There was once a fairy, a sweet little fairy who lived in a freshwater spring, not far from a village. You know, don’t you, that in the old days, the land of Gaul was not Christian, and that our ancestors the Gauls used to worship fairies. In those times, the villagers worshipped this little fairy. They decorated her spring with flowers, brought her cakes and fruit and, on holy days, they even put on their finest clothes and there went to dance for her.

Then, one day, Gaul became a Christian land and the vicar banned the local people from bringing offerings and going to dance around the spring. He claimed that they would lose their souls and that the fairy was a demon. The villagers were quite sure this wasn’t true; still, they didn’t dare contradict the vicar, because they were afraid of him. But the oldest villagers continued to go in secret and leave their gifts beside the spring. When the vicar realized this, he was very cross. He had a great stone crucifix set up beside the spring, then he organized a procession and pronounced a whole string of magic words over the spring, in Latin, in order to drive the fairy away. And the people really believed he had managed to chase her away, for no more was heard of her for the next 1,500 years. The older people who had worshipped her died; little by little, the young people forgot about her, and their grandchildren never even knew that she had existed. Even the vicars, her sworn enemies, stopped believing in her.

Yet, the fairy had not abandoned her spring. She was still there, deep in the spring, but she was hiding, for the crucifix stopped her from coming out. Besides, she had understood that nobody cared about her any longer.

“Patience!” she advised herself. “Our time is past, but the Christians’ time will also pass. One day, that crucifix will crumble away, and I shall be free once more…”

One day, two men came walking up by the spring. They were engineers. They noticed that the water was plentiful and clear, and decided to use it to supply fresh water to the nearby town.

A few weeks later, the labourers arrived. They pulled down the crucifix, which was in their way, then they enclosed the spring and channelled its water in pipes, all the way to the town.

This is how, one fine day, the fairy discovered she was living in a network of pipes, whose twists and turns she began to follow blindly for miles, wondering all the while what on earth had happened to her spring. The farther she went, the narrower the pipes became, branching off into even more, secondary pipes. The fairy turned and turned again, now to the left, now to the right, and in the end she popped out of a great copper tap, over a big sink made of stone.

She was lucky, really, for she could just as easily have come out in a toilet cistern, and then, instead of being the fairy in the tap, she would have become the fairy in the toilet. Thank goodness that didn’t happen.

The tap and the sink were part of a kitchen, and the kitchen happened to be part of a house where a family of working people lived: a father, a mother and their two teenage daughters. It was some time before they saw the fairy, for fairies do not come out during the day, only after midnight. It so happened that the father was a hard worker, so was the mother, and the two daughters went to school, so everybody was in bed by ten in the evening at the latest, and nobody ever turned on the tap during the night.

One night, however, the elder daughter—who was greedy and not very well behaved—got up at two in the morning, to go and see what she could find in the fridge. She found a roast chicken thigh, had a nibble at that, ate a mandarin, dipped her finger into a pot of jam and licked it; then she felt thirsty. She took a glass out of the dresser, went to the tap, turned it on… when suddenly, instead of water, out of the tap flew a tiny lady in a purple dress, fluttering dragonfly wings and clutching a wand topped with a golden star in her hand. The fairy (for it was she) perched on the edge of the sink and said in a musical voice:

“Hello, Martine.”

(I forgot to tell you that the girl’s name was Martine.)

“Hello madame,” replied Martine.

“Would you do something for me, Martine?” asked the good fairy. “Would you give me a little jam, please?”

As I said, Martine was a bit greedy and not at all well behaved. Nevertheless, when she saw that the fairy was nicely dressed and had dragonfly wings and a magic wand, she said to herself:

“Look out! She is a fine lady and I must be careful to be polite to her!”

So she replied, with a hypocritical smile:

“But of course, madame! Right away, madame!”

She took a clean spoon, dug it into the jam jar and held it out to the good fairy. The fairy fluttered her wings and hovered around the spoon, taking a few quick licks with her tongue, then she settled on the sideboard and said:

“Thank you, Martine. In recognition of your kindness, I shall give you a gift: for every word you say, a pearl shall fall from your mouth.”

And the fairy disappeared.

“Fancy that!” exclaimed Martine.

And, as she said these words, two pearls fell from her mouth.

The following morning, she told her parents the whole story, while spitting out a fair number of pearls.

Her mother took these pearls to the jeweller, who pronounced them of very good quality, although a little small.

“If she said some longer words,” suggested the father, “they might come out bigger…”

They asked their neighbours to tell them the longest word they knew. A well-read neighbour came up with the word antidisestablishmentarianism. They made Martine say it several times. She obeyed, but the pearls were no bigger. A little more elongated, perhaps, and a little more irregular in shape. What’s more, as it is a very difficult word, Martine could not say it well, and the quality of her pearls began to suffer.

“Never mind,” said her parents. “In any case, our fortune is made. From today, our daughter will no longer go to school. She will stay here at the table, and she will talk all day over the salad bowl. And if she dare stop talking, she’ll be for it!”

Being, among other faults, lazy and a chatterbox, Martine was delighted with this plan at first. But after two days, she had had enough of sitting still and talking in an empty room. After three days it was misery, and after four it was pure torture. On the evening of the fifth day, at dinnertime, she came inside, in a towering rage, and began to scream:

Actually, she didn’t say drat but something much worse. And with these three bad words, three great pearls appeared, enormous baubles, rolling down onto the tablecloth.

“What on earth?…” her parents chorused.

But they understood straight away.

“It’s simple,” said Martine’s father, “I should have thought of it. Every time she says an ordinary word, she coughs up a small pearl. But when it’s a naughty word, out comes a big one.”

From that day, Martine’s parents made her pronounce nothing but swear words over the salad bowl. At first, this made her feel better, but soon her parents were telling her off every time she said anything that wasn’t a swear word. After a week, her life had come to feel unbearable, and she ran away from home.

Martine walked the streets of Paris all day long, not knowing where to go. Towards evening, starving hungry and quite exhausted, she sat down on a bench. Seeing her there alone, a young man came and sat beside her. He had wavy hair, white hands and a very charming look to him. He spoke to her very kindly, and so she told him her story. He listened with great interest, all the while collecting in his cap the pearls she dropped while confiding in him. When she had finished, he looked tenderly into her eyes:

“Go on talking,” he said. “You are magnificent. If only you knew how I love hearing you speak! Let’s stay together, shall we? You can sleep in my room and we shall never leave each others’ sides. We shall be happy!”

Not knowing where else she could go, Martine accepted willingly. The young man took her home to his house, gave her food and a place to sleep, and the following morning, when she woke up, he told her:

“Now, my dear, it’s time to discuss serious matters. I can’t be feeding you to do nothing. I have to go out, so I’m locking you in. This evening, when I get back, I would like our big soup tureen to be full of big pearls—and if it is not full, you shall hear about it!”

All that day and all of those that followed, Martine was stuck indoors and obliged to fill the soup tureen with pearls. The young man with his kind eyes locked her in every morning and only came back in the evening. And if, when he came back, the tureen was not full, he beat Martine.

But let us leave Martine and her sad fate for a moment, and return to her parents’ house.

Martine’s younger sister, who was sensible and well behaved, had been deeply affected by the whole story, and had not the slightest wish to meet the fairy in the tap. Nevertheless, her parents, who bitterly regretted their eldest daughter’s disappearance, would say every evening:

“You know, if you’re thirsty in the night, you’re quite free to go and get a glass of water in the kitchen…”

Or:

“Now you’re a big girl. You could perfectly well do something nice for your parents. After all we have done for you…”

But Marie (I forgot to tell you that her name was Marie) pretended she had no idea what they meant.

One day, her mother had a brainwave. For dinner she served: split-pea soup, herring fillets and salt pork with lentils, and goats’ cheese for afters, which was all so salty that, when she went to bed, Marie could not sleep for thirst. For two hours she lay awake in bed, saying to herself:

“I won’t go to the kitchen. I won’t go to the kitchen…”

But in the end, she went, still hoping that the fairy would not come out.

Alas! Hardly had she turned the tap when out popped the fairy and fluttered down to perch on Marie’s shoulder.

“Marie, you’re such a good girl, give me a little jam!”

Marie was a very good girl, but she wasn’t stupid, so she answered:

“No thanks! I don’t need your gifts. You have made my sister miserable—that’s quite enough for me! Besides, I’m not allowed to go looking in the fridge while my parents are in bed.”

Out of touch with people for the last 1,500 years and no longer used to ordinary conversation, the fairy was offended by Marie’s reply. In her disappointment, she snapped:

“Since you are so unpleasant, my gift to you is that, with every word you say, a snake will fall from your mouth!”

*

Indeed, the very next day, with the first word Marie spoke to try to tell her parents about the fairy, she spat out a grass snake. She had to give up on speaking and instead wrote down what had happened during the night.

In a state of panic, Marie’s parents took her to see a doctor who lived two floors up in the same building. The doctor was young, friendly, well regarded in the neighbourhood and showed great promise in his career. He listened to the parents’ story, then he gave Marie his most delightful smile and said:

“Now, there’s no need to worry. It may not be all that serious. Would you like to follow me into my bathroom?”

They all went into the bathroom. There, the doctor said to Marie:

“Lean over the bathtub. Like that. And now, say a word. Any word.”

“Mummy,” said Marie.

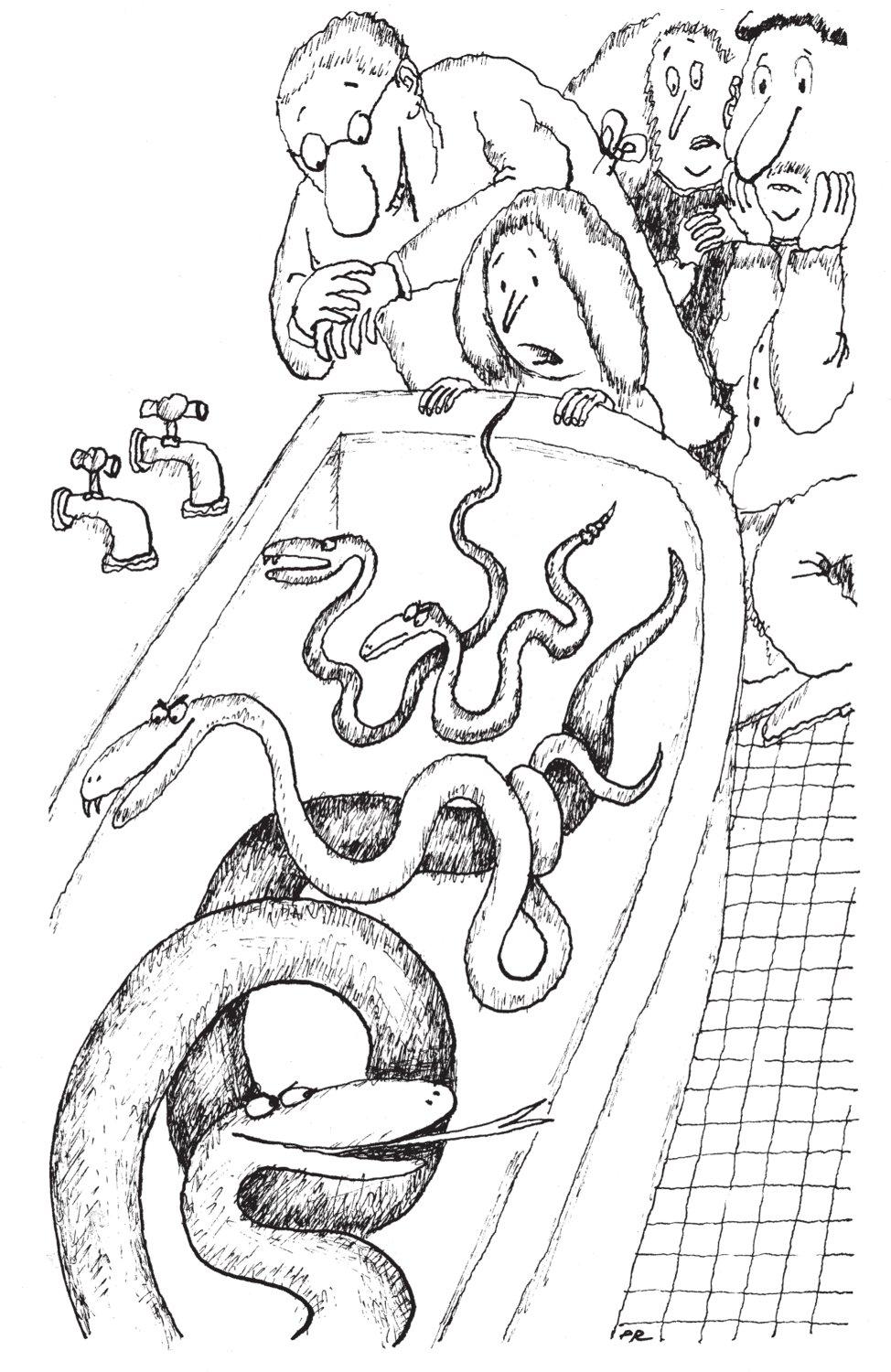

And a long grass snake slithered from her mouth into the bath.

“Very good,” said the doctor. “And now, say a swear word, just to see…”

“Come on,” said her mother, “just one naughty word for the doctor!”

Shyly, Marie muttered a swear word. And a young boa constrictor uncoiled into the bath.

“How sweet she is!” exclaimed the doctor, touched. “Now, my dear Marie, make one more effort and say something really mean for me.”

Marie realized that she had to obey. But she was so good that, even if she didn’t mean it, merely saying something nasty was hard for her. Still, she forced herself, and in a low voice pronounced:

“Dirty cow.”

Right away, two little adders rolled up in balls, flew from her mouth and fell with two soft thuds on top of the other snakes.

“It’s exactly as I thought,” said the doctor, gratified. “For a swear word, we get a big snake, and for a mean word, a venomous one…”

“But can you do anything for her, Doctor?” the parents asked.

“Do anything? Well, that’s easy! My dear monsieur, I am honoured to ask for your daughter’s hand in marriage.”

“You want to marry her?”

“If she will accept me, yes I do.”

“But why?” her mother asked. “Do you think that marriage will cure her?”

“I very much hope not!” replied the doctor. “You see, I work at the Pasteur Institute, developing venom antidotes. We’re rather short of snakes in my department. A young lady like your daughter is like a whole chest of pearls to me!”

So Marie married the young doctor. He was very good to her, and made her as happy as she could be while living with such a problem. From time to time, when he asked her, she said dreadful words so as to provide him with an adder or a cobra, or a coral snake—and the rest of the time she did not speak at all, which, luckily, did not bother her too much, for she was a simple, modest young lady.

Sometime later, the fairy in the tap wanted to find out what had happened to the two girls. She popped out to see their parents one Saturday evening after midnight, when they had come back from the cinema and were having a snack before going to bed. The fairy asked them about their daughters and they told her everything. Quite bewildered, she learnt that not only had she rewarded the bad daughter and punished the good one, but that, out of pure chance, the bad gift had turned out to Marie’s advantage, while the gift of the pearls had become a terrible curse for poor Martine and she had been punished far beyond what she deserved. Disheartened, the poor fairy said to herself:

“I’d have done better to sit tight and do nothing. I don’t have a clue how the world works these days; I get everything wrong and I can’t even foresee the consequences of my own actions. I must go and find a wizard who is wiser than me, so he will marry me and I can obey him. But where shall I look?”

Pondering this question, the fairy went out into the street, and she was fluttering along the pavement on rue Broca, when she saw a shop with its lights still on. It was Papa Sayeed’s cafe-grocer’s. Papa Sayeed himself was just putting all the chairs on the tables before going to bed.

The door was closed, but by making herself very tiny, the fairy was able to squeeze in under it. For she had spied, lying on a shelf, a great notebook and pencil case, which Bashir had forgotten to put away.

When Papa Sayeed had gone to bed, the fairy tore a page out of the notebook (have you noticed that there is often a page missing from Bashir’s notebooks?). Next she took some coloured pencils out of the pencil case and began to draw. Of course, Papa Sayeed had turned out the lights when he went to bed. But fairies have good eyesight and can even see colours in the middle of the night. So the tap fairy drew a wizard with a tall pointed hat and a long, black cloak. When the drawing was finished, she blew on it and began to sing:

Wizard of night

Seen without light

Traced by this fairy

Oh won’t you marry me?

The wizard’s face twitched and winced:

“No, I’d rather not,” he said, “you are too fat.”

“Then too bad for you!” retorted the fairy.

She blew on him again and the wizard stopped moving. She tore out another page (sometimes there are several pages missing in Bashir’s notebooks) and drew another wizard, with a grey cloak this time. She blew on this drawing and asked:

Wizard drawn

The colour of dawn

Traced by this fairy

Oh won’t you marry me?

But the grey wizard looked down to avoid her eyes:

“No, thanks. You’re far too skinny.”

“That’s your loss, then!”

The fairy blew on him again and once more he was nothing but a mere pencil drawing. Next she looked through the coloured pencils and realized there was only one she had not yet tried: the blue one. All the other coloured pencils had been lost!

“This time,” she thought, “I mustn’t mess it up!”

So, she took a third sheet of paper and, taking great care, drew a third wizard, this time with a blue cloak. When she had finished she gazed at him lovingly. Truly, this one was the handsomest of them all!

“Let’s hope he likes me!” she thought.

The fairy blew on him and began once more to sing:

Wizard of sunrise

Blue as the clear skies

Traced by this fairy

Oh won’t you marry me?

“Certainly,” said the wizard.

Then the fairy blew on him three times. At her third breath, the two-dimensional wizard thickened and then stepped out of the piece of paper. When at last he was standing upright, he took the fairy by the hand and the pair of them went out through the door and flew away down the street.

“Most importantly,” said the blue wizard, “I will take away Martine’s gift as well as Marie’s.”

“Will you really?” asked the fairy.

“It’s the very first thing to do,” he said.

There and then he recited a magical formula.

The next morning, Martine had stopped speaking in pearls. Realizing this, at first the apparently charming young man gave her a beating. Then, when he saw this wasn’t helping, he threw her out of his house. Martine went back to her parents, but the adventure had been a lesson to her and, from that day on, she was quite sweet and good.

*

On the same day, Marie stopping speaking snakes. This was a shame for the Pasteur Institute, but Marie’s husband was not a bit sorry, for now he had the pleasure of talking to her, and he realized that she was as intelligent as she was good.

The wizard and the fairy disappeared. I know that they are still around, but I don’t know where. They hardly do miracles any more, being very, very cautious these days, and they don’t mind in the least if anybody knows about them.

I almost forgot to add this: opening up the shop on the day after this memorable night, Madame Sayeed, Bashir’s mother, found her son’s pencils scattered all over a shelf, his big notebook open with three pages torn out and, on two of the pages, drawings of wizards. Very cross, she called her son and said severely:

“What is this mess? Aren’t you ashamed? You think we buy you all these notebooks so you can do this?”

However hard Bashir protested that it wasn’t his fault, nobody believed him.