At this point in the book, the reader might wonder at reading only the stories of survivors. In Nyamata, moreover, the mayor, the chief prosecutor, some teachers back from exile, former prisoners from Rilima, Hutu farmers—guilty or innocent, bystanders or heroes—and some survivors themselves did suggest that I seek out other kinds of witnesses. The reason for my refusal is simple.

Early in the 1990s, after the first military successes of a Tutsi rebellion based in Uganda, a majority of the political class, the army, and the Hutu intelligentsia in Rwanda conceived a plan to exterminate the Tutsi population and certain important Hutu democrats. Beginning on April 7, 1994, for four to fourteen weeks, depending on the region, an astoundingly massive segment of the Hutu population grabbed machetes—whether they wanted to or not—and started killing. All foreigners, including humanitarian officials and civilian and military professional aid workers, had been sent to safety. Rare indeed, and appalled by the events, were the journalists who ventured out into the country, only to be largely ignored on their return.

After May, this genocide was followed by several telegenic episodes: a Dantean exodus of about two million Hutus, shepherded by the interahamwe militias, all fleeing reprisals, and the simultaneous conquest of the country by the rebel troops of the RPF, who had invaded from the Ugandan bush. Then in November 1996, two and a half years later, came the sudden and unexpected return of Hutu refugees, provoked by the strategic, vengeful, and quite murderous raids of the Tutsi RPF troops on the refugee camps, raids that even penetrated deep into the Congolese forests of Kivu.

There were very few foreign journalists in Rwanda during the Tutsi genocide in the spring of 1994, but a horde of them arrived to follow the Hutu refugee columns to the Congolese border that summer. This imbalance of information; the ambiguous motives behind the refugees’ flight; the dramatic aspects of those long, exhausting marches; and the hard line taken by the new leaders in Kigali all created confusion in the attitude of the West, which practically forgot about the survivors of the genocide clinging miserably to life out in the bush, and focused exclusively on the Hutu “victims” escaping along the roads to the camps in Congo.

On a trip to Rwanda during this exodus, I was struck by how withdrawn the survivors seemed in the accounts I was hearing. On a second trip three years later, in Nyamata, their mutism astonished me even more. The silence and isolation of the survivors, on their hills, were baffling. As I noted in my introduction, I recalled that only after a long time, when countless works by others on the Holocaust had already appeared, had the survivors of the Nazi concentration camps been willing and able to be heard and read, and I remembered how essential the survivors’ stories had been for any attempt to understand that genocide. During the first discussions with Sylvie Umubyeyi, and then Jeannette Ayinkamiye and others brought forward by Sylvie, I understood immediately the importance of listening to survivors.

My stay in Nyamata took place over several months, interrupted by periods of reflection in Paris, where I worked on the interviews and my notes and prepared new questions for my informants. A room in Édith’s house awaited me in Nyamata, along with an all-terrain vehicle rented from one of the beer merchants, Monsieur Chicago, and a tape recorder. Awakening at dawn to the shouts of a band of kids, morning appointment with Innocent or Sylvie, expedition into the bush to visit someone. Noon break, and another foray out to the homesteads. Late afternoons free—for playing with the kids or transcribing the tapes, word for word, for the interesting conversations and the pleasant music of the voices. The evenings: beers in a cabaret, chez Sylvie, or Marie-Louise, or Francine in Kibungo, or Marie in Kanzenze, to chat with friends. Weekends: more exclusively devoted to writing, listening to choir groups, and watching soccer matches. Unexpected encounters, a friendly visit from the photographer Raymond Depardon, or festivities sometimes altered this Spartan schedule.

I simply went looking for the stories of survivors, in the heart of this rolling countryside of marshes and banana groves. Some memories comprise hesitations or errors, pointed out by the survivors themselves, but these do not affect the truth of their narratives, so essential to any understanding of this genocide. That is why there are no statements from political or judicial notables in Nyamata or Kigali, or testimony from former interahamwe leaders or killers interviewed in the Rilima Penitentiary or abroad.14 For the same reason, I have not presented the viewpoints of any Hutu rebels or foreign protagonists in this drama.

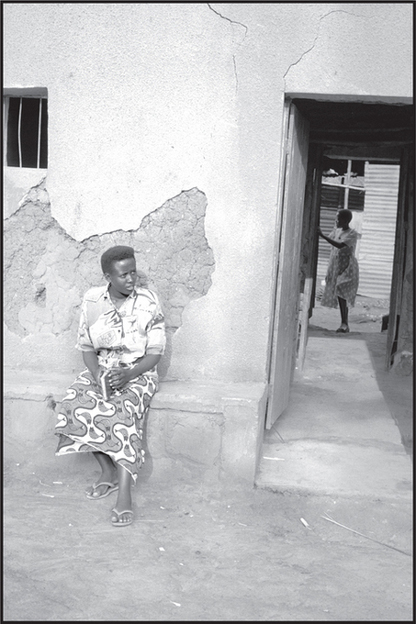

After that clarification, we now return to a path through a eucalyptus forest near N’tarama, accompanied by the trilling of the inyombya, that faithful forest companion with the forked tail of trailing blue feathers. We walk up a steep path that plunges into a half-wild banana grove; an exuberant bunch of kids erupts from behind a hedge. In a courtyard, a young woman in a field pagne is resting, leaning back against the wall of the house, her legs outstretched, a baby asleep on her lap. Her name is Berthe Mwanankabandi.

She offers water from a large jug. Like others, she is quite surprised to find that foreigners can be interested in her story and the genocide; she explains, like others, that she no longer believes in the value of bearing witness, but she expresses no wariness, quite the contrary. She agrees immediately to talk, all morning long, in a soft voice.

Like many of the women who live nearby, she never complains, never raises her voice, shows no bitterness or hatred, conceals any distrust she might feel for a white man, and restrains, through silences, any feelings of sadness or grief. When the time comes that afternoon to go work in the fields, she offers to continue her narrative later on. The following week—and one, two, six months later—she is still as concise as ever because, she explains, she is thus compelled to clarify some of her thoughts, out loud, for herself.