Art: Siobhan McDonald

Abby (I.)

A human being is not like a bullet. We don’t begin with a single act—a finger on a trigger. Our existence depends on the confluence of choice, desire, factors far more complex than angle, range, wind. Even if, in hindsight, our outcome seems inevitable, the trajectory of a life is not so easily calculated.

So, how to avoid an undesired outcome? Where do you start? Not at the end. You have to go back. You have to unravel. But how far? To the bottom of the stairs, the beginning of the breakdown? Further. Before he buys the gun, before he becomes addicted, before the marriage dissolves, before the army. Before the child. Before the first confluence is even crossed. You have to go back to where the lines are clean.

Back to when life was simple.

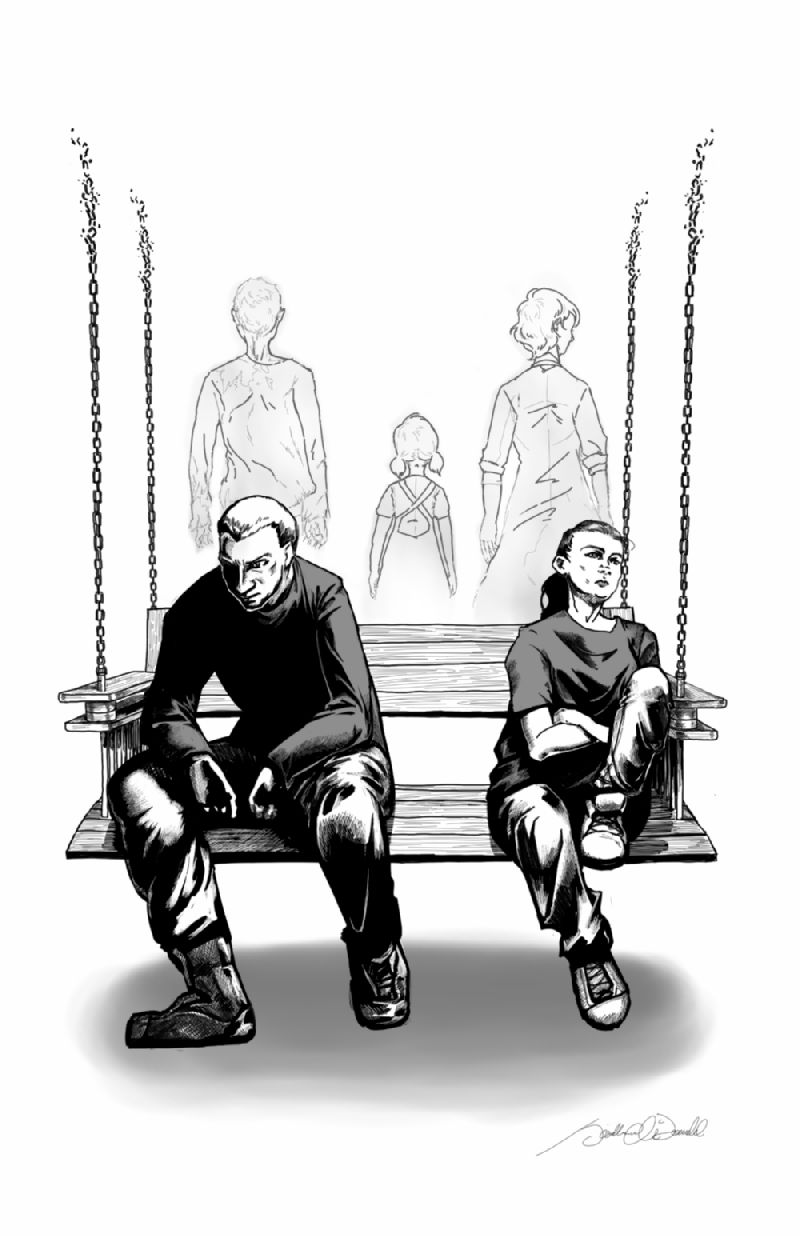

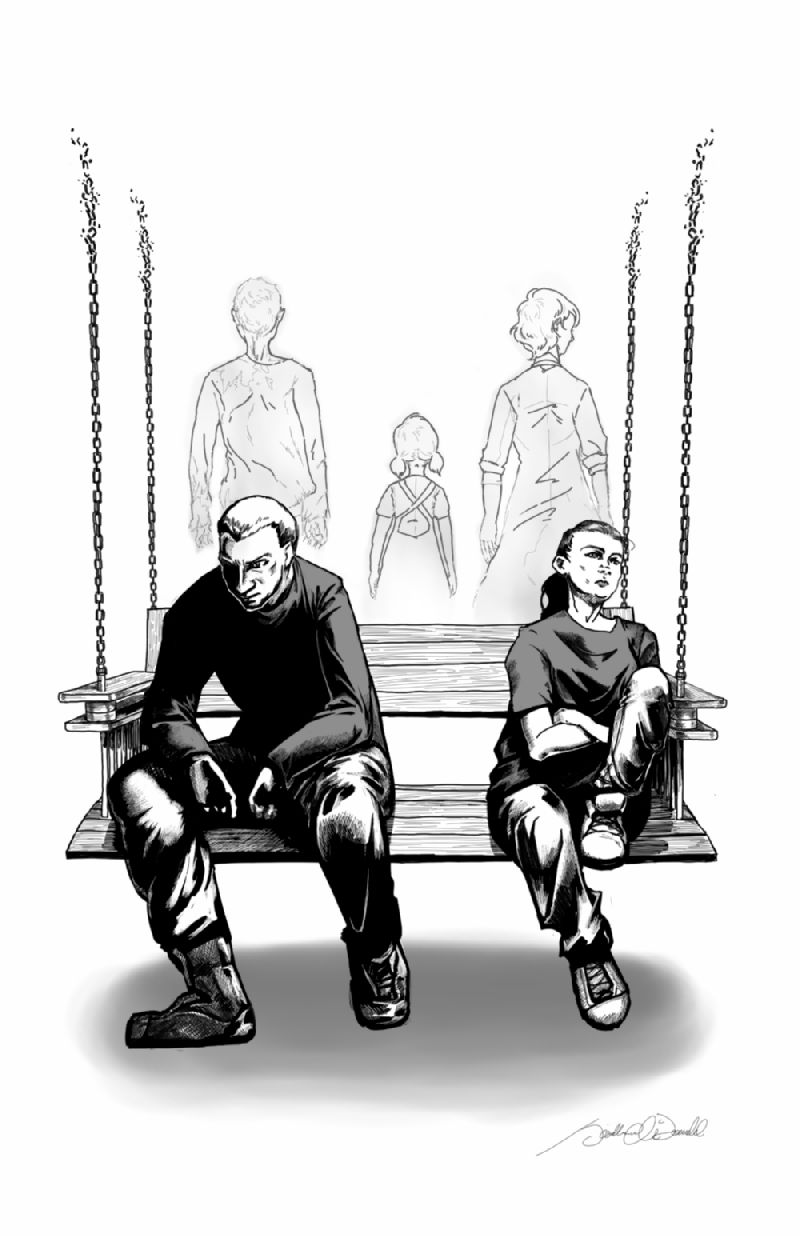

Jesse

While his mother had her hands stuck inside the turkey, Jesse slipped outside to spark a joint.

The neighborhood was quiet, full of fireplace scents and white chimney smoke. Clearing a thin layer of snow off the backyard swing, Jesse settled on the bench and rocked, enjoying the familiar, rhythmic squeak of the chain.

Then Abigail came around the corner of the house, red sneakers crunching over snow. Thirteen years old now, she seemed to have aged years instead of months since Jesse went away to college. Black New Moon t-shirt but no coat, blonde hair dyed black and swept up in a severe ponytail. She stopped when she saw him and put a hand on her hip. “What are you smoking?”

“I’m not.”

Abby looked at him with that odd, fierce gaze that had been unnerving him all week. “That’s weed. Give me some.”

Jesse coughed into his glove. “I’m not giving weed to my baby sis—”

“I’ll tell Mom you have it. M-oooom!”

“Shut up! Fine! Jesus.”

Jesse felt a qualm as he handed her the joint. He could still picture Abby dancing in pink footie pajamas, brandishing her first lost tooth. “Just take a little. A puff. Not too much.”

Blue eyes twinkling, Abby pinched the roach between black sparkly fingernails and sucked it like a straw.

Jesse gaped. “How long have you been smoking?”

“Oh,” she said, and held her breath. Exhale. Handed it back to him. “A while.”

“Jesus.” Jesse took another hit. When he went to pass it back, Abby shook her head.

“I don’t have much tolerance in this b—…” She smiled goofily and shook her head. “Mm. Hey. Do you have any cigarettes?”

Jesse pulled the packet of Reds from his coat and handed her one. The lesser of two evils, he figured. Abby smoked the cigarette like a death-row inmate, head thrown back. When she coughed, she giggled, which made Jesse giggle.

Abby brushed off a patch of snow and sat next to him on the swing. “I want to ask you a question,” she said. “It’s… for a story I’m writing.”

“Okay.”

She stared at the house as if searching for words in the grooves of the aluminum siding. A sudden breeze blew snow from the roof, a starburst of particles and light.

“Say you had a kid.”

“Oh…kay?”

“And… say you found out you were going to die. But. Say someone could make it so that you didn’t. Have to die. Maybe.”

“What, like… they found a cure?”

“No. I mean… well. I just mean what if someone could fix things? Fix… your life.”

“Abs, I don’t know what the hell you’re talking about.”

“I’m talking about second chances, Jess.”

Jesse shrugged. “Whatever. Sounds great.”

“But…” Abby took a deep breath. “If someone could give you another chance, to do things differently… so that maybe bad things wouldn’t happen… it might mean she wouldn’t ever be born.”

“She who?”

Jesse caught a flash of Abby’s eyes, and then she was examining her nails on either side of the still-burning cigarette. “Your daughter.” She put her nail in her mouth and chewed it off. Spat, took a drag from the cigarette. Looked at him. “Would you do it?”

Jess laughed. “I’m confused.”

“Damn it, listen. If you could live your life differently so that you might not die, but it meant your daughter might not be born, would you do it?”

“I don’t know. No.”

“No?”

“Nah.”

“Why not?”

“I don’t know. What do you want me to say? I’m not a father.”

“But if you were.”

“But I’m not. And people don’t get do-overs. This is stupid.”

“But say you could.”

“How?”

“It doesn’t matter.”

“What. A time machine? Aliens? A magical doorway?” He was teasing, but Abby wasn’t smiling.

“Damn it, Jesse, how is not the point.”

“Is there something about my future that I should know?”

The cigarette was burning to ash between Abby’s fingers. Jesse took it from her, smoked it down to the filter, and crushed it out.

“If I had a kid,” he continued, “… even if I could make it so they never existed, somewhere they would have existed. Right? On some… level? Or whatever? Well… you know what Mom always says. Once you have a kid, your life isn’t just yours anymore.”

He’d been looking at the side of the house. When he looked back, Abby was staring at him. It was getting creepy. “What?”

“So…” Abby whispered. “No?”

Jesse shrugged. “It just wouldn’t be right. Right?”

Abby’s eyes filled with tears, sparkling like snow-dust before cascading down her cheeks. In the next moment, she was hugging him. Jesse’s hands went awkwardly to her back. He hadn’t held her since she was small enough to carry.

“Hey, it… s’ok. What’s wrong?”

“I’m sorry, Jesse, I’m not a genius. I kind of figured you’d say that. But I hoped... I don’t know. I love you.”

“I… love you, too?”

Abby disentangled herself and swiped at her runny nose. “I gotta go.”

“Okay.”

She jumped off the swing and looked at him. She looked way older than she should.

Then, for just a moment, Jesse saw Abby standing on a ridge over a forested valley. She wore hiking gear and a cowgirl hat over short blonde hair, and that was weird. He’d never been hiking with Abby.

The wind kicked up, stronger this time. Abby bristled, her ponytail (black, not blonde) striving to break free from her head.

“It’ll pass,” she said. “It’s just the distortion.”

“What?”

“You won’t remember this part, anyway, but Jess... I only had a few minutes. I didn’t know what else to do.” She looked like she was about to start crying again, but she turned away.

Jesse watched her crunch back to the house. He felt dizzy and sick, like he used to get from reading comic books on long car trips. His head was full of Abby images—Abby in her car seat, sleeping slack-jawed and drooling. Abby in a cap and gown. Abby a grown woman on a mountain top, on a rooftop, in a white room. Abby yelling, crying, staring down at him while the world spiraled, shuttered, faded.

And his own voice, saying things he’d never said.

You’re the genius, Abby. All those degrees. Maybe you can figure out how to fix me.

Jesse turned and spat a bad taste from his mouth into the husks of his mother’s tiger lilies. The weed was probably laced with something. Fuck.

He hoped Abby would be all right.

He dropped his coat in the hall so Mom wouldn’t smell it on him. He should have said something to Abby, too, told her to put on some perfume or something, but when he walked into the kitchen she was there with Mom already. The two of them stood at the counter in matching aprons, smothered in the aroma of roasting turkey and diced onions. They glanced at him before turning back to their work, twin gestures of feminine dismissal.

Jesse plucked a carrot stick from the vegetable platter and bit it in half. “So what’s your story about, Abs?”

“What story?”

“The one you’re writing.”

Abby scooped a handful of cut celery into the big metal bowl. “Well, I’m thinking about this one about a girl who can change into either a vampire or a werewolf, at, like, will? ‘Cuz her parents were one of each. And she falls in love with this guy who’s a prince from this rival cadre, but she doesn’t know it. But I haven’t started writing it yet.”

“What about the time-travel thing?”

Abby scowled at him. “I don’t write time-travel. Sci-fi is stupid.”

“What about the thing with the dying, and the kid…?”

Jesse trailed off. He felt nauseous again, like what happened outside, but more of an aftershock than a wave—and with it, another déja vu ‒ like memory of something he’d never done. Handing Abby a bundle, tight and warm. It smelled of hospital sheets and powder, and it was somehow the most important thing in the world.

Sierra. For the mountains. And Elizabeth. For Mom.

“Jesse, what are you talking about?” Another clump of celery went into the bowl. “God. You’re so weird.”

Jesse put the remaining half of the carrot back on the plate. His appetite was gone.

Abby(II.)

Maybe you can figure out how to fix me.

Dr. Abigail Walker rode the shuttle straight from the hospital to her offices at Phalynx Corp. Her com buzzed in her pocket, unanswered. At home, Abby’s partner, Michael, would have just learned of Jesse’s death.

She inhaled a cigarette as she jogged between the platform and the security terminal. Pausing to deposit the stub in a vacuum slot, Abby caught a glimpse of herself in the vid-feed. Red-eyed, haggard. She’d been keeping a vigil for weeks, fussing over the tubes and monitors, the bioplastic cap sewn over the missing parts of Jesse’s brain and skull. All for nothing—she couldn’t save him. He’d told her that, his eyes fixed over her shoulder, indifferent, his body a shrug with every induced breath. In the end, the machines cried out for him, the nurses swarmed like pink vultures on his blanketed bones, but it was too late. Her brother was gone long before he became a corpse. He was gone even before he put the gun to his head, that day on the roof of the rehab clinic.

Where did it start? How far back?

All down the long white corridor to her suite, Abby rewound history in her head, looking for a way in. When, she wondered. Not if—she was reasonably sure she could do it, even if it meant subverting the goodwill of her employer. She’d been playing with the idea for years, even went so far as to submit a research proposal. It’d been tabled for ethical concerns—the long-term effects of temporal displacement on cellular evolution had yet to be determined. But Abby had the resources. She had a treasure-trove of data in her lab and a strand of her own thirteen-year-old hair. (She’d tossed the New Moon t-shirt in a box just after the Thanksgiving that Jesse announced he was dropping out of college. For whatever reason Mom had saved it, airtight in a bin in the attic, unwittingly preserving that precious bit of DNA).

Abby swiped her ID card, entered her office, and brought her terminal to life. A photo at her work station caught her eye—Jesse and their mother at the military hospital in Sacramento, where Sierra was born.

Even then, holding his infant daughter, Jesse hadn’t been all right. Too thin. A certain look in his eyes. Or was that only hindsight?

On the day of his suicide, Jesse had laughed at her. You’re the genius, Abby, he’d said. All those degrees. Maybe you can figure out how to fix me.

And maybe she could. She could go back. As to whether or not she should… she’d figure that out when she got there.

The family photograph zeroed out. Grabbing a data key and her ID, Abby headed for the lab.

Sierra

The little girl had been making birds. Graceful, sweeping shapes that disappeared back into gravy almost as fast as she could carve them with her spoon.

The other children ate their dinners, happy, crammed in around Mama Lucy’s glass coffee table. There were cartoons on the big screen. Later, everyone would get a slice of pumpkin pie.

The little girl didn’t care about pie. Also she didn’t like this cartoon, or this house, and Mama Lucy was not her mama. Her mama went to sleep with a needle in her arm and never woke up.

There was a knock at the door and Mama Lucy swished through the family room to answer it. The girl could see the front hall from where she was sitting. She recognized Miss Millie, the lady who had taken her from her house and brought her here. Miss Millie saw her looking and smiled. Mama Lucy smiled too, the way she only did when other grownups came over.

The third lady did not smile. She was tall and blonde, with a face the little girl thought she should know but couldn’t think why. Then she realized it was not unlike her own. The little girl felt her heart begin to flutter like birds’ wings inside her chest.

“Hi, sweetie.” Miss Millie came over to the coffee table. She put her hands on her knees and bent closer, her voice quiet, though everyone in the room was listening. The other kids kept their eyes on the cartoons, forks going up and down into mouths. They were watching with their ears.

“Could you come into the sitting room for just a little bit? You’ll be back in time for dessert,” she added, as if this mattered. The little girl was already leaving her spoon in the gummy mashed potatoes and rising to her feet.

They led her into the tiny room off the front hall where Miss Lucy kept the dressy dolls no one was allowed to touch. They sat her on the checkered sofa. The blonde lady sat on the chair. Miss Millie and Mama Lucy went into the kitchen for tea.

The lady smelled like cigarettes. Her fingers twitched like she needed one real bad, like the little girl’s mother’s used to do. “I’m Abigail,” she said.

“I’m Sierra. Sierra Elizabeth.”

“Yes, I know. I’m your aunt.”

Sierra was about to say that couldn’t be right—her mother didn’t have any brothers or sisters. Then she closed her mouth, not wanting to seem stupid. She’d had a father, once, too.

“Do you remember your dad?”

Sierra shook her head. “Miss Lucy says he died, too.”

“Yes.” After a while she added, “Sierra…. That’s the reason I’m here. I’m your closest relative now. If you want… you can come live with me.”

Sierra picked up one of the dolls from the basket on the floor and began to tug its auburn hair.

“When did my dad die?”

“Friday.”

Friday? “Why didn’t he come before?” Sierra asked, trying hard to sound like she didn’t really care about the answer. She’d been living with Mama Lucy for seven months.

“He would have if he could. He was sick.”

“My mom said he was a loser junkie.”

The lady—Abigail—could have said the same thing about Sierra’s mom. It would have been true. But she didn’t. Sierra appreciated that.

“It’s pretty much the same thing, isn’t it?”

“Why didn’t you come, then?”

Abigail shifted on the sofa and didn’t answer right away. She looked like she half didn’t want to be there.

Sierra studied her over the doll’s head. “You don’t like kids.”

“I’m ambivalent about them, to be honest with you.” Abigail laughed at herself, obviously thinking Sierra didn’t know that word. But Sierra understood a lot of things. Like that this “aunt” wasn’t here for Sierra so much as she was looking to do something nice for someone else. Sierra’s dead dad, maybe, or the grandmother she was supposed to be named for.

“But it’s not that,” Abigail continued. “I was hoping things would turn out different. But here we are.” She offered a sad smile. “You look like my mom.”

“I look like you.”

“Yeah, I think you do. They say you’re very smart. And artistic. You draw?”

Sierra nodded. “I write stories.”

“I used to write too,” said Abigail. “A long time ago. I was never good at finishing, though.”

“What do you do now?”

“I’m a biophysical engineer. That’s a kind of doctor. I design programs that trace back cellular evolution.”

“Why?”

“To reverse degeneration… disease.”

Sierra thought of her parents. “So you fix people?”

“In theory.” Abigail studied her hands in her lap. “Not everything can be fixed.”

“At least not by going backwards.”

Abigail stared at Sierra. “Right,” she said. “Anyway. I work a lot. I don’t know anything about raising kids. But I have a nice apartment, and my boyfriend can cook, so. It’s up to you, Sierra. What do you think?”

The girl made a pretense of considering it, then dropped Mama Lucy’s doll into the basket, head first. “Can we go now?”

Abby (III.)

We do not begin with a single act, Abby thought, struggling to keep her grip on the handhold as the shuttle swayed over downtown, but perhaps we can be defined by one.

Lizzie, straddling the middle aisle with all the strength and grace of youth, glanced up from her com and gifted Abby a smile. She was in the midst of her midterm exams at University, necessitating constant earnest conferences with her classmates, but she knew the ride was rough on Abby’s arthritic joints.

“Sure I can’t beg you a seat, Mom?” she asked, tilting a head towards the benches.

“I’m fine,” Abby lied, banishing any hint of pain from her face. Lizzie turned back to the device in her hands, immersing herself once more in the depths of xenolinguistics.

Abby studied the top of the young woman’s honey-blonde head, seeing not the tall, confident Lizzie as she was now, but Sierra Elizabeth as she had been, small and strange on that first ride home so many years ago. Sierra with her face pressed up against the window to see the city sprawled hundreds of feet below, the magnificent convergence of lights and steel, the hugeness of a world where she had lost and gained a family in a single night. Beneath the ache in her hand, Abby could still feel the avian frailness of the girl’s shoulder as she reached out to hold her, moved by some fetal sense of love.

Was that it? Was that the moment she’d become not-Abby, but a parent? Or had that happened earlier, with the knock on the door at the foster home? When the word “adoption” first left her lips? The night that Jesse died and Abby ripped herself in and out of time, the moment she returned, shaking and vomiting, to her laboratory floor?

Or had it been in motion all along?

“Our stop is next,” Lizzie said, taking Abby’s hand. “I’m so glad we’re doing this. I’m starving. Let’s share a plate of tikka masala, what do you think?”

“Absolutely,” said Abby, though she had little appetite anymore. The aging process was catching up with her—hardly noticeable for the first few years since her trip back, but now she was dyeing her hair, taking pain meds, treating her skin—it was getting harder to keep Lizzie and Michael from realizing the extent of her degeneration.

To tell Lizzie she was growing old quickly, irreversibly, Abby would also have to explain why. She wasn’t ready for that conversation. She knew she’d have to do it, sooner rather than later. But not now. Today was about Lizzie—a special mother-daughter lunch at their favorite restaurant to celebrate the nearness of a bright and promising future. That was how it should be.

The past could come later.

Shannon Connor Winward is an American author of speculative fiction and poetry. Her writing appears in Fantasy & Science Fiction, Analog, Persistent Visions, Pseudopod, and elsewhere. Shannon is also an officer for the Science Fiction Poetry Association, a poetry editor for Devilfish Review, and founding editor of Riddled with Arrows Literary Journal. She lives and writes in Newark, Delaware.