The year of Independence, my parents were driven from their birthplace when a Belgian government truck brought them to the hill of Kibungo to clear a section of bush. Here, we never sincerely mixed with the Hutus nearby. People lived among their own ethnic group; no one quarreled with anybody. There were many inequalities in our dealings together, yet we did have an understanding.

A month or two before the genocide, however, alarming news of massacres began to spread through our neighborhoods. Behind our backs Hutu neighbors were yelling, “The Tutsis, those Tutsis, they absolutely must die!” And they spat other threats like that at us. New faces were appearing among the houses, and we would hear the interahamwe training in the forest, shouting encouragement to one another.

The interahamwe began to hunt Tutsis on our hill on April 10. Since they had never gone so far as to kill families in the churches, that same day we moved out in a long procession to seek refuge in the church in N’tarama. We waited five days. As our brethren continued to gather, we became a great crowd. When the attack began, an onslaught of noise confused the full picture of the massacre, but I did recognize many faces of neighbors who were killing nonstop. Very soon I felt a blow: I fell between two benches, with chaos all around. When I woke up, I checked to be sure I was not dying. I made my way through the bodies, then escaped into the bush. Among the trees, I came upon a band of fugitives and we ran all the way to the marshes. I was to remain there for one month.

Then we lived out days beyond misery. Each morning we went to hide the littlest ones beneath the swamp papyrus; then we would sit on the dry grass and try to talk calmly together. When we heard the interahamwe arrive, we ran to spread ourselves out in silence, in the thickest foliage, sinking deep into the mud. In the evening, when the killers had finished work and gone home, those who were not dead emerged from the marsh. The wounded simply lay down on the oozing bank of the bog, or in the forest. Those who still could went up to the school in Cyugaro, to doze off in a dry place.

And in the morning, quite early, we’d trudge down to go back into the marshes, covering the weakest among us with leaves to help them hide. Out in the swamp, we came upon many naked women, because the Hutus stripped their dead victims of any pagnes in good condition. Truly, such sights spilled angry tears from our eyes.

I had found my fiancé again. Théophile and I would glimpse each other on the paths; we were sometimes together, but we no longer lived with any intimacy. We felt too shattered to find real words to say or any gentle ways to touch one another. I mean that if we happened to meet, it no longer much mattered, to either one of us, since more than anything else, we were both just trying to save our own lives.

One day, I got caught in my watery hiding place. That morning I had run into the marsh behind an old woman I knew. We were crouching silently in the water. The killers discovered her first, and I saw them cut her without bothering to drag her from the bog. Then they searched the surrounding foliage with the utmost care, because they knew all too well that a woman never hid just by herself. They found me, holding my child in my arms. They slaughtered my child. I asked to go out onto the grass and not die in the filth of slime and blood where the old woman was already lying. There were two men; I have not forgotten one feature of their faces. They dragged me into the papyrus and clubbed me, laying me out straightaway with a first blow full on the forehead, without cutting my throat. Often, they would leave the wounded in the mud for a day or two before returning to finish them off. As for me, though, I believe they simply forgot to come back there, that’s why they botched the job.

I was unconscious for a long time. Then Théophile and some other fugitives found me near death and comforted me with a drink of water. I was no longer more than half alive, a prey to a bad fever and worse thoughts, but I was not afraid of death anymore. The wounds chose to spare my life, in any case, and I managed to get well on my own. In the evenings, Théophile tended me, fetching me handfuls of food from the fields. I finally brought myself back to life, returned to the business of survival, and rejoined my team. In the marshes, we tried to stay with the same group of acquaintances, to find easier comfort among ourselves. If too many people died, though, you’d have to find a new team.

During the evening gatherings, we heard no news from anywhere because the radios had stopped working, except in the killers’ houses. Still, we did understand through hearsay that the genocide had spread throughout the country, that all Tutsis were suffering the same fate, that no one would come to save us anymore. We thought we were all doomed. Me, I now worried not about when I would die—since die we would—but about how the blows would slice into me and for how long, because I was terrified of the agony machetes cause.

I heard later that a small number of people committed suicide. Especially women, who would feel their strength fail and preferred the rushing river to getting hacked up alive. Choosing this death demanded too desperate a madness, because along the path that led to the Nyabarongo River there was an even greater risk of being caught by machetes.

On the day of the liberation, when the inkotanyi of the RPF7 came down to the edge of the marshes and shouted that we could come out, no one wanted to move from beneath the papyruses anymore. The inkotanyi yelled their lungs out trying to reassure us, while we stayed under the leaves without a word. I personally think that at that moment, we survivors did not trust a single human being on this earth.

As for the inkotanyi, when they saw us finally creep out like mud beggars, they were stunned as we passed by. Most of all, they seemed bewildered, as though they were wondering if we were actually still human after all that time in the marsh. They were quite disturbed by our gauntness and stench. It was a disgusting situation, but they tried to show us the utmost respect. Some chose to line up in ranks, standing at attention in their uniforms, their eyes fixed upon us. Others decided to come over to support the weakest survivors. The inkotanyi were clearly having trouble believing all this. They wanted to appear sympathetic, but they hardly dared whisper to us, as though we could no longer truly understand reality. Except, of course, for some gentle words of encouragement.

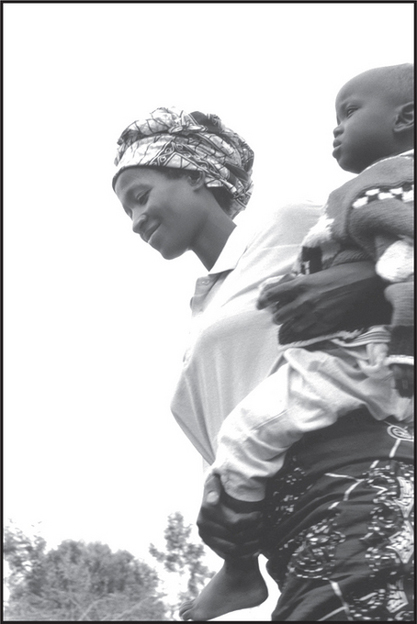

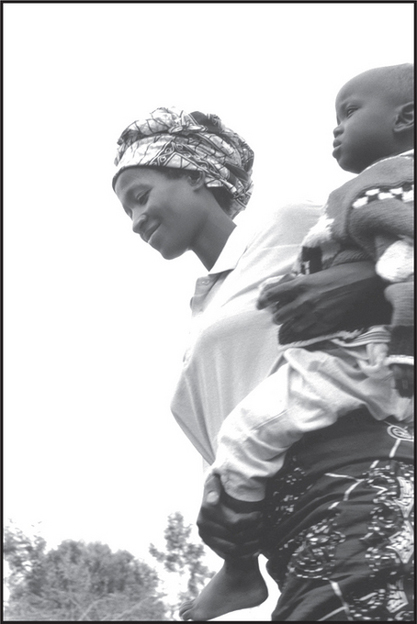

Four months after the genocide, I married Théophile. We behaved as if nothing had changed between us, despite what had happened. And that’s how we came back, saying softly what had to be said softly, and loudly what was to be said loud and clear. We live in a three-room terre-tôle house with our two little children and four orphans. The orphans, there’s no point anymore in teaching them about the genocide—they’ve seen the worst of the real thing. My two young children, they’ll learn the vital truth about the genocide later on. In any case, I think that from now on a gulf in understanding will lie between those who lay down in the marshes and those who never did. Between you and me, for example.

We talk with our neighbors almost every day about the killings, otherwise we dream of them at night. Talking doesn’t soothe our hearts, because words cannot return us to times gone by, but keeping quiet encourages fear, withdrawal, and suchlike feelings of mistrust. Sometimes we joke about all that, we laugh, and yet we come back, in the end, to those fatal moments.

Myself, I don’t wish to cry vengeance, but I hope that justice will offer us our share of peace of mind. What the Hutus did is unthinkable, especially for us, their neighbors. Hutus have always imagined that Tutsis were haughtier and more polished in their manners, but that’s plain silly. Tutsis simply behave more temperately, in good times and bad. They are just more reserved by nature. It is also true that Tutsis prepare better for the future, it’s part of their tradition. But in any case, in the Bugesera, Tutsis have never harmed Hutus. They haven’t ever even spoken slightingly about them. The Tutsis were just as poor on the hills, they did not have larger properties, or better health and education than the Hutus.

I don’t know if it makes any difference to say that now. I do it with some misgiving, because too many people are no longer here to speak for themselves, while fate has loaned me the opportunity to speak in my own voice.

Hutus still suffer from a bad idea of Tutsis. The truth is, it’s our physiognomy that is the root of the problem: our longer muscles, our more delicate features, our proud carriage. That is all I can think of—the imposing appearance that is our birthright.

What the Hutus did, it’s more than wickedness, more than punishment, more than savagery. I don’t know how to be more precise, because although you can discuss an extermination, you cannot explain it in an acceptable way, even among those who lived through it. New questions always come at you out of nowhere.

My family is dead, and because of my headaches, I can no longer farm out in the sun. Since I was ready to go, I don’t know why God chose for me not to die, and I thank Him. But I think of all those who were killed, and those who did the killing. I tell myself, the first genocide, I didn’t believe it possible, so, regarding the likelihood of another one, I have no answer. Frankly, I expect that the suppressions of Tutsis are over for our generation; as to afterward, no one can predict our future. I know that many Hutus criticized those massacres, which they blamed as obligations. I see some Hutus who lower eyes weighed down by guilt. But I cannot glimpse much goodness in the hearts of those who are returning to the hills, and I hear no one asking for forgiveness. In any case, I know there is nothing that can be forgiven.

Sometimes, when I sit alone on a chair on my veranda, I imagine a possibility. If, on some distant day, a local man comes slowly up to me and says, “Bonjour, Francine. Bonjour to your family. I have come to speak to you. So here it is: I am the one who cut your mama and your little sisters,” or, “I am the one who tried to kill you in the swamp, and I want to ask for your forgiveness,” then, to that particular person, I could reply nothing good. A man, if he has drunk one Primus beer too many and he beats his wife, he can ask to be forgiven. But if he has worked at killing for a whole month, even on Sundays, how can he hope for pardon?

We must simply take up life again, since life has so decided. Thornbushes must not invade the farms; teachers must return to their school blackboards; doctors must care for the sick in the health clinics. There must be strong new cattle, fabrics of all kinds, sacks of beans in the markets. In that case, many Hutus are necessary. One cannot line up all the killers in the same row. Those who were overwhelmed by events, they can come back from Congo and the prisons one day, and return to their farm plots. We will begin to draw water together again, to exchange neighborly words, to sell grain to one another. In twenty years, fifty years, there will perhaps be boys and girls who will learn about the genocide in books. For us, however, it is impossible to forgive.

When you have lived a waking nightmare for real, you no longer sort through your daytime and nighttime thoughts the way you did before. Since the genocide, I always feel hunted, day and night. In my bed, I turn away from the shadows; on a path, I glance back at forms following me. When I meet a stranger’s eyes, I fear for my child. Sometimes I see the face of an interahamwe down by the river and tell myself, Look, Francine, that man—you’ve seen him before in a dream … and I remember only afterward that this dream was that time, wide awake, back in the marshes.

I think that for me it will never end, being despised for my Tutsi blood. I recall my parents, who always felt persecuted in Ruhengeri. I endure a kind of shame over feeling hunted like that a whole life long, just because of what I am. The moment my eyes close upon that, I weep inside, from misery and humiliation.