Convertible Bond Arbitrage

We predict and analyze the price relationships which exist between convertible securities … and their common stock. This allows us to forecast future price relationships and profits. We do not need to predict prices of individual securities in order to win.

—Thorp and Kassouf (1967)

15.1. WHAT IS A CONVERTIBLE BOND

A convertible bond is a corporate bond that can be converted into stock. Hence, a convertible bond is effectively a straight bond plus a warrant, that is, a call option to buy a newly issued share at a fixed price. A convertible bond has several important characteristics: Its par value is naturally the amount the owner will receive at maturity (if the bond has not been converted or called before then), and the coupon is the interest payments along the way. The conversion ratio is the number of stocks received upon conversion for each convertible bond. The conversion price is the nominal price per share (in terms of the bond’s par value) at which conversion takes place. Hence, the following relation clearly holds:

![]()

The so-called parity conversion value is the value of the convertible bond if it is converted immediately:

![]()

Many convertible bonds are callable, and some convertibles also have other option features. If a convertible bond is callable, then the issuer can redeem the bond before maturity (that is, pay the par value and stop paying coupons), subject to certain restrictions. A typical restriction is a call protection, meaning that the bond cannot be called for a certain time period.

Convertible bonds have been issued at least since the 1800s, among other things to finance railroads in the United States in the early days. Today, convertible bonds are often issued by smaller companies with a significant need for cash. Firms issue convertible bonds for a variety of reasons: Convertible bonds have lower financing cost (i.e., lower coupons) than straight debt because the buyers also receive the convertibility option. While convertible bonds dilute the equity, convertibles do so less than actual equity issues (e.g., the earnings per share is less diluted). Furthermore, it is possible to sell convertible bonds quickly as hedge funds and other arbitrageurs can hedge convertible bonds better than straight bonds. Convertible bonds are usually sold via an underwriting process, which can take as little as one day. The bonds are often sold as so-called 144a securities, meaning that they are yet to be registered with the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC). In this case, the convertible bonds can only be traded among qualified institutional buyers (QIBs), so they are especially illiquid until they are registered. When the bonds get registered (often after 3 to 6 months), then they can be sold in the public market. Because of a liquidity risk premium and adverse selection, convertible bonds are reportedly sold at an initial average discount (similar to the average initial public offering (IPO) underpricing of equities). Hence, part of the profit from convertible bond arbitrage comes from participating in the primary market and being active enough to secure allocations of bonds in oversubscribed issues.

15.2. THE LIFE OF A CONVERTIBLE BOND ARBITRAGE TRADE

Convertible bond arbitrage has been known almost as long as convertible bonds. Weinstein gave a description of a simple convertible bond arbitrage trade in his 1931 book, Arbitrage in Securities. Thorp and Kassouf developed the trade significantly in their book from 1967, Beat the Market, foreshadowing the Black–Scholes–Merton formula for option pricing.

At a high level, the trade is simple: buy a cheap convertible bond and hedge it by shorting the stock. Form a whole portfolio of such positions, and possibly overlay hedges for interest rate and credit risk. The trick is knowing whether a convertible bond is cheap and determining the appropriate hedge—and here is where the option pricing techniques come in handy.

Interestingly, convertible arbitrage tends to be one-sided, that is, the trade is usually to buy the convertible bond and short the stock. However, if the convertible bond is overpriced, hedge funds sometimes reverse the trade and short the convertible bond while buying the stock. The reason that the trade tends to be long on the convertible bond is that convertibles have historically been cheap, perhaps as compensation for liquidity risk.

Indeed, the cheapness of convertible bonds is at an efficiently inefficient level that reflects the supply and demand for liquidity: Convertible bonds are issued by firms who have a need for quickly raising cash and they are mostly bought by leveraged convertible arbitrage hedge funds. When the supply of convertible bonds is large relative to hedge funds’ capital and access to leverage, then the cheapness increases. For instance, when convertible bond hedge funds face large redemptions or when their bankers pull financing, then convertible bonds become very cheap and illiquid.

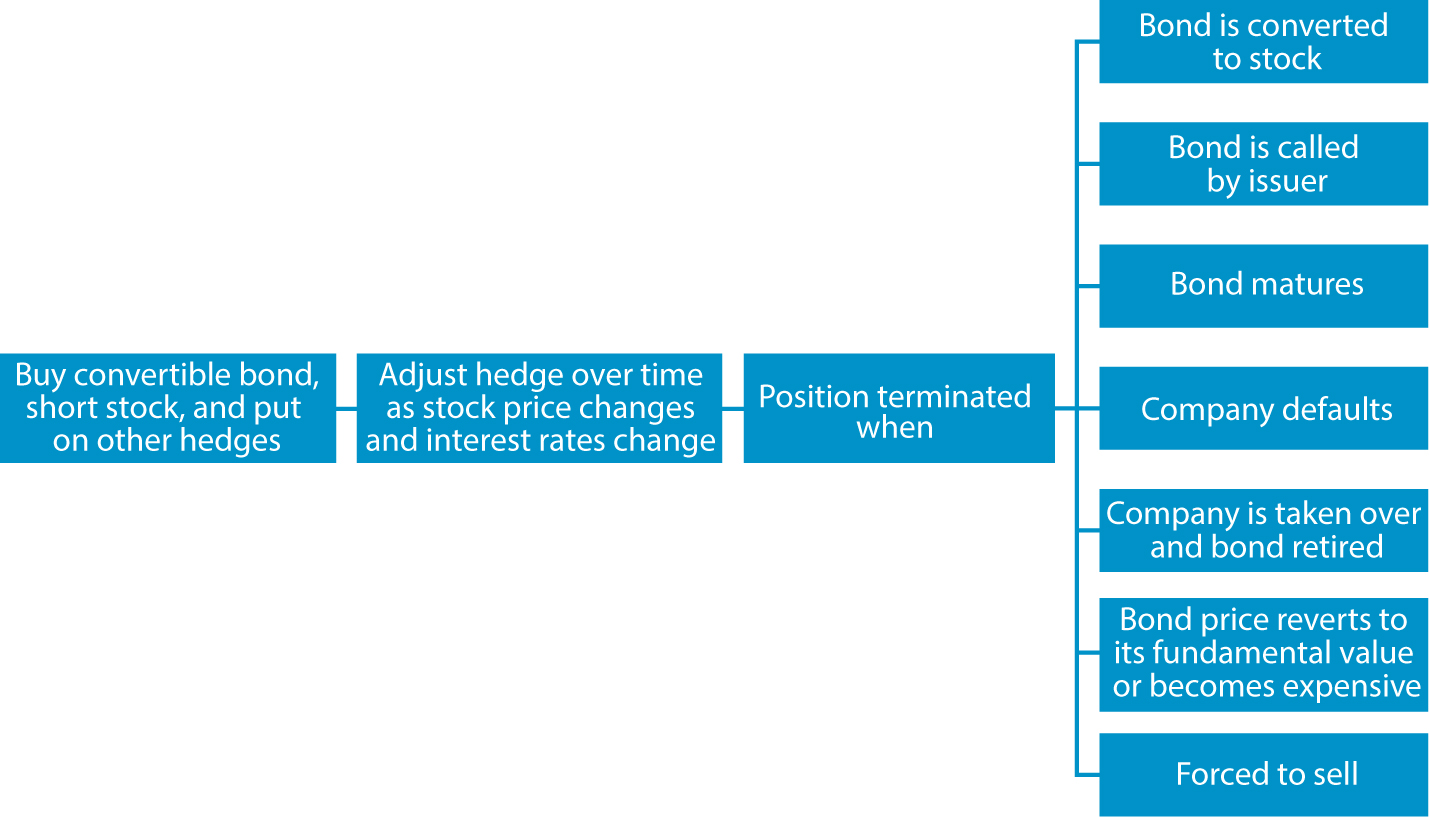

Figure 15.1 illustrates the life of a trade. The trader first acquires a long position in the convertible bond by buying it at a discount in the primary market or finding a cheap convertible in the secondary market. The trader then hedges his convertible bond by shorting the underlying common stock. The trader may refine the hedge by shorting a straight bond or by trading options, but such hedges are often very expensive, making it more economical to diversify away the idiosyncratic credit risk and hedge overall credit and interest-rate exposures at the portfolio level.

Over time, the convertible arbitrage trader will receive coupons on the convertible bond, compensate any dividends on the short stock position, and adjust the hedge as the stock price changes.

The trade can end in a number of different ways, as seen in figure 15.1: The convertible bond may be converted to stock. In this case, most of the shares are used to cover the short position in the hedge and the rest are sold. Conversion is typically the end of a successful trade (and I discuss below when conversion is optimal). The convertible bond may also simply mature or be called by the issuer. Other possible outcomes are that the company defaults or is taken over, and such events are usually negative for the convertible arbitrage trader. Finally, the trader might decide to sell his position in convertible bonds, either to take profit when the bond has richened sufficiently or because of forced selling due to margin calls.

Figure 15.1. The life of a convertible arbitrage trade.

15.3. VALUATION OF CONVERTIBLE BONDS

Convertible bonds can be valued using option pricing techniques. A simple method is to consider the value of a straight bond and then add the value of a call option computed using the Black–Scholes–Merton model. This method is not exact since it does not take into account that the conversion implies that the stock is bought for convertible bonds rather than cash, and the value of bonds varies over time. Furthermore, this method does not account for all the special features in the convertible bond’s indenture, such as the possible callability. Hence, most convertible bond pricing models are based on extensions of the basic Black–Scholes–Merton framework solved numerically using binomial option pricing techniques or partial differential equations. Said simply, such models construct a tree of all the possible ways that the stock price can evolve, compute the convertible bond value at the end of each branch of the tree, and then work backward in the tree to compute the current value.

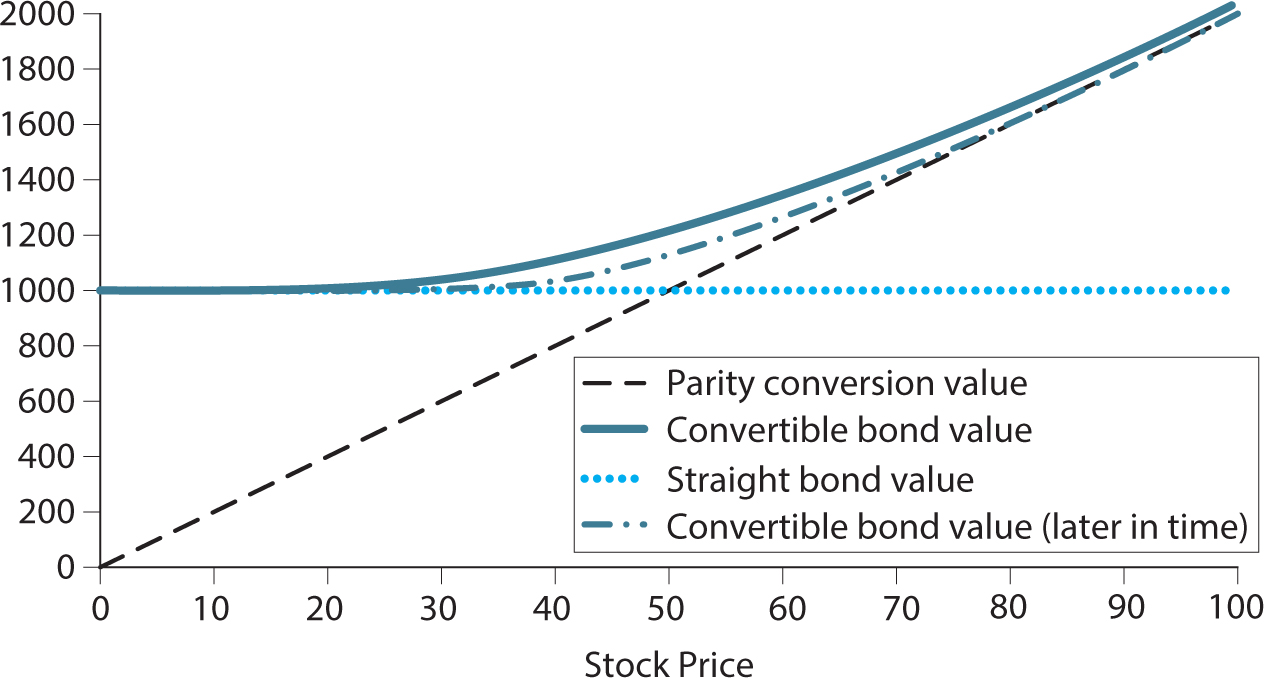

Rather than going through the details of this calculation (which is standard financial engineering by now), let us gain some intuition for how convertible bond values depend on stock prices, as seen in figure 15.2. The dotted line shows the value of a straight bond (i.e., a bond without the convertibility option). The value of a straight bond is independent of the stock price when we assume that there is no risk of default; hence, the dotted line is horizontal. The dashed line shows the parity conversion value, that is, the value of converting immediately. Naturally, the parity conversion value is linear in the stock price and the slope is the conversion ratio. When the convertible bond matures, its value is the upper envelope of these two lines: a hockey-stick shape with value 1,000 for stock prices between 0 and 50 and increasing value for higher stock prices. Indeed, for stock prices below 50, the owner of the convertible bond can choose not to convert and receive the value of the bond and, if the stock price is above 50, the owner can optimally convert.

Before maturity, the convertible bond value is given by the smooth curve (solid line), which is above the hockey stick due to option value. To understand why, suppose for instance that the stock price is 50. Clearly, the convertible bond is worth more than 1,000 since, if the stock price goes up, the convertible bond will be worth more than 1,000 and, if the stock price goes down, the bond will be worth 1,000. An average of 1,000 and something above 1,000 is above 1,000! How much above? That depends on how much time is left and the volatility of the stock.

Figure 15.2. How the value of a convertible bond depends on the stock price: the case of no default.

While figure 15.2 considered the example of a convertible bond issued by a firm with no risk of bankruptcy, figure 15.3 considers what happens if bankruptcy is a possibility. The top panel puts the value of the entire firm on the x-axis, rather than the stock price. The firm is assumed to have a total debt of 100 million, so bankruptcy occurs when the firm value drops below this level. Assuming that all bond holders have equal seniority (e.g., because the convertible bond is the only debt outstanding), we see that the value of an unconverted bond at maturity increases from 0 to the par value as the firm value increases from 0 to 100 million, and the straight bond value stays at this level for higher firm values. The risk of default is similar to being short a put option written on the value of the firm. The value of the convertible bond some time before maturity now has a more complex shape: concave for very low values of the firm (due to default risk) and convex for intermediate and high values (due to convertibility option value).

Panel B of figure 15.3 depicts the convertible bond value as a function of the stock price. The parity conversion value is the same as before, but now the value of straight debt is different: this figure plots the value of the straight debt reflecting default risk at some time before maturity (because the value at maturity is difficult to depict with the stock price on the x-axis). Again we see the convex/concave shape of the convertible bond value.

Figure 15.3. How the value of a convertible bond depends on the firm value and stock price.

Panel A. Convertible bond value vs. firm value.

Panel B. Convertible bond value vs. stock price.

15.4. HEDGING CONVERTIBLE BONDS

Computing the value of a convertible bond and its hedge ratio are closely intertwined. Indeed, the optimal hedge ratio captures the change in the value of the convertible bond per unit of change in the underlying stock.

The hedge ratio is the number of stocks that a market-neutral arbitrageur should short for every convertible bond, usually denoted by delta, Δ. The arbitrage trader needs to choose the hedge ratio so that the stock-price sensitivity of the hedge equals the stock-price sensitivity of convertible bond, as seen in figure 15.4.

Figure 15.4 shows the optimal hedge if the current stock price is 55. The dotted line is the tangency of the convertible bond value, and its slope is the hedge. The hedge ratio clearly depends on the stock price, so as the stock price moves around, the convertible bond arbitrageur needs to readjust the hedge. For very high stock prices, conversion becomes ever more certain and the hedge ratio approaches the conversion ratio. The hedge ratio drops for lower stock prices, but it can pick up for stock prices so low that credit risk becomes a serious concern.

15.5. WHEN TO CONVERT A CONVERTIBLE

A Wall Street saying holds that one should “never convert a convertible.” The reason is that it is usually better to keep the options open: Either convert later if the stock price keeps rising or receive the face value of the bond if the stock price falls. The reason that conversion should usually be postponed corresponds to the reasons for postponing the exercise of an American call option.1

There are, however, several important exceptions to this never-convert-before-maturity rule: First, if the stock is about to pay a dividend, then early conversion can be optimal. Indeed, converting the bond to stock before the dividend payment means that you receive the dividend. In contrast, failure to convert means that you will not receive the dividend and, furthermore, the stock price is expected to drop after the dividend date, reducing the value of the conversion option. Said differently, if money is about to leave the firm, you may protect your investment best by claiming part of this money and, to do so, you need to convert the bond to stock.

A second example where conversion may better protect the investment is an impending merger. If the merger makes the debt riskier and conversion is not possible in the merged company (e.g., because it is a private company), then early conversion is optimal.

Third, financial frictions can lead a convertible bond manager to convert the bond. For instance, if the stock has a high lending fee, it is expensive to short the stock. This leads to a constant drag on the hedged convertible bond position, similar to the drag of a stock that continually pays dividends. Therefore, it can be optimal to convert such convertible bonds.

Converting a deep-in-the-money convertible bond can also be optimal in light of funding costs. For such bonds, the cost of converting early is small (the bond will almost surely be converted eventually anyway since it is deep-in-the-money), and these small costs can be more than outweighed by reduced funding costs. Indeed, a convertible bond ties up capital that could otherwise be used for other trades, and it is associated with funding costs due to the financing spread, that is, the difference between the interest earned on the cash collateral supporting the short stock position and the interest rate paid on any leverage of the convertible bond. An alternative to converting a bond is selling it, but this may not be preferable, given the large transaction costs for convertible bonds and given that the potential buyers may face similar funding costs.

15.6. PROFITS AND LOSSES IN CONVERTIBLE ARBITRAGE

What Money Flows In and Out?

The convertible bond position generates income from the coupon paid by the bond. If the convertible bond is leveraged—which it is for most arbitrage traders—then interest payments must be made for the financing. Furthermore, the convertible bond trader must cover the cost of dividend payments on the short equity position as well as short-selling costs, especially for stocks that are “on special” (i.e., stocks with high demand for short-selling relative to the supply of lendable shares). In fact, companies with many outstanding convertible bonds are more likely to face high short-selling costs because of the demand to borrow the shares from owners of convertible bonds.

The primary driver of profit and loss, however, is changes in the prices of the stock and the convertible bonds. Stock price changes naturally feed into the convertible bond price, but, as discussed in detail below, these price moves are not perfectly offsetting. Convertible bond prices are also affected by changes in the volatility of the stock price and in the supply and demand for convertible bonds. The demand for convertible bonds is driven by flows to convertible bond hedge funds and mutual funds, risk appetite of these investors, and the financing environment, which affects convertible bond arbitrageurs’ ability to take on leveraged positions.

Gamma: Making Money from Ups and Downs

One of the surprising characteristics of a hedged convertible bond position is that it can profit both from stock price increases and drops. Indeed, when the stock price moves up, the convertible bond moves up by more than the stock hedge, leading to a profit. The convertible bond moves by more because it benefits both from the higher value of the stock and from a higher chance of converting. When the stock price moves down, the convertible bond suffers less than the stock hedge, also leading to profit. The convertible bond moves by less because its downside is limited due to its bond characteristics.

Figure 15.5 and table 15.1 illustrate an example in which the stock price first jumps up from 55 to 85 and then jumps back down to 55. The property of benefiting both from up and down moves is called convexity, which refers to the shape of the value of the convertible bond in figure 15.5—it “curves upward” relative to the dotted line for the hedge (a formal definition is given in the chapter on fixed-income arbitrage). This property is also called positive gamma, where gamma is the second derivative of the value of the convertible bond with respect to the price of the stock.

Figure 15.5. The profit and loss (P&L) of convertible bond arbitrage when the stock price increases and decreases.

Panel A: P&L of convertible bond arbitrage when the stock price increases.

Panel B: P&L of convertible bond arbitrage when the stock price decreases.

As seen in Panel A of figure 15.5, the convertible bond value increases by more than the stock hedge when the stock price goes from 55 to 85. Specifically, as seen in table 15.1, the convertible bond increases by $500.17, more than offsetting the increase in the hedge of 13.4 shares, $403.00. The difference, $97.17, is the profit on the hedged position.

TABLE 15.1. THE PROFIT AND LOSS (P&L) OF CONVERTIBLE BOND ARBITRAGE WHEN THE STOCK PRICE INCREASES AND DECREASES

P&L When Stock Price Moves from $55 to $85 |

| |

Long 1 convertible bond |

$500.17 | |

Short 13.4 shares |

–$403.00 | |

Total |

$97.17 | |

P&L When Stock Price Moves from $85 to $55 |

| |

Long 1 convertible bond |

–$500.17 | |

Short 18.6 shares |

$558.16 | |

Total |

$57.99 | |

P&L of Total Round Trip |

$155.16 | |

When the stock price drops back from 85 to 55, why isn’t the initial profit simply reversed? The initial profit would be reversed if the hedge had not been adjusted in the meantime, of course. It is the change in the hedge that makes the difference: With the stock price at 85, the initial hedge of 13.4 shares short is no longer appropriate. This is because the convertible bond is now more in-the-money, that is, more certain to be converted; it has therefore become more equity sensitive. Hence, the correct hedge has increased to 18.6 shares.

Given this new hedge, a drop in the stock price leads to a larger drop in the value of the hedge than the value of the convertible bond. Hence, the drop in the stock price leads to a profit of $57.99, as seen in table 15.1. Note from table 15.1 that the net profit/loss of the convertible bond itself is exactly zero from the round trip: the initial profit of $500.17 is exactly erased when the stock price drops back, for obvious reasons. The profit from the round trip trade comes from the asymmetry of the hedge.

So convertible bond arbitrage can make money from both ups and downs in the stock market—does this mean that the strategy can never lose money? Surely not. As we will see, the strategy can lose money in several ways. First of all, the position is not convex everywhere. As seen in figure 15.5, the value of the convertible bond bends down for low stock prices, a negative gamma coming from the default risk having the effect of a short put option. Hence, certain extreme negative stock price moves are often bad for convertible bonds. For example, the default of the firm can lead to losses for the convertible bond arbitrageur.

Time Decay: Losing Money for Nothing

We have seen that convertible bond arbitrage can profit both from ups and downs in the stock market, but another surprising effect is that the strategy loses from the lack of stock price moves. If time passes without stock price moves, then this is a loss to the convertible bond arbitrage trader!

Figure 15.6 illustrates this effect, called time decay (or theta, the sensitivity with respect to time). Recall that the convertible bond value is strictly above the parity conversion value and the value of a straight bond because of option value. Hence, when you buy a convertible bond, you are paying a premium for the potential to make money from ups and downs. This price premium is key to understanding time decay. As time passes, the future opportunities to make money from ups and downs diminish. Hence, the option value diminishes and the convertible bond price therefore shrinks toward the values of straight debt and parity conversion, as seen in figure 15.6. This shrinking option value is a loss to the convertible bond trader—i.e., time decay.

Hence, stock price ups and downs lead to profit, but losses arise when the clock is ticking without stock price moves. The total profit over the life of the trade depends on how many stock moves you get vs. how many stock price moves you implicitly paid for when you bought the convertible.

Vega: Hoping for Lots of Ups and Downs

Since the hedged convertible bond position profits from price moves up and down, a higher stock price volatility means that the convertible bond is more valuable. A higher perceived stock price volatility does not just imply higher future profits; rather, it raises the current price of the convertible bond given that the market is forward looking. Hence, increases in perceived stock price volatility tend to increase the price of convertibles, while drops in volatility have the opposite effect. The price sensitivity to volatility is called vega, so traders say that convertible bond arbitrage has positive vega since the convertible is long on an embedded call option.

Figure 15.6. The loss for convertible bond arbitrage caused by time decay.

The alpha of convertible bond arbitrage comes from buying convertible bonds that are cheap relative to their fundamental value. Convertible bonds have historically been sold at an average discount to the value of their components (bond + option) for several reasons.

First, many buyers of corporate securities shy away from convertible bonds or require a large return premium since convertible bonds require expertise to trade, have large transaction costs, face market liquidity risk (meaning transaction costs sometimes increase dramatically and dealers even stop making markets), are difficult and expensive to finance, and face funding liquidity risk (meaning that margin requirements can increase or financing can be withdrawn).

Second, issuers of convertible bonds are willing to accept a liquidity discount if they are in need of cash and can sell convertible bonds more quickly and at lower investment-banking fees than other sources of financing.

Hence, convertible bond arbitrage earns a liquidity risk premium for holding an asset with market and funding liquidity risks, providing financing for companies that might otherwise have difficulty borrowing.

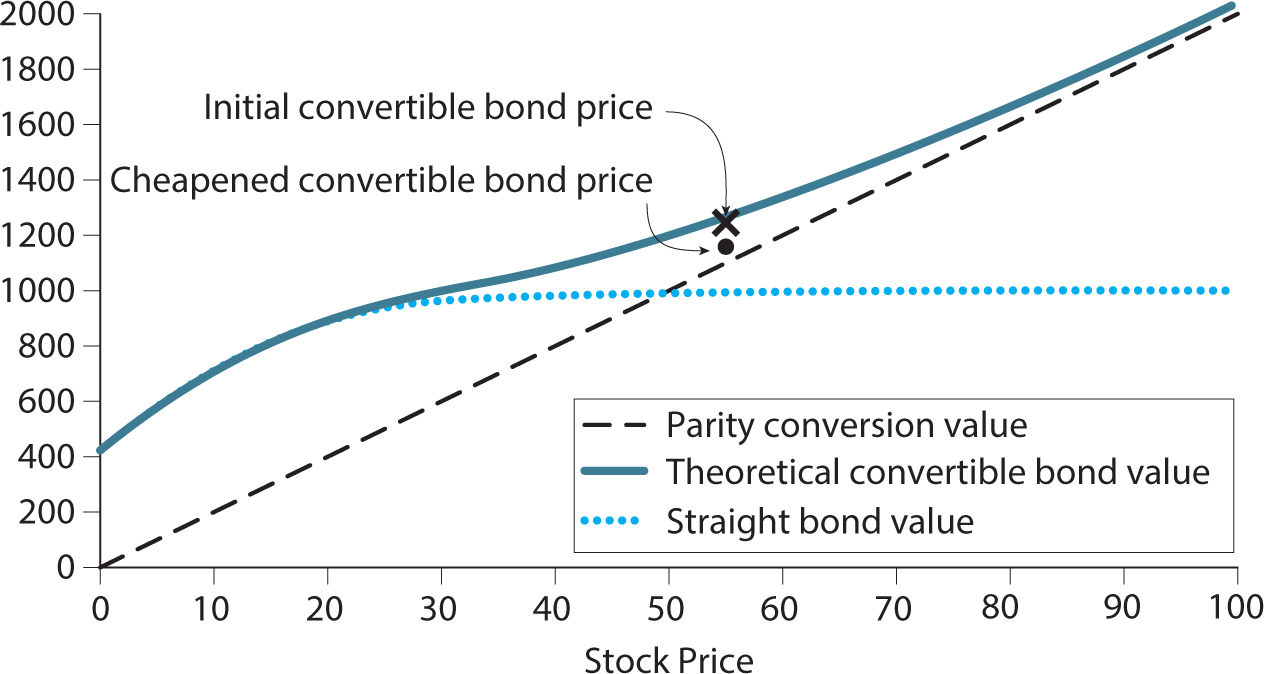

Figure 15.7. Cheapening of a convertible bond.

The liquidity discount of a convertible bond is illustrated in figure 15.7. The initial price of the convertible bond (indicated by the x in the graph) is below the theoretical value (the solid line). This discount in the price is the source of alpha in convertible bond arbitrage. In contrast, if the convertible bond were bought at its theoretical value, the alpha of the strategy would be zero, and paying a price above the theoretical value would be associated with negative alpha.

If convertible bond market conditions worsen (without a change in the stock price), then the convertible bond will cheapen further relative to the theoretical value, as seen in figure 15.7. This would lead to a loss for the arbitrageur but would set up higher expected profits in the future.

15.7. TYPES OF CONVERTIBLE BONDS

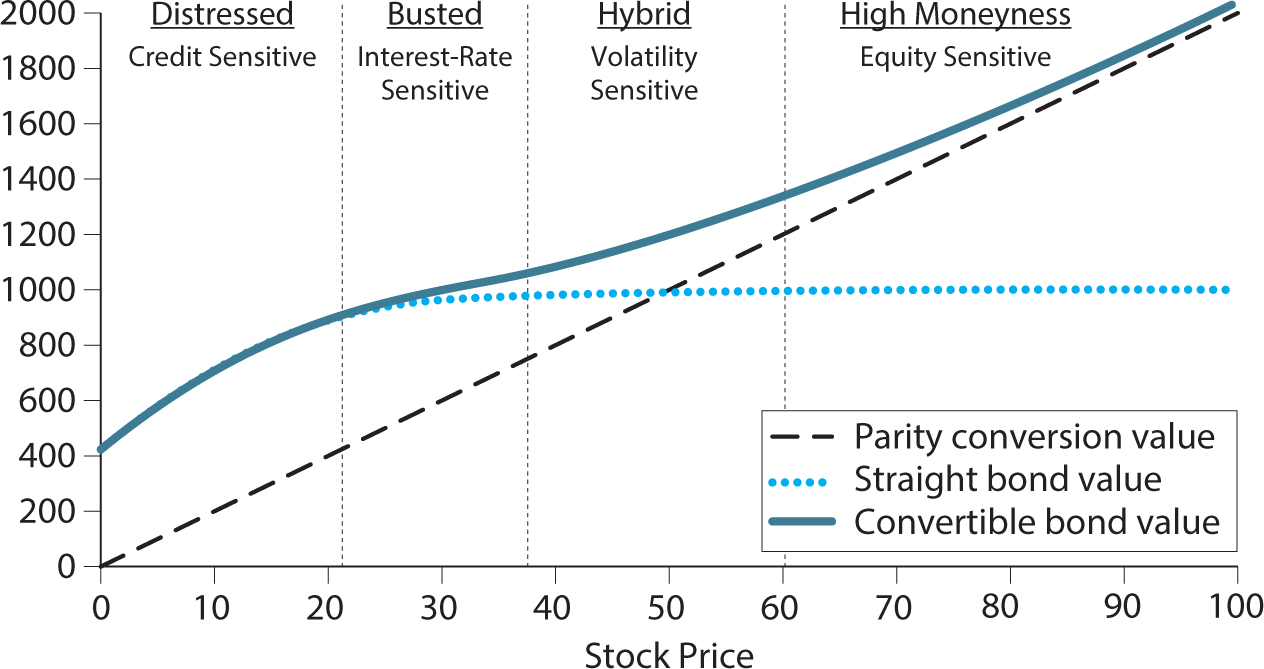

Convertible bonds are sometimes classified loosely into several categories, as illustrated in figure 15.8. Furthermore, some convertible bond managers specialize in a particular type of convertibles, whether it be distressed, busted, hybrid, or high-moneyness convertibles. Such specialization can increase a manager’s expertise, but it can also be associated with additional transaction costs if bonds are bought and sold as they move between categories.

High-moneyness convertible bonds are in-the-money and therefore highly equity sensitive. Some convertible arbitrage managers believe that such high-money convertibles offer the highest risk-adjusted returns, but these bonds also require the most leverage to generate significant risk and total return.

Hybrid convertible bonds are closer to being at-the-money and are therefore especially sensitive to equity volatility. Busted convertibles are out-of-the-money and therefore have little optionality, but the stock price is nevertheless not so low that credit risk plays as significant a role as it does for distressed convertibles.

Figure 15.8. Types of convertible bonds.

15.8. HEDGEABLE AND UNHEDGEABLE RISKS FOR A PORTFOLIO OF CONVERTIBLES

Market Risk, Interest-Rate Risk, and Credit Risk

The most obvious risk in owning a convertible bond portfolio is equity market risk, but the delta hedging discussed above largely takes care of this. Convertible bonds also face interest-rate risk since higher interest rates makes the bond’s fixed coupons less valuable. Interest-rate risk can be hedged by shorting bond futures, straight corporate bonds, Treasuries, or interest-rate swaps.

Furthermore, convertible bonds face credit risk. While the equity hedge partially protects against the risk of default, this hedge often does not fully cover the loss on the convertible bond in case of default. Each bond’s default risk can be hedged by buying credit default swap (CDS) protection (if CDSs are traded for that firm) or by selling straight corporate bonds. However, buying protection on all convertible bonds in a portfolio is expensive and associated with large transaction costs. Alternatively, a convertible arbitrage trader can make sure that her portfolio is well diversified, largely diversifying away idiosyncratic credit risk. Changes in marketwide credit risk can then be hedged with a credit default swap index such as CDX or iTraxx. Convertible bonds also face risks in connection with takeovers and other corporate events. Such event risk is difficult to hedge, but it can be diversified away to some extent.

Valuation and Liquidity Risk: Efficiently Inefficient Convertible Bond Prices

The major risks that cannot be hedged or diversified away are (1) a systematic cheapening of convertible bonds relative to their theoretical value, (2) funding liquidity risk, and (3) market liquidity risk. What is worse, these three risks are closely connected and often materialize at the same time. A cheapening of convertible bonds leads to losses for convertible bond traders, which creates funding problems. Such funding problems can lead to forced selling, and, as traders rush for the exit, market liquidity dries up, creating a downward spiral of prices and liquidity. Such liquidity events occurred in the convertible bond markets in 1998, 2005, and, most violently, in 2008.2

Figure 15.9. Available prime broker leverage for a large convertible bond arbitrage fund. Leverage is measured as the value of the long convertible bond positions relative to the net asset value.

Source: Mitchell and Pulvino (2012).

Figure 15.9 shows the available leverage for a large convertible arbitrage hedge fund from its prime brokers, June 2008 to December 2010. We see that convertible bonds with high moneyness can be leveraged more than low-moneyness bonds because their unhedgeable risk is smaller. More importantly, the available leverage fell significantly (that is, margin requirements went way up) during the global financial crisis when Lehman Brothers failed and most brokers were in trouble. In fact, this figure understates the magnitude of the funding crisis in the convertible bond markets as margin requirements went up even more for many smaller hedge funds and some simply had their financing pulled and were forced to liquidate.

The prices of convertible bonds fell dramatically as a result. An extreme example of the price drop of convertible bonds was that convertible bonds sometimes even traded cheaper than comparable bonds without the convertibility option! Figure 15.10 shows the average and median difference in yield between convertible bonds and straight bonds issued by the same company. Specifically, the sample consists of 596 busted convertible bonds trading below par, with at least one year of remaining life and with straight debt outstanding with a similar maturity date. Even though the convertible bonds have been chosen to have low option value (since they are trading below par), they still have significant optionality and therefore convertible bonds should naturally have a lower yield than straight bonds. Normally, this is indeed the case, and figure 15.10 also shows a yield difference above 6% in the early time period. However, the liquidity crisis that hit the convertible bond market when Lehman Brothers failed was so severe that the yield difference collapsed to near zero and, in some instances, it even went negative! The market for convertible bonds was dominated by leveraged long–short hedge funds, which had severe liquidity problems due to the liquidity problems of their brokers, while the market for straight bonds was dominated by unleveraged long-only investors less affected by these events.

Figure 15.10. The yield difference between straight bonds and convertible bonds.

Source: Mitchell and Pulvino (2012).

A similar liquidity event happened in the convertible bond market in 1998 in connection with the collapse of the hedge fund LTCM. As seen in figure 15.11, the price of convertible bonds dropped significantly relative to their theoretical value and, as a result, convertible arbitrage initially suffered losses and earned high returns as the cheapness diminished.

Mergers, Takeovers, and Other Sources of Risk

Mergers, takeovers, special dividends, and corporate restructurings present risk for convertible bond owners as other stakeholders may extract value from the firm, the convertible may be redeemed and lose its option value, or the convertible may be adversely affected by the fine print of the contract.

A takeover can be both good and bad. If the convertible is in-the-money and the takeover bid makes the stock price jump up, then this typically leads to profits for the hedged convertible due to its convexity.

Figure 15.11. Price-to-theoretical value of convertible bonds, and return of convertible bond hedge funds.

Source: Mitchell, Pedersen, and Pulvino (2007).

However, consider the case of a takeover below the conversion price so that the convertible bond remains out-of-the-money. If the convertible bond is redeemed or loses its option value in the merged company (e.g., if it is a private company with a worse credit), then the convertible bond price will fall to the par value or below. At the same time, the stock price will increase on the takeover announcement, hurting the short stock hedge. Hence, in this situation, the convertible bond arbitrageur may lose both on the long convertible bond and on the short stock.

To limit this takeover risk, most convertible bonds are now issued with takeover protection clauses that allow the convertible bond owner to put the bond back to the issuer at par value in the event of a takeover and possibly to give the convertible bond owner the right to additional shares under certain conditions.

15.9. INTERVIEW WITH KEN GRIFFIN OF CITADEL

Kenneth C. Griffin is the founder and chief executive officer of Citadel, one of the world’s largest alternative asset managers and securities dealers. Griffin received a bachelor’s degree from Harvard University while starting and running two hedge funds at the same time. Shortly after he graduated, he founded Citadel in 1990, and his youthful success quickly made him a legend. He started with a focus on convertible bond arbitrage, and Citadel now includes a number of hedge funds engaged in several alternative investment strategies.

LHP: I would like to first ask you about the legend of your dorm room trading and the beginning of your trading career.

KG: I began trading my freshman year at Harvard. There was an article in Forbes about why Home Shopping Network was extremely overvalued. After reading the article, I bought puts on the stock. Shortly thereafter, the stock plummeted and I made a few thousand dollars. But when I exited the position, the market maker paid me the intrinsic value less a quarter of a point for the options.

LHP: So that got you thinking about market making, transaction costs, and arbitrage?

KG: Yes, I realized that on a risk–reward basis, that market maker’s transaction was far better than my investment. I had great appreciation for the fact that I was quite lucky, whereas the $50.00 the market maker earned was basically risk free. That piqued my interest to understand what investments sophisticated market participants engage in. I started to view the markets through the lens of relative value trading rather than just directional positioning.

LHP: How did you figure out that you could make money trading convertible bonds, and how did you start trading?

KG: In my time at college, I came across an S&P bond guide at Baker Library at Harvard Business School. In the back of the S&P bond guide, they list convertible bonds. For each bond they provide the coupon, the conversion ratio, the conversion value—all the salient terms of the instrument. Based on the market prices in that book, there appeared to be some bonds that were mispriced. I made it my mission to educate myself on these instruments and to understand the pricing and trading of convertibles.

LHP: Was the insight just based on some back of the envelope calculations, or did you need to already appreciate something like the Black–Scholes Formula or the binomial option pricing model at that time?

KG: Back of the envelope, some common sense, and a bit of naïveté as to the dynamics around why these mispricings might exist. Many mispricings were driven by the inability to borrow the underlying common stock and therefore the convertible bond traded close to conversion value because the arbitrage was difficult. Nonetheless, I didn’t understand these dynamics at the moment. As I looked at the S&P guide at the Baker Library, it caught my interest.

LHP: Then you started reaching out to more people and actually started trading on these things.

KG: I dove into understanding the convertible market and came across a number of articles and books written over the years on convertible bond arbitrage. I put together a small partnership with a friend to manage money in the space. We raised about $250,000 from friends and family to deploy this strategy. It was actually $265,000—strange the numbers you remember. That was in September of 1987.

LHP: That was a unique time—the following month was the crash.

KG: Exactly. And not fully understanding how these bonds would behave in a downward market, my hedging strategy was generally to be short in extra margin of stock to compensate for the uncertainty in the bear market case.

LHP: Good move.

KG: Yes, that helped to preserve capital in the crash of ’87. The crash of ’87 created a number of dislocations in the marketplace that I was able to capitalize on with respect to my small fund and, on the back of that, I raised a second fund. I was managing just over a million dollars in college between these two funds.

LHP: Help me visualize you in college running these funds—how did you actually do it?

KG: I had a satellite dish on top of my dorm. I set up a phone and fax machine. I arranged to pull a cable down an unused elevator shaft, up to the roof of the building, and had a satellite dish on the roof to get real-time streaming stock prices. I had to pull some wires down the hall, but no one seemed to mind.

LHP: How did you do the trades?

KG: I traded between classes. I used a lot of pay phones on campus.

LHP: Were those to adjust your hedge or to put on new convertible positions or to take convertible positions off?

KG: All of the above. There would be a couple of trades a week to adjust the stock hedges and then other trades to buy and sell convertibles.

LHP: How did you decide which bonds to buy and when to buy? Did you have a computer, and did you have a valuation model?

KG: Back then all the decisions were made using paper and pencil and trying to approximate where I thought the bonds should trade based upon cash flow differentials, creditworthiness, and the inherent call protection of the bond. I started to piece together simplistic models based upon the principles of Black–Scholes. The real work in modeling convertibles hit its stride around 1991, two years after I graduated.

LHP: In the early days, how did you even keep track of your portfolio of bonds? Was it you had it in your head, or you had it in a notebook, or you had it in a computer?

KG: I organized it in my head. There weren’t that many positions, and I assure you this was the greatest interest of my day! I could tell you conversion ratios to coupons on pretty much any of the positions at that time. I had spreadsheets and papers everywhere! When I was in a class, I’d have my HP 12C calculator, a scrap of paper, and think through the information in my head, and I’d make decisions.

LHP: How did you find time for all this? You still had to do your classes.

KG: I had a less than perfect attendance record.

LHP: What were the challenges and advantages in running a small fund?

KG: One of my advantages at that time was that I wasn’t managing a lot of money. What you need to think about when you’re in that position is not how much you have, but how to make the most of what you have. I realized that being small, I could borrow quantities of shares that were inconsequential to a large player—even though they were quite consequential to me! So those very convertibles that were mispriced because it was hard to borrow the stock represented the majority of my portfolio at the time.

LHP: So how did you manage to borrow the stock for shorting?

KG: I would do things like open accounts at Charles Schwab. They would have the stock in their retail accounts, and I could carry the longs and the shorts there. None of the large hedge funds were using Charles Schwab as a prime broker back in the late ’80s or early ’90s.

LHP: So you developed an edge in convertibles for firms with hard-to-short stocks?

KG: Yes. I would call two or three dealers, and the dealers would call me with incoming securities that they thought might be of interest to me. I built a reputation as the go-to person for names related to hard-to-borrow stocks.

LHP: Being part of the flow is very useful in convertible bond arbitrage, but it seems amazing that dealers would be calling a college kid.

KG: Yes, I suppose you’re right. But you know, many trades in the convertible market back then were just a few hundred thousand dollars. There were a lot of small trades. So a hundred thousand dollar trade, I could do that, and so I’d be on the list for that phone call. Today we’ll trade 15 or 20 million bonds on the wire, but back then the market was far smaller with fewer players. And there was a large retail component to the order flow that swept through the marketplace. A dealer might have an incoming retail order in a name like Chock Full o’Nuts, the coffee company. They knew that was a stock that I was routinely able to borrow and that I’d have an interest in trading with them.

LHP: One of your first motivations was thinking about who earns the transaction costs, but you probably also had to pay large spreads on the convertible bonds, especially being a small hedge fund?

KG: Given that I was trading from my dorm room, I was a bit of a novelty on Wall Street to say the least. Contrary to conventional wisdom on how Wall Street treats people, I was treated extraordinarily well by people in the industry who would do business with me on very fair terms because they were good people and wanted to help me out. A number of people who traded with me in college are still friends today.

LHP: How did you evolve from there?

KG: After college, I came to Chicago to manage money for a prominent fund of funds. The convertible market became less opportunity-rich, so I put our resources into trading convertibles and equity warrants in Japan, which became a focus of the firm back in the early ’90s. One of my great mentors, Frank Meyer, stressed to me that many businesses are cyclical over time and that, being early in my career, I should consider designing a firm built on a robust platform, and a multitude of strategies, rather than just one strategy.

So, in the early ’90s we stretched into convertibles on a global basis, into statistical arbitrage strategies in 1994, and into risk arbitrage in roughly 1994 and 1995. Over the course of time, we’ve probably added a dozen distinct investment strategies to our platform at Citadel.

LHP: How much did you plan the whole evolution of the firm?

KG: I can’t say there was a master plan. But I knew early on that I loved this business. I wanted to build something unique with people who were as excited about the possibilities as I was, and continue to be. I work with incredibly talented and driven colleagues. They have taken Citadel into strategies, areas of the world and businesses that were never in the original game plan. I am grateful and humbled and incredibly excited about what we will do together for years to come.

LHP: Among the trades that you did over your career, is there one that stands out?

KG: I remember an investment in Glaxo, a U.K.-listed pharmaceutical company that issued a yen-denominated convertible bond in the Japanese market; a yen-denominated Tokyo Stock Exchange-listed convertible against a U.K.-listed company. It was exciting to be at the forefront of global finance, and that trade still stands out years later.

LHP: So you’re trading across three continents, and the security was not well understood?

KG: Japanese local investors really didn’t know what to do with this convertible issued by a U.K. pharmaceutical company. And foreigners, who were major owners of Glaxo, weren’t thinking about looking to Japan to identify and source cheap convertible paper.

LHP: Do you think that being the first to understand a security is a typical characteristic of a good trade?

KG: Being the first trade makes for great stories, but it generally doesn’t make for great businesses. Great businesses are defined by being exceptionally good at what you do, day in and day out. It’s finding the sweet spot of where liquidity exists in the marketplace. That is, trading securities that are liquid enough that you can take meaningful positions but where you can still be better than others in understanding what defines and drives value through fundamental research or quantitative analytics.

___________________

1 The rule for optimal option exercise without frictions is due to Merton (1973), and the analogue for convertible bonds is due to Brennan and Schwartz (1977) and Ingersoll (1977). Jensen and Pedersen (2012) show that it can be optimal to convert early due to short sale costs, funding costs, and trading costs.

2 Such liquidity spirals are analyzed theoretically by Brunnermeier and Pedersen (2009) and empirically in the convertible bond market and other markets by Mitchell, Pedersen, and Pulvino (2007) and Mitchell and Pulvino (2012).