In school, I’d never heard one ethnic reproach. We kicked the soccer ball around without any hassles among ourselves, whenever time gave us a little break. On April 10, after Mass, some neighboring Hutus came to our house near the river to order us out, because they wanted to take it over, although without killing us. We went up right away to Kibungo, to stay with Grandfather.

Soldiers arrived the next day. When my uncle tried to sneak off, he didn’t get far. They shot him dead. So then we fled to the church at N’tarama: Papa, Mama, my eight brothers and sisters, Grandfather and Grandmother. The interahamwe prowled around in the little wood surrounding the church for three or four days. One morning, they entered in a group, behind some soldiers and local policemen. They made a rush and began hacking people up, indoors and out. Those who were slaughtered died without a word. All you could hear was the commotion of the attacks—we were almost paralyzed, caught up in the machetes and the yelling of the attackers. We were already just about dead before the fatal blow.

My first sister asked a Hutu she knew to kill her without any suffering. He said yes, dragged her by an arm onto the grass, and struck her once with his club. But a close neighbor, called Hakizma, shouted that she was pregnant. He sliced open her belly with a knife, opened her up like a sack. That is what human eyes have seen and no mistake.

Picking my way through the bodies, I had bad luck: a boy managed to get me with his iron bar. I collapsed onto the corpses, I didn’t move, I made deadman’s eyes. At one point, I felt myself being lifted and thrown. Other people landed on me. By the time I heard the interahamwe leaders whistle the signal to leave, I was all covered with dead people.

It was toward evening that some brave Tutsis from our area, who had run off into the bush, came back to the church. Papa and my big brother untangled us from the heap, me and my last sister, who was all bloody and died a little later in Cyugaro. In the schoolhouse, folks put dressings of healing grasses on the wounded. In the morning, we all decided to hide in the marshes. That’s what we did every day, for a month.

We’d go down very early. The little ones hid first; the grown-ups stood watch and talked about what was happening to us. They hid last, when the Hutus arrived. Then, it was killing all the day long. At the beginning, the Hutus tried tricks in the papyrus. For example they’d say, “I recognized you, you can come out,” and the most innocent ones would get up and be massacred where they stood. Or the Hutus would follow the faint cries of tiny children, who couldn’t stand the mud anymore.

When the hunters found rich people, they would take them away to make them show where they’d hidden their money. Sometimes the killers would wait to collect a large group, to cut them all together. Or they’d gather a whole family so they could cut them in front of one another, and that spilled a big pool of blood in the marsh. Those still alive would go later to identify those who had been unlucky, by looking at the bodies in the puddles.

In the evenings, people would seek company in Cyugaro by acquaintance: neighbors together, young people together.… At first, small groups gathered to pray. Even folks who had never had a long habit of prayers, it seemed to comfort them to believe nevertheless in a little invisible something. But later on, they lost strength or faith, or they simply forgot, so no one bothered with that anymore.

The oldsters liked to go off to one side to talk over what was happening. There were some young people who would bring them small amounts of food that were just enough. But certain elders had no more children to help them. Every evening, they felt a growing collapse, because they no longer had the energy to dig in the ground and get by. Given their great age, they had too much pride to beg. So, one evening, they would say, “Well, now I’m not good for anything, tomorrow I’m not going down into the marsh.” That’s how many let themselves perish, sitting at dawn against a tree, without fighting back until the end of their old age.

On certain evenings, when the evildoers had not killed too much during the day, we would gather around glowing embers to eat something cooked; on other evenings, we were too downhearted. In the marsh, the next day at sunrise, we’d find the same blood in the mud, corpses rotting in the same places. The criminals preferred to kill the most people possible without bothering with burial. They must have thought they had all the time in the world, or that they weren’t burdened with that stinking chore because they had already done their job. They also thought that those filthy bodies in the muck would discourage us from going to ground. We did try, though, to bury a few dead relatives, but it was rarely possible, we never had enough time. Even those animals that could eat them had run away from the tumult of the killings.

Those corpses bothered us so much that even among ourselves, we dared not speak of them. They showed us too harshly how our lives would end. I’m trying to say that their decay made our deaths more brutal. Reason why, every morning, our dearest wish was simply to make it one more time to the end of the afternoon.

When the inkotanyi came down to the marshes, to tell us that the massacres were over, that we would live, we didn’t want to believe them. Even the weakest refused to leave the papyrus. Without a word, the inkotanyi went back the way they had come. They returned with a boy from N’tarama, who began yelling, “It’s true! They’re the inkotanyi, it’s the RPF! The interahamwe are running off in a panic! Come out, you won’t be killed anymore.…” We stood up. We saw one another on our feet, all of us in the middle of the afternoon, for the first time in a month.

At the assembly, a soldier explained to us in Swahili: “Now you are safe; you need to lay down your knives and machetes here. You don’t need them anymore.” One of us answered, “Machetes? We’ve had none since the beginning. All we have on our bodies is sickness, and we cannot lay that down. Even clothes—we haven’t any others.” Me, I was wearing only a torn pair of shorts, the same ones from the first day.

We left the worst-off survivors in the shade, so as to fetch them later in vehicles. We were escorted to Nyamata. After waiting a few days, my big brother and I went home to our land in Kiganna. Since our parents’ house had collapsed, we moved here, to Kibungo, to the home of the grandfather who had been killed in the meantime. Anyway, it was too heavy a burden to live beside the river where we had been happy as a family.

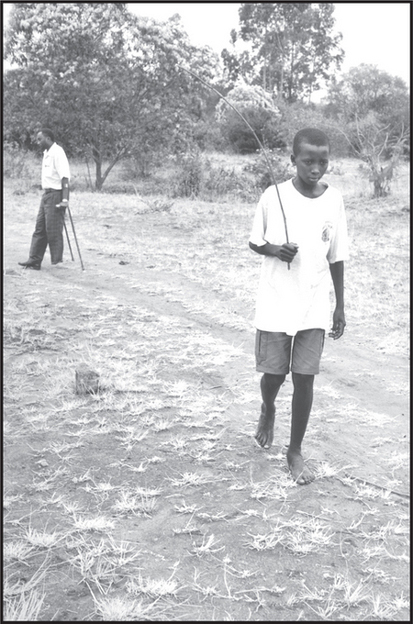

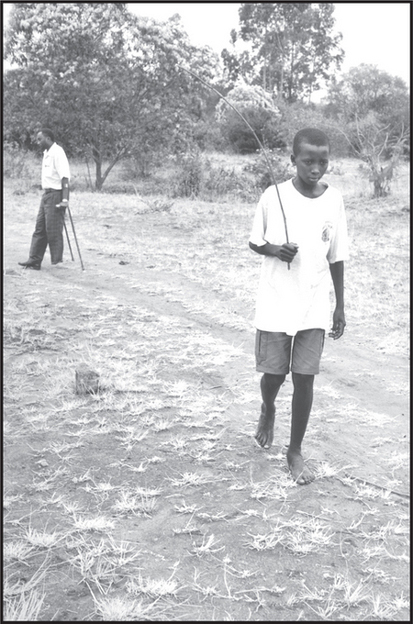

Papa had twenty-four cows and five goats. We caught three cows in the bush, thanks to their distinctive patches of color. I live now with my big brother, Vincent Yambabaliye. I prepare his bowl for him morning and evening, I herd our cows and three others belonging to neighbors, out in the bush, while he farms our property. I don’t like to go down into the valley, because I’m afraid the cows might trot off to the herds of the shopkeepers of Nyamata. We no longer have enough cattle to gather them around a paid cowherd. That’s what is stopping my return to education, and every day it makes me sad.

In Kibungo, I have brought myself more or less back to life, but the sorrow of losing my family always takes me by surprise. I live too desolate a life. Off with the cows, I’m afraid of the rustlings in the bush. I would like to go back to the school-bench and begin learning again so that I could see something of a future for myself.

In Kibungo, when evening comes, it’s clear that life has broken down. Many men wait impatiently to drink their Primus or urwagwa, our banana beer. They drink, and they no longer think about anything interesting: they say silly things, or nothing at all. As if they wanted only to drink on behalf of those who were killed, those who can’t drink their share with them anymore, those whom, above all, no one wants to forget.

The genocide in Kibungo—we won’t forget one scrap of its truth, because we share our memories. In the evening we often talk about this, we go over details with one another and try to be precise. Some days, we recall the most distressing moments, the sinister interahamwe; other days, we recall calmer times, when they had taken time off from our side of the marsh. We poke fun at one another, and then right away we go back to the most painful scenes.

Still, over time, I do feel that my mind sorts through my memories as it pleases, and I can do nothing about that. Same thing for us all. Certain episodes are much retold, so they swell with all the additions from one or another of us. Such episodes remain transparent, so to speak, as though they had happened yesterday or only last year. Other scenes are neglected, and they darken as in a dream. I would say that certain memories are perfected, and others are abandoned. But I know that we remember better now than before what happened to us personally. We’re no longer interested in inventing, or exaggerating, or concealing, as at the liberation, because we aren’t dazed anymore by fear of the machetes. Many people are less terrified or undone by what they have experienced. Sometimes we do talk overmuch among ourselves, and I get scared when I lie down in my bed.

When I pass the church in N’tarama, I look the other way going by the railings, and I avoid the hut of the Memorial. I don’t want to see the rows of nameless skulls that may be my family’s bones. Sometimes I go down to the edge of the marsh, I sit on a tussock of grass, and I look at the papyrus. Then, I see the interahamwe again, chopping with their machetes at whatever they found during the day. This awakens a sadness in me, and foreboding, but no hatred.

To feel hate, you must be able to direct it at definite names and faces. For example, those you recognized when they were killing—they must be cursed in person. But in the marshes, the killers worked in columns, we almost never made out their faces from beneath our leaves. Me, in any case, I can no longer imagine recognizable features. Even the face of my sister’s murderer, I’ve forgotten it. I believe that hatred goes to waste against a mob of strangers. It’s the opposite for fear. In a way, that’s what I feel.

If I try to find a reason for this butchery, if I try to understand why we had to be cut, my mind takes a beating, and I waver in doubt over everything around me. I will never figure out the thinking of the Hutus who lived with us. Even the thoughts of those who did not strike us down directly, but said nothing. Those people wanted to hasten our deaths to take over everything. I see only greed and brute force as the roots of that evil.

I cannot grasp why our ethnic group is accursed. If I were not stopped short by poverty, I would travel far from here, to a country where I would go to school all week long, and play soccer on a nice grassy field, and where no one would want to mistrust me and kill me, ever again.