I was a young man when we were exiled to the Bugesera. That was in 1959: the last mwami, Mutara III, had just drawn his final breath, and Hutus had taken over all positions of authority after the first general elections in Rwanda. I had finished my studies at the famous Teacher’s School in Zaza. I had found a job in the volcanic region of Birunga, but no sooner had I walked into my classroom than I was shoved out of it, and I began to worry about what I was hearing behind my back.

In December of that evil year, Bahutu extremists marked the doors of Batutsi homes with paint in broad daylight, and returned during the night to set them on fire. We had therefore taken refuge with neighbors at the Catholic mission, where no one dared come after us in those times. As the days passed, we became too numerous, crammed in shoulder to shoulder. The Belgians did try to help us, but their major concern was the lack of proper hygiene. So one morning, a Belgian administrator turned up and asked us to write a list of the countries where we wished to go into exile. I myself had heard nothing good about foreign lands, I had no family in Burundi or Tanzania, so I wrote down my own country, Rwanda. Many of us had done the same thing. “Fine,” the administrator concluded. “You’ll go to the Bugesera, since it’s uninhabited.”

That region of the Bugesera, we knew it only by name. The authorities brought army trucks into the mission courtyard. I climbed into a rubaho, a dump-truck with a wooden body, along with my wife, my younger brother, and my grandma. We were allowed the clothes on our backs and nothing more: neither utensils, nor blankets, nor books. That is how we traveled nonstop through the night, without knowing what awaited us. I never looked back down that road and I have never again set the smallest toe in the prefecture of my childhood. We had crossed the bridge at the Nyabarongo River at first light. In those days, it was only two tree trunks, a kind of log ferry that you pulled on a rope to cross over. More trucks were waiting for us on the other side.

We set eyes on a land covered with savannas and marshes: we were entering the Bugesera. I thought, They are dumping us here to abandon us alive in the arms of death. Without exaggeration: the swarming tsetse flies darkened the brightness of the sky. I still believe the authorities assumed that those terrible tsetse would be the end of us. We saw not one living creature anywhere on the trail. Then the first straw huts appeared. The only wooden-plank lodgings in Nyamata were the mission office, the district courthouse, the administrator’s home, and an army camp in the Gako Forest.

After a week, we teachers set out in a small group to reconnoiter. While we were crossing some vast savannas, we suddenly found ourselves staring at a herd of elephants. We about-faced and took to our heels, because until then we’d only been around chickens and goats.

Later, we happily learned that here and there, Batutsi cattlemen and Bahutu farmers were living quite properly as neighbors on some remote hills over by Burundi. We camped out for a year, sheltering in huts made from cardboard and sheet metal. Actually, we were nourishing a frail hope that the situation would calm down, and that we could return to our ancestral homes. Alas, Batutsi refugees and bad news arrived with increasing frequency from the other prefectures.

Since we were surviving despite our poverty, the local administration gave us permission in 1961 to disperse and to claim land in the bush, as part of the celebration of the first anniversary of the Republic. So we signed up on a list of recipients, and when someone’s number hit the first line, he went off to choose his five acres, which he could clear for himself.

Life was hard. We had to rip out bushes and tall shrubs amid the dust, dig through a thick crust of earth with wooden tools, plant sorghum and banana trees, build huts of mud and palm leaves. We had to defend ourselves against wild animals with bows and spears, and sometimes staves. Near my land, my eyes have seen the lion, the leopard, the spotted hyena, and the buffalo. There was no spring, and our stomachs were not used to drinking the stagnant water of the marshes, so many of us died of typhoid, dysentery, or malaria. To survive, we had to callus up our hands on tool handles, toil endlessly in the sun and rain, and bring ever more children into the world. Then, we began to gain a tiny foothold in the markets. Our meager crops were purchased for shops in Kigali; with our small savings, we were able to buy a few baby goats. Local Batutsis started to offer us cows, out of kindness or to wed our prettiest girls.

We had always grouped ourselves according to acquaintance. N’tarama Hill was inhabited by newcomers from Ruhengeri, and the opposite slope by those from Byumba, while those from Gitarama settled lower down. On the hills, we gathered in large families, meaning, to use your vocabulary, in tribes. With the passing years, when the arrivals of Bahutus later increased, they did the same on other hills, and we did not mix much because of the distances. The Bahutus began coming above all as a result of directives from the minister of agriculture, when important officials realized that the bush of the Bugesera was being populated and cultivated. It was in 1973 that the Bahutus became as numerous as the Batutsis. Those Bahutus were hard workers, tough, and some of them set themselves up with savings. We quickly came to an understanding because we needed their money and their strong arms. As fellow farmers, we hardly ever shared a beer, but we spoke freely to one another, with propriety. We came from the same agriculture: beans, manioc, bananas, yams, the use of hoes and machetes. The Bahutus were better planters. As for the Batutsis, they raised cows, unlike the Bahutus, who never had the patience for them.

Since there were not many schools open to Batutsis, due to the admissions quotas in each district, we teachers would have the pupils sit in a circle in the shade of tall leafy trees, and we would improvise lessons right there in the dust. In the Bugesera, the authorities and the administration were Bahutu, as were the soldiers, the mayors, and those who controlled the purse strings. So, as soon as a Batutsi caught on to some learning, he became an instructor and taught school to Batutsi children.

That is how we teachers became very poorly regarded by the authorities, who were clearly jealous. They did not dare silence us directly, but the moment any killings began, teachers appeared high on the list, on the pretext that they had ties to the inkotanyi. The inkotanyi were the Batutsi rebels, the underground force in Burundi that launched attacks on Rwanda. Whenever the inkotanyi attacked the Bahutus, the army would go kill Batutsis as a punishment.

That’s how things were. They would kill, in order: the families of men who had joined up in Burundi; then teachers, for reasons I’ve already explained; finally, the well-off farmers, so as to distribute their lands and crops to the latest Bahutu arrivals. One year would be burning-hot; the next year, quite calm. For example, 1963 was a year when thousands were murdered, as a natural response to the many rebel expeditions. 1964 was a quiet year. 1967 was disastrous in the way of deaths: that year, soldiers threw hundreds of Tutsis alive into the Urwabaynanga, a great pool of oozing mud over by Burundi, where you can actually go fish out the proof. In 1973, they went as far as to kill students in their classrooms.… The massacres were unpredictable. That’s why, even when the situation seemed peaceful, both our eyes never slept at the same time.

And yet, we Batutsis, we had driven off the wild animals, conquered the tsetse, and learned to submit to the authorities. In spite of the ethnic friction, our villages were multiplying, Batutsis were holding their own in numbers against the Bahutu population, and their herds were increasing. Certain Batutsis were becoming a bit wealthy, with Bahutus beginning to work for them. Nyamata was growing fast; the shops were mixed, but the best-stocked ones were Batutsi. Cabarets were appearing, and immediately became quite popular. Life was hard, but did not seem too bad.

There were many excellent people among the Bahutus. I remember one day, I was already tied to a tree before a row of army guns, because I bore the tribal name of a rebel leader. The only thing left to do was die, but I kept proclaiming my innocence. A captain on inspection tour happened to notice me at death’s door and shouted to the soldiers, “I know that man’s voice: he is first-named Jean-Baptiste, from Cyugaro, he’s a good teacher, he has nothing to do with the rebel commandos,” and he had the ropes cut. Many Bahutus grew ever more suspicious of Batutsis, though, on account of the inkotanyi. And because decent farmland, well, there was less and less of it available.

This discord grew poisonous after the authorization of a multi-party electoral system in 1991. When meetings began, public discussion became too dangerous; the exchange would boil up quickly, with the risk of injury every time. Interahamwe arrived to parade along the roads and paths, and they swaggered around in the cabarets. The radio called the Batutsis cockroaches; Bahutu politicians predicted at gatherings that the Batutsis would die. They were dreadfully afraid of the inkotanyi and a foreign military invasion. I believe that was when they began to think about the genocide.

In 1992, the tally of Batutsi corpses in the forest came to four hundred without the slightest protest from the chief of police. When the war broke out two years later, we were already accustomed to killings. I myself anticipated the usual tragedy, nothing more. I thought, Things are too hot to take the main road, but if we don’t go down off the hill, we might manage. After the massacre in the church, I realized that our plight had become deadly. That day, I joined the stream of fugitives flowing down to the Nyamwiza Marsh to crouch in the mud.

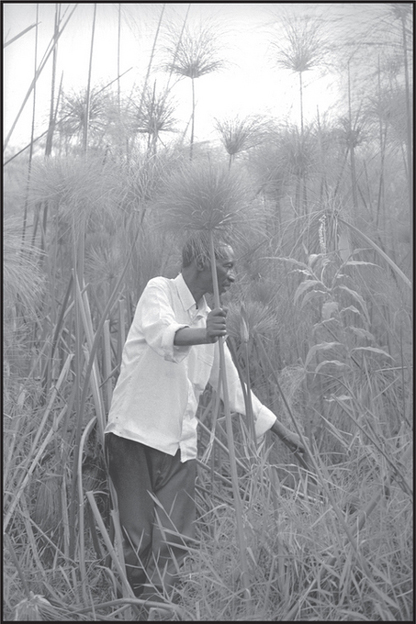

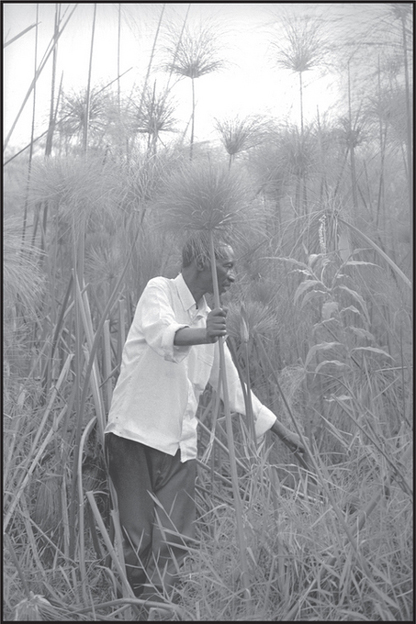

In the beginning, deep in the papyrus, we hoped help would come. But God Himself showed that He had forgotten us, so all the more reason for the Whites to do the same. Later, each day we hoped only to make it to the next dawn. Down in the marshes, I saw ladies crawling through the mud without a whimper. I saw a nursling sleeping forgotten on his mama, who had been cut down. I heard people with no muscle strength to walk at all announce their longing to eat some corn, one last time. Because they knew perfectly well that they would be dispatched the next day. I saw the skin fold into wrinkles on people’s bones, week after week. I heard songs tenderly hummed to comfort the moans of death.

In the forest, I happened upon the news of the death of my brother’s two children, who had passed the national university entrance exam. In the swamp, I learned of the deaths of my wife, Domine Kabanyana, and of my son, Jean-Sauveur. My second son died behind me while we were running through the marsh. We’d been trapped by a surprise attack, but had tried to escape our pursuers anyway. His flight ended when he stumbled over a tussock of thornbushes; he cried out one word, I heard the first blows, I was already far away.… He was in the fourth grade.

You must understand that we fugitives, although we lived “all for all” in our evening camp, were forced to live “everyone for himself” during our flights through the swamp. Except, of course, for the mamas carrying their little ones.

In the evening, four families gathered in my house in Cyugaro. We no longer spread mats and mattresses on the floor because the interahamwe had stolen them. We engaged in a little conversation, especially details about the day’s happenings or words of comfort. We did not argue, we teased no one, we did not mock the women who had been raped, because all the women expected to be raped. We were fleeing the same death, we endured the same fate. Even former enemies no longer found a reason to quarrel, because there was just no point in that anymore.

We would talk a bit, in those days, about the why of that damned situation, and we would come up against the same answers. The Bugesera, once deserted, had become crowded. The authorities were scared of being hunted down by the “Ugandans’ RPF.” The Bahutus were making eyes at our lands.… But all that did not explain the extermination, and still doesn’t today.

I personally can point to an historical anomaly. The history books about the Belgian colonization taught us that the Batwa pygmies with their bows were the first inhabitants of Rwanda. Then the Bahutus arrived, with hoes. The Batutsis followed with their cattle, acquiring too much land because of their vast herds. But here, in our region of the Bugesera, the arrivals occurred in precisely the opposite order, since the Batutsis came first, clearing the land as pioneers, bringing nothing in their hands. And yet, the genocide in the Bugesera was just as efficient as it was everywhere else. Therefore, I refute those historical explanations. I think that the history dictated by the colonial authorities programmed the Bahutu yoke set upon the Tutsis—a program that through bad luck, if I may put it that way, turned into genocide.

Today I suffer from poverty in many ways. My wife is dead and I have lost everyone in my family except two children. I had six cows, ten goats, thirty hens; now my yard is empty. My close neighbor is dead; the man who offered me my first cow is dead. Out of the nine teachers in the school, six were killed, two are in prison. After such long years, becoming a true friend to new colleagues is a trying and awkward thing, when one has lost the familiar people of the past. I married again, to one of my wife’s younger sisters, but I live a life that no longer interests me. At night, I traverse an existence all too crowded with my dead relatives, murder victims who all talk among themselves but ignore me, not even bothering to look at me anymore. By day, I suffer from a different kind of loneliness.

What happened in Nyamata, in the churches, in the marshes and on the hills, were the abnormal actions of perfectly normal people. Here’s why I say that. The principal and the inspector of schools in my district joined in the killings with nail-studded clubs. Two teachers, colleagues with whom I used to share beers and student evaluations, pitched in to help, so to speak. A priest, the mayor, the assistant chief of police, a doctor—they all killed with their own hands.

These intellectuals had not lived at the time of the Batutsi kings. They had not been robbed or victimized in any way, they were under no one’s obligation. They wore pressed cotton trousers, they had no trouble sleeping, they traveled around in cars or on mopeds. Their wives wore jewelry and knew city manners, their children attended white schools.

These well-educated people were calm, clearheaded, and they rolled up their sleeves to get a good grip on their machetes. So, for someone who has taught the humanities his whole life long, as I have, such criminals are a fearsome mystery indeed.