a building’s heating and cooling systems, go through a full season of startup and shutdown to be evaluated. Unfortunately, a one-year guarantee is the industry standard, and this period generally begins on the shipping date rather than the installation date. Further, maintenance people must be properly trained in the nuances of each system and gain familiarity with their operations.

One concern of all developers is having their soft costs come in over budget. According to Stenlund, “Failure to achieve effective communication among the developer, architect, and engineering staff early in the process is the single most common cause for project delays, redesigns, and cost overruns. Coordinating the team early, defining expectations, and developing a congruent project vision are the three keys to minimizing this risk factor.”

Experienced developers recommend completing at least a few basic soils tests on a site before purchasing the property. Soils engineers can conduct an array of tests to determine a site’s soil stability, the level of its water table, the presence and concentrations of common toxic materials, and any other conditions that will affect construction. Geotechnical engineering is not an exact science, but hiring skilled, registered professionals reduces uncertainty and can at the very least indicate whether further testing should be conducted.

A soils engineer first removes a cross section of the soil by boring the surface of the site to a specified depth. That sample is then analyzed. Laboratory tests disclose the characteristics of the soil at various levels, the firmness of each of those levels, and, if requested, the presence of certain toxic materials. On smaller sites with no water or other potential problems, one boring test in the middle may be sufficient. On other sites, boring tests are usually completed in the middle and near the anticipated building corners and critical roadway or bridge locations. If the presence of toxic materials is suspected across the site, more borings may be necessary, but the project engineer should be consulted for a customized test approach. The soils engineer prepares a detailed report on the composition of the underlying soil, complete with an analysis of the characteristics of each layer. Soil composition is classified according to color, grain size, and firmness. The soils engineer also recommends the type of foundation system most appropriate for the site, based on the laboratory findings and tests to determine the soil’s strength.

A bearing test determines the soil’s ability to support the planned structure at the anticipated depth of the foundation. The soils engineer digs out a portion of the site to the designated level to complete the test. The soils engineer also determines the stability of the site’s slope. During excavation, for example, digging straight down may be difficult because the remaining soil might cave in. The engineer is expected to use the results of the test to calculate the excavation angle that will leave the remaining soil intact.

Soils engineers participate with the architect and the structural engineer to design the most effective type of foundation system to support the proposed structure. They generally work on a lump-sum basis. A soils analysis can cost from $1,000 to $100,000, depending on the site’s size and the number of test borings and types of tests necessary.

Though increasing environmental regulation has resulted in a substantial increase in specialty environmental consulting for real estate, there are two basic types of environmental consultants: one type, engaged during feasibility and approvals, analyzes the project’s economic, social, and cultural effects on the surrounding built environment; the second type, engaged in the design phase, determines, in conjunction with soils engineers, mitigation for impacts associated with the development. Impacts can range from intrusion on streams or wetlands to increases in traffic, noise, and emissions. Planning and budgeting for environmental consultants can only follow a solid understanding of the regulatory process. Land use attorneys and planners are good sources of information, and they should be consulted early. Some aspects of on-site evaluation require long lead times, and some can only be accomplished during certain times of year. Emergent or seasonal wetlands, for example, might only be identifiable when wetland-associated plants are visible in the spring. The developer must also understand at what point in the approvals process formal environmental reviews are required.

Environmental reviews are often necessary for development projects of significant size and scope, and they are generally required and administered by state environmental quality agencies. Reviews usually focus on impacts to the immediate surroundings caused by the proposed development, such as increased traffic, reduced air quality, sunshine and shading, and infrastructure requirements.

The environmental approval process varies in rigor based on state and local regulations and attitudes. These reviews are often sensitive political actions and demand a balancing diplomacy and insistence from the developer. Although no developer wants to be perceived as an environmental threat, it is also important to insist that statutory timelines and requirements are followed, as many developers have found the environmental review process to be abused by project opponents as a way to delay legitimate and low-impact projects.

The financial outlay, time, patience, and perseverance required to successfully navigate an environmental review and secure final building permits must not be underestimated. The process is governed by the appropriate level of government that first determines whether or not a developer is obligated to complete a formal environmental analysis, and which tier of study is indicated by the project. This process is triggered if a project exceeds various size or scale thresholds or affects environmentally sensitive areas, such as wetlands or an endangered species’ habitat. Empowered by federal legislation, including the National Environmental Policy Act of 1969, each state and locality has created its own environmental laws to which developers must adhere, and these laws vary widely.

Biltmore Park Town Square in Asheville, North Carolina, integrates retail and entertainment uses, offices, a hotel, and a variety of residential types on a 57-acre (23 ha) site. The master plan is LEED-ND certified.

PATRICK SCHNEIDER PHOTOGRAPHY