Franke Corporate Headquarters and Distribution Center, Smyrna, Tennessee.

© 2009 JIM ROOF CREATIVE INC.

In addition to design and construction of buildings, industrial development involves site planning, subdivision design and platting, and the construction of utilities and internal streets. Consideration must be given to access, parking, building design, and landscaping. In recent years, green building practices have become increasingly important in the development, design, and construction of industrial facilities, and understanding this process is becoming a prerequisite for a successful project.

Beginning developers may start out with a building for lease or a site that is suitable for one or more industrial users. If a build-to-suit tenant or buyer has not been pinned down, they might proceed with a speculative building that can be leased or sold in the future. Depending on market conditions, more profit can potentially be made on a speculative building than on a build-to-suit project because negotiations over lease terms with a potential major tenant can be tough. Speculative buildings are much harder to get financed, however. Construction lenders typically will not proceed unless the developer has deep pockets, with other collateral available, and is willing to sign personally on the loan. The economic difficulties generated by the Great Recession have made it more difficult for the small independent industrial developer to get access to capital.

Consolidation of small industrial developers has been occurring, along with a higher degree of specialization, and small developers are occupying niches that large companies are unable or unwilling to fill, in some cases, playing a support or supplementary role to larger firms. Beginning industrial developers should be wary of some possible pitfalls:

• paying too much for land or capital;

• underestimating the amount of competition;

• building the wrong product for the market, which can usually be avoided by involving the right consultants in the development process from the beginning;

• using an architect who has no experience in the type of product being designed; developers should find someone who knows the local market; can provide a market-oriented, functional design; and knows how to maximize its flexibility; and

• not properly engaging local stakeholders in the entitlement process.

Business parks offer developers the flexibility to sell unimproved land parcels or completed buildings. Generally, they are completed in phases, which helps minimize risks associated with changing market conditions. Today’s business parks are the product of an evolutionary process that had its antecedents in the manufacturing-oriented industrial estates and parks of the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

The first business parks appeared in the 1950s and were focused on office rather than industrial uses. The 1960s saw the advent of specialized R&D parks that benefited from links between universities and business. These settings combined a variety of functions, from offices to laboratory research to light manufacturing. Light industrial uses, such as manufacturing and warehouse/distribution facilities, are still integral parts of many business parks today, but the proportion of office space and such newer uses as call centers is growing. Heavy industry, once a significant element of planned industrial districts, is seldom included. Economies have shifted away from heavy manufacturing, and communities concerned about environmental impacts prefer lighter, higher-tech businesses as employment generators. Zoning often restricts the location of heavy industry in business parks and closer-in areas, whereas at the same time, large manufacturing companies generally prefer to locate at stand-alone sites farther outside the city where land is cheaper.

Today, business park locations tend to be in suburban areas with freeway and airport access. Proximity to housing, shopping, cultural amenities, and educational facilities is sometimes important, depending on the types of uses being targeted. older inner-city industrial sites with good freeway access are becoming attractive again because of the availability of existing buildings and infrastructure at infill locations.

An industrial building is defined by the National Association of Industrial and office Properties as “a facility in which the space is used primarily for research, development, service, production, storage, or distribution of goods and which may also include some office space.”

All types of industrial properties have common characteristics despite variations in functions and use. Three primary categories of buildings are typically used to categorize industrial real estate: manufacturing, warehouse, and flex. Within these categories are a variety of subcategories that have distinctive physical characteristics to accommodate specialized functions.1 These buildings may be located in industrial areas or master-planned business parks, or they may be stand-alone structures. The typical building characteristics of the three primary industrial building types are shown in figure 6-1. This matrix illustrates the spatial configurations of the various industrial building types and the relationship of the subcategories to each primary category.

FIGURE 6-1 | Typical Industrial Building Characteristics by Type

More specialized subsets exist within the categories. For example, within “manufacturing” is a further breakdown of “heavy and light” classes. Within “general-purpose warehouse” exists “bulk warehouse, cold/refrigerator storage, freezer storage, high cube, self-storage, and bonded.”

MANUFACTURING. Manufacturing structures are large facilities designed to accommodate the equipment for manufacturing processes. Light manufacturing buildings can be up to 300,000 square feet (27,880 m2); heavy manufacturing buildings are more than 1 million square feet (93,000 m2).

Floor-to-ceiling heights range from 10 to 60 feet (3–18.3 m) and average 20 to 24 feet (6-7.3 m). Large bay doors with at-grade or dock-high parking for large trucks and ample room for trucks to maneuver are usually a necessity. With the exception of assembly-related facilities, parking ratios vary—as low as 1.5 parking spaces per 1,000 square feet (95 m2) of building area, depending on the planned number of employees. Because of their minimal parking requirements, traditional industrial buildings frequently cover 25 to 45 percent of a site (FAR).

The development of heavy manufacturing facilities has slowed considerably since the mid-20th century, their place taken by clean light manufacturing industries that have contributed significant demand for new industrial space. Because they focus on technology-based activities, these industries typically produce fewer of the undesirable side effects that limited the location of the older heavy industries.

Manufacturing facilities are often designed specifically for a company’s manufacturing process. Consequently, few tenants are interested in taking over another company’s manufacturing facility. Nevertheless, these manufacturing plants often have special equipment, such as heavy-duty cranes, that some companies find very valuable. Once a new tenant is found, it will likely stay there longer because of the specialized design and equipment.

WAREHOUSE. Warehouse buildings focus on the storage and distribution of goods. Within the category are three major subtypes of facilities: general-purpose warehouse, general-purpose distribution, and truck terminal. Some differences exist in these types in their size, ceiling heights, and loading requirements, but in general, they have similar requirements: large, flat sites with space for maneuvering trucks and access to transportation facilities.

Warehouse buildings have low employee-to-area ratios—typically one or two employees per 1,000 square feet (95 m2). As a result, only a small amount of employee parking is needed. Most warehouses have a minimal amount of office space—5 to 10 percent of total floor area. In some buildings, however, as much as 10 to 20 percent of the area may be allotted to office uses, chiefly to accommodate the purchasing, accounting, and marketing staff of a distribution or manufacturing company. Typically, these buildings have an attractive front elevation with ample windows for the office portion of the building and provide good truck access to the rear or side of the building. Dock-high and/or drive-in doors are provided to serve the warehouse functions.

In recent years, clear height, also referred to as “clear headway,” which is the distance from the floor to the lowest hanging ceiling member, of warehouse buildings has increased from 26 to 28 feet (8–8.5 m) clear to 32 feet (9.7 m) or more clear at the first perimeter bay where stacking does not usually occur. The clear height then increases as the roof slopes upward toward the center of the building to a clear height of 40 feet (12 m) at its highest point. The extra clearance provides room for higher stacking. Plentiful truck bays, preferably on opposite sides of the warehouse, are critical for moving merchandise in and out, as the added value for bulk warehouses is the ability to move goods faster with minimal storage time.

Warehouse/distribution buildings have become substantially larger than they were two or three decades ago. Previously, buildings of 400,000 square feet (37,175 m2) were considered large. In the early 2000s, spaces from 750,000 to 800,000 square feet (70,000–74,350 m2) are being occupied by single tenants. one reason behind the demand for larger spaces is the consolidation of distribution businesses. Many sophisticated third-party logistics companies now handle transport of merchandise and parts for other companies.2

Some communities oppose the development of warehouses because they bring lower tax benefits and more truck traffic than other types of industries. on the other hand, such buildings generate relatively little daily automobile traffic and can be attractively landscaped.

FLEX. As its name suggests, flex space is industrial space designed to allow its occupants flexibility of alternative uses of the space, usually in an industrial park setting. Flex buildings are typically one- or two-story structures ranging from 20,000 to 100,000 square feet (1,860–9,295 m2). The pattern for internal uses has been about 25 percent office space and 75 percent warehouse space, but this proportion is changing in favor of more office space in many markets. External designs are generally clean, rectangular shapes with an abundance of glass on the front facade. Building depths vary, so developers need to understand the market to determine the best configuration.

Specialized R&D flex buildings fall into two distinct categories. one category includes facilities in which research is the primary, or only, activity. Design of the interior spaces is frequently unique to the specific research that will be carried out there. The other type of R&D building is intended to serve multiple uses. This type of structure, which may have one or two floors, often has office and administrative functions in the front of the building and R&D or other high-tech uses in the rear.

Offices in R&D buildings typically have open floor plans to promote teamwork and collaboration, and to facilitate easy rearrangement of spaces and furniture for rapidly changing work groups. Many tenants are small startup companies; others are subsidiaries of major corporations. Activities range from the creation and development of new technologies and products to the development, testing, and manufacture of products from existing technology.

The design of tenant improvements is more important for R&D uses than for other industrial uses and is usually tailored to the needs of specific tenants. The percentage of space allocated to laboratories, research offices, service areas, assembly, and storage varies widely. Hard-to-rent space in the center of buildings is well suited for laboratories and computer rooms where environmental control is critical.

MULTITENANT. Multitenant buildings cater to customer-oriented smaller tenants, such as office, showroom, and service businesses, that require spaces of 800 to 5,000 square feet (75–465 m2). The buildings are generally one story, with parking in the front and roll-up doors in the rear for truck loading. They provide parking ratios of two to three spaces per 1,000 square feet (95 m2) and turning radii in loading areas that are large enough for small trucks. Leased spaces are built so that they can be divided into modules as small as 800 square feet (75 m2). Frequently, 25 to 50 percent of the interior is improved, leaving the balance of the building as manufacturing, assembly, or warehouse space.

The LEED Silver-certified Franke Corporate Headquarters and Distribution Center occupies about 40 acres (16 ha) near the Smyrna, Tennessee, airport. The site includes a warehouse and a two-story corporate office and research center.

© 2009 JIM ROOF CREATIVE, INC.

Some developers build all the tenant improvements for a project along with the base building, whereas others initially build just the shell and wait to build tenant improvements as space is leased. The first method limits flexibility and increases upfront costs; the second can be expensive if materials for tenant improvements cannot be bought at bulk prices. Methods for building tenant improvements frequently depend on a project’s marketing scheme and anticipated absorption rate.

Exterior designs vary. Some markets require an upscale look that can be supported only by higher rents. In other markets, multitenant buildings are considered economy space so the most cost-effective combination of construction materials is used.

OFFICE/TECH. office/tech buildings are used primarily for office space. They may provide limited truck access and warehouse facilities. Users of such buildings generally look for large volumes of space to house employees and have only limited interest in space for laboratories or computer facilities. Large paper processors, such as insurance companies and banks, require large office spaces and desire low rental costs for their back-office functions; hence, they prefer the cost advantage and efficiency of office/tech industrial buildings. High parking ratios—such as three and one-half to four spaces per 1,000 square feet (95 m2) of net rentable area—are important to office/tech users.

FREIGHT. Freight facilities are not always included as a category of industrial real estate, but they are increasingly important in supply chain management. The freight-forwarding processes involving the transfer of goods from trucks to trucks and from planes to trucks require specialized buildings, each of which has special requirements for loading capabilities, building configurations, and space buildout.

TELECOMMUNICATIONS. Two types of telecommunications facilities have emerged since the late 1990s: data warehouses and switch centers. These types of buildings can be developed through the conversion of an older building that has access to fiber-optic cable or the construction of a new building solely for telecommunications use.

Business parks are multibuilding developments planned to accommodate a range of uses, from light industrial to office space, in an integrated park-like setting with supporting uses and amenities for the people who work there. They can range in size from several acres to facilities of several hundred acres or more.

Most business parks offer a conventional mix of warehouses, flex space, and offices to meet the needs of a range of occupants. Over the past 25 years, however, more specialized types of business parks have emerged. Although each of them can be categorized by a distinctive function and design characteristics, product types and their users overlap considerably. The primary categories include the following:

• Industrial Park—Modern industrial parks contain large-scale manufacturing and warehouse facilities and a limited amount of or no office space. The term industrial park connotes a setting for heavy industry and manufacturing, but it is still sometimes used interchangeably with business park.

• Warehouse/Distribution Park—Warehouse and distribution parks contain large, often low-rise storage facilities with ample provisions for truck loading and parking. A small portion of office space may be included, either as finished space built into the storage areas or housed in separate office structures. Landscaping and parking areas are included, but because of the relatively low ratio of employees to building area, on-site amenities for employees tend to be minimal.

• Logistics Park—Such business parks focus on the value-added services of logistics and processing goods rather than warehousing and storage. As centers for wholesale activity, they may also provide showrooms and demonstration areas to highlight products assembled or distributed there.

• Research Park—Also known as R&D and science parks, research parks are designed to take advantage of a relationship with a university or government agency to foster innovation and the transfer and commercialization of technology. Facilities are typically multifunctional, with a combination of wet and dry laboratories, offices, and sometimes light manufacturing and storage space. Biomedical parks are a specialized version.

• Technology Park—Technology parks cater to high-tech companies that require a setting conducive to innovation. They rely on proximity to similar or related companies rather than a university to create a synergistic atmosphere for business development.

• incubator Park—Incubator parks or designated incubator sections of research or technology parks meet the needs of small startup businesses. Often supported by local communities through their economic development agencies or colleges, they provide flexibly configured and economically priced space and opportunities for shared services and business counseling.

• Corporate Park—Corporate parks are the latest step in the evolution of business parks. Often located at high-profile sites, they may look like office parks, but often the activities and uses housed there go beyond traditional office space to include research labs and even light manufacturing. Supporting uses, such as service-oriented shopping centers, recreational facilities, and hotel/conference centers, are provided as a focus rather than an afterthought.

Older industrial districts offer opportunities to beginning developers, especially underused buildings suitable for rehabilitation and small infill sites. Many communities have established programs to encourage redevelopment of older industrial areas. Redevelopment agencies and economic development agencies may offer incentives such as tax abatement and financing to developers who build in designated redevelopment areas. Renovation of older industrial areas offers many development opportunities:

• upgrading low-tech, light industrial buildings to be competitive with newer facilities;

• redeveloping low-tech, light industrial buildings for higher-tech R&D and office uses;

• rehabilitating major plants, such as outmoded automobile plants, into multitenant warehouses and office/tech buildings;

• removing heavy industrial facilities and reusing the land for business parks; and

• adapting obsolete urban warehouses to commercial, office, and residential uses, which have become increasingly prevalent.

The strong economy of the late 1990s and early 2000s motivated many developers to look at underperforming older industrial buildings for their potential reuse. many of the more easily resolved problem properties have been taken, leaving properties that are likely to have more serious difficulties. Despite these issues, developers have access to a large pool of bargain-priced properties by performing suitable due diligence before buying industrial property.

Some of the potential issues surrounding the rehabilitation of older buildings include cost overruns, title problems, building code problems, poor street and utility infrastructure, and unforeseen construction problems. A major concern that must be addressed is the cleanup of contaminated sites. The answer to which party in the ownership chain is responsible for environmental remediation and what constitutes a suitable cleanup for various planned uses is still evolving.

Reengineering older industrial buildings with historic character is a special challenge. Architectural features should be retained as much as possible, and additions and improvements should be sympathetic with the existing design. New roofing and insulation, new windows with energy-efficient double- or triple-pane glass, the repair and cleaning of exterior wall surfaces, and painting and other cosmetic improvements are common exterior changes. A significant portion of the budget for internal redesign may be required to bring a building up to current fire and safety codes: enclosing stairways, adding sprinklers and fire alarm systems, installing or upgrading new wiring and plumbing, and upgrading or installing the heating, ventilating, and air-conditioning (HYAC) system.

The market analysis that precedes site selection for industrial development serves three purposes: to identify the types of users that will be served, to identify the type of product to be built and thus the parameters of the site to be purchased, and to identify where the product should be located. Just as for office development, the developer should be familiar with basic data about the local economy and its relation to the regional and national picture. The items that should be checked include

• national, regional, and local economic trends;

• growth in employment and changes in the number of people engaged in job categories (as measured by Standardized Industrial Classification codes);

• socioeconomic characteristics of the metropolitan area, including rates of population growth and employment patterns;

• local growth policies and attitudes toward office and industrial development;

• forecasted demand for various types of office and industrial facilities;

• current inventory by industrial subtype;

• historic absorption trends and current leasing activity; and

• historic vacancy rates and current space available.

This information is available from a host of sources, including government and commercial websites, local universities, market analysts, data service firms, chambers of commerce, and major real estate brokerage firms. In addition to evaluating statistics, the developer should consult local brokers, tenants, and other developers to verify the accuracy of the information obtained. A developer who is unfamiliar with the local area should hire a market research firm with experience in industrial real estate.

Few market data sources segment industrial space beyond the categories warehouse/distribution, manufacturing, and flex, and in many cases, secondary market data are lumped into a single category labeled industrial, making it difficult to assess the performance of individual subtypes. one method of obtaining a rough idea of the various property types when the information is not broken down is to segment properties by size categories, such as “under 5,000 square feet” or “larger than 25,000 square feet” (or “under 1,000 m2” or “larger than 2,500 m2”).

Before searching for specific sites, a developer must become thoroughly familiar with industrial development patterns throughout the metropolitan area. During this investigation, the developer wants to learn as much as possible about local market conditions and which types of industrial tenants are expanding or contracting. A developer or industrial company looking for a large, single site is concerned with a number of issues:

• availability and cost of land;

• transportation infrastructure/highway access;

• labor quality and cost;

• tax structure and tax incentives;

• utilities and waste disposal;

• energy rates; and

• comparative transportation rates.

Market preferences, land costs, labor costs, utility costs, and transportation costs can differ dramatically within the same city or region. Companies with markets outside the city have different criteria for site selection from those with markets primarily inside the city. The developer’s market analysis before site selection should assess the target market’s preferences regarding such factors as access to transportation and location.

LOCAL LINKS. Local links are critical to many companies. Firms that have frequent contacts with suppliers, distributors, customers, consultants, or government agencies consider the following in choosing a location:

• accessibility to firms with which they do regular business;

• the number of trips to be made to and from their business inside the metropolitan area;

• congestion in and around the site;

• commuting time for employees and public transportation available; and

• vehicle cost, including taxes, maintenance, and fuel per mile traveled.

CLUSTERING AND AGGLOMERATION. A number of industries—food distribution, garment manufacturing, printing, wholesale flower marts, machinery parts and repair, commercial groceries and kitchen supplies, for example—tend to cluster together. The clustering, known as agglomeration or colocation, often relates to time-sensitive products (such as perishable foods) or to the interdependency of firms in a particular industry. High-tech firms tend to congregate in research parks near major universities, where they can take advantage of resources such as laboratories, libraries, professors and graduate students, and large pools of highly educated and skilled labor. Venture capital is also attracted to universities because of the commercially valuable discoveries they generate.

ACCESS. Access to transportation is fundamental to all types of industrial properties, although requirements vary by type of use. Virtually all industrial uses depend on trucking, so connections to major interstate highway systems are essential. In recent years, the growing “need for speed” in distribution, particularly of high-value goods, has made proximity to highways and airports more important than ever. Although rail service has remained an important factor for some manufacturing and industrial processes, smaller and lighter industrial users depend less on rail accessibility.

Airports exert a strong attraction for industrial users. In many cases, businesses locating near an airport use cargo and passenger services regularly. In other instances, this “airport effect” is the result of good highway access, available land, and favorable zoning.

FOREIGN TRADE ZONES. A foreign trade zone is a site in the United States in or near a U.S. Customs port of entry where foreign and domestic merchandise is generally considered to be in international commerce. Firms located in foreign trade zones can bring in, store, and assemble parts from abroad and export the finished product without paying customs duties until the goods leave the zone. Many foreign manufacturing firms transport their products to a warehouse in the trade zone, store the products until they are ordered by a customer or distributor, and pay the import duties when the product leaves the warehouse to be delivered to the customer. Thus, the firms can have readily available stock without having to pay the associated import fees until the product is actually needed.3

QUALITY OF LIFE. The more intangible factors surrounding quality of life should not be forgotten in site evaluation. Livability is an increasingly important aspect of business location decisions. The presence of affordable housing, quality schools, and recreational and cultural resources strongly influences a company’s ability to attract skilled workers.

Sample Market Analysis for a Multitenant Warehouse

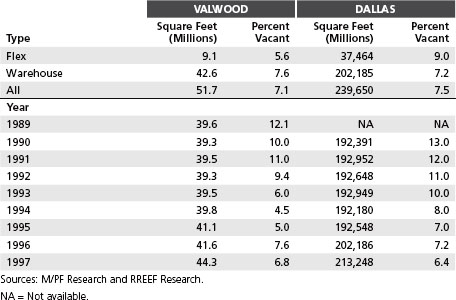

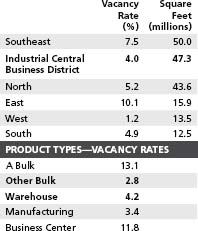

This sample market analysis for warehouse space in Dallas indicates the steps to be taken in a market analysis for industrial properties. In this example, the analysis focuses on the Valwood submarket, a prime location for industrial space in the Dallas, Texas, metropolitan area.

A space inventory for Dallas and the Valwood submarket (figure A) provided a historical sketch of how the submarket has evolved in recent years. At the time of the survey, vacancy rates remained comparatively low, 6 to 7 percent, although some upward movement was obvious in Valwood.

Characterization of submarket rents and lease terms was obtained through a survey of brokers and a review of leasing comparables (figure B). Discussions with brokers also permitted a breakdown to be made of industrial tenants in Valwood by industry group (figure C). The breakdown indicated that rents were at attractive levels and unencumbered by concessions or high tenant improvement allowances.

Projections of warehouse space absorption in the Dallas metropolitan area were based on changes in gross metropolitan product and population. Total employment growth was also considered an indicator of demand in the market. These projections were then used to model metropolitan area warehouse absorption in Dallas. Fair-share capture was used to estimate what share of metropolitan absorption could be captured by the Valwood submarket. The area’s locational advantages suggested a capture rate of 10 to 15 percent in the near term and 15 to 20 percent in the long term. Net absorption in Valwood was estimated to be 9 million to 10 million square feet (836,400–929,400 m2) over the next ten years.

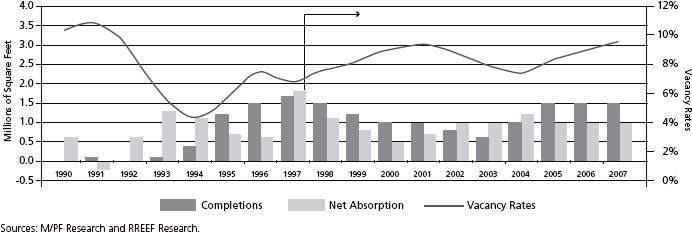

Warehouse space construction in Dallas was found to be occurring in a number of submarkets, including Valwood. Six projects totaling approximately 1.5 million square feet (139,400 m2) were anticipated to be completed in 1998, and another 2 million to 3 million square feet (185,900–278,800 m2) was expected to enter the market in 1999 to 2001 (figure D).

FIGURE A | Space Inventory for Dallas and Valwood

FIGURE B | Warehouse Rents and Lease Terms for Valwood

FIGURE C | Industrial Tenants by Industry in the Valwood Submarket

A final step in the analysis was to present an outlook and a projection of rents for the submarket. To accomplish these tasks, warehouse space absorption and construction volume were compared and measured by projected vacancy rates. These projections showed an upward trend in submarket vacancy through 2001. it was concluded that warehouse construction in valwood would outpace absorption, even though the Dallas economy was expected to expand at a healthy rate. The imbalance in supply was expected to correct itself by 2002 as development activity eased and absorption remained positive, but the threat of continued additions to supply remained a long-term concern.

in light of these trends, submarket rents in valwood were expected to experience only modest growth (figure F). larger properties of 100,000 square feet (9,300 m2) or more were not anticipated to realize any increase in rents, because much of the increase in supply was occurring in this property segment. The near-term prognosis for warehouse space in the under 25,000- and 25,000- to 40,000-square-foot (2,325- and 2,325-3,720 m2) category was more positive because of a lack of supply in these segments (figure E).

Source: Adapted from a case study by Marvin F. Christensen, RREEF Funds, San Francisco, California, in Real Estate Market Analysis: A Case Study Approach (Washington, D.C.: ULI–the Urban Land Institute, 2001).

FIGURE D | Warehouse Construction Pipeline in the Valwood Submarket

FIGURE E | Projected Change in Warehouse Rents in the Valwood Submarket, 1999 to 2007

FIGURE F | Completions, Absorption, and Vacancy in the Valwood Submarket, 1990 to 2007

Selecting the correct site is crucial to the success of an industrial development, and it is important to ensure that as many criteria as possible are satisfied. Location directly influences a development’s marketability, the rate at which space can be absorbed during leasing, the rents that can be achieved, and the eventual exit strategy.

EVALUATING SPECIFIC LAND PARCELS. Because they lack the staying power necessary to survive the many unpredictable delays of the approval process, beginning developers should avoid buying land that is not ready for immediate development. Obtaining zoning changes or variances and conditional use permits, installing major off-site infrastructure improvements, or waiting for the completion of planned transportation improvements tends to require more time and capital than most beginning developers have.

It is especially important that water, gas, electricity, telephone, and sewer services with appropriate capacities be available at competitive rates in a site for industrial use. The site should be flat to accommodate the large pads that are needed for industrial buildings and should have a minimal amount of ledge rock, groundwater, or peat with soft ground.

The presence of oil wells, natural gas, contaminated soils, high water tables, or tanks, pipes, or similar facilities can cause major problems and should be carefully studied to determine present and potential dangers. When searching for sites for office and high-tech uses, developers should also consider the following criteria:

• distinctive terrain and vegetation, such as a water feature, that can help market the project;

• the standards of development in the surrounding area and the level of commitment among neighbors to maintain high standards;

• proximity to residential and commercial areas;

• proximity to recreational and cultural amenities;

• availability of shopping, hotels, restaurants, daycare facilities, and fitness centers;

• proximity to mass transit and availability of active transportation management associations and car-pools;

• proximity to educational and technical training facilities, such as universities, community colleges, or technical schools; and

• accessibility from freeways, arterials, or mass transit routes.

Despite the desirability of proximity to amenities such as shopping and recreation, industrial tenants who use trucks frequently prefer to be located in exclusively industrial areas rather than in mixed-use areas.

FINDING AND ACQUIRING THE SITE. Public agencies, such as local planning departments, redevelopment agencies, and economic development agencies, possess a considerable amount of information useful to developers in the search for potential sites. Most communities have comprehensive plans or master plans that indicate the areas favored for industrial development.

Real estate brokers specializing in industrial properties are another good source for information about potential sites. Developers should first narrow down their target area and then work with brokers familiar with it to obtain information on sites that may not currently be on the market.

Remaining sites in business parks that are approaching buildout should be considered as potential sites. Extra land around existing industrial buildings, often used for storage, may also present opportunities to expand a building for current tenants or to build another one. Owners of such properties may be interested in becoming a partner for the addition or may prefer to sell the land outright. If the land is in the back of the property, care must be taken with respect to access and visibility to ensure that the new building is leasable.

Infill sites offer developers the advantages of readily available streets, sewer, water, and other public services. But existing streets may be too narrow and space may be too constricted to allow for the creation of the high standards that tenants now expect of business parks. The developer should consult with local neighborhood groups and property managers of neighboring industrial and other properties to learn about potential problems in advance.

Site acquisition for industrial property follows the same four steps as for other forms of development: investigation before the offer is made, the offer, due diligence, and closing (see chapters 3 and 4).

During due diligence, developers should pay attention to hazardous wastes, especially if existing industrial uses are present nearby. Waste spilled locally may be spread by the water table to an otherwise clean site: a small amount of solvent or gasoline can show up as hazardous waste two or three years after it was spilled. Appropriately licensed engineers should perform water and soils tests; if necessary, developers should ensure that enough time is allowed to verify that no toxic waste is present by paying for an extension to the option. Sellers typically give buyers 60 days to perform due diligence for soils and toxic waste and 30 to 60 days for everything else.

Most developers face a standard dilemma during site acquisition. They need time to execute thorough due diligence, while the seller wants to close as quickly as possible. Both desires are perfectly reasonable, but protracted periods of time before closing are usually not met well by an eager seller and they can kill a deal. At the same time, rushing into a purchase to find out later that the site requires major environmental cleanup or going ahead without financing fully in place may be too high a price to pay to win the property.

As described in detail in chapter 3, site acquisition generally takes place in three stages: (1) a free-look period, (2) a period during which earnest money is forfeitable, and (3) closing. The agreed-on terms depend on market conditions. In a hot market, acquisition can be difficult for most developers and nearly impossible for those with financing contingencies.

Howard Schwimmer, executive vice president for Daum Commercial Real Estate Services, faced one of the hottest markets ever experienced in Commerce, California, but following a few basic tenets, he was able to successfully negotiate the purchase of a 240,000-square-foot (22,300 m2) industrial property that had fallen into foreclosure. Recognizing that complicated contracts and legalese in the first stage of an acquisition are usually not well received by a seller, Schwimmer submitted a letter of intent stating his ability to close the deal in three weeks with cash. A week or two after the seller accepted the first letter of intent, the parties agreed to a purchase and sale agreement that included an environmental review contingent on the transfer of the deed. The property was located on a parcel adjacent to contaminated ground, and lead had migrated onto the seller’s property. The lead was discovered during the environmental inspection; further testing and abatement extended the closing date by two months.

During this time, the buyer was able to conduct thorough due diligence and to leverage the project more favorably. The property was successfully acquired at a price considerably below the market rate.4

ENGINEERING FEASIBILITY. Preliminary engineering investigations are an integral part of due diligence. In the case of purchasing existing industrial buildings, engineering studies are among the first steps of feasibility analysis. A civil engineer usually leads the site investigation under the developer’s direction. Chapter 3 provides a comprehensive review of the site evaluation process for all types of development. For industrial development, the two most significant aspects of this process are utilities and environmental regulations.

Page Business Center in St. Louis is a three-building complex that combines new construction and renovation. Each building meets a different level of LEED certification.

GREEN STREET DEVELOPMENT GROUP, LLC

Utilities. Many manufacturing and some R&D facilities use enormous amounts of water and electricity. Because most water is discharged eventually into the sewer system, both water and sewage services are affected. The capacity to service such customers can be a good draw, especially in areas where the availability of water is limited.

A developer should meet with the local water company as early as possible to discuss plans and to learn about the utility company’s current capabilities and limitations. The developer’s engineer can obtain preliminary information on flow and pressure from the utility company. Fire departments usually require that the water system and fire hydrants be installed and activated before construction can start on individual buildings.

Some local agencies require the installation of lines to reclaim water for irrigation and some industrial purposes. Some localities require that two parallel systems, domestic and reclaimed, be installed on every lot. The developer should meet with the sewer company to determine the following information:

• capacity of sewage treatment facilities;

• capacity of sewer mains;

• whether gravity flow for sewage and drainage is sufficient or if pumps are necessary;

• the party responsible for paying for off-site sewer extension;

• the due dates for payments and impact fees;

• quality restrictions on sewage effluent: some sewage treatment plants impose severe restrictions on the type and quantity of chemicals that firms can discharge into the general sewage system;

• discharge capacity for sewage effluent;

• flow standards; and

• periodic service charges: although the rate structure for service charges does not directly affect the developer, it will influence prospective purchasers of property, especially heavy users, such as bottling plants.

Cities that use water consumption as the basis for sewer system service charges may penalize projects that consume a large quantity of water to irrigate landscaping. In such cases, the developer may attempt to negotiate treatment costs based on anticipated discharge rather than on water consumption.

Industrial land developers usually must front the costs for water and sewage lines and for treatment plants and then recover those costs as part of the sale price or rental income. They may also be reimbursed by developers of other subdivisions and owners of other properties that subsequently tie into the water and sewage mains. Most cities that provide for reimbursement by subsequent developers, however, do not permit the original developer to recover carrying costs. Moreover, because of the unpredictable timing of such reimbursements, developers cannot rely on them to help meet cash flow requirements.

For business parks with multiple buildings, developers should provide the local utility companies with information about the types and sizes of buildings in their plans so that they can project the estimated demand from the project. Electricity can be a big issue, especially for manufacturing and R&D users. The projected demand is used to design the local distribution system as well as the systems that will feed the local systems.

The frequency of power outages and gas curtailments during the winter should be investigated because this factor can deter potential tenants and buyers. Frequent outages also may influence the developer’s choice of target market or may change his decision to purchase the site altogether.

Environmental Regulations. Many federal environmental statutes can affect industrial development:

• The National Environmental Policy Act requires projects that use federal funds to produce an environmental impact statement for approval.

• The Clean Air Act requires the provision of information on anticipated traffic flow and indirect vehicle use.

• The Clean Water Act severely restricts discharge of any pollutant into navigable and certain nonnavigable waters.

• The Occupational Safety and Health Act requires employers to provide safe working conditions for employees.

• The National Flood Insurance Act limits development in flood-prone areas and requires developers who build in flood-prone areas to meet standards concerning height, slope, and interference with water flow. The act requires that a project not impede the water flow speed and volume that exist before development in any floodway traversed by the project.

• The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, also known as Superfund, addresses issues concerning toxic waste.

In addition, each state and local municipality may have its own environmental laws that affect industrial development.

Concerns about toxic waste, water supply, sewage treatment constraints, and sensitive environmental areas are forcing developers to perform very careful site investigation before closing on a tract. Although laws in most states give developers some recourse against prior owners in the chain of title for problems such as toxic waste, such protections are of little use if developers cannot proceed with their plans.

States continue to work to ease the liability put on developers when they engage in projects that come with environmental wildcards and potentially massive costs. This trend began in the 1990s in Massachusetts, when the attorney general’s office successfully negotiated a number of covenants not to sue with developers reclaiming brownfields. According to Raymond Bhumgara, the state recognized that future owners of sites should not be held liable for contamination that they did not cause.5 These covenants protect developers from being financially responsible for cleanups after taking ownership of a parcel and then having to pull out of the project. These types of covenants were more recently used in Atlanta, Georgia, in the development of Atlantic Station, a massive mixed-use project that was built on a site formerly occupied by a steel mill.

Urban adaptive use and the conversion of industrial properties to residential or live/work spaces generate new concerns for industrial developers. These conversions can have a positive effect on economic development in underperforming neighborhoods but can simultaneously cause incompatible uses in a single zone. Consequently, developers must create environmental impact reports to show, among other things, traffic and noise effects on adjacent properties. The gradual infiltration of residential uses into industrial zones is increasing the sensitivity of environmental requirements in these newly created mixed-use areas.

Once a site has been secured with a signed earnest money contract, the second, more detailed phase of the market analysis begins. The purpose at this stage is to investigate the immediate market area for information about rental rates, occupancy, new supply, and features of competing projects.

An important step before beginning this stage of market analysis is to define the property type or types most likely to be developed at the site to focus the research and determine which other properties constitute potential competition. This often overlooked step can help narrow the amount of research and reduce unnecessary effort.

INDUSTRIAL SUPPLY ANALYSIS. The first task in identifying future supply is to identify properties that are currently under development or construction. A drive through the submarket and follow-up calls to brokers and active developers can yield information on project sizes, completion dates, costs, and rents. Information on proposed projects that have not yet broken ground can be obtained from local planning and building departments.

Estimating the amount of additional space to the industrial supply beyond two or three years is difficult. Industrial buildings take a relatively short time to build, and when vacancy rates are low, the amount of construction can increase quickly. It is useful to look at factors such as the amount of land available for industrial development in the submarket and estimate the number of years before the available land supply is absorbed, given the likely pace of development. Some market analysts and data providers use econometric models to forecast new construction. Those numbers may not be entirely accurate, but they provide an approximation of future conditions.

Developers should keep in mind that the public sector may influence future supply. Cities and redevelopment agencies offer incentives to industrial tenants. If developers are not offered the same benefits as those available to others, they are at a competitive disadvantage.

An analysis of potential competitors helps assess the strengths of the proposed project compared with its competition. Again, a good place to start to collect this detailed data is from real estate brokers or management companies involved in the marketing of industrial developments who may be willing to provide plans or brochures and marketing materials on individual properties.

The developer should collect information on competing projects for the following items:

• overall site area and the size of individual lots and buildings if it is a multibuilding development;

• schedule, including date when marketing was initiated;

• occupancy levels at the date of the survey (acres sold, total square feet leased for each type of facility, percentage of space occupied);

• estimated annual land absorption;

• estimated annual space absorption by property type;

• initial and current sale prices and lease rates per square foot (land and buildings);

• lease terms and concessions;

• tenant allowances to finish interior space;

• building characteristics and the quality of architectural and landscape design, level of finish, quality of materials, signage, overall park appearance, and maintenance;

• development cost per acre;

• major highway access, rail availability, and utilities;

• amenities such as retail services, restaurants, open space, recreation, daycare, and health and conference facilities; and

• developer or current owner.

Demand models for industrial space often emulate office demand models, where a change in employment is a prime determinant of potential space absorption. However, industrial absorption often lags office demand. Multiplying the estimated number of new employees in a metropolitan area by the space allocated per employee provides an estimate of future space requirements. (It is important to keep in mind that space ratios are different for different types of industrial space.)

Analysts should also review other measures of metropolitan growth, such as gross metropolitan product or changes in total population or households. Growth in gross metropolitan product is a good indicator of absorption of warehouse or distribution space because it is a measure of the output of a local economy. Another indicator is manufacturing output as measured by the Federal Reserve Board’s Index of Manufacturing Output.6 Sometimes, demand is tied to growth in another nearby city. Warehouse space along the U.S. border in southern California is correlated with the growth of warehouse space in Mexican cities just south of the border.

After space demand is calculated for a metropolitan area, a final step is to estimate what share of the area’s absorption will be captured by the submarket where the property is located. Often, the concept of fair share is used. For example, if a submarket holds 8 percent of a metropolitan area’s industrial space inventory, then its fair share is 8 percent. Another method is to examine the historical share of net absorption in the submarket in relation to the metropolitan area’s net absorption over time. This information should provide an overview of how well the area stacks up against other locations. If a submarket is overbuilt, a developer may choose to sit on the land for months before beginning construction.

The Perris Ridge Commerce Center in Perris, California, is a 1.3 million-square-foot (121,000 m2) build-to-suit facility. When completed in 2009, it became the world’s largest LEED-certified warehouse.

RIDGE PROPERTY TRUST

Allan Kotin, of Los Angeles–based Allan D. Kotin & Associates, observes that market analysis for industrial space has more pitfalls than for other types of development. Industrial zoning is far more permissive with respect to land use than is commercial, office, or residential zoning. Industrial zoning often allows any of the other uses except, perhaps, residential and may therefore lead to overestimation of the size of the market. “There is a blurring of key distinctions in the general category that can lead to such errors,” notes Kotin. “Nominally industrial space that is half finished as office space and rents for about $1 per square foot [$10/m2] per month cannot be averaged with traditional industrial space that is 10 percent finished and rents for $0.45 per square foot [$4.85/m2].”7 Developers must look at the type of use and the degree of finish to determine rents accurately.

Industrial development provides a back door into both office and retail development, and market analysts sometimes mistakenly include absorption figures for office and retail users in their estimates of demand by industrial users. The distinction between product types can be made primarily by the amount of tenant improvements. Care must be taken to isolate the percentage of nonindustrial users. Office users in industrial buildings are often tempted to move back into higher-image office buildings, especially if office markets are soft.

Another concern is incubator industrial space, a frequently abused concept. Originally, incubator space was intended to house small firms that have the potential to grow into large ones. In practice, however, users are often marginal firms. Those firms in incubator space that actually grow and prosper are in the minority; thus, potential tenants should be carefully scrutinized. The different ways of measuring rents must be accounted for in the analysis. Some tenants have full-service leases, in which the landlord pays all expenses, while others have triple net (NNN) leases, in which the landlord pays no expenses. Some tenants have modified industrial gross leases in which the tenant pays direct utility costs, internal janitorial costs, and insurance, but the landlord pays for common area maintenance.

The approval process for industrial parks is similar to that described in chapter 3. Although the basic procedures for platting industrial subdivisions depend on the local area, most communities begin with some form of tentative approval, such as the tentative tract map in California. After appropriate review by the public, the developer is eligible to obtain a final tract map, also called the subdivision plat. The final tract map indicates the lot lines, setback requirements, allowable floor/area ratios (FARs), and other restrictions that determine the developer’s buildable site and its density.

The approval process for individual buildings may be as simple as obtaining a building permit or as complicated as the process for a full-scale business park. Normally, if the developer is building within the envelope of the existing zoning and subdivision restrictions, the approval process is similar to that for individual commercial and office buildings. If variances or changes in the zoning are sought, however, the approval process may be lengthy and expensive. Planning commissions and city councils tend to be especially concerned about truck traffic, as well as noise, fumes, and other negative effects of the planned development. Some communities are eager to attract the employment opportunities that industrial development generates, while many others are more concerned about keeping out truck traffic and preserving the character of business districts and residential neighborhoods.

ZONING. Several basic types of zoning districts are commonly used for industrial and business park development. Most common are the by-right districts, planned unit developments (PUDs) or floating districts, and special districts.

• By-right districts are the most traditional type of zoning district. Uses permitted by zoning regulations can be built by right without requiring further approvals.

• PUDs are known as floating districts because they can be applied anywhere the locality approves them. PUDs have flexible land use controls that can increase site coverage and provide for a mixture of uses. However, they usually require a long, drawn-out approval process.

• Special districts are approved by the local jurisdiction for a specific tract of land. The special district is then adopted as part of the local zoning ordinance. Provisions of the district are site specific and address issues such as land use, design, transportation, and landscaping.8

Zoning restrictions determine the size and placement of the structures that can be built on a given site. Typical zoning regulations for industrial buildings include

• front, side, and rear setbacks;

• height restrictions and FARs;

• access requirements;

• parking ratios;

• parking and loading design; and

• landscape requirements and screening regulations.

Most communities have maximum FARs for their industrial zones. In addition, landscape coverage ratios may be predetermined for the entire site or for the parking areas.

Although zoning ordinances have traditionally separated land uses from one another and limited the mix of uses in business parks, greater commingling of different land uses has occurred in recent years. The recognition that business parks often end up as sterile work settings without basic services or amenities for employees has led some communities to allow plans that include shopping facilities, restaurants, hotels, and even residential uses.

COVENANTS, CONDITIONS, AND RESTRICTIONS. Covenants, conditions, and restrictions (CC&Rs) are private land use controls and standards commonly used for business parks. CC&Rs take the form of a legally enforceable instrument filed with the plat or deed of individual buildings. They supplement municipal regulations, such as zoning and subdivision controls, and apply to virtually every aspect of a business park’s development, including site coverage, architectural design, building materials, parking requirements, signage, and landscaping.

Design guidelines can be included as part of the CC&Rs or as a separate document. They establish very specific uniform guidelines and criteria regarding bulk, height, types of materials, fenestration, and overall aesthetic design of the building. Subdivision restrictions sometimes require facilities for employees, such as outdoor lunch areas, recreation areas, and open space.

PUBLIC/PRIVATE NEGOTIATIONS. Increasingly, developers are required to negotiate agreements with local municipalities to secure approval for proposed projects. These agreements are especially helpful in volatile political climates in which pressures for no growth may cause city councils to change development entitlements unexpectedly. Public/private negotiations are also required when a developer seeks to work with a public agency on publicly owned land or in redevelopment areas.

In California, public/private contracts take the form of development agreements that usually take considerable time to negotiate.9 The agreements protect developers from later changes in zoning or other regulations that affect development entitlements and lend an air of certainty to the regulatory process by delineating most rights, requirements, and procedures in advance. Once adopted, no surprises related to approval should occur. Most agencies, however, require something in return, such as special amenities, fees, or exactions.

The use of public/private negotiations to shape the form of industrial developments is widespread, though not routine. In high-growth areas, public displeasure with the negative impacts of development has led to direct public involvement in negotiations with developers over specific projects. Many municipalities and counties have realized that well-planned industrial facilities such as business parks can provide significant revenues from property taxes. Some communities have therefore established redevelopment agencies to supervise negotiations with private developers and to represent the community’s interests as development proceeds.

The public sector’s role can include

• sharing risks with the developer through land price writedowns and participation in cash flows;

• creating utility districts and contributing toward offsite infrastructure;

• participating in loan commitments and mortgages;

• sharing operating and capital costs;

• reducing administrative red tape; and

• providing favorable tax treatment.

The role played by private developers is also expanding. Their functions may include paying for major off-site infrastructure and building freeway interchanges.

DEVELOPMENT AND IMPACT FEES. Some stages of the regulatory process require public hearings, and virtually all require some form of fee. The developer should understand the full range and scope of charges before closing on the land. Some of the more common fees that are assessed on industrial development projects include

• Approval and Variance Fees—Either a lump sum or a charge for the actual time spent by government personnel on processing an application;

• Plan Check Fees—Generally, a percentage of valuation;

• Building Permit Fees—Generally, a percentage of valuation;

• Water System Fees—Possibly based on amount of water used, meter size, frontage on waterlines, or a combination;

• Sewer System Fees—Usually based on expected discharge;

• Storm Drainage Fees—Usually based on runoff generated or on acreage;

• Transportation Fees—Based on trips generated or on square footage (some areas have freeway fees, county fees, and local transportation improvement fees);

• School Fees—Even industrial buildings are charged school fees per square foot in some areas;

• Fire and Police Fees—Usually based on square footage; and

• Library, Daycare, and Various Other Fees.

The types and amounts of fees vary drastically from one city to another. The developer must learn each city’s and each agency’s particular system of imposing fees. Because the fees can be imposed by a multitude of agencies, the developer should check with every agency that could possibly set fees. In many jurisdictions, the building department handles a majority of the fees and can be a good source of preliminary information.

STATE AND LOCAL INCENTIVES. State and local governments have developed a variety of incentive mechanisms to encourage industrial development:

• Publicly owned business incubator parks are designed to accommodate small startup companies; publicly owned research-oriented parks cater to high-tech companies.

• Enterprise zones, created by many states to encourage new industry in economically depressed urban areas, offer incentives to companies that locate in the zones. These incentives include various combinations of property tax abatements, industrial development bonds, exemptions from income and sales taxes, low-interest venture capital, infrastructure improvements, and special public services.

• State and local grants offer revolving commercial loans, loan and development bond guarantees, infrastructure projects that aid particular industries, and even venture capital funds.

• Tax increment financing is useful in areas with low tax bases. The difference between new taxes generated by development and the original taxes is reserved for infrastructure improvements for the designated area. Redevelopment agencies frequently use tax increment financing as a source of revenue for their projects.

Main entrance, Franke Corporate Headquarters in Smyrna, Tennessee.

© 2009 JIM ROOF CREATIVE, INC.

Industrial development bonds were very popular in the late 1970s and early 1980s, but the 1986 Tax Reform Act severely restricted the types of projects that could qualify for tax-exempt financing. Originally intended to bring manufacturing to depressed areas, bonds were used instead to provide tax-exempt financing for a number of activities, in both industrial and commercial development. Some communities abused industrial development bonds by using them to finance activities such as fast-food restaurants and other businesses in areas in which conventionally financed development was already occurring. Businesses complained that the bonds gave certain firms an unfair cost advantage and questioned the contention that industrial development bonds actually stimulated much development that would not otherwise have occurred. Despite these problems, a number of cities have used industrial development bonds effectively to generate development in once-stagnant areas.

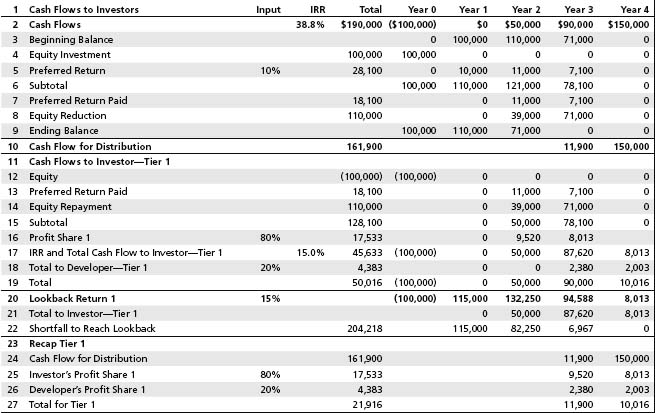

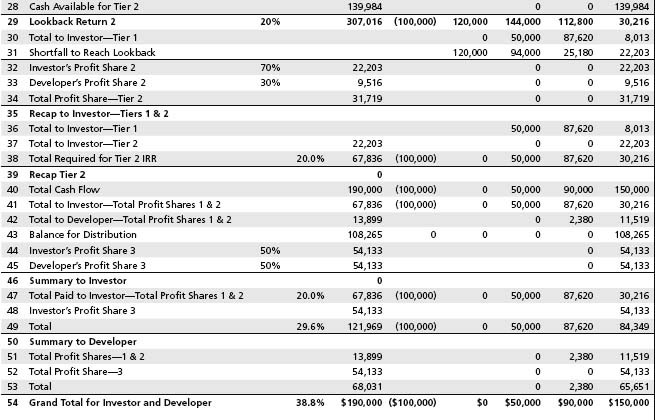

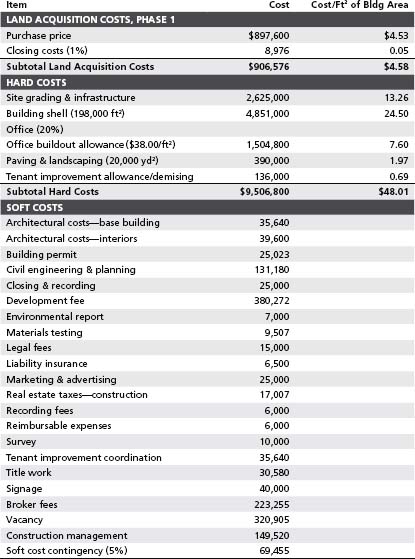

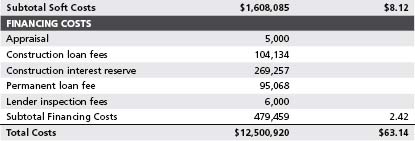

As with other product types, financial analysis for industrial development is performed several times during the feasibility period. At the very least, it should be updated three times before closing on the land: (1) before submitting the earnest money contract, (2) before approaching lenders, and (3) before going hard on the land purchase.

At each stage of development, more information is known with greater certainty and accuracy. Data from the market study, design data, and cost estimates are incorporated into the financial pro forma as the information becomes available. Developers should not wait until these studies are done, however, before performing financial analysis; cruder information based on secondary sources may be used at earlier stages. For example, as soon as the size of the building to be built is estimated, the construction cost can be estimated from average costs per square foot for similar projects. Contractors and other developers will usually share this cost information.

The method of analysis for business park development is different from that for industrial building development:

• Business park development is a form of land development and follows the approach for analyzing for-sale property described in chapter 3.

• The stages of analysis for industrial building development are similar to the five stages of discounted cash flow (DCF) analysis for income-producing property described in chapter 4.

Hints for Dealing with Regulatory Agencies

Industrial developers offer some advice for dealing with agencies during the regulatory process:

• Industrially zoned areas have the fewest restrictions of all development types, but many areas prohibit certain industrial uses.

• Check the city’s general plan to make sure that the property is intended for industrial uses. Problems are more likely to occur if developers want to change zoning.

• Subdividing a lot and selling it as raw land or with buildings requires a platting process that will take at least six months.

• Be sensitive to all community activity that may lead a city to restrict or delay development by means of emergency ordinances such as water moratoriums.

Sources: Donald S. Grant, the O’Donnell Group; and Timothy L. Strader, Starpointe Ventures.

For building development, the major decision tool is the DCF analysis, a five- to ten-year pro forma showing the property’s operations from the completion of construction to sale. It incorporates rental rates, rent concessions, lease-up time, and expected bumps in rents over the holding period.

Internal rates of return are computed on the before-and after-tax cash flows. Industrial developers like to see IRRs on total project cost of 13 to 15 percent for an all-equity (unleveraged) case in which zero mortgage is assumed. A 15 percent unleveraged IRR typically produces a leveraged IRR (with a 70 to 75 percent LTV ratio) on equity in the high 20s. Leveraged IRRs on equity need to be 20 to 30 percent to entice investors.

The developer should use the financial pro forma to perform sensitivity analysis to test the impact of various assumptions on the results:

• For industrial building development, what effect do leasing schedules have on the IRR?

• How sensitive is the IRR to changes in assumptions with respect to rental rates and concessions, construction costs, financing costs, interest rates, release assumptions, and inflation assumptions?

• For industrial park development, what effect does lowering land prices to sell the land faster have on the IRR?

• What is the effect on the IRR if more money is spent up front on such items as amenities, roads, utilities, and entrances to permit faster sales or higher prices?

Because in-depth examples of multiperiod cash flow analyses for both land development and building development are included in chapters 3 and 4, none are included here.

This section deals first with design considerations for business parks and second with building design for the major industrial building types.

Site design is the biggest unknown variable in the design and construction of industrial building projects. Therefore, it carries with it the most risk. Jay Puckhaber of Panattoni, a large industrial developer, notes that “the science of industrial building design has reduced the structure to a highly refined assembly with few variables; this is why across the world, the buildings are so similar. On the other hand, sites are highly variable from location to location. Soil, site hydrology, and other local conditions can greatly affect the suitability of a property for an industrial project, and therefore a good local civil engineer who understands the local conditions is an important member of the project team.”

Industrial building projects require large tracts of flat land as a precondition. They are unable to adapt to significant topographical changes that a residential or office project might.

Site design for a business park must also consider a variety of interrelated variables, from lot layout to street systems to landscaping plans. Flexibility is a key issue. The site plan should easily accommodate new buildings, changes in traffic flow, and division into smaller parcels.

The planning process generally follows three general stages: concept planning, preliminary planning, and final planning. Each stage involves the collection and analysis of information about the site and the identification and evaluation of alternatives. Throughout the entire process, the developer and project planning team should maintain a meaningful dialogue with relevant public agency representatives because they can assist in compliance and in facilitating public support.

PLATTING AND LOT SIZE. Lots 200 to 300 feet (60–90 m) deep are popular for a variety of industrial uses. Large single users may require deeper lots of 500 feet (150 m), which can be subdivided if necessary. Lot width is variable and depends on the needs of the user. If parking requirements are minimal, building coverage may range from 50 to 70 percent of the total lot area. For example, a 20,000-square-foot (1,860 m2) building in an area limited to 50 percent coverage would occupy a 40,000-square-foot (3,720 m2) site. If the remaining 20,000 square feet (1,860 m2) were all used for parking, at 350 square feet (32.5 m2) per parking space on average, then approximately 57 spaces would be possible, for a parking ratio of 2.9 spaces per 1,000 square feet (95 m2).10

PARKING. The amount of parking required for individual buildings in a business park is dictated by zoning requirements and users’ needs, although frequently these two requirements differ. Most jurisdictions’ zoning and building codes require a minimum number of parking spaces based on the square footage of different uses being built, expressed as a ratio of spaces to 1,000 square feet (95 m2) of leasable space. Ratios have been increasing in recent years, and they now range from one to two spaces per 1,000 square feet (95 m2) for warehouse uses to three, four, or more spaces for R&D flex buildings and other predominantly office uses.

STREET DESIGN AND TRAFFIC. The location of external roads provides the basis for internal street systems in business parks. The ideal street layout for a business park provides easy access to the nearest major highway or freeway and discourages unrelated traffic. A public highway that runs through the middle of a park reduces the developer’s expenditure on internal roads and enhances the value of frontage sites, but it also tends to divide rather than unify the development, to bring heavy unrelated traffic through the middle of the park, and to increase the possibilities of accidents.

The more points of ingress and egress in a development, the better. For instance, assume that a 160-acre (65 ha) business park is being developed with an employment density of 20 persons per acre (50/ha). With 3,200 employees at 1.1 per car, approximately 2,900 cars would be in circulation. Three planned access points could probably accommodate that volume in just over an hour. If, however, a half-hour traffic jam occurs at the park nightly and the competing industrial park down the road does not have a traffic jam, the owner of the first park faces a serious marketing problem.

Within the site, roads must be designed to permit maximum flexibility in shaping development parcels because changes in demand could require modifications in site design at some point in the future. Contemporary business parks are most often designed using simple grids common to earlier parks while also taking into consideration topographical and site-constraining conditions.

Because traffic is a chief concern of most communities, developers should understand the impact that their proposed developments will have on traffic. One lane of pavement typically handles 800 to 1,200 trips per hour, depending on the street layout and traffic control at intersections. For purposes of design, developers should estimate the percentage and directional distribution of truck traffic. Overdesigning the traffic system is better than underdesigning it, as the intensity of future uses is unknown.

Design considerations also include road thickness, pavement type (concrete or asphalt), road curvatures, and sight distances for stopping, passing, and corners. Standard drawings of the following items are available in most agencies:

• typical street sections;

• commercial entrances and private driveways;

• culs-de-sac and turnarounds;

• intersections, interchanges, and medians;

• guardrails, bridges, and bridge approaches;

• signalization, signage, and lighting;

• drainage, curbs, and gutters;

• erosion control features;

• sidewalks, paved approaches, and pavement joints;

• safety features; and

• earthwork grading.

Standards are subject to constant revision. The developer usually relies on the civil engineer to ensure that street and utility designs conform to the latest standards.

Culs-de-sac need a paved turnaround of 100 feet (30 m) in diameter to allow trucks with 45-foot (13.7 m) trailers to turn around without backing up. Roadway widths depend on the amount of traffic the roadways handle, median design, and the absence or presence of parking. Some designers prefer that the major roads leading into a project have no parking and that interior access roads allow limited parking. Street parking can be advantageous to some businesses because it can provide space for overflow visitor parking.

WALKS AND LANDSCAPING. A carefully designed pedestrian system can be an attractive selling feature, particularly if it is connected to a nearby retail or recreation area. If the business park includes significant open space, then a pathway system (perhaps including a jogging path) through the space, away from heavy traffic, is also an attractive amenity.

In designing aesthetic features such as berms and slopes, developers should be aware that mowing equipment cannot handle slopes steeper than three to one (three feet horizontal to one foot vertical). Care must also be taken to avoid interfering with drivers’ visibility by landscaping and berms at road intersections. Where industrial uses adjoin residential uses, deep lots, berms, fences, landscaping, or open space can help to create a buffer.

TRUCK AND RAIL ACCESS. Well-designed truck access, docks, and doors are critical to the operation of most industrial facilities. The distance of the truck apron from the truck dock affects the on-site maneuverability of trucks. The current maximum length for a tractor and semitrailer can be somewhat longer than 70 feet (21.3 m). Therefore, the current recommended standard for a truck apron is 135 feet (41.1 m) minimum from the truck dock; some developers provide as much as 150 feet (45.7 m).

Project Landscaping Checklist

The following basic criteria must be considered when designing the landscape for a business park:

1. STREETSCAPE—Whether dealing with one parcel or a multitenant park, the objective is for the project to look good from the street, for the street to look good from the project, and for the street to serve pedestrians as well as vehicular traffic. Design elements include berming, pedestrian paths, sidewalks, and trails.

2. ENTRY LANDSCAPE—Monumental signage clearly marks and identifies a business park site. For an individual parcel, a site sign might be included in addition to exterior building signs. Standards set for the park dictate the type and placement of signs.

3. CIRCULATION—Site circulation, whether vehicular or pedestrian, should be direct and clearly marked. Way-finding devices include signage, berming, tree planting, seasonal planting, site furnishings, and artwork.

4. FRONT DOOR—Landscape architecture can reinforce the significance of a main entrance through paving materials and patterns, plantings, fountains, and plazas. Each choice comes with a cost; when projects are subjected to cutbacks, the last thing to go is usually the identity at the front door.

5. SERVICE AREAS—Service areas include truck docks, loading areas, Dumpsters, recycling areas, and outdoor mechanical, electrical, and communications equipment. When building orientation does not permit complete screening, other methods can be employed, such as commercial and evergreen fences, walls, and berming. Certain plant materials work better for this type of screening, and the landscape architect can recommend what is most appropriate for the site.

6. STORMWATER MANAGEMENT—Local codes contain requirements for stormwater management that typically state water must be retained on site for a period of time before it can be released. various retention methods can be used, from wet ponds to dry ponds to underground storage. The site’s size, topography, and budget help determine which is the most practical and cost-effective choice.