The steep clay path up to Claudine Kayitesi’s house plunges into the jumble of a banana grove and emerges before a flowering hedge. Her little house is of “non-durable” construction. In the Bugesera, dwellings are classified as non-durable, semi-durable, and durable depending on the construction of their walls—in other words, respectively, built from dried mud plastered on an armature of tree trunks, sun-dried bricks of mud mixed with straw and covered with pebble-dash or cement, or fired brick or cinder blocks. The roofs are usually mismatched sheets of corrugated metal, anchored by stones, or new metal roofing screwed down in overlapping sheets. There are some deep fissures in the walls of Claudine’s house, which her father built at least ten years ago, but unlike the neighboring house of her friend Berthe, Claudine’s doesn’t flood in the heavy downpours of the rainy season.

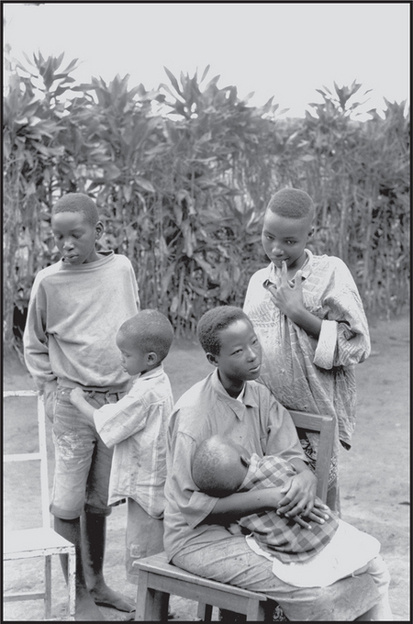

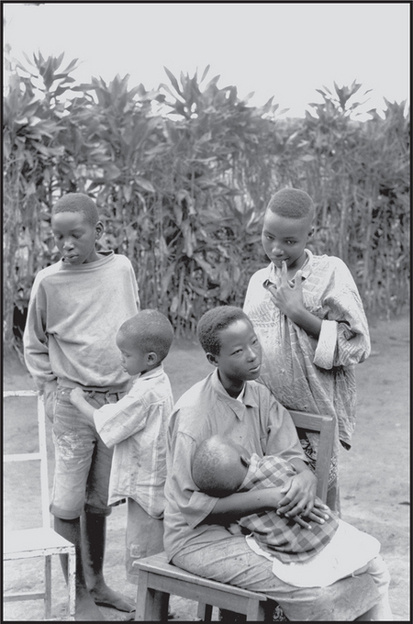

The first room is whitewashed, furnished with a low table and two chairs, and decorated with several bouquets of freshly picked flowers. This is where the family waits out any rainstorms. A panel of cloth divides the main area from a back room containing two plank beds. On a table sit a Bible, a communion crown of artificial flowers displayed in a basket, a charcoal-heated iron, and a sewing kit. This is the room of Claudine and Eugénie, her younger sister, who is helping her raise the children. On the right, a small, windowless storeroom holds sacks of beans, bags of salt and rice, a jug, and a bar of soap. There’s no sign of any candy or cookies. A travel bag full of clothes serves as a closet. The storeroom opens onto another bedroom with a mattress set on a platform shaped from the earthen floor itself. Here sleep the children: Jean-Petit, Joséphine, and thin little Nadine, a few months old.

No picture, no calendar or old poster decorates the walls as in Berthe’s or Jeannette’s house. Like the courtyard, the dirt floor is meticulously clean, thanks to a broom of leaves.

Outside, a superb settee of rustic woodwork and a bench are set along the wall. That’s where everyone chats when it’s not raining. The yard, round and spacious, is protected by a euphorbia hedge on which laundry and cloths are laid out to dry. In the shade of avocado trees, a square of greenery framed by flowerbeds and overhung by fragrant yellow bushes welcomes the evening gatherings. At the far end of the yard, a lattice-work of branches serves as shelves for a collection of pots, cups, and thermoses donated by humanitarian associations, as well as the buckets everyone uses while bathing to rinse one another off. The kitchen is in a terre-tôle hut too small to stand up in. Beans and bananas, the staples of both meals today, are cooking in an enormous pan over a wood fire. Tomorrow it will be beans and manioc, and the day after that, beans and corn. To Rwandans, a day without beans is no day at all.

The pen for the cow and calf, next to the kitchen, is constructed from thick branches stuck into the ground. The cow is scrawny, because after they get back from school, the children don’t have time to take her out to graze her fill. She produces little milk. Without at least four or five cows, it isn’t profitable to hire a young herd boy. Claudine explains that she can’t risk slipping her cow into a cattleman’s herd because in case of an escapade in someone’s field, she could not pay for the damage. The calf is no more chubby than its mother, but he’s lively. Two or three hens peck peevishly at one another on the dung heap; their chicks have a hard time surviving the feral cats. Behind the kitchen, at the edge of the banana grove, is the terre-tôle outhouse.

The closest houses belong to Berthe and, three hundred yards farther down the path, to Gilbert and Rodrigue, two teenage brothers who survived together in the marshes. The spring is a little over six hundred yards from Claudine’s house.

At sunset, the family gathers around a kerosene lamp concocted from a metal flask and a twist of cotton. From dawn to dusk, the house is cheered by an extraordinary concert of bird-song, by turns playful and languorous. Still, Claudine dreams of a radio or even a cassette player to help pass the long evening hours. She also dreams of a bicycle that would allow her to carry her shopping and water cans up from N’tarama, take her stems of bananas down to the market, and above all go more often to Nyamata, to visit people and have some fun.

Neither the drought that sears her banana plants, nor the cares of her large family, nor the difficulties of her “man’s work” ever draw the slightest complaint from Claudine or dampen her winning personality.