Comcast Center is a 58-story office and retail development in the heart of Philadelphia’s downtown.

Office development is a critical component in the economic vitality of urban and suburban areas, with location and market conditions influencing the type of structure. Office users can vary widely in size, occupying spaces from 500 square feet (46.5 m2) to several million square feet.

This chapter focuses on office buildings most frequently built or retrofitted by beginning developers—costing under or around $10 million and ranging from 5,000 to 100,000 square feet (465-9,300 m2).

The increasing adoption of technology, sustainable practices, and the aftermath of the Great Recession along with its lasting effects create a new reality for all developers, especially those new in the field.

Office developments are categorized by class, building type, use and ownership, and location.

CLASS. The most basic feature of office space is its quality or class. The relative quality of a building is determined by a number of considerations, including age, location, finish materials, amenities, and tenant profile (see figure 5-1). Office space is generally divided into three major classes:

1. Class A—New highly efficient properties in prime locations with first-rate amenities and services, as well as older significantly renovated or upgraded buildings with prestigious or landmark status. They achieve the highest possible rents and sales prices in the market. Certain office developers acknowledge an A+ class for LEED-certified properties achieving 10 to 15 percent energy efficiency versus comparable buildings.1

2. Class B—Older, somewhat deteriorated buildings in good locations with finishes, amenities, and services that are lower than Class A. Newer properties might also be designated as Class B if they offer lesser services and amenities. They achieve lower rents and sales prices compared with Class A properties.

3. Class C—Facilities with inferior mechanical and building systems, below-average maintenance, and very limited services compared with Class B. Rents and sales prices are the lowest in the market and are often in less attractive locations than Class A or B buildings.

BUILDING TYPE. Four major office building types are widely used for categorizing purposes:

1. Typical Office—Single structure located in downtowns or suburbs with office use being the main revenue stream; possibly a minor retail component;

2. Mixed-Use Development (MXD)—One or more structures combining at least two significant revenue streams (for example, retail, office, residential); suburban MXDs cover more than 100 acres (40 ha) with buildings of various heights;

3. Garden Office—Low-rise structures clustered together in office parks with extensive landscaped areas; and

4. Flex Space—One- or two-story buildings usually located in business parks that facilitate an office component combined with space for light industrial or warehouse use.

BUILDING HEIGHT. Buildings are categorized by height as follows:

• High-Rise—Typically higher than 12 stories;

• Mid-Rise—Four or five to 11 or 12 stories; and

• Low-Rise—One to three or four stories.

The Council of Tall Buildings and Urban Habitat suggests that better indicators of building height designation are (1) height relative to context (comparison with other structures in the area and local zoning codes), (2) proportion (slenderness of the building against low urban backgrounds), and (3) tall building technologies (for example, vertical transport technologies).

USE AND OWNERSHIP. Office buildings can also be classified by their users and owners. Buildings can be single- or multiple-occupant structures. A single-occupant building may be leased from a landlord or owned by the tenant. In the latter case, it is referred to as an owner-occupied building. A building designed and constructed for a particular tenant that occupies most or all of the space is called a build-to-suit development. A single- or multiple-occupant building designed and developed without a commitment from a tenant is considered a speculative (spec) building.

Medical office space is often a unique product, designed specifically for doctors’ offices. It can be single-tenant or multiple-tenant space. It is often located in a campus setting near a hospital, or even on hospital grounds.

LOCATION. In most urban areas, at least four distinct types of office nodes can be found, distinguished by their location:

1. Central Business District (CBD)—High land costs in CBDs encourage more vertical development in the form of mid-rise and high-rise structures. Typical tenants in downtown offices include Fortune 500 companies, law firms, insurance companies, financial institutions, government, and other services that require high-quality prestigious space.2

2. Suburban Locations—Since the latter part of the 20th century, a decentralization trend has led to greater diversity in office locations outside the city center. Suburban nodes of large and small office buildings are often found in business districts, in clusters near freeway intersections, or in major suburban shopping centers. Rents are traditionally lower than the CBD and tenants include regional headquarters, high-tech and engineering firms, smaller companies, and service organizations that do not require a location in the CBD.

3. Neighborhood Offices—Small office buildings are frequently located away from the major nodes, where they serve the needs of local residents by providing space for service and professional businesses. Neighborhood offices can be integral parts of neighborhood shopping centers or freestanding buildings.

4. Business Parks—Business parks include several buildings accommodating a range of uses from light industrial to office. These developments vary from several acres to several hundred acres. Flex-space office buildings, with capabilities for laboratory space and limited warehouse space, are typically located in business parks.

In recent years, some developers and tenants have focused on dense urban transit-oriented locations rather than greenfield sites. Suburban areas are increasingly undesirable for certain companies and developers due to suburban sprawl, the resulting traffic, and the lack of public transportation. Substantial rent increases in suburban areas over the last 25 years have further increased the desirability of urban infill locations. However, companies interested in lower-cost space and labor, as well as build-to-suit facilities, will continue to find suburban locations attractive.3

The office market is a highly cyclical business that is subject to boom and bust periods. The playing field for office development comprises many elements, and unforeseen changes in basic forces can influence office markets in unexpected ways.

MARKET TRENDS. In the 1980s, significant increases in liquidity combined with investor and developer optimism on demand and rents led to significant overbuilding, causing substantial vacancies—around 20 percent—in the early 1990s. It took ten years of economic expansion with relatively little new office construction to decrease the national vacancy rate to around 10 percent—when 5 percent is considered the “normal” rate. Development started increasing when the 2001 recession (caused by the dot.com bubble and attacks of September 11, 2001) triggered employee layoffs and corporate cost cutting, leading to higher vacancies and lower rents. The short recession of 2001 was followed by the Great Recession, creating a financially frozen market (lack of debt and equity). Although the Great Recession ended in 2009 its effects remain into 2012, with vacancies hovering around 13 percent while development continues to face challenges. The lack of corporate reinvestment, anemic job growth, tight capital, and lack of credit market liquidity marginalize development. Regardless of project type, location, or leasing activity, construction loans remain difficult to obtain. In 2007–2008, the preleasing requirement for office buildings was 40 to 50 percent; by the summer of 2010, it increased to 75 percent, with an equity requirement of 20 to 30 percent and substantial guarantees.4

RECENT FINANCIAL TRENDS, CREDIT FREEZE, WORKOUTS. Several factors caused the credit freeze in commercial lending from 2008 through 2010:

• significant exposure of lenders to residential defaults/capital losses;

• a major shift of commercial bank asset portfolios to real estate (37 percent in 2007 compared with 25 percent before 2000);

• poor due diligence and underwriting standards (investors and capital providers overrelied on quality ratings by rating agencies, such as Moody’s, rather than in-depth due diligence, leading to significant suppression of cap rates from 2000 to 2006;

• a widespread lack of transparency in financial dealings and instruments; and

• a mismatch of duration between borrowing short and lending or investing long.

Two additional factors affected commercial property liquidity of suppliers, beyond bankers:

• perception of risk after the bust of the housing bubble and the possibility of a commercial bubble due to the continuing price increases; and

• international accounting standards (promoted by the Securities and Exchange Commission) requiring property owners/investors to identify the fair or true market values of their assets when computing their balance sheets.5

As a result of the Great Recession, a number of under-construction office projects required workouts. The approach used in each workout is different due to the parties involved, type of lender, problem, and reputation of the developer. Some insights are provided regarding some causes of project challenges during and after the Great Recession:

• Development participants were not conservative enough; they became increasingly greedy, in part due to market liquidity.

• Developers were significantly overleveraged, assuming they would refinance with improved terms or sell the asset for profit when the loan was due.

• Developers underestimated budget expenses, which were not finalized before construction.

• Developers’ capital structure was problematic with significant debt, minimal equity, and not enough preleasing.

• Permits were not secured and/or were delayed by local municipalities, adding to costs.6

FIGURE 5-1 | Characteristics Determining Office Classification

INFLUENCE OF TECHNOLOGY. Technology is the driving force behind increased efficiency and long-term cost savings. Technologies such as Building Information Modeling (BIM) can be applied in the design and construction process, as well as used in the building automation system (BAS). The BAS allows building managers and owners to monitor and create efficiencies in major building systems, such as heat exchangers, automatic dimmers, and OLEDs (organic light-emitting diodes), creating “smart” buildings with single rather than multiple network systems communicating through Internet protocol.

A developer’s budget, market conditions, and the type of tenant pursued will determine the most balanced approach regarding the applied technology innovations and the rent premium tenants will be willing to pay. Developers should also review the various incentives offered by local, state, and federal governments. An excellent source on renewable energy and energy-efficiency incentives is the Database of State Incentives for Renewable Energy (www.dsireusa.org/). DSIRE was established in 1995 by the U.S. Department of Energy

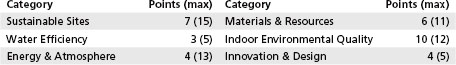

GREEN DEVELOPMENT. The two most popular green property designations are Energy Star,7 launched by a joint effort of the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the Department of Energy in 1992, and LEED,8 launched by the U.S. Green Building Council in 1998. LEED is designed around a point system, as shown in figure 5-2. The most recent LEED guidelines (Version 3.0) were released in 2009, with four relevant ratings for office buildings:

• LEED-NC (New Construction);

• LEED-CI (Commercial Interiors);

• LEED-CS (Core & Shell); and

• LEED-EBOM (Existing Buildings Operations & Maintenance).

Some developers consider Energy Star more meaningful than LEED because it emphasizes energy efficiency with a greater impact on the operating budget. LEED certification, however, can be accomplished with little or no financial premium if the building has modern systems and a curtain wall. Some driving forces behind LEED construction include a higher likelihood of obtaining bank financing with lower interest rates for construction and permanent loans; pension fund investment interest; and increasing preference among Fortune 500 and other companies with green mission statements.9

Developers and managers of both new and existing sustainable properties face certain financial challenges. From an operating budget standpoint, the upfront capital required for LEED certification might take more than three years to recapture, which can exceed the developer’s holding period. Further, the cost savings cannot be easily determined yet because of (1) the small number of LEED buildings with historical information, (2) a lack of documentation on the cost savings received separately by the tenants and the building, (3) minimal documentation on changes in employee satisfaction and health patterns, and (4) the disparity between who pays for most of the LEED certification and who reaps the benefits, with tenant participation in the cost still lagging.10 However, new and revised building codes are increasing the energy-efficiency requirements, thereby reducing the cost premiums to achieve LEED certification.

Research on the effect of sustainability on real estate is expanding. Eichholtz, Kok, and Quigley’s11 study of a group of green and nongreen comparable properties identifies a premium of 3 percent in rents and 16 percent in prices for the green properties. Fuerst and McAllister,12 as well as Miller, Spivey, and Florance,13 also found premiums among the green versus the nongreen group of properties. A study by Dermisi14 of the spatial distribution patterns of LEED ratings and certification levels across the United States suggests aggregations in certain areas with certification levels affecting the total assessed values of office properties.

SUBURBAN VERSUS URBAN. The dispersed and low-density nature of most suburban offices causes transportation challenges. Despite certain large companies (such as Apple and Cisco) continuing to locate in sprawling suburban areas, developers are also noticing that companies targeting a young, highly compensated and/or specialized workforce are more likely to be located downtown or close to a transit line. Beginning developers should consider opportunities in urban infill developments that are ripe for redevelopment, assuming they are financially feasible and the complex permitting and approval processes and codes are understood.

CORPORATE CAMPUSES. A countertrend to the move back to the city has been the move of major corporations into corporate campuses. During the 1990s, for example, Sears vacated its namesake tower in Chicago and relocated to a suburban campus. In Kansas City, Sprint has created a new 240-acre (97 ha) headquarters campus in the suburb of Overland Park. USAToday’s headquarters moved from a high-rise tower close to downtown Washington, D.C., to a campus in suburban Virginia.

Some technology companies are embracing green corporate campuses, such as Google’s headquarters in Mountain View, California. Google’s facilities are built with sustainable materials and are designed to maximize fresh air ventilation and daylight penetration. All rooftops are covered with solar panels, while biodiesel shuttle service is available to all employees from the Bay Area. Points for charitable donations are provided to those who use other green transportation means, such as biking or walking. The campus also has plug-in vehicles and multiple bikes for intercampus movement.15

The first task for developers is to conduct a market analysis, a critical assessment tool for any successful project, to determine whether a market exists for additional office space. It also provides direction for site selection and design by indicating the type of space and amenities that office users are looking for. The market analysis also provides critical input for the financial analysis, which will ultimately be used to demonstrate the feasibility of the project and to provide investors and lenders with the information they need to fund the project (see figure 5-3).

Market analysis requires a combination of data sources and usually the assistance of a market research firm, although the developer should be sufficiently familiar with the market to make an initial determination of whether the project is likely to be feasible. Brokerage firms can be a source of major tenant information, leasing activity, and overall market trends. These firms also know what the current trends in the market are and what segments of the market have the largest unmet demand.

The market analysis is a study of demand and supply, which ultimately determine vacancy rates, rents, cap rates, and property values. It should survey the economic base of the local metropolitan area, including existing employers and industries and their potential for growth. It should also identify whether the market contains headquarters, regional, or branch offices. The type of tenant to be targeted will affect the design with respect to office depths, parking, amenities, and level of finish.

Developers should keep in mind that companies seek new space for several primary reasons:

• to accommodate additional employees or a new subsidiary;

• to expand an existing business;

• to improve the quality of their office environment;

• to consolidate dispersed activities into a single space; and

• to improve their corporate image (thereby improving both sales and customer contacts and enhancing employees’ morale).

FIGURE 5-2 | Office-Related LEED Ratings and Certification Levels for Office Buildings

DEMAND. The first step in any market study is to define the area of competition in the submarkets and in the region. For regional employment, a step-down approach can be used to allocate employment growth from the region to the local market. Office buildings compete most closely with other buildings in the immediate vicinity. Rents, amenities, parking, and services can vary considerably among submarkets, though regional conditions affect all submarkets. It is therefore important to understand how a particular development will address its competitive environment. The analysis of the metropolitan economic base involves studying existing employers and industries in the market and their growth potential, with particular focus on the sectors of the economy that generate demand for office space.

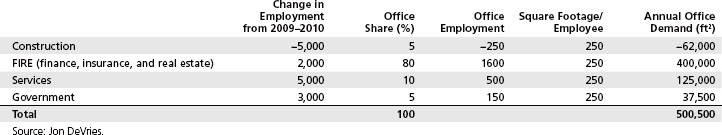

Projected employment growth is the key driver of office space demand. It includes new and expanding firms in the area, broken down by industry, ultimately yielding office-based employment growth projections for the local economy. Local employment projections are available from commercial brokerage companies as well as local governments and chambers of commerce. When an area’s projected office employment is available, the following equation can be used to estimate the total square footage demanded:

Projected office space demand =

Number of projected office employees

× Gross space per employee

If area employment projections are not available, the following formula can be applied to determine the annual demand in square feet (see figure 5-4):

Office employment demand of industryi =

Change in employment of industryi in the last two years

× Office share of industry,

Annual office demand in square feet for industryi =

Office employment demand of industryi

× Area’s gross space per employee

where i represents a specific industry

that drives office demand.

FIGURE 5-3 | Market Analysis Data and Sources

The annual office demand in past years is then used to project future trends of more than ten years.

Two good resources for the amount of space required per employee are Building Owners and Managers Association (BOMA) International’s Experience Exchange Report and the Institute of Real Estate Management’s (IREM’s) Income/Expense Analysis: Office Buildings Report.

The demand for space is also affected by market rents and tenants overleasing when space is readily available and rents are relatively low. Over time, office space per employee has tended to decline.

Users’ space requirements inevitably affect the design and type of facility, including average floor area, number of entrances, and the location of hallways and elevator cores. The bay depth—the distance between the glass line and the building core—is particularly important. Large users frequently desire large bay depths, but small users require smaller bay depths to increase the proportion of window offices. Space requirements are influenced by a potential tenant’s mix; 200 to 250 square feet (18.5–23 m2) per employee is now considered the norm due to the elimination of file cabinets and improved space efficiency, but space requirements per employee can vary greatly. Office cubicles can range from 6 by 6 feet (1.8 by 1.8 m) to 8 by 8 feet (2.4 by 2.4 m), while the physical office room space in most offices is 10 by 12 feet (3 by 3.6 m) or 10 by 15 feet (3 by 4.5 m). Although spaces are tight, they can become tighter if workers lack individual privacy, with more conference and phone rooms.16

Other critical components of the demand analysis include the determination of the annual net absorption, the obsolete space, and the net rentable square footage demanded per year. Net absorption represents the net change in the amount of occupied space in the market. Obsolete space could be replaced by new Class A space. All Class C space older than 50 years will likely be replaced within the next 20 years at a rate of 5 percent per year.

SUPPLY. After establishing market demand, the analysis should focus on the competitive supply within the market. The supply information gathered provides the basis for estimating rents, concessions, design features, desired amenities, and finishes. The key elements of the supply analysis are an inventory of existing competitive buildings within the market area and projects under construction and in planning stages. An inventory of competitive buildings should include the following information:

• location;

• gross and net building area;

• scheduled rent per square foot per month;

• lease terms;

• tenant finish allowances;

• building services;

• amount of parking provided and parking charges (if applicable);

• building and surrounding area amenities (restaurants, conference facilities, health clubs, and so forth); and

• list of tenants and contact people.

This information provides the basis for estimating rents, concessions, design features, and desired amenities. The market area for supply should take into account regional and metropolitan supply. The submarket definition—areas that include the primary competitors for the subject project—is especially important. All competitive buildings in this area should be carefully documented.

The analyst should determine total existing supply plus the future supply of office space. By subtracting the expected supply from the expected demand for office space, the deficit or surplus of office space for a particular period can be determined. This knowledge allows the developer to estimate the market conditions that will prevail when the proposed building comes online. Vacancy levels are an important part of the supply calculation and vacancy trends can indicate changes in demand. If demand is increasing faster than supply, vacancy rates should be falling, creating a more favorable market for the developer. Alternatively, if supply is increasing faster than demand, vacancy rates should be increasing. The vacancy rate resulting from turnover, sometimes referred to as the natural or stabilized vacancy, is inevitable.

FIGURE 5-4 | Use of the Annual Office Space Demand Formula by Industry

The absorption time, in months, of all the vacant space can be calculated as

where t represents the quarter or year the estimates takes place and t-1 the previous period.17

For an application of the AT equation, assume that the area of interest has 600,000 square feet (55,700 m2) under construction, with a vacancy of 1.5 million square feet (139,000 m2) and a net absorption of 1 million square feet (93,000 m2), and will require a 25-month absorption period. The AT equation assumes that the rate of new demand growth continues as indicated by the net absorption rate and that there is no new construction in the market other than what has already been started. No firm guidelines exist for determining what constitutes a soft market, although a market with fewer than 12 months of inventory is considered a strong market, 12 to 24 months a normal market, and more than 24 months (18 months in slower-growing areas) a soft market.

A common mistake is to assume that a proposed project will capture an unrealistically large share of the entire market. Developers should have sufficient cash available to cover situations in which leasing takes longer than expected, which can be influenced by such factors as timing of the project delivery, amenities, rent levels, and especially market conditions.

SUBLEASED SPACE. It is important to recognize subleased space in assessing supply because, although technically leased, it is often available, formally or informally, and is thus part of the market competition.

In the late 1990s, some firms engaged in defensive leasing to ensure their future ability to expand in prime locations. But when their growth plans did not materialize, they were forced to sublet the space.18 In markets where vacancy rates are low, if unanticipated subleased space and new product come online simultaneously vacancy rates can soar. Recent economic downturns have led to the availability of large blocks of subleased space.

SHADOW SPACE. Vicky Noonan of Tishman Speyer defines shadow space as “a leased space for which a tenant pays rent but it is vacant or not fully occupied and it is not yet available for sublease.”19 It is a potential threat to a building’s rental stability and market recovery during a down cycle because an increase indicates tenant contraction, which can eventually increase vacancy if the trend continues. The presence of shadow space is inefficient for a landlord because it cannot be considered stable income and the space could be offered on the market with a better return. Unfortunately, none of the published data sources track shadow space, and developers can only assess it by talking to area property managers. A rule of thumb in estimating the extent of the shadow space in suburban properties is to look at the building’s parking lot. If a building occupancy rate is more than 90 percent, but there are consistently plenty of available parking spots, it is an indication of possible shadow space.

EFFECTIVE RENTAL RATES. An important distinction in office market analysis is the difference between quoted (face) rents and effective rents. Property owners sometimes use incentives to maintain the appearance of certain rent levels while effectively reducing rent for certain times or tenants. Typically, lenders determine a specific rent and preleasing threshold as a condition of funding or for releasing of the developers’ personal guarantee on the construction loan. To meet these conditions in a soft market, developers may offer tenants concessions in the form of free rent for a specified period, an extra allowance for tenant improvements (TIs), or moving expenses, as long as the rent meets the lender’s requirements. The extent of the TIs is always market driven, with tenants pressuring landlords for more during periods of increased construction costs. Today, TIs are on average $5 to $6 per square foot ($54-$65/m2) per year of lease-term for Class A (for a ten-year deal, it is $50 to $60 per square foot [$540-$650/m2]) properties, while TIs for downtown new Class A buildings are $70 per square foot ($753/m2) and for Class B properties $30 to $50 per square foot ($323-$538/m2) for a seven-year lease. TIs for suburban office buildings are about $20 per square foot ($215/m2).20

Rental concessions are harder for market analysts to identify than asking rents because brokers tend to understate concessions due to the negative influence on their commission. Factors influencing the number and amount of concessions include tenant size, lease term, and tenant rating. Concessions remain common practice across markets, especially during economic down cycles, and lenders generally use effective rents in their analyses before funding a loan. In strong markets, building owners do not offer free rent, except perhaps during an initial period when tenant improvements are being completed.

The Studley Effective Rent Index provides in-depth analysis of major real estate markets for Class A office properties, including effective rental rates, concessions, and a breakdown of rent components (net rent, operating expenses, real estate taxes, and electricity).

Scheduled rental rate increases change the effective rent. For example, a lease with flat rent for ten years has a lower effective rate than a lease with annual 2 percent increases. A lease with annual 2 percent increases is likely to have a lower effective rate than a lease with annual increases tied to the consumer price index, because the CPI historically has increased more than 2 percent per year.

Calculation of Effective Office Rent

Suppose a developer has an office space of 1,000 square feet (93 m2) with a nominal rent of $24 per square foot ($258/m2) for five years. Concessions include six months of free rent and $3 per square foot ($32/m2) in extra tenant improvements. The developer’s discount rate is 12 percent. To find the effective rent, the developer must convert the lease and the free rent to present value, which can be computed per square foot.

GENERAL ADVICE ON OFFICE MARKET RESEARCH. When conducting office market research, developers should keep the following trends in mind:

• Tenants will continue to downsize and consolidate their office space in an effort to minimize their costs and improve their efficiency while reducing redundancy.

• Buildings with flexible floor plates are becoming increasingly attractive to tenants.

• Green, energy-saving, and energy-producing buildings are increasingly important for perspective tenants.

Allan Kotin of Kotin & Associates and the University of Southern California offers additional comments:

• The larger the tenant, the more difficult it is to determine what the tenant is actually paying in rent after taking into account rent concessions, such as free rent, expense caps, free parking, and extra tenant improvements.

• A problem with assessing the effect of larger tenants is their susceptibility to consolidations or changes in business plans from swings in the economy. Such actions can result in their putting large amounts of space on the sublease market.

• Major markets are stratified by scale as well as by quality, rent, and location. A 10 percent vacancy rate may be very misleading if the largest space available is only 20,000 square feet (1,860 m2). The market for 50,000-square-foot (4,650 m2) tenants is very different from that for 100,000-square-foot (9,300 m2) tenants.

• For major buildings, control of a single large tenant is far more important than generic measures of space.

• Despite the sophistication of market analysis, the fact remains that many small and medium firms decide where to rent space on such distinctly unscientific grounds as “where the boss lives.”21

Site selection is a crucial step in the project feasibility analysis because it directly affects the rent and occupancy levels. Developers should compare location, access, physical attributes, zoning, development potential, and rents and occupancy of comparable buildings and sites to identify potential opportunities and obstacles.

In general, office use can support the highest rents of any land use type and thus is often located on the highest-priced land. This factor should not deter developers because a high price is usually indicative of site desirability. Similarly, developers choosing sites based on a lower price can find themselves unable to compete in the market, even at lower rents.

The site should be able to accommodate an efficient building design. Office buildings are less flexible in size and shape than are most other development types. Floor plates (area per floor) are a key factor in a building’s suitability for a tenant. Those deviating significantly from 25,000 square feet (2,322 m2) require more than one building core due to the travel distance required of individuals. A second core substantially increases building costs because it requires additional stairwells, restrooms, and elevators).22 Developers should make sure that a larger structure will be in demand in the area. Small office users prefer buildings with floor sizes ranging from 16,000 to 20,000 square feet (1,500–1,860 m2), although smaller floor plates are not uncommon. The most efficient buildings are 100 feet wide and 200 feet long (30 by 60 m). Such a shape allows a core of about 20 by 100 feet (6 by 30 m) and a typical depth of around 40 feet (12 m) between the core and the exterior wall. Such plain rectangular boxes might be the most cost-effective, but prospective tenants may respond negatively depending on their type of business. For example, major law firms seek buildings that make a statement with their exterior facade and interior amenities, while call centers do not.

When land values are high, the cost of parking structures is often warranted, and parking structures are less flexible than buildings in their layout. Structured parking modules with efficient layouts should be designed in bays that are 60 to 65 feet (18–20 m) wide, with a minimum of two bays; therefore, a parking structure needs to be at least 180 feet (16.5 m) long to efficiently accommodate internal ramps.23

Topography can play an important role in site selection. Hilly sites may require extensive grading, which will increase construction costs, but they may also provide excellent opportunities for tuck-under parking that requires less excavation than a flat site.

Access is a primary consideration in site selection. Sites should have convenient access to the regional transportation system. Public transit options are important in urban locations. Developers should check the site’s highway and transit access with transportation authorities before proceeding, as well as the need for a traffic study.

Jim Goodell of Goodell Associates recommends that office buildings be located in areas with a sense of place. “A synergy exists between office buildings and activities such as restaurants, shopping, entertainment, hotels, and residential uses. A mixed-use environment generates benefits that translate into higher rents and better leasing.”24

Historically, office developers were concerned only with local zoning and building codes. Floor/area ratios (FARs), height limitations, building setbacks, and parking requirements were the primary determinants of how much space could be built on a particular site.

Today, communities often have wide discretion in reviewing projects not only for compliance with zoning but also for environmental and community impacts that are difficult to quantify. In some cases, specific impacts, such as increased traffic at a particular intersection, can be addressed by constructing offsite improvements, such as traffic signals or turn lanes. Others, such as increased regional congestion or lack of affordable housing, may be mitigated through the payment of impact fees.

Office developments generally have a positive fiscal effect by generating more in tax revenues than they require in public services. Shrinking local tax revenues from other sources have led many cities to look toward office development as a way to fund public projects and affordable housing, which has backfired in some cases, particularly when the economy weakens. For a time, San Francisco experienced an exodus of businesses from the city’s core when it instituted a combination of very high impact fees, exactions, and housing linkage programs.

Certain cities are in such distinctive and attractive locations that they can exact above-average concessions from developers, but even these cities have suffered a slowdown of new business development when the cost of their exactions made development unprofitable. Developers pass on the regulatory costs to future tenants in the form of rent or operating expenses and depending on the market conditions, tenants might seek space elsewhere.

Government bodies continuously revise local building codes covering building safety and public health, spurred in some cases by litigation or the threat of litigation. Many government agencies have also enacted stringent energy codes. This trend toward stricter building codes will likely continue.

ZONING AND LAND USE CONTROLS. In addition to the typical zoning restrictions on building setbacks, height, and site coverage, the regulations specifically affecting office development include FARs, building massing, solar shadows, and parking requirements. FAR is obtained by dividing the gross floor area of a building by the total site area. Some cities—Los Angeles, for example—have dramatically reduced allowable FARs, giving cities unusual leverage in negotiating with developers for facilities or services the city wants.

Some cities, including New York and Chicago, award FAR bonuses to developers that embrace sustainable development practices or provide public amenities in high-density commercial districts. For example, the FAR of One South Dearborn in Chicago, completed in 2005, increased from 16 to 21.27. The combination of a park in front of the building, the ground-floor retail, and the setback, which reveals the north elevation of the Inland Steel Building—a Chicago landmark—allowed for the additional credit.25

Most zoning ordinances include provisions that carefully define allowable building envelopes and shapes to stop buildings from casting permanent shadows, to prevent streets from becoming canyons, and to prevent the glass on buildings from reflecting excessive heat onto other structures. In addition, some government agencies regulate the types of materials, styles of architecture, locations of entries, and various other design aspects of office projects. Developers must recognize and work within these restrictions to determine the maximum envelope that their buildings can occupy.

One special regulatory device that has been used with urban office development is transferable development rights (TDRs). Although not widely adopted, TDRs allow for the sale of development rights on a property from one owner to another. If one owner wants to retain a two-story building on a site zoned for ten stories, that owner may sell the right to build the additional square footage to another landowner. Once sold, however, the original owner cannot build any more square footage than that for which zoning rights were retained. A number of obstacles exist in establishing a TDR (for example, allocating higher-density development, calibrating values for development rights, and creating a program that is simple to understand and administer but also fair). TDRs work well with historic landmark buildings because they might not take the fullest advantage of a site’s development potential. In addition, designation of older buildings as historic landmarks can complicate and even prevent major changes to their structure and exterior facade.

Parking requirements vary by location and building type, but they typically stipulate a minimum of three to four spaces per 1,000 square feet (95 m2) of rentable floor area. Developers often find that they must provide more spaces than required in order to secure financing. Communities wishing to encourage use of mass transit may however restrict the amount of parking. Some cities have also proposed mandatory off-site parking for some portion of the parking requirement for buildings in congested downtown areas. One concept that can satisfy local government’s desire to limit parking while providing the ability to meet tenants’ future needs is deferred parking. Deferred parking is shown on the approved development plan but need not be built until demand for parking is proved.

Local communities have also become increasingly concerned about the aesthetics of office developments. Although developers and their architects do not always appreciate the opinions of regulators, local planning staffs and officials are not shy about expressing their preferences about building massing and shape, exterior materials, and finishes.

JAS Worldwide International Headquarters is a renovation of three vacant, obsolete buildings in Atlanta. The amount of green space was increased through removal of unnecessary parking.

MIDCITY REAL ESTATE PARTNERS

TRANSPORTATION. A development’s traffic impact is a politically sensitive issue with congestion increasing beyond the central cities into the suburbs.

An increasing number of office developments are now required to provide a traffic impact study during the approval process due to the increased traffic loads in peak hours. Traffic mitigation measures can range from widening the streets in front of a building to adding a traffic signal or widening streets and intersections surrounding a site. Satisfying off-site infrastructure requirements can be extremely costly and time-consuming, not least because of the need to work with public agencies and other property owners.

An office developer may be required to undertake any of the following actions:

• restripe existing streets;

• add deceleration and acceleration lanes to a project; construct a median to control access;

• install signals at entrances to a project or at intersections affected by the project;

• widen streets in front of a project or between a project and major highways or freeways;

• build a new street between a project and a major highway; or

• contribute to construction of highway or freeway interchanges.

Instead of requiring certain improvements through exactions, some areas have created impact fee programs (assessed per peak trip generated or a fee per square foot) to cover traffic improvements. The number of expected peak trips generated by the project becomes a critical factor in the cost of the project because fees can be as high as several thousand dollars per peak trip generated. Peak traffic trips can be reduced by (1) adding a minor retail component to a project (a major retail component can possibly increase the traffic impact), (2) providing residential facilities on or adjacent to the site, and (3) providing links with public transportation systems.

Transportation demand management (TDM) programs (or transportation system management) have become a popular mechanism for reducing traffic. A number of cities require large projects to implement ride-sharing programs, such as car- or vanpools; to include reduced-price passes for public transit; and to provide preferential parking spaces for individuals who carpool. The developer is often responsible for ensuring the implementation of TDM programs because they are often a condition of approval. Commuting by bicycle or foot is another strategy some cities encourage while properties receive LEED points. In Boulder, Colorado, for instance, bicycle storage and showers for employees are a requirement for any office development, and good connections to the city’s network of bike trails are important for approval and marketing.

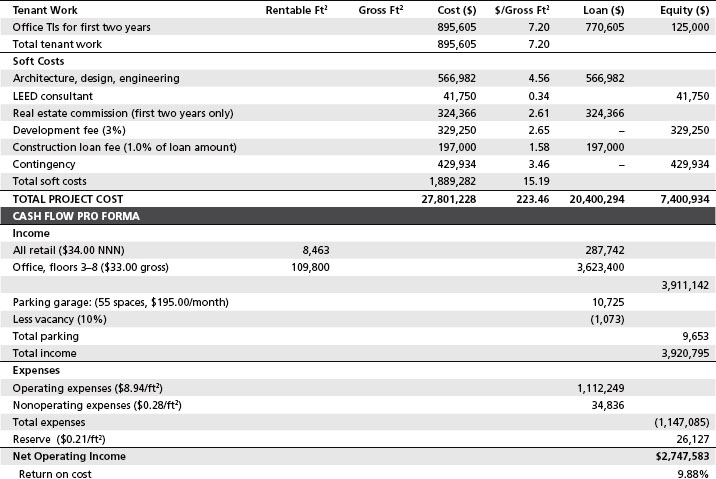

The financial feasibility process involves gathering market data from the market study, cost data for various alternatives, and financing costs and entering these data into the financial pro forma. Developers should also consult local mortgage brokers and lenders to determine current appraisal and underwriting criteria before considering a project.

Two useful sources for estimating local operating costs for office buildings are the Experience Exchange Report published by BOMA International and the income/expense Analysis for office Buildings published by IREM. Both reports are published annually with a detailed breakdown of operating costs and revenues for different types and sizes of office buildings across the United States. The Studley Effective Rent Index report is another source of aggregate operating cost information for Class A office properties in selected downtown and suburban areas.

The key to accurately estimating revenues for office projects is to make realistic projections regarding lease-up time, vacancy rates, and achievable rents. Developers can apply the SFFS (simple financial feasibility analysis) methodology outlined by Geltner and colleagues26 as an assessment tool for their go/no-go decision. Financing for Real Estate Development27 is also a good reference on financial feasibility.

Capitalization rates (cap rate = net operating income/property value) are very important in underwriting because a project’s debt capacity is a function of its value. Cap rates reflect variable market conditions over time, with low levels indicating a strong market versus high levels that indicate weak markets.

Developers should always be prepared for possible cap rate increases during construction and until stabilized occupancy is achieved for two reasons: (1) If the cap rates increase, the value of the property decreases and the lender can request the value difference from the developer, which can be substantial depending on the equity structure. If the developer cannot infuse equity or negotiate a deal, the lender can foreclose (worst case scenario). (2) Refinancing an asset in a period of increasing cap rates is difficult because of the additional equity infusion required by lenders.

The key to any successful design is to address the area market and building codes and offer an efficient building at an appropriate price. Among the major design decisions are the shape of the building, design modules, bay depths, type of exterior, and lobby design, all of which create an image and identity for the structure.

Office buildings also need to be adaptable and flexible to meet the shifting demands of tenants for periods spanning more than 50 years. Flexibility is especially important as tenants expand or contract. Tenants are very sensitive to the amount of common areas (for example, lobbies) in a building because they are typically charged for their prorated share of common space in addition to their usable space.

The market analysis should help provide the design parameters for the project, although some design elements, such as the placement of corridors, restrooms, stairwells, and fire walls, are usually dictated by local building and fire codes.

As a general rule, total project costs are broken down into the following percentages:

| Building shell and interior | 45% |

| Environmental and service systems | 25% |

| Land and site improvements | 18% |

| Fees, interest, and contingencies | 12% |

| Total | 100% |

A few comments can be made on the preceding project cost breakdown:

• The percentages differ depending on the project location (downtown versus suburbs), regional requirements, construction methods, and special fees required by local government bodies.

• There is pressure to improve environmental and service systems across the country while decreasing fees and contingencies.

• A rule of thumb is that in urban areas, the site improvements usually do not exceed 10 to 15 percent of total cost.28

• In high-rent districts, land is likely to represent a larger portion of the costs, as much of the increased rent can be attributed to the property’s locational advantages.

• In addition to the project costs above, developers usually expect a profit of between 20 and 25 percent. A profit of around 12 percent for developers will only cover operating costs without any overhead profit.

SHAPE. A square is the most cost-efficient building shape because it provides the most interior space for each foot of perimeter wall. But it often generates the lowest average revenue per square foot because tenants pay for floor area and windows. Rectangular and elongated shapes tend to offer higher rents per square foot but cost more to build because they provide more perimeter window space and shallower bays. Developers prefer rectangular buildings for multitenant speculative space because the interior and perimeter spaces can be more balanced.

Although nonrectangular shapes may be less efficient, they often create more interesting office shapes, more corner offices, and higher rents. Beyond the developer’s and architect’s vision, building shape is influenced by market conditions, environment, land uses, and zoning. In Asia, for example, there is a requirement that buildings avoid casting shadows, which leads to unique shapes and orientations.29

DESIGN MODULES AND BAY DEPTHS. Office buildings are designed using multiple modules, which allow for the repetition of structural and exterior skin materials. Although the design module is most visible on the exterior of the building, it should evolve from the types of interior spaces planned. The market study should suggest the types of interior design (for example, open-plan or executive offices) that are in the greatest demand in the target market.

The most common design module is the structural bay. Defined by the placement of the building’s structural columns, the structural bay is generally subdivided into modules of four or five feet (1.2 or 1.5 m) with the most common module being 4.5 to 5 feet (1.3–1.5 m), which provide a grid for coordinating interior partitions and window panels for the exterior curtain wall.30 In Europe and Asia, 3 feet 11 inches (1.2 m) and 5 feet (1.5 m) are the most common.31 The structural bay determines the spacing of windows, which in turn determine the possible locations of office partitions, ascertaining whether interior space can be easily partitioned into offices of eight, nine, ten, 12, or 15 feet (2.4, 2.7, 3, 3.6, or 4.6 m) (see figure 5-5).

Office width tends to respond to local market conditions, with the market analysis providing some guidelines. Typically, offices are 10 to 14 feet (3–4.3 m) deep, and hallways are five to six feet (1.5-1.8 m) wide. For example, private office space in Chicago is 10–15 feet (3–4.6 m) wide, whereas in Atlanta it is only 8–12 (2.4–3.6 m).32

The bay depth is typically 40 to 45 feet (12–13.7 m).33 Multitenant buildings with many small tenants require smaller bay depths—36 feet (11 m)—to permit a larger number of window offices. Institutional users, on the other hand, prefer 40- to 50-foot (12–15 m) bay depths, which are more efficient to build and tend to cost less. One alternative is an asymmetrical design, with the core offset to allow flexibility in marketing and layout. The bay might be 40 feet (12 m) deep on one side of the core and 50 to 60 feet (15–18 m) on the other.

Institutional users are more likely to prefer open-space plans, while design and media firms prefer exposed mechanical systems, open ceilings, and partition-free floor-to-ceiling spaces. Large bay depths offer an advantage in such a layout while providing greater flexibility in laying out workstations, whereas a few, if any, private offices require prime perimeter locations.

Developers should keep in mind that at least 12 percent of the floor plate will be occupied by mechanical equipment. And depending on the type of tenant and zoning allowances, the floor plate may increase to 20 percent.34

CEILING HEIGHTS. Floor-to-floor heights are typically between 11 and 14 feet (3.6–4.2 m). In areas where the height of the building is not constrained by zoning or other codes, Class A properties’ floor-to-floor heights may be 14.5 feet (4.4 m). In Asia, the most common heights are between 13 and 13.6 feet (3.9–4.1 m), while smaller concrete buildings—especially in Europe—are 12.4 feet (3.7 m).35

A building’s curb appeal is significantly influenced by its location on its site. Generally, a building should enjoy maximum exposure to major streets, and signage should be visible from those streets. Good site planning provides a logical progression from the street to the parking to the building’s entrance. The trip from the car to the entrance of the building gives visitors and prospective tenants their first impression of the building.

PARKING. In theory, an office building in which each employee occupies an average of 250 square feet (23 m2) needs four parking spaces per 1,000 square feet (95 m2), assuming that all employees drive separate cars. The typical area required for each car is 300 square feet (27.8 m2) for surface parking (which includes parking space and driveway) and up to 400 square feet (37 m2) for structured parking to include allowances for ramps.36 When workers carpool or take public transportation, the parking requirement is reduced. Specialty space, such as medical offices, generates more visitors and may increase the need for parking.

Lenders prefer at least four parking spaces per 1,000 square feet (95 m2) of rentable space, even though local zoning may require less. According to John Thomas of Ware Malcomb Architects, many developers reduce the parking ratio as a project becomes larger.37 For example, developers commonly provide four parking spaces per 1,000 square feet for the first 250,000 square feet (23,235 m2) but then provide only two parking spaces for each additional 1,000 square feet (95/m2). Experienced developers, however, cite inadequate parking as one of the most common flaws in attracting and holding tenants.

FIGURE 5-5 | Relationship of Module to Interior Office Size

For Gabe Reisner of WMA Engineers, the cost differential between below- and above-grade parking is not always substantial because parts of the below-grade structure can include mechanical systems, which will free a portion of leasable aboveground space. The cost of below-grade parking depends on the number of below-grade levels, water table elevation, and foundations for adjacent structures. According to Mike Sullivan of Cannon Design, the first level of a below-grade parking structure costs on average $30,000 per parking spot, but the cost doubles for each level below that.38

Some developers have presold their garage structures, raising a significant portion of the construction cost, while the cost to the tenants is a function of the market.

LANDSCAPING. Landscaping is critical to a project’s overall appearance and value. Landscape design can tie diverse buildings together, define spaces, and form walls, canopies, and floors. Concealing, revealing, modulating, directing, containing, and completing are all architectural uses for plants. Landscaping elements not only include vegetation—trees, shrubbery, ground covers, and seasonal color—but also rocks, streams, retaining walls, trellises, and paving materials. Landscaping may be used to control soil erosion, mitigate sound, remove air pollutants, control glare and reflection, and serve as a wind barrier.

Landscape costs must be assessed with the landscape architect during design. A reasonable landscape budget accounts for 1 to 2.5 percent of total project costs, although the cost might be much less in urban areas.

Preserving existing trees can improve a project’s image, assist with marketing efforts, and increase the project’s long-term value. Mature trees can easily be destroyed, however, if precautions are not taken during construction.

Exterior design concerns such aspects as exterior building materials, signs, and lighting. A building’s exterior design can be an invaluable marketing tool.

BUILDING MATERIALS. The building materials used are generally part of two distinct systems: the structural system and the skin system. The structural system supports the building, and the skin protects the interior space from the weather. An office building can be built using one of six structural systems:

• Metal Stud Frame—Generally used for one- to five-story buildings;

• Concrete Tilt-Up—Generally used on one- to three-story buildings and typically employed in flex buildings;

• Steel Frame with Precast Concrete (hollow-core planks)—Typically used for low-rise buildings;

• Reinforced Concrete—Used for both low- and high-rise buildings;

• Steel—Used for both low- and high-rise buildings; and

• Composite Structures (steel gravity framing with concrete core)—Used in high-rises and superstructures.39

The exterior of an office building can be covered with any number of materials:

• Exterior Insulation Finish System—Synthetic stucco formed in many shapes;

• Precast Concrete—Usually cast off site and shipped to the site and usually not part of the structural system;

• Tilt-Up Concrete Panels—Cast on site and used as part of the structural system, limited to three stories (most common in the suburbs, although panels have very limited utility in office buildings due to glazing limitations);

• Glass Curtain Wall System—A combination of vision and spandrel glass hung in front of the building frame (always used on Class A properties);

• Storefront System (two-story height limit);

• Metal Panels—Aluminum or steel finished in a factory;

• Stone—Granite, marble, or slate in large panels or small tiles; and

• Residential Materials—Including stucco and brick, used as exterior cladding materials and not as a wall system.40

Each structural system can be combined with another to produce economical hybrids, such as a masonry building with metal trusses or prestressed concrete floor units. Concrete tilt-up construction offers an advantage in that the concrete panels serve as both the structural system and the skin (see figure 5-6). Exterior materials can also be combined; for example, a tilt-up building might incorporate a storefront system or precast elements for architectural variety.

SIGNAGE. Signs identify a building and its tenants while creating an overall impression for visitors. Although tenants will negotiate for sign privileges, developers should retain sign approval as a condition in their tenants’ leases. Restrictions should stipulate the size, shape, color, height, materials, content, number, and location of all signs.

The developer’s architect should work with graphic and interior designers to create a signage program for individual tenants and for interior and exterior common areas. The best approach is to develop a comprehensive signage program that includes designs, materials, and color schemes for the following purposes:

• project identification at the entry to the development;

• building identification;

• directory of major occupants;

• directional signs for vehicular and pedestrian traffic;

• building location directories; and

• interior building service signs.

Some developers hire a single sign maker to coordinate the signs for an entire project allowing for expedited replacements and changes. The system for doorplates should allow for easy replacement of old signs when tenants change. Coordinating the installation of signs is the responsibility of the on-site building manager.

EXTERIOR LIGHTING. Exterior lighting can enhance the security of building entrances and parking lots and can highlight architectural and landscaping features. Inadequately illuminated areas may pose a liability problem. The developer should work with an electrical engineer and architect to design exterior lighting that will accomplish the desired effects while being energy efficient and easy to maintain. Mercury- or sodium-vapor, quartz, LED (light-emitting diode), and fluorescent lights are energy efficient and may be used in exterior lighting fixtures. Many jurisdictions have become concerned about light pollution, and they require the use of high-cutoff lights and limit the use of architectural illumination that lights the sky.

Lighting standards for parking lots should be placed around the perimeter of the lot or on the centerline of double rows of car stalls. The Illumination Engineering Society recommends a minimum illumination level of 0.5 to two foot-candles for outdoor parking areas and five foot-candles for structured parking.

The interior design must accommodate all the various systems—elevators; plumbing; heating, ventilation, and air conditioning (HVAC); lighting; wiring; and life safety—and provide a flexible core and shell, which are very important in attracting tenants. The use of modular systems (flexible walls or partitions) is increasing because of their flexibility to meet tenants’ changing needs.

Another boon to flexibility is the use of raised floors, which are typically four to six inches (100–150 mm) above the concrete slab,41 allowing data cabling, mechanical systems, and power to be configured easily. Even though they have an upfront cost, the operating cost savings over time, human comfort, and sustainability can outweigh the cost.

MEASURING SPACE. Multiple local and national measurement standards of office buildings exist (gross, rentable, and usable square feet), with BOMA International standards being widely used. There are three key measurements:

• Gross area is measured from the exterior walls of the building without any exclusion (basements, mechanical equipment floors, and penthouses).

• Rentable area is measured from the inside finish of the permanent outer walls of a building except vertical penetrations (elevators, stairs, equipment, shafts, and atriums). According to local definitions, it may also include elevator lobbies, toilet areas, and janitorial and equipment rooms.

• Usable area is measured from the inside finish of the outer walls to the inside finished surface of the office side of the public corridor. Usable area for full-floor tenants is measured to the building core and includes corridor space. An individual tenant’s usable area is measured to the center of partitions separating the tenant’s office from adjoining offices. Usable area excludes public hallways, elevator lobbies, and toilet facilities that open onto public hallways.

The tenant’s rentable area is derived by multiplying the usable area by the rentable/usable ratio (R/U ratio). The R/U ratio is the percentage of space that is not usable plus a pro rata share of the common area. For example, if a tenant rents 1,000 square feet of usable space in a building with a 1.15 R/U ratio, the tenant pays rent for 1,150 square feet:

Usable square feet × R/U = Rentable square feet

1,000 usable square feet × 1.15 = 1,150 rentable square feet

Tenants are very sensitive to the R/U ratio, often referred to as the building efficiency ratio, core factor, or load factor. The average R/U ratio for high-rise space is about 1.15. Low-rise space averages around 1.12. Developers with inefficient buildings (with R/U ratios greater than 1.2) sometimes arbitrarily reduce the ratio to make their buildings appear competitive. Developers should be careful to calculate pro forma project rental income on the actual rentable area and not on the gross building area, which is more appropriately used to estimate construction costs.

FIGURE 5-6 | Exterior Skin Materials

SPACE PLANNING. Effective space planning involves five basic components: the space itself, the users, their activities, future uses, and energy efficiency.

The amount of space and its functionality are controlled by a building’s exterior walls, floors, ceiling heights, column spacing and size, and the building core.

In a single-tenant building or a floor tenant, the tenant is responsible for improving the lobby and interior hallways. In a multitenant building, however, the developer improves the lobby, restrooms, and hallways that serve each suite, and individual tenants are responsible for their own suites.

Many modern office layouts use the open-space planning approach, which helps reduce the cost of initial construction and design changes. Partitions in open-space plans are movable, and a variety of furniture and wall systems are available that are attractive and use space efficiently.

An inviting lobby with an identity is critical in attracting perspective tenants even if it comes with a premium for the developer. Restrooms likewise can help recover high-quality decoration costs because both tenants and visitors use them.

ELEVATORS. Tenants’ and visitors’ initial impressions are shaped by a building’s lobby and the quality of the interior finish of elevator cabs. Finish materials used in the lobby—such as carpet, granite, marble, brass, and steel—can also be used effectively inside the elevator.

Elevator capacity depends on the kinds of tenants occupying the building. Buildings occupied by larger companies tend to need high-capacity elevators to accommodate peak-hour demand. Buildings with smaller companies tend to have lower peak-period demand because more tenants keep irregular hours; but professional tenants are more conscious of time lost waiting for elevators. Waiting time for elevators should average no more than 20 to 30 seconds; longer waits can affect a tenant’s lease renewal decision.

The following rules of thumb are useful for gauging elevator capacity:

• One elevator is needed per 40,000 square feet (3,700 m2).

• One elevator is needed for every 200 to 250 building occupants (for two- to three-story buildings the demand will be lower).42

• Buildings with two floors require one or two elevators, depending on the nature of the local market and the size of the floors.

• Buildings with three to five floors require two elevators.

• Ten-story buildings need four elevators.

• Twenty-story buildings need two banks of four elevators.

• Thirty-story buildings need two banks of eight elevators.

• Forty-story buildings need 20 elevators in three banks.

Many elevator control innovations are being used in high rises, such as kiosks where riders indicate the floor of preference and the system directs them to the faster elevator (grouping riders to various floors), significantly increasing the speed and capacity of the system.

Some very large office buildings—especially in downtowns of major cities—feature escalators in their main lobbies.

LIGHTING. Lighting plays a critical role in how users and visitors perceive the building. The 2007 adoption of the Energy Independence and Security Act meant the phasing out of incandescent bulbs between 2012 and 2014. Owners of existing buildings or developers retrofitting a property can benefit from the energy-efficient commercial buildings tax deduction, which can also be used to write off the indoor lighting retrofit cost.

Several types of artificial light are available for interior applications:

• Fluorescent—Fluorescent fixtures are expensive but have the advantage of long bulb life (18,000 to 20,000 hours) and reduced energy consumption. Under the 2007 energy legislation, T12 lamps will be replaced by more efficient T8 or T5 lamps.

• Light-Emitting Diode—LED fixtures are becoming increasingly common. LED bulbs have a long life (25,000 to 100,000 hours) and vastly reduced energy consumption.

• Incandescent—Incandescent fixtures are less costly than fluorescent fixtures but are more expensive to operate. They provide superior color rendering but a short bulb life (750 to 2,000 hours). They are scheduled to be phased out beginning in 2012.

• High-Intensity Discharge—High-intensity discharge lighting includes mercury-vapor (frequently used outdoors), metal-halide, and high- and low-pressure sodium lamps. Although they are excellent for illuminating outdoor spaces and are very energy efficient, high-intensity discharge lights offer poor color-rendering properties.

• High-Intensity Quartz—Sometimes called precise lighting, high-intensity quartz lighting is a new product that is often used in upscale environments. Multifaceted, mirrored backs reflect the light onto specific objects or areas, making high-intensity quartz fixtures appropriate for task-oriented lighting.

Office buildings use mainly direct lighting. Installed in a grid pattern across a dropped ceiling, this solution offers equal levels of illumination across large spaces. Direct lighting is available in integrated ceiling packages, including lighting, sprinklers, sound masking, and air distribution. Indirect lighting uses walls, ceilings, and room furnishings to reflect light from other surfaces. In recent years, indirect lighting has become common for general office lighting as a way to reduce glare on computer monitors. Indirect lighting generally requires higher ceilings to reduce “hot spots” on ceilings and to improve the overall efficiency of the lighting layout.

The electrical engineer, interior designer, and architect all play important roles in designing the lighting system to suit each tenant’s needs.

HEATING, VENTILATION, AND AIR CONDITIONING. A building’s HVAC system is one of the major line items in its construction and operation budget. Several different types of HVAC systems are available:

• Package Forced-Air Systems—These electrical heat pumps, usually located on the roof, heat and cool the air in the package unit, then deliver it through ducts to the appropriate areas of the building. The units are inexpensive to install and work well on one- and two-story buildings.

• Variable Air Volume Systems—A large unit on the roof cools the air and delivers it through large supply ducts to individual floors. Mixing units control the distribution of the air in each zone. This system offers great flexibility as many mixing units can be installed to create zones as small as an office, but it is more expensive to install than forced-air systems. The system allows for balance loads and automatically adjusts airflow. Rooms are heated by a heating element in the mixing units or by radiant heater panels in the ceiling.

• Hot- and Cold-Water Systems—A combination chiller and water heater is centrally located to provide hot and cold water to the various mixing units in the building. The air is heated or cooled in these mixing units and delivered to the local areas.

RBC Centre is a 43-story office tower in Toronto’s financial district. The development earned LEED Gold status and will produce an estimated 50 percent energy savings relative to the Canadian National Energy Code.

TOM ARBAN

The architect and mechanical engineer will provide guidance in the selection of the HVAC system. For a development of about 100,000 square feet (9,300 m2)—four to five stories of 25,000 square feet (2,300 m2) of floor plate—the most economical system is a rooftop variable air volume system, but in some markets heat-up systems are more common. LEED can be achieved with either. The capacity of the system will be determined by several factors, including climate, building design, and types of tenants.

The American Society of Heating, Refrigerating and Air-Conditioning Engineers (ASHRAE) publishes standards on the minimum ventilation rate for different occupancy and building types, relative humidity, and maximum allowable air velocity. Poor humidity control and leaks in a building can cause sick building syndrome, which exposes building owners to possible lawsuits. ASHRAE’s Humidity Control Design Guide for Commercial and institutional Buildings43 provides guidance on humidity control to the entire building team. The final authority on building ventilation is the local code authority, which may or may not have adopted ASHRAE standards. Standards for air movement and air conditioning depend on building design, climate, glazing, lighting, and building orientation.

Computer-controlled systems manage energy use of medium-sized or large buildings. A well-designed HVAC system divides the building into zones, each controlled by a thermostat. These zones should cover areas with similar characteristics, such as orientation to the sun, types of uses, and intensity of uses. A standard rule of thumb is one thermostat zone per 1,200 square feet (110 m2). Usually, each zone has one mixing damper that controls temperature by mixing hot and cold air.

TECHNOLOGY. Technology is changing the economics of office buildings in a variety of ways:

• Design—Building Integrated Modeling/Revit (BIM/Revit) is in the forefront of virtual coordination by facilitating complex design among mechanical, electrical, and plumbing systems. BIM allows the construction phasing to be better coordinated while providing a comprehensive data record for the operations management phase.

• Energy Sustainability—Buildings are consuming less energy with the help of low-E glass, external shading, automatic dimmers, and motion sensors. Some buildings are even producing energy with smart grid system and solar panels.

• Water Conservation and Reuse—Water system controls are becoming more sophisticated. Automatic faucets, low-flow toilets, rainwater harvesting, waterless urinals, and use of graywater for flushing toilets, landscape watering, and other nonpotable uses are increasingly part of the conservation effort.

• “Smart” Buildings—All building systems are integrated into one network, which allows the efficient control of life safety and security, building management, elevators, office telecommunication, and HVAC systems on site or remotely.

• New Revenue Sources—Every part of the office building is being examined for the potential to generate revenue. For example, income can be generated from communications towers mounted on roofs, from signage in highly visible locations, and from recycling waste materials, such as office paper.

• Maintenance Costs—Mechanical rooms are kept cleaner, with filters changed more often and air monitored. Recycling chutes in high-rise buildings eliminate the need for recycling bins on every floor.

ENERGY EFFICIENCY. A building’s energy efficiency depends on its site orientation, skin materials, window design, and types of mechanical equipment and energy control systems. Energy costs can decrease by investing up front in continuous building envelopes that do not provide thermal bridges. The energy efficiency of the exterior facade can be improved with active and passive shading systems and other thermal technologies, while harvesting rainwater and daylight. For example, a rain-screen wall is a pressure-equalized system with minimum operational maintenance cost, although there is an upfront cost.44

A popular way to measure energy efficiency is the U-value, which measure the rate of heat loss expressed in Btus per hour per square foot per degree difference between the interior and exterior temperatures. The U-value is the reciprocal of the total resistance of construction multiplied by a temperature or solar factor. As a general rule, U-values should be a minimum of 0.09 for insulated exterior walls and 0.05 for insulated roofs. The architect and mechanical engineer can provide recommendations for insulation.

Glass reflection plays an important role in determining energy use and is measured as the shading coefficient, which equals the amount of solar energy passing through glass divided by the total amount of solar rays hitting the glass. The lower the coefficient, the larger the amount of heat reflected away from the building’s interior. Lower shading coefficients tend to be more expensive to obtain and adversely affect the quality of light for building occupants. Many state and local government agencies have their own energy-efficiency requirements.

Numerous energy-related incentives are offered by government and nongovernment organizations. Two relatively new initiatives are the application of demand response mechanisms on buildings, which help manage energy use based on electricity grid supply conditions, and smart grid systems, which allow for two-way communication between consumers and utility companies. For Mike Munson of Metropolitan Energy, the smart grid system is simply a tool to transfer information.45 Smart grid systems enable building owners and managers/engineers to make better decisions about their building’s energy use. Munson notes that for new construction, the ability to optimize a building’s operational flexibility and to maximize the control of building systems with precision enables greater certainty and increases asset value by building control capabilities from the ground up. For existing buildings, the ability to acquire, process, and implement solutions using information provides for more discerning capital and efficiency improvement analyses.

GREEN BUILDING DESIGN. Green buildings can be defined in a variety of ways, but the U.S. Green Building Council’s LEED rating system has become the accepted standard. Green buildings accomplish reduced energy consumption by improving natural light penetration, using more efficient HVAC systems, and relying on more sustainable building materials.

Certain LEED points can be achieved inexpensively (for example, bicycle racks, showers, and transit subsidies), but long-term savings require the use of additional base building systems controls, such as heat exchangers, displacement air systems, double-wall systems, active shading systems, and so forth, which have an upfront premium. By adopting multilayered energy systems, the building can circulate air more effectively based on different situations and can synchronize electric lighting with daylight using lighting controls.

In cases where structures need to be demolished or rehabbed, disposing of the old materials in an environmentally friendly way can be difficult and costly. According to Tom McCaslin and John Wong of Tishman Construction Corporation, which built Four Times Square, New York City’s first green office tower, green buildings generally cost more to construct, although the initial cost can be recovered later through energy savings. A green building can also generate good publicity and promote the firm as environmentally friendly with some tenants willing to pay rental premiums.46 Four Time Square used several energy conservation features, including photovoltaic panels, fuel cells, gas-fired absorption units, and low-noise air handlers.47