My parents were small farmers and livestock breeders. They gave me permission to finish my first year in secondary school before starting to look for a husband. In our customs, girls marry earlier when the parents aren’t rich.

One day, I came to visit a maternal aunt in Nyamata. On the main square, a gentleman noticed me and liked what he saw. His name was Léonard Rwerekana, and he was already a successful businessman. We began winking at each other, on a few occasions. Still, in those days, the girl was not supposed to accept any kind of advances directly, so he asked my aunt to be the go-between and she pressed his case with my family. The gentleman walked an entire day in the sun to go visit my parents—who said that a man who had come on foot should not be made to cool his heels any longer. I got married when I was nineteen years old.

At the time, Nyamata was a straggling village of mud-brick houses with sheet-metal roofs. It wasn’t until 1974 that buildings of stone and concrete appeared. Léonard constructed his first house on our lot, then a warehouse on the main street, followed by some new stores. In 1976 he bought a van, an old, used van, but it was the first private vehicle. Then he opened the cabaret La Fraternité and some restaurants, developed the trade in beans and beverages, bought some fields and cattle. In 1980, with two new vans out on the road, he was the most important shipper in the area. Mounting jealousy was already coming between the Tutsi and Hutu business communities, because the Tutsis were prospering faster than the Hutus. One reason for this was that the Hutus coming from Gitarama didn’t know any of the customers in Nyamata. Another reason was that the Tutsis kept their clerks on for five or six years, until they were able to open their own little businesses, whereas the Hutus were always turning over their employees. But the most important thing was that the Tutsis worked with their inventory on hand and never borrowed money from anyone.

The day of the plane crash, it became difficult for Tutsis who lived in the center of town to leave. Lots of people sought protection within the solid wall around our house. Léonard had lived through several massacres in his youth, so he knew that this time the situation was out of control, and he advised the young people to sneak off up to Kayumba. But he himself no longer wanted to flee, and said that his legs had already run enough as it was.

On the morning of April 11, the first day of the massacres, the interahamwe showed up making a big commotion right outside our front gate. Léonard took the keys to go open it without making them wait, thinking to thus save the women and children. A soldier shot him down before he said a first word. The interahamwe poured into our courtyard, caught all the children they could, lined them up, laid them out on the ground, and began to butcher them. They even killed a Hutu boy, the son of a colonel, who had been playing there with some pals. I myself had managed to get around to the back of the house with my mother-in-law, and we lay down behind piles of tires. The killers didn’t finish the job, because they were in too much of a hurry to start looting. We could hear them getting into the cars, the vans, loading cases of Primus, fighting over the furniture and everything else, rummaging under the beds for money.

That evening, my mother-in-law left her hiding-place and sat down in front of the tires. Some young men saw her there and asked, “Mama, what are you doing here?” She replied, “I’m not doing anything anymore, since from now on I am alone.” They took her, they cut her, they carried away all that was left in the bedrooms and the parlor. They set a fire, and that’s why they forgot about me.

In the courtyard was a child who had not been killed. I leaned a ladder against the wall our house shared with the enclosure next door and I climbed up with the child to jump down into my neighbor Florient’s courtyard, which was empty. I hid the child in the woodshed and huddled inside the doghouse. On the third morning I heard footsteps, and recognizing my neighbor, I came out. “Marie-Louise,” he exclaimed, “they’re killing everyone in the town, your house has burned up, and you—you’re here? But now what is there I can do for you?” I said, “Florient, do this for me: kill me. But don’t reveal me to the interahamwe who will strip me and cut me to pieces.”

This Monsieur Florient was a Hutu. He was the military intelligence chief of the Bugesera, but he had built his house on our land, and before the war we had spoken kindly with one another, we had shared some good times, and our children had mingled freely in our two yards. So, he shut the child and me inside his house, gave us something to eat, and left. The next day he warned me: “Marie-Louise, they’re checking the corpses in town, they cannot find your face, and they’re looking for you. You must leave here, because if they catch you in my home, they will rob me in turn of my life.”

He took us at night to a Hutu woman he knew, who was hiding a small group of her Tutsi acquaintances. One day, the interahamwe came knocking on her door to search the house. The lady went to talk to them, came back, and asked, “Does anyone here have any money?” I gave her a wad of bills I had tucked into my pagne. After taking a small sum for herself, she returned to the interahamwe, who went away. Every day, the negotiation would begin again, and the lady was growing very nervous. Then one day Monsieur Florient brought another warning: “Marie-Louise, the young people in town, they want you too much, you must leave.” I said again to him, “Florient, you have the means, kill me, I want to die in a house. Do not let me fall into the hands of the interahamwe.” He said, “I will not kill my wife’s friend. If I find a vehicle, will you have money for payment?” I gave him another roll of bills I had, which he counted, saying, “This, this is something, they should accept it.” He came back and made an offer: “You’ll be put into a sack and taken into the forest. Then you’ll be on your own.” Then right away he said, “The interahamwe pillaged your house, the soldiers will go off with the money, and I who am saving you, I will come out of it with nothing: Is that really proper?” So then I told him, “Florient, I have two villas in Kigali: take them. The big store on the street, I leave it to you. I will sign papers procuring all this for you. But I want you to go with me toward Burundi.”

We left, with me lying down in the military van between the driver and Florient. First I stayed in his house at the military camp in Gako. I was locked in a room. While everyone was sleeping, someone would bring me food. I had only one pagne to wear. That lasted for weeks, I no longer remember how long. One night, a friend of Florient’s arrived with news. “The inkotanyi are coming in fast, we’ll be evacuating the barracks. Keeping you has become too prickly, I have to take you away.” He had me climb into a truck that was delivering sacks to the front. We drove off—all roadblocks opened at our passage—and into a dark forest, where the driver stopped beneath the trees. I was shaking and told him, “Well, I have nothing left. It’s my turn to die. At least if it’s quick, all right.” He replied, “Marie-Louise, I’m not going to kill you, because I work for Florient. Make your way straight ahead, don’t ever stop. At the end of the forest, you will place your hand on the barrier at our border with Burundi, and deliverance.” I trudged along, I fell, I crawled on my hands and knees. When I reached the border crossing, I heard voices calling in the darkness, and I fell asleep.

Later, a Burundian associate of my husband’s came to get me in a van at a refugee camp. When he saw me, he did not recognize me. He did not even want to believe that I was Léonard’s wife. I had lost forty-four pounds, I was wearing a pagne made from sacking, I had swollen feet and hair crawling with lice.

Monsieur Florient is now awaiting trial in the penitentiary at Rilima. He was an officer. He left every morning and returned at night with stories of how the killings were going in the town. I saw, in the corridor, piles of new axes and machetes. He spent my money, he looted my merchandise. In spite of that, never will I go to accuse him of anything in a courtroom, because when everyone thought only of killing, he saved one life.

I came back to Nyamata at the end of the genocide, in July. No one left in my family in Mugesera, no family alive in Nyamata, the neighbors killed, the warehouse pillaged, the trucks stolen. I had lost everything; life meant nothing to me. Nyamata was desolate, because all the roofs, all the doors and windows had been removed. But above all it was time itself that seemed broken in the town, as if time had stopped forever—or on the contrary had slipped away much too quickly while we were gone. I mean that we no longer knew when the whole business had begun, how many days and nights it had all lasted, what season we were in, and to tell the truth we just didn’t care. The children would go off into the thickets to catch chickens; we began to eat a little meat, we set to making repairs, tried to settle back into at least a few old habits. From then on we concentrated on the day at hand, caught up in searching for groups of friends with whom we could spend the night, so we wouldn’t die all alone in a nightmare.

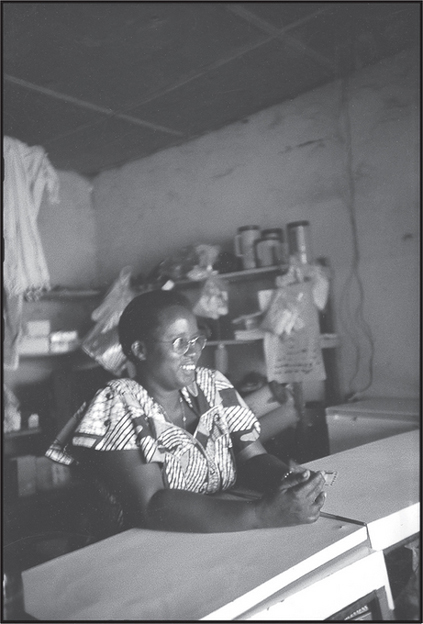

One morning, some friends brought me money and said, “Marie-Louise, take this. You’re good at bargaining, and we aren’t. You must take up business again.” I had a door put on this little shop; the trade came back, but the hope was gone. In the old days, prosperity held out its arms to me. Léonard and I, we went from one project to the next, our plans did well, we were loved and respected. Now I see all life with a somber eye, watching out everywhere for dangers large and small. I have lost the one who loved me, and can find no one left to help me bear up.

In the shop, customers tell me how they survived. In the evening, I hear acquaintances discussing the massacres. And I still don’t understand a thing about any of it. With the Hutus, we shared and shared alike, attended christenings and marriages—and then suddenly they went on a rampage like wild beasts. I don’t believe in the jealousy explanation, because envy has never driven anyone to lay children in a row in a courtyard and crush them with clubs. I don’t believe in that talk about beauty and a feeling of inferiority. In the hills, Tutsi and Hutu women alike were muddied and worn out by the fields; in the town, Tutsi and Hutu children were equally smiling and lovely to see.

The Hutus had the good fortune to monopolize all the choice state jobs and favors, they reaped fine harvests because they were excellent farmers, and they opened profitable businesses, at least selling retail. We shook hands cordially over deals we struck, we lent them money, and then, they decided to hack us to pieces.

They wanted to wipe us out so much that they became obsessed with burning our photo albums during the looting, so that the dead would no longer even have a chance to have existed. To be safer, they tried to kill people and their memories, and in any case to kill the memories when they couldn’t catch the people. They worked for our extermination and to erase all signs of that work, so to speak. Today, many survivors no longer possess one single little photo of their mama, their children, their baptism or marriage, a picture that could have helped them smooth a little sweetness over the pain of their loss.

Me, I see that the hatred in genocide springs solely from belonging to an ethnic group. Not from anything else, such as feelings of fear or frustration or the like. But the source of this hatred is still quite beyond to me. The why of hatred and genocide must not be asked of the survivors, it’s too hard for them to answer. It’s even too delicate a matter, they must be left to talk it over among themselves. The Hutus are the ones to ask.

Sometimes, Hutu women come back to see me, looking for work in the fields. I talk with them, I try to ask them why they wanted to kill us without ever complaining at all beforehand. But they’re not having any of it. They keep saying they didn’t do anything, they didn’t see a thing, their men weren’t interahamwe, and the authorities are to blame for what happened. They say our neighbors were forced to cut by the interahamwe, or else they would have been killed instead, and they leave it at that. I tell myself, These Hutus have killed without wavering and now they are trying to get out of discussing the truth, that’s not right. Reason why I’m not sure that it can’t happen all over again one day.

Everyone came out of the genocide at great cost: the Tutsis, the Hutus, the survivors, the interahamwe, the tradespeople, the farmers, the families, the children, all Rwandans. Maybe even the foreigners and the Whites who refused to see what was happening and took pity after the fact.

I think, moreover, that foreigners usually show pity that is all too much the same for different people who have not suffered the same misfortunes, as if the pity were more important than the misfortune. I also believe that if foreigners looked too closely at what we suffered during the genocide, they would not be able to handle their pity. Perhaps that’s why they look from so far away. But that seems like the past.

It’s more important that life has been shattered here, that wealth is spoiled, that no one pays attention to neighbors anymore, that people turn sad or nasty over trifles, that no one takes kindness seriously in the old way, that men are overwhelmed and women discouraged. And this is most disturbing.

Among ourselves, we never tire of talking about this post-genocide situation. We tell one another about certain moments, exchange explanations, tease one another, and if someone grows angry, we poke gentle fun to bring this person back to us. But showing our hearts to a stranger, talking about how we feel, laying bare our feelings as survivors, that shocks us beyond measure. When the exchange of words becomes too blunt, as in this moment with you, one must come to a full stop.