A hundred yards from the church appears the main street of Nyamata, lined with majestic umuniyinya, known as “palaver trees.” A wooden sign for an AIDS-awareness campaign, the only advertising in town, marks the entrance to the marketplace, where soccer players orbit around balls made of banana leaves, pausing only during the high heat of siesta time.

Nyamata lives to the rhythm of two markets, large and small. The big one is held on Wednesdays and Saturdays, when, as day dawns, market women arrange their merchandise on cloths spread over the ground. As in all of Africa, the market is laid out by professions. In one corner gather the fishermen’s wives, near their smoked or dried fish strung on vines and protected from flies by a film of dust. Elsewhere, farm women offer their stems of bananas, mounds of yams, and bags of red beans. Farther along are heaps of shoes, old or new, single or in pairs. Sumptuous displays of cloth from Taiwan or Congo for pagnes—wraparound skirts—sit next to stacks of T-shirts and underwear.

From early morning on, the crowd leaves little room to maneuver for the porters’ slender wooden wheelbarrows or the women bearing wicker trays, who replenish the stocks of merchandise. Music is sold a little off to one side, in the street. The shop consists of a cassette player sitting on a stool, for sampling, and three tables covered with tapes of hymns, folk melodies from the African Great Lakes Region, the melancholy songs of the popular Rwandan singer Annonciata Kamaliza, plus more lively hits from Congo and South Africa. Céline Dion and Julio Iglesias bring music from the world at large.

This market is rather cheerful and modest (not to say meager), without any jewelry, musical instruments, secondhand dealers, sellers of paintings or sculptures, without much haggling or chatter, or too many disruptive scenes, either.

As for the little market, it is essentially alimentary and is held every day on some bumpy wasteland behind the square. Heaps of manioc surround the milling shed. Goats are for sale near the slaughterhouse, the front of which serves as a butcher’s stall. Not far away are the veterinary pharmacy and clinic, and the cabaret frequented by the local vets. Charcoal is sold near stacks of firewood. One may also find peat, manure, the men who resole flipflops, jerry cans of banana beer, jugs of milk curds, piles of trussed chickens, pyramids of salt and sugar, and the ubiquitous sacks of beans.

The marketplace is surrounded by stores painted green, blue, and orange, colors faded by the heat and dust. Half the shops are closed and have been falling apart since the war. The others house hairdressers’ salons and dim cabarets where men nurse their banana beers. In Nyamata, there are no more newspaper stands, and the only bookstore left is the religious one, where people go to get photocopies. Beneath the shop awnings, near the displays of fabric and the photography studios, seamstresses bend over their black and gold sewing machines, splendid Singers or Butterflys. They mend a torn pair of trousers, cut shirts to measure, hem cloth for pagnes, all in the time it takes their customers to visit the church, the health center, or the town hall.

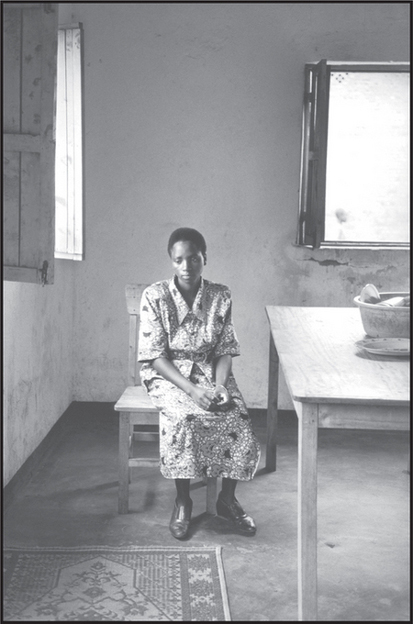

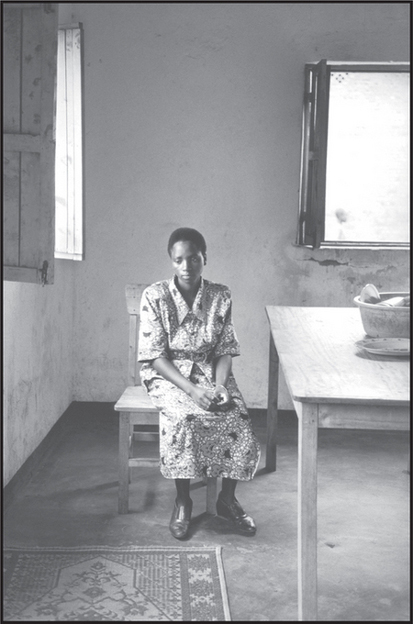

Twice a week, Jeannette Ayinkamiye comes down from the hill of Kanazi to sew in the marketplace, among twenty or so machines that click along in a diligent silence interrupted now and then by laughter or consultations. On those days, Jeannette wears her long Sunday dress with puffy sleeves, but no jewelry, braids, or curls, which are forbidden by her Pentecostal pastor.

The rest of the week, except for Sunday, she farms a family plot. She abandoned her studies after the genocide. She lives in a spotless brick house with two younger sisters and two orphans in her care, whom she feeds, clothes, and sends to school. She had never spoken with a foreigner before, but at our first meeting, she agrees without hesitation to tell her story. Whenever she speaks, painfully and repeatedly, about the death of her mother, she seems courageously determined to carry on.